Uber users who sign up for the app and agree to its terms of service have been given sufficient notice that they have given up their right to sue the company, Uber said in a Massachusetts appeals court Monday.

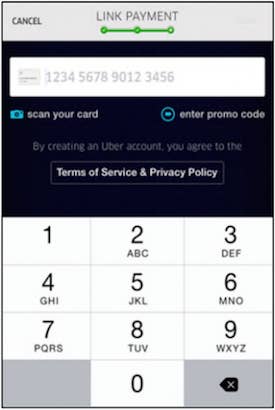

A group of Massachusetts riders who sued the company for charging them an $8.75 airport ride fee, were "expressly and conspicuously informed" of Uber's terms and conditions once they clicked the "done" button to enter their payment information, Uber said. Those terms include giving up the right to bring a class-action lawsuit against the company and an agreement to settle disputes out of court, it said.

"Reasonably communicated notice of terms, coupled with an opportunity to review those terms via hyperlink, satisfies the Massachusetts inquiry notice standard," the company argued. Whether the rider "bothers to access and read those terms is irrelevant."

A screenshot of Uber's notification to consumers of its terms of service and privacy policy.

Last year a district court upheld Uber's arbitration clause in a decision, but the Boston users are appealing that ruling, claiming Uber attempts to "obscure" its terms, which "abrogate basic legal rights," including your constitutional right to a jury trial and any obligation to provide a safe

vehicle, or a safe driver.

"When Uber wants to notify consumers about surge pricing, it makes sure they know about the price hike and requires that they specifically agree to it," Matthew Wessler, a principal at Gupta Wessler representing the Boston riders, told BuzzFeed News. "But when it comes to requiring the waiver of important constitutional rights, companies are much less likely to provide that kind of clear notice."

Uber declined to comment to BuzzFeed News.

In a number of cases brought by consumers challenging contractual language that prohibits customers from suing, courts have upheld the contract. But a California court on Monday ruled that Uber obscured its terms of service and privacy policy on its sign-up screen, meaning the rider suing the company was not reasonably notified that he was giving up his right to a class-action lawsuit.

Uber is far from alone in using so-called arbitration clauses, which prohibit consumers from taking the company to court. They've become widespread across corporate America.

Companies like Starbucks, In-N-Out and Netflix all have agreements that prohibit class-action lawsuits and push people into private arbitration. A number of credit cards, loan products, and telecommunications companies like AT&T and Verizon also require consumers to agree to an arbitration provision.

In arbitration, instead of going to court, consumers pay fees that can be as much as $1,450 to resolve their complaints in front of an arbitrator in private proceedings, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which released a study of arbitration in 2015. The process is similar to court proceedings, except it is less formal and any award is ultimately decided by the arbitrator, who is not a judge.

Consumers resolved 341 cases through arbitration in 2010 and 2011, but only 32 of those cases ended with an award. The total amount awarded to consumers was $172,433, according to the study.

Following a series of state court decisions, arbitration has grown so common that nearly all consumer contracts contain some type of clause that prohibits class actions and forces people into a private dispute-resolution process.

Colin Marks, a professor at St. Mary's University School of Law, told BuzzFeed News that courts have typically sided with companies when these clauses are challenged.

"It’s always on the consumer," he said. "I don't know if the average Uber user knows what arbitration means, but it assumes you know what it means."

Marks said in this case, Uber met the minimum standard to tell users that they have terms and conditions at some point during the sign-up process. Federal and state law does not require companies to disclose key points in the terms, including whether you're giving up your right to sue.

"It's not whether or not it's a legal requirement as an ethical requirement," Jennifer Bennett, an attorney with the consumer advocacy group Public Justice, told BuzzFeed News. "What companies are doing is sneaking in terms that they know consumers aren’t going to be able to find or know or understand which forces consumers to give up their right to go to court."

View this video on YouTube

Bennett said psychological research shows that people tend to overlook details while they are occupied with completing a particular task.

In one experiment, half of people who were asked to count how many times a basketball was being passed around were so focused on that task that they didn't notice a person walking by in a gorilla costume.

In Uber's case, this could mean if a user is presented with the terms of service as a hyperlink while they are typing in payment information, it is unlikely they will click through to read the terms, she said.

"They keep trying to put the burden on the consumer to go around hunting for terms," Bennett said. "It seems wrong for businesses to do."