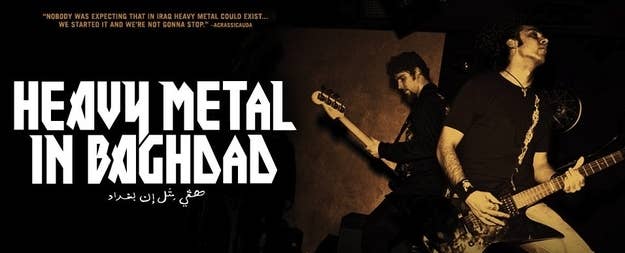

If you're in the mood for a documentary about how badly some people need to rock and roll: Heavy Metal in Baghdad (2007, Suroosh Alvi & Eddy Moretti)

The question is obvious: Why start a metal band in Iraq, of all places? “If you really want to know the attraction, look around you – we are living in a heavy metal world.” So says Faisal Talal, lead singer and rhythm guitarist of Acrassicauda, the subject of the enthralling documentary Heavy Metal in Baghdad. Acrassicauda are very talented, very enthusiastic and going nowhere as frustratingly as possible because of the place in which they live – Baghdad during and after the fall of Saddam. Co-directors Suroosh Alvi and Eddy Moretti drive through the crumbling, chaotic world these guys live in, showing us the hardships they have to endure just to rock out like their guitar heroes in America; a seemingly simple desire — to play music — becomes a lot more complicated when half the band has fled the country and the rehearsal space has been obliterated by a rocket. In this context, a rebel genre like metal can’t help but feel like a political statement even when one band member claims at the outset, “We are not a politic band.”

The hook embodied in the title promises a human interest of story of uplift and triumph in the face of adversity, but that’s not exactly what the directors find. Instead, they find a cycle where one adversity is vanquished only to be replaced by another. When Saddam is in power, they have to include songs that flatter him and headbanging is criminalized because it could be interpreted as Jewish religious rites. When the filmmakers first catch up with the band in 2005, the yen to put on a gig is hampered by unreliable electricity and occasional mortar explosions. Then in 2006, things get too dangerous to even think about rocking. What ultimately emerges is a sober portrait of the cost of war on a civilian populace – a ground-level look at people desperately wanting to and being prevented from doing something we would consider unremarkable, even frivolous. And as the last few moments make clear, abandoning their home city for Syria doesn’t help either. The struggle continues even outside the war zone.

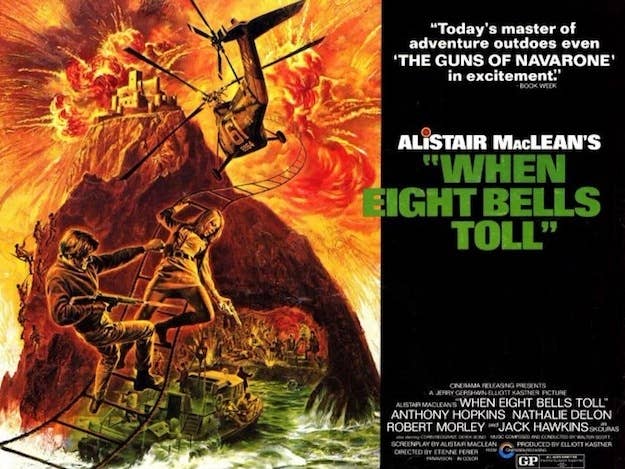

If you're in the mood for solid spy action: When Eight Bells Toll (1971, Etienne Perier)

When a series of films is as successful as the James Bond films, there’s bound to be a number of imitators and Johnny-come-latelys trailing in its wake. But that doesn’t mean that all that follow an established trail instead of blazing a new one are automatically worthless. When Eight Bells Toll, sprung from the pen of Alistair Maclean, is an unusually sturdy and entertaining example of this form. While clearly indebted to the Bond films (right down to the slavish score, which stays just slightly to the left of straight theft), this Scottish-Highlands-set caper – centering around the disappearance of large quantities of gold bullion and Anthony Hopkins’s dogged attempts to uncover the responsible parties and retrieve said gold for queen and country – displays enough personality to set itself apart from the pack.

Part of that is, indeed, in the setting – rather than the typical panoply of romantic locales and colorful villains, When Eight Bells Toll has a small collection of fishing vessels amid the dreary gray fogs of the Scottish seaside. It’s an unexpected setting for such scrappy derring-do, and it goes a long way towards keeping the film grounded in a more realistic vein both witty and gritty. The tone skews less towards outsized heroics and more towards matter-of-fact moves on a chess board – a spy game with as much mental warfare as physical. (“There’s always peril in these waters,” a character remarks to Hopkins early on.) Director Etienne Perier allows the material to unfold organically, concentrating on crisp visuals (some stellar underwater photography in particular), crisper pacing and appropriately droll performances from all involved. Of special note is the interplay between Hopkins, a rugged anti-authoritarian man of action, and his superior, played by the eternally cultured Robert Morley as an old-guard law-and-order fellow with a yen for decorum and distaste for insolence or violence. The two build an appealing odd-couple vibe, with Hopkins trading bemused barbs with Morley (“Too many ifs and buts.” “With all due respect, sir, you haven’t heard an if or a but yet.”) as each tries to find ways to wrap the case up without too much trouble. When Eight Bells Toll allows enough space for wit to creep in, even in places it wouldn’t normally go, and that’s what makes it valuable.

If you're in the mood for a jaw-dropping bit of filth: The Baby (1973, Ted Post)

It doesn’t take very long for Ted Post’s deranged psycho-drama The Baby to reveal that it has a deep, dark sickness welling up inside it — the minute we meet the title character, we know something is amiss. Baby (played by David Mooney in a creepily committed performance) is a fully-grown mentally disabled man who has been kept in a state of faux-infancy by his domineering mother (Ruth Roman) and his two sisters. Apparently, the only person in all the world who sees something wrong with this is Ann (Anjanette Comer), a social worker who has been newly assigned to check up on Baby from time to time. The mind reels – if this is where it starts, how far down the rabbit hole is this thing prepared to go? Brother, you have no idea. When Baby begins an impromptu breastfeeding with a nubile young babysitter is about when a rational person wonders how this ever got a PG rating, and that’s before we get to the cattle prod. Or the belt beatings. Or the incest. Or the drug-fueled birthday party for Baby. Or Ann’s devotion to the case leading her to consider picking up an axe and maybe freeing Baby once and for all.

In its directorial rhythms and central adversarial dynamic between Comer and Roman, the surface level of The Baby behaves strangely like a soapy melodrama, with two fiercely committed women staking a claim to a man and using psychological warfare in an attempt to gradually destroy each other’s lives… except in this case, the man is in diapers and speaks in a series of coos and cries. It’s a Peyton Place plot gone psychotic, traditional structures hiding unspeakable rot and disgust, rendered in astonishingly bad taste. The commitment to following this diseased muse all the way down is bracing and hugely entertaining, but there’s also a larger motive. The perversity works not just as audience-goosing ickiness but also as a magician’s misdirection, a way to keep the viewer off-balance as it rolls inexorably towards its bloody climax. For all the nasty immediacy of the sickness in The Baby, its nastiest and most disorienting wallop is also its sneakiest.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.