If you’re in the mood for a wild and woolly back-and-forth duel: Let the Bullets Fly (2010, Jiang Wen)

The title of Let the Bullets Fly promises non-stop whiz-bang action, but the true meaning is revealed right in the first scene – it’s a statement of serene confidence, of biding one’s time until desired results are achieved. A double meaning presented at the outset sets the stage nicely for Jiang Wen’s period-piece war of wills, where everyone has hidden intentions and dual identities. The meat of the film is the battle for the small hamlet of Goose Town; the wagers of said war are Pocky Zhang (Wen), a notorious outlaw posing as a newly-appointed governor, and Master Huang (Chow Yun-Fat), a tyrannical drug smuggler & human trafficker who rules over Goose Town with a serpent’s smile and an iron fist, with the nervously ingratiating Ma Bangde (Ge You) caught in the middle. That’s the starting position for the principles, and part of the fun of the film is seeing how these identities shift, mutate and get cast off as the game progresses.

And if Let the Bullets Fly is anything first and foremost, it’s fun. Jiang’s style is hyperactive, zooming from scene to scene with breakneck pacing and cartoon logic. The action scenes are cleverly rendered, with Chow and Jiang doing everything they can to stay one step ahead of the other (lots of business involving burlap masks and smuggled bodies abound), and the whole thing is cut to a percussive internal rhythm that makes the film speed along like a rocket even as it’s mostly comprised of people talking out how they’re going to make their next move. It’s immediately obvious why this became the highest-grossing film in China’s history. The contrast between spoken geniality and barely-cloaked unspoken aggression is bracing and appropriate for a film where words and ideas are as deadly as firearms – you wouldn’t think there’d be many ways to wring tension out of someone trying to get the exact meaning of “a pleasant surprise,” and you’d be wrong. Even the political message of the film can be read multiple ways, as a rousing defense of power-to-the-people revolution or as a withering satire of same. We mean what we say, but we don’t always say what we mean. In there, Let the Bullets Fly finds the essence of drama, and does so while also providing a cracking great entertainment.

If you’re in the mood for a bleak study of systemic corruption: The Unjust (2010, Ryoo Seung-wan)

“This will give me leverage until he retires.” This line, uttered by thug-turned-businessman Jang (Yu Hae-jin) upon recording a piece of damning information about beleaguered cop Choi (Hwang Jeong-min), nails the main motivation for every character in the Korean anti-procedural The Unjust: leverage. In Ryoo Seung-wan’s film, nobody is clean and everyone owes something to someone else; thus, everyone is looking for a way to get a leg up on whoever can damage them the most. At the heart of the story is a butting of heads between Choi and strong-willed prosecutor Joo (Ryu Seung-beom) – the two are beholden to opposing interests in a real estate deal (Choi to Jang, Joo to an old-school glad-hander of a businessman who heads the TK Corporation), and this comes back to haunt both of them when Choi gets assigned to wrap up a high-profile child murder case any way he can. Even if it means implicating an innocent man.

The notion of an “innocent man” is an elusive one, though – in a system where everyone is demonstrably corrupt, who’s qualified to judge innocence and guilt? How dirty can one’s hands get in the service of the right before you’re no longer doing right? The line between right and wrong is an idea that fascinates screenwriter Park Hoon-jung (who also wrote the terrifically nasty serial-killer flick I Saw the Devil), and his exploration of this idea in The Unjust is expansive and involving – he sketches the rot of an entire society within the complementary/contrasting portraits of two men doing all they can to ensnare the other before their own sins catch up to them. “If you treat people nicely, soon they’ll walk all over you,” one character says early on. The Unjust suggests there are no nice guys once past actions threaten to unbury themselves.

If you’re in the mood for something with a more historical bent, or if you just prefer swords to guns: The Secret of the Urn (1966, Hideo Gosha)

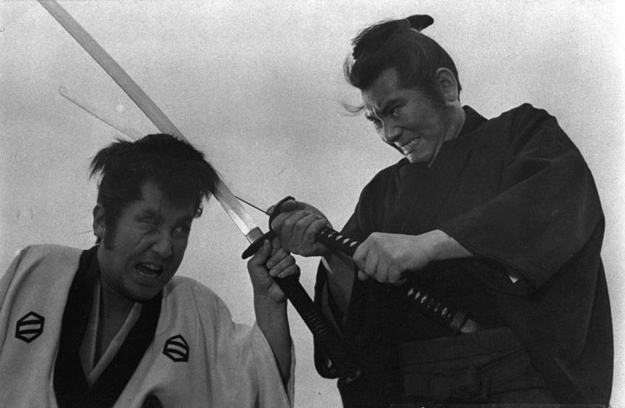

In the samurai world, a man without a clan is a man without allegiances, and a man without allegiances is dangerous. Hideo Gosha’s The Secret of the Urn gives us such a man, sets him loose on a combustible situation and watches the fireworks. Said man is Tange Sazen (Kinnosuke Nakamura); at the story’s outset, he’s a loyal subject who, betrayed by a shogunate spy, loses his right eye and right arm in a fight. While these missing parts would generally constitute a handicap, Sazen seems to turn that into an advantage — his supernatural speed and dexterity are fueled almost entirely by his grinning misanthropic rage. When Sazen comes into possession of an urn whose extraordinary value is crucial to the continued survival of the Yagyu clan, he isn’t keen to give it up, either to the Yagyu representatives, the shogunate forces or the unscrupulous bandits who know how much money it could fetch from the proper parties. Whether his initial hoarding of the urn is a stab at revenge or something else is hard to say; as one ostracized from all factions of samurai life, it’s entirely possible that Sazen (played by Nakamura as a monstrous jester) has grown keen on the urn just to see the havoc that plays out when it disappears.

The story of The Secret of the Urn, with its shifting loyalties and concentration on vengeances for past slights, is standard-issue for the genre (indeed, Sazen is a character who had shown up in several previous films, and Urn is a loose retelling of Sadao Yamanaka’s 1935 film The Pot Worth a Million Ryo). What sets it apart is Gosha’s striking direction. He favors mobile cameras and long takes in filming the battle scenes in service of a unique approach; instead of using these long takes to show everything that’s going down and give a complete portrait of the battlefield, Gosha will locate a focal point (usually the urn or Sazen) and have the camera follow that point as it progresses through the skirmish. This creates a strong, energetic sense of continuity amid chaos and leads to exhilarating sequences like the early battle by the river where the urn is passed from side to side like a particularly slippery football. The Secret of the Urn, sturdy as it is, highlights its director’s ability to vitalize even the most familiar material.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.