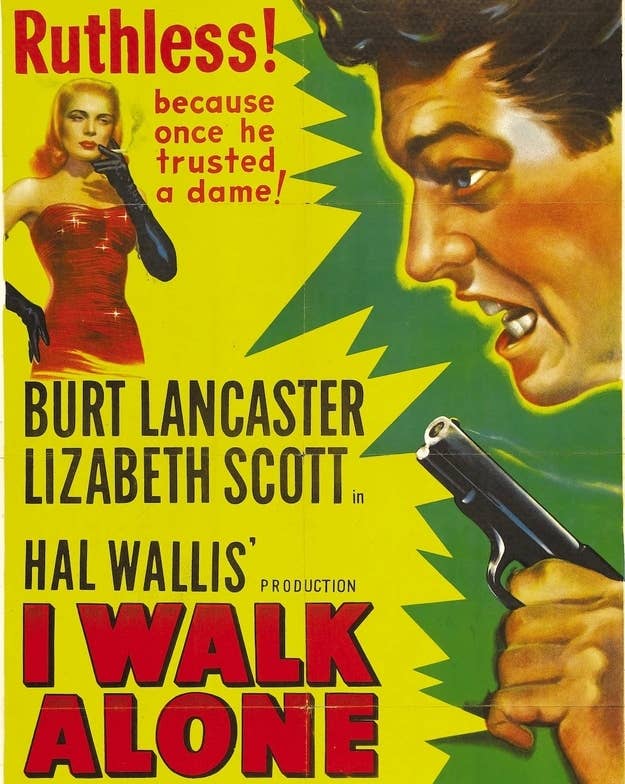

If you're in the mood for a hard-boiled noir with a neat twist and two great stars: I Walk Alone (1948, Byron Haskin)

Even without its unexpected narrative wrinkle, Byron Haskin’s noir tale I Walk Alone would be worthwhile for the peek it offers at the then-dawning talent of its two leads. Burt Lancaster plays Frankie Madison, a former Prohibition bootlegger who at the outset has just been released from a 14-year stint in prison, while Kirk Douglas plays Noll Turner, an unctuous nightclub owner and Madison’s former partner. When Madison gets out of the joint, he immediately comes sniffing around Turner’s territory, figuring he’s been staked in the successful nightclub via a good-faith agreement the two made during the Prohibition years. Things, of course, don’t go that smoothly. The bulk of the film, then, is the friction between the two men (with a jilted nightclub singer played by Kay Lawrence caught in the middle), and the two rising stars make a satisfying study in contrast – Lancaster boiled harder than steel, quick to anger and full of fast-talking bravado, against Douglas, a slimy and deliberate cad with a gambler’s confidence and a salesman’s snaky smile. I Walk Alone was the first time the frequent costars appeared together, and it’s easy to see why the pairing became popular; there’s a striking chemistry between the two men, a sharp give-and-take that sees both excelling but neither dominating.

While its structure and beats are familiar, I Walk Alone has a fairly inspired complication that rears its head about halfway through: Madison, after being stripped of his mistaken belief that Turner would welcome him back as a partner, scrapes together a crew and decides to muscle his way back in, only to find that times have changed and things just ain’t that easy anymore. Without giving too much away, Madison is effectively confused out of any ill intentions by the mutating nature of business; his skill set applies to a way of life long since past, and if he triumphs at the end, it’s only because Turner makes the mistake of trying to best him using those old methods. The noir genre often reflected postwar malaise and paranoia, and in I Walk Alone we have a guy who had to leave his home for a while and finds everything changed when he gets back, a fact he has a lot of trouble adjusting to. There’s a tough post-WWII metaphor if I’ve ever seen one. I Walk Alone isn’t a lost classic (Haskin’s direction is often visually flat, and Lawrence is a weak link), but it’s robust enough to be worth a watch.

If you're in the mood for a sobering drama from overseas: Oslo, August 31st (2011, Joaquim Trier)

The first thing we see recovering drug addict Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie) do in Joaquim Trier’s Oslo, August 31st is fill his pockets with stones and walk into a river. His mental state remains consistent from there. Based on Pierre Drieu La Rochelle’s novel “Le feu follet,” Oslo follows Anders through a day in which he’s allowed to leave the treatment center in which he resides and go back to the city for a job interview. He’s been clean for six months, but as he encounters old friends and family in the course of his day, we see this hasn’t much helped his emotional makeup; floundering in despair and self-loathing, Anders is a wreck, a throbbing raw nerve spitting out accusations and daggers of self-hate in about equal measure. He’s a man drawn towards annihilation chafing against a support system expressly designed to keep him from it, and Lie is very good at embodying the rage and confusion that consume this pained young man. His expressive eyes are key, as is his keen sense of dialogue tone; when he refers to himself as “a spoilt brat who fucked up,” there’s a latent element of pity angling there, but Lie coats it in castigatory disappointment so it feels less like an angsty whine and more like a barrel-bottom hard truth.

Lie climbs expertly into Anders’s skin, but Trier wants us in there too. The idea with Oslo seems to be to get the audience to a place where Anders’s depressive outlook can be understood and felt to a degree, and in this Trier’s empathetic direction is invaluable. Where handheld photography is often used to convey a sense of urgent verisimilitude, here it seems to reflect the unsteady, teetering nature of Anders’s emotions – realism