Ah-May, her long braid whipping, came into the bar without warning. Nan had been chewing pebbled ice from the cooler. Seeing the waitress’s heavy face screwed up in anger, Nan swallowed the ice. Her throat contracted painfully. The waitress couldn’t still be mad at her over Ah-Jack’s tables. But Ah-May spat out one word: “Pat.”

“What?” Nan didn’t want to hear about Pat. In the month her son had been working at the Duck House, she’d flinched every time someone said his name.

“We caught him giving it to the boss’s daughter in the storage closet.” Ah-May brightened at the opportunity to share gossip. “Right over the hoisin barrels.”

“Oh my God,” Nan said, realizing that she wasn’t wearing her shoes. She quickly slipped them back on, and the extra two inches she gained over Ah-May gave her some comfort. “Are you sure?”

“Of course I’m sure. I saw him with his pants around his ankles.”

“Oh my God,” Nan said again. “Where is he?”

“Out on the loading dock,” Ah-May said. “That little cunt told me to fuck off when he saw me, as if I were the dirty one!”

“Don’t call my son a cunt.” Nan was heading into the kitchen. The waiters gave her a wide berth, their eyes on the floor. Some of them had known Pat since he was a baby, yet the corners of their mouths struggled to stay flat.

“You don’t tell me what to say!” Ah-May yelled, though from the sound of it, she’d stayed behind at the bar. “It’s not my fault you’re his mother!”

Nan nearly slipped when she stepped into the kitchen. She kept forgetting that her shoes were no longer nonskid, and her arms wheeled for a second before a passing prep cook set her right.

“Okay, Mami?” he said, grinning up at her. She flushed with shame. This tiny man with the gold front tooth had no doubt seen her son hunched over the hoisin barrels.

Sometimes, he never answered at all, blinking into the middle distance, his eyelids erasing her words.

She kept her head low on her way through the kitchen, which was in the middle of cleanup. A pair of dishwashers swept past her with their push brooms. She ignored the warnings from the amigos sitting with their feet propped up on stools. A wave of warm, dirty water washed over her shoes, drenching the hems of her pants. The smell of bleach rose up through the air, but by then she was shoving past the thick plastic curtain, out onto the loading dock. The August night was muggy, reminiscent of the swamps that had once rested over the town. The wet, weighted air was the opposite of what Nan wanted to feel on her skin as she faced her son, smoking with two other busboys. From the grease of the Duck House to yet more oil outside. A strong odor of garbage drifted from the overflowing dumpster nearby.

The busboys — the youngest ones, William and Filipe — flicked their cigarettes when they saw her and went back indoors, jostling each other with their elbows. Pat also dropped his cigarette, but instead of grinding the butt beneath his foot, he watched the ember glint and smoke. He was avoiding her eyes. He was at least a little ashamed. She was humiliated by her relief.

“What am I going to do?” she said in Chinese, which was the better language to scold in. “Every time I think you can’t embarrass me more, you prove me wrong.”

Pat’s face, so quick and bright as a child, had recently turned putty-like and awkward. His features were struggling to grow into his widening skull. He was still handsome, but his brow was heavier, making him look mean. His mouth sometimes had trouble staying closed. Outside stimuli seemed to enter his head at a slower pace, and he often took a few extra seconds to respond to questions. Sometimes, he never answered at all, blinking into the middle distance, his eyelids erasing her words.

“I was bored,” he finally said. His eyes went over her head, as if he were trying to watch a TV show and she was in the way.

“You’re a disgrace! Even your excuses are disgraceful. And what’s worse, you’ve dragged Annie down with you. After her uncle was so generous, giving you this job. No one is ever going to want to help you again.”

“Fine.” Pat balled up his fists and stuck them in his pockets. He was wearing his rip-away track pants, and Nan saw that he had clasped the buttons wrong in his rush to get dressed. She was nauseated by how easily she could read him, how the smallest details could tell her his mood, his preferences, his misdeeds. Yet she hadn’t been able to stop him from unraveling his life.

