Retailers are turning to facial recognition software to identify potential thieves by comparing scanned images of shoppers’ faces against a database of known shoplifters. But as more retail stores consider using the technology, privacy advocates and industry stakeholders are debating how the technology should be regulated and how shoppers should be informed about when their faces are scanned.

“We don’t want to live in a world where government bureaucrats can enter in your name into a database and get a record of where you’ve been and what your financial, political, sexual, and medical associations and activities are,” Jay Stanley, an attorney with ACLU, told BuzzFeed News about the use of facial recognition cameras in retail stores. “And we don’t want a world in which people are being stopped and hassled by authorities because they bear resemblance to some scary character.”

The exact number of retailers using facial recognition cameras in their stores is unclear. But Peter Trepp, the CEO of the facial recognition software company FaceFirst, told BuzzFeed News that “hundreds of [retail] locations, growing to thousands very soon” have been outfitted with the company’s facial recognition software as part of their stores’ overall security systems. FaceFirst declined to share details about its retail clients, citing nondisclosure agreements with the companies.

While companies like Cognitec and Amazon Rekognition offer facial recognition software for border control, login authentication, and photo analysis, Trepp said FaceFirst is the dominant retail vendor for facial recognition camera software. “Retail is not quite half of total business, but it’s getting there,” he said. “If you think about the top 40 or top 80 companies you know, almost all of them are thinking about facial recognition or they’ve all at least looked into it.”

Target is one popular retailer that considered using the tech. The retail giant tested facial recognition software “in a small number of Target stores to understand its ability to help prevent fraud and theft,” according to Jenna Reck, a Target spokesperson. Reck told BuzzFeed News that Target posted signs at the entrance of test stores to inform shoppers about its facial recognition software during the test. She said the test has since concluded and the company does not currently use facial recognition cameras. As of publication time, Target still notes in its online privacy policy that some of its store cameras “may use biometrics, including facial recognition for fraud and theft prevention and security.” The company declined to provide details on when and where it tested the technology, or whether it would try using facial recognition in stores in the future.

Walmart also scrapped a test of facial recognition software in 2015 because it didn’t “have the ROI,” or return on investment, according to Fortune. Walmart told BuzzFeed News it does not currently have plans to roll out the technology in any of its stores, but it filed for a facial recognition patent last year to identify unhappy customers and recently patented a system to listen in on employees’ conversations. (Simply filing for a patent does not necessarily mean the retail chain has plans to actually develop and use the technology in its stores.) The home improvement chain Lowe’s also “decided against using the technology in any way” at its stores four years ago after a three-month test at three stores, a spokesperson for the company told BuzzFeed News.

Dollar General, Gap Inc., Macy’s, Costco, and Walgreens told BuzzFeed News they do not use facial recognition software in their stores. CVS, Best Buy, TJX, and 7-Eleven did not immediately respond to BuzzFeed News’ request for comment.

Shoppers don’t have a say about whether or not the software scans them. That’s because companies are not legally required to get consent from shoppers to collect so-called biometric data like face images, except in Illinois where it has been illegal to collect biometric data without written consent since 2008.

“There is not currently consent for this,” said Trepp. “There are lots of protections in place to make sure that the activities that go on with the technology are centered around protecting the private property and the customers and employees of that business. This is not about tracking unknown people or using that data or marketing that data.”

The motivation for retailers to use facial recognition tech is to reduce theft, said Trepp. Retailers reported about 1.33% of sales were lost in 2017 to theft by employees, individual shoplifters, or organized retail criminals, which can amount to billions of dollars in lost sales, according to the retail trade association National Retail Foundation.

Trepp said that in some cases, his company’s technology has reduced theft in stores by more than 30%.

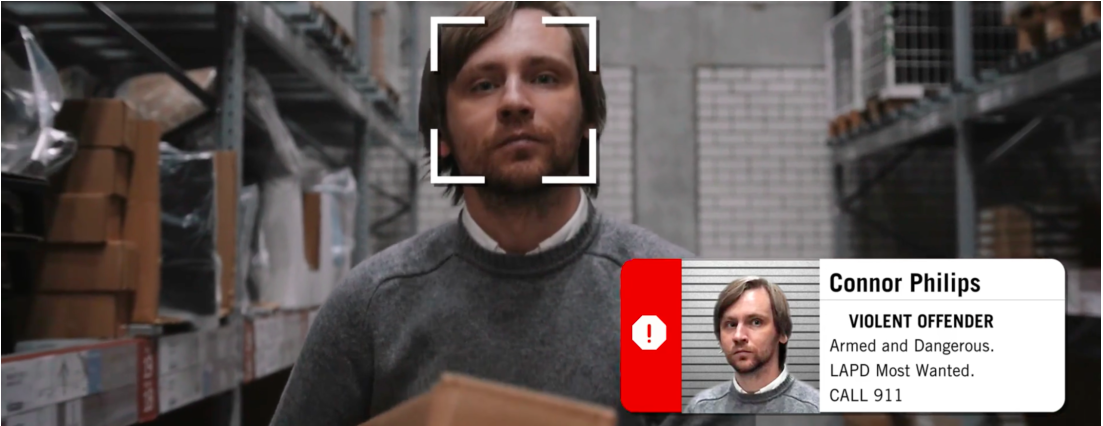

FaceFirst’s software is designed to scan faces as far as 50 to 100 feet away. As people walk through a store entrance, the video camera captures multiple images of each shopper and chooses the clearest one. The software analyzes that image and compares it to a database of “dishonest customers” that the retailer has compiled; if there is a match, the software sends an alert to store employees within seconds of that person walking through the door.

Trepp said the database is not shared with other retailers or with FaceFirst directly. All retailers have their own policies, but Trepp said often stores will offer not to press charges against apprehended shoplifters if they agree to opt into the store’s shoplifter database. The files containing the images and identities of people on “the bad guy list” are encrypted and only accessible to retailers using their own systems, he said.

FaceFirst automatically purges visitor data that does not match information in a criminal database every 14 days, which is the company’s minimum recommendation for auto-purging data. It’s up to the retailer if apprehended shoplifters or people previously on the list can later opt out of the database.

At the heart of the debate between privacy advocates and industry groups over facial recognition tech is the question of whether it should be “opt-in,” meaning people give consent before being targeted by the technology, or “opt-out,” in which people can ask to be removed from any data after being automatically included.

Privacy advocates, attorneys, and recently Microsoft, which also markets its own facial recognition software, have raised concerns over the technology, pointing to issues of consent, racial profiling, and the potential to use images gathered through facial recognition cameras as evidence of criminal guilt. Meanwhile, industry groups argue regulation of the tech stems innovation, pointing to Illinois as an example where Nest’s Cam IQ isn’t sold and Google’s art selfie tool isn’t available because of the state’s biometric law.

“It’s really curtailing innovation,” Carl Szabo, general counsel for NetChoice, an internet trade group that represents companies like Facebook, Google, and Yahoo, told BuzzFeed News. ”It’s making Illinois a technology desert.”

Since laws that would regulate this tech are at a stalemate on a federal level, and demand for facial recognition in retail stores is growing, the ACLU’s Stanley said stores should not use the technology “without at least informing their customers so that their customers can take that into account.”

“Companies seem to be shamefully secretive about the use of it,” he said. “The ultimate fear is that technology is used to track everybody all the time.”