“Oh, fine,” she said, nearly laughing. “It’s fine if you humiliate your family. It’s fine if you get fired. Then you can do what you want. You can drink and smoke and sleep with girls and set garbage cans on fire! You can waste your life and get yourself killed.”

“Yeah, you’d like that,” he said.

Nan’s mouth went sour. Pat liked to egg her on to get her to drop the argument and leave him alone. But tonight she was more than tired. Her pants were stuck to her ankles, her feet swollen and sore. Everything she usually did, every attempt to help and protect, had backfired.

“I know you think I wish you were never born,” she said. “But you’re wrong. I wish you were never born to me. Then maybe you’d have a mother who didn’t have to work six days a week to keep you fed.”

“Wow.” Pat’s laugh was a sharp, sarcastic sound. “That’s awesome. Go ahead, then. Find me my new family.”

He walked toward the kitchen; she blocked his path. His head loomed over hers. She tried not to be afraid and forced her face up to meet his eyes.

“I thought we could start over,” she said, her voice shy. “You could work in the restaurant with me, and it would be like spending time together, the only way I can. You’re my son, and I never want to hurt you or make you feel unwanted, but I have a job.”

“I hate this place,” he said, but he was running out of steam. “It’s yours.”

Nan wanted to reach up and smooth the furrows on Pat’s forehead, to delight in how her son’s tallness forced her to stretch her arm, but she couldn’t remember the last time she’d touched him. She’d lost the ability, the right, to comfort him. To remind him that he was hers with a stroke of her hand.

“You’re the only thing that’s mine,” she said, her voice straining from tenderness.

Pat took two steps back.

“I don’t want you,” he said. Without a drop of venom in his voice to make his statement untrue. He sounded surprised that he had to remind her of this reality. Nan reached up and slapped his left cheek. Under her hand, his skin was baby-soft, edged with hard stubble.

“Nan!” someone called out, as her hand returned to her side.

She jerked her head. Behind her, Ah-Jack’s face poked out from the plastic curtain. His expression reminded her fingers of the violence they’d done.

Nan’s heart seized so painfully that she thought she might choke. She wished she were strong enough to look back at Pat, to take in whatever hatred or disgust or hurt flashed through that thick, mudlike skin. But she could not bear to.

With her eyes fixed on the floor, she watched Pat’s feet, narrow and long, walk away with surprising lightness. Beneath her, the metal dock shifted and popped. The most sensitive spot inside her, vulnerable and open only to her touch, began to pulse. She pressed against it now. She was no good; she was no good.

Eager to get out of the restaurant, but without a ride until eleven-thirty, Pat ended up standing by the entrance. He could see into the lobby, its brightness making him feel emptier inside. Smoking a new cigarette, he grabbed the door out of exiting customers’ hands.

“Have a good night,” he said each time, bowing sarcastically. Sweat trickled into his eyes when he strained to look up from his bent position. The summer heat was oppressive even at ten at night, like an oven that had only recently been turned off. He gripped the metal duck head welded to the door handle until his hand grew slippery. He wished he could break its golden neck.

He couldn’t count the number of times his mother had been talking to him about tedious but private matters and Jack had inserted himself into the discussion.

He wasn’t angry that his mother had hit him. He knew he’d pushed her too far, and besides, she’d barely grazed him. No, he was angry because his uncle Jack had stuck his nose into their family’s business again. Jack was always intruding, interrupting, disturbing, and never apologizing. He burst from one private conversation to another, like a bull stampeding through a house of locked rooms. It was strange because up until Pat had gotten expelled and had to work this shitty job, he’d loved Uncle Jack. He was fun and loud, and he could joke around with Pat in a way that reminded him of his father but nicer. Back when Jack was gambling, he sometimes let Pat pick his horses, and if they won, he’d peel a few twenties off his bundle of tips, slip them into Pat’s hand, and call it a “finder’s fee, don’t tell your ma.” When Jack came into their house, which was always dark because Pat didn’t think to turn on the lights and his mother was too tired to, he flipped on every switch he passed, until they were all blinking like bats, happy simply because Jack had arrived.

Then, last month, Pat had been forced into this dishwasher gig, and suddenly, even though nothing had changed, not his mother’s behavior, and certainly not Uncle Jack’s, Pat found himself getting angry every time he saw the two of them together. He felt as if he weren’t allowed to join them in their huddles, that he was the intruder during their commute to work. He couldn’t count the number of times his mother had been talking to him about tedious but private matters and Jack had inserted himself into the discussion, taking it deliberately off the rails until Pat grew so frustrated that he had to leave, the sound of his mother’s laughter trailing him. He started to wish that his mother found Jack a nuisance too and not, as she did, a welcome distraction.

Pat knew, even as he stewed by the front door, that there was little chance he and his mother would have done anything but stand in painful silence if Jack hadn’t interrupted; still, he blamed Jack for showing up and ending whatever else might have happened. Pat raged at the older man in his head, calling him pathetic, desperate, lonely, sad, and tried to ignore what he was truly upset about, which wasn’t the interruption exactly but the moment of interruption. If only Jack had been a second later. Stepping through the plastic curtains right when he had, Jack had inadvertently glimpsed the jolt of mortification on Pat’s face, a sensation too physical to hide. And even if Jack hadn’t recognized it, he was still a witness. Pat couldn’t stomach this. Why else had his own mother looked away? Why had May known to shield her eyes as soon as she opened the door to the closet and found him with Annie? Even May understood the violation of staring straight at a person exposed.

Pat had thought it was embarrassing when May had caught him and Annie, but after all the chaos and shouting, when May finally slammed the door shut and left the two of them alone, they had stared at each other for a second before collapsing into silent laughter. In the closet, the embarrassment had been fleeting, a stopgap, holding a place open in his body for the exhilaration, hilarity, and pride that flooded in seconds later. What he felt now was not so easily displaced. With every door Pat opened, with every group of customers bidden goodbye, his humiliation grew pricklier, until it had its own kind of heat.

He wished his mother hadn’t taken his phone away, or his Zippo. He had nothing to play with until it was time for him to meet up with Annie. A group of kids were sharing a joint in front of the convenience store. He could smell the skunky smoke from across the street.

They were complaining about the restaurant, making fun of Jimmy and his tight Italian suits, when Annie cracked a joke about how every day at a Chinese restaurant was bring-your-kid-to-work day.

He began to fidget more. He was pretty sure that he liked Annie too much. They’d only been hanging out for a few weeks. How much did he even know about her? Just that she never said what she was thinking, because what she was thinking was usually too mean. The kind of mean that made him laugh. Inappropriate, exaggerated. Unapologetic. The first time he’d thought of her as more than just a shimmering mirage was the morning she’d walked in wearing an awesomely short skirt, and May had made a loud comment about the length of it.

“It’s ninety degrees out,” Annie had said, and then, when she thought no one was listening, “Saggy-pussy bitch.”

Pat’s laugh was so surprised it came out of his nose, a painful snort that made Annie look over. Seeing she’d been caught, she tucked her hair behind her ear and smiled.

Annie was the first person he’d met who understood what it was like to be in a restaurant family. He wasn’t sure at first, because she wasn’t a waiter’s kid. But she’d said something one day that stopped his heart faster than the first time they’d kissed. He’d been loitering by her stand on his break. They were complaining about the restaurant, making fun of Jimmy and his tight Italian suits, when Annie cracked a joke about how every day at a Chinese restaurant was bring-your-kid-to-work day.

“It’s so fucked up,” Pat said.

“Like the seven dwarfs.” Annie laughed. “Hi ho, hi ho.”

“My mom is so happy I’m here. She only knows how to talk about work.” The last comment fell clumsily out of his mouth. He couldn’t believe how girlish he sounded. He was about to slink back to the kitchen when Annie murmured in agreement.

“My dad’s the same,” she said. “They’re so different in the restaurant, aren’t they? They’re not your parents anymore.”

“I hate the way she sounds.” Pat didn’t know what he was trying to say. He couldn’t find the words and he started to flush. “In the car with Jack, she’s normal, but then we get to work and she’s . . . weird.”

“The waiters aren’t real people on the floor,” Annie said. “More like cartoons.”

Then she poked him in the arm. “You have your mom driving you to work? That’s kind of embarrassing. I can drive you. I need the gas money.”

He’d tried to pretend it was the endless possibilities of those daily car rides that had taken his breath away.

“That’d be cool,” he’d managed to say.

Too embarrassed to keep thinking about Annie, Pat had only the heavy glass door to occupy him. Fewer people left the restaurant; to pass the time, he swung the door open and closed, at varying forces and speeds. The dingy strip mall down the road dimmed and emptied. The convenience-store kids got onto their bikes, shouting and swerving into one another until they were out of sight.

At eleven, dinner service officially ended. When a black BMW drove up, Pat peered into the restaurant’s hallway to find its owner. Instead, the passenger door clicked open and a familiar-looking guy peeled out. The careful way he held his body reminded Pat of the old dudes who did tai chi in the park, but this guy looked younger than Uncle Jack and even, in the dim light, Pat’s mother. The guy’s hair was black but thinning, the sparse strands gelled together to keep his scalp covered. His teeth were big and yellowed. Up close, he smelled exactly the way Pat thought he should smell, of hair ointment, stale tobacco, and shoe leather. The familiarity encasing this guy was spooky.

“The restaurant’s closed,” Pat said. “But can I help you?”

“Has Jimmy gone?” the guy said, his English a pleasant surprise.

“Yep,” Pat said. “Come back tomorrow.”

The guy shook his sleeve back and studied his watch, which glinted in the lamplight.

“In that case, I’d like to bum a cigarette,” he said. When he reached out to take a Marlboro out of Pat’s pack, Pat noticed the missing ring finger and the answer flipped open in his head.

“Sure, Mr. Pang,” he said. The waiters had been clucking over the man’s arrival all evening. Pat had heard, in the silences gapping the waiters’ conversations, the power this “VIP” held over the restaurant. Even his mother had seemed cowed by Pang’s name.

“Call me Uncle Pang,” he said. “How are you tonight, Pat?”

“Fine.”

“You’re the new dishwasher, aren’t you?” Pang leaned in for Pat to light his cigarette. “I’ve heard you’re a handful for your mother, but from what I can see, you’re just a little bored. That’s never good for a young kid like you. For anyone, really.”

“It sucks,” Pat said, eager to commiserate. “This town too.”

“So why don’t you get out now? You’re done with school, aren’t you?”

“School’s done with me.” Pat laughed at his own joke. Pang waited for him to finish.

“That’s right.” Pang exhaled smoke out of his nostrils. “You’re the one who set the garbage-can fire.”

Pat ashed his cigarette a little too hard, nearly spinning it out of his fingers.

“Your mother told everyone you were kicked out for skipping too many classes.” Pang watched Pat scrape the spindly leaves off a weed with the toe of his shoe. “I can’t believe the waiters bought that story. They didn’t stop talking for weeks.”

“All those waiters do is talk shit. Complain and bitch.”

“A caged animal forgets how to be an animal,” Pang agreed.

“Yeah, whatever,” Pat said. “They talk about money most. Depressing.”

“You wouldn’t be tempted by easy money?” Pang’s crinkled eyes

lighted across Pat’s face, scrutinizing him. “You would say no to a thousand dollars in one night?”

Pat glanced back inside the restaurant. “They’re not making a thousand. More like three hundred.”

“I’m not talking about them.”

“A thousand?” Pat sucked on his cigarette. “No way. That’s not enough.”

“So you’re not a slave to money. Just a slave to some money.”

“Shit, I don’t know.”

“There’s a better version of everything,” Pang said. “If you can afford it."

Pang peered at him through eyes half closed with humor. “Put your hackles down. You’ll die young if you can’t laugh at an old man teasing you.” He coughed and looked at the lit end of his cigarette. He flicked away the hot ash and drew out a small case from his jacket. “Stop smoking that crap. Try one of mine.”

Pat took one of the proffered cigarettes, which were wrapped in mahogany-colored paper with golden characters stenciled on the side. The tobacco smelled sweet. Inhaling as Pang lit the end, Pat tasted cherries in the smooth cloud of smoke that coursed into his mouth.

“There’s a better version of everything,” Pang said. “If you can afford it. Here, have the rest.” He tossed not just the cigarettes but also the case that held them. Pat nearly fumbled the catch. At the intersection, a car pulled up, tripping the motion sensor on the stoplight. The light blinked green, yellow, red.

“Thanks.” Pat fiddled with the latch on the antique cigarette case. It looked like real silver. He slipped it into his pocket in case Pang changed his mind.

“You look like you appreciate nice things,” Pang said. “How much do you make a night? Seventy? Eighty?”

“Fifty.” Most of which went to his mom for safekeeping. He barely had enough to take Annie out to the movies.

“Slave labor,” Pang said. “Sounds like you need a better job.”

“Can’t quit.” The suggestion in Pang’s voice made Pat edgy.

“Can’t?” Pang tugged on his earlobe, as if he hadn’t heard correctly. “You got a family to feed?”

The back of Pat’s neck flushed. “Community service,” he said.

A part of him was relieved to have an excuse to close the door on whatever Pang had in mind. The guy seemed slimy. Not that dishwashing was his dream gig. Pat scratched at the collar of his shirt. He could feel the soap scum on his hands. The smell of bleach and sweat hovered around him.

“I worked that out with the judge,” Pang said. “And I can work out something new for you too.” He caught the expression on Pat’s face. “It was my job to keep this place safe. To watch out for the people who work here.”

Pat dragged in more of that heavy, cherry smoke. He glanced again at what Pang was wearing. He couldn’t tell if the suit was expensive, if the watch was designer. Not even if the dude’s shiny shoes were actual alligator skin. These cigarettes—they were the real deal. But everything else?

Pat scratched under his armpit. He was suddenly tired of smoking this fruity thing. He tried to come up with a reason to go inside the restaurant. “So you’re basically the godfather,” he said.

Pang flicked his cigarette expertly at Pat’s chest, singeing his shirt.

“What the hell!” Pat sprang away and brushed at his chest. His shout sounded like a yelp in the empty night. No one was in the lobby anymore. He saw Pang’s hand go into his jacket, and the first thought that jumped into Pat’s head was that he was going to pull out a gun. Instead, his hand came back pinching the corner of a bulging envelope.

“What do you know,” Pang said. “I guess I am.”

“I thought you were looking for Jimmy.” Pat dropped his cigarette and edged toward the door.

“Jimmy’s not here.” Pang pulled the envelope out further. “I’m not going to waste a trip. I have other tasks to complete that have nothing to do with him.”

Pat looked around. The parking lot was nearly empty; only the convenience store across the street was still open. He glanced back at the envelope.

“It was my job to keep this place safe. To watch out for the people who work here.”

“Ten thousand dollars.” Pang flicked the flap open. The yellow lamplight caught the green ridges. This was more money than Pat could make in a year. Much more than his mother made in two months. His heart rebounded against his chest with the anticipation of the cash. With ten thousand, he could move out of her house. He could get Annie something nice, like an emerald necklace. He could buy the vintage Nikes he’d been eyeing on eBay, and a Kawasaki motocross bike.

Pang tucked the envelope into its hiding place.

“You should see the look on your face.” His teasing had a jagged edge to it. “I didn’t realize I was dealing with a kid.”

No one had treated Pat like a little boy in years. He flexed his back muscles. It would take nothing to push this old guy down. But Pang had the upper hand.

“Let me see the envelope,” Pat said.

“Aren’t you interested in what you’ll be doing?” Pang asked.

“I figured you’d tell me sooner or later.”

A laugh rumbled through Pang’s throat like a warning. “Get in the car. We’ll take a ride around the block. Iron out the specifics.” He opened the backseat door of the BMW.

With the money no longer in sight, doubt crept into Pat’s head again.

“I have to get back to work,” he said. “Thanks for the cigarettes.”

“I’ll give you a thousand extra, to keep now, if you get in,” Pang said, reaching across the front seat toward his driver. A thick roll of bills appeared in his grasp.

“Just around the block?” Pat said.

“You’re scared.” Pang looked over Pat’s head, at the restaurant, a bored expression flattening his face. He dug a thumbnail between his bottom front teeth. “I’ve got no time for that. Go inside. Find Filipe or William. Tell them Uncle Pang has an offer.” He handed Pat the small bundle of money and squeezed his shoulder gently. “Here’s a small tip for you. For keeping me company.”

Pat shoved the cash into his pants pocket and ducked his head. He climbed into the car, the air-conditioning a shock to his skin. He’d meant to push past the old guy. But Pang had already stepped aside. ●

Illustrations by Mark Wang for BuzzFeed News.

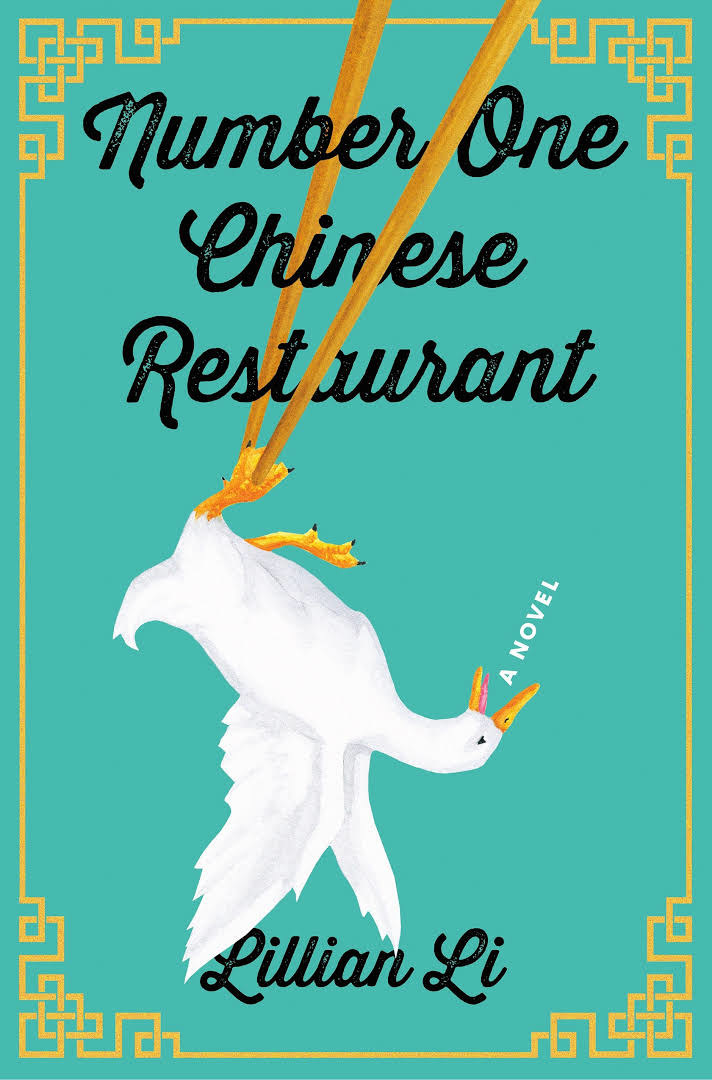

Excerpted from NUMBER ONE CHINESE RESTAURANT by Lillian Li. Published by Henry Holt and Company in the US, and ONE (an imprint of Pushkin Press) in the UK. Copyright © 2018 by Lillian Li. All rights reserved.

Lillian Li is the author of the novel Number One Chinese Restaurant, out from Henry Holt on June 19. Her work has been published in Guernica, Granta, Glimmer Train, Bon Appetit, and Jezebel. Originally from the D.C. metro area, she lives in Ann Arbor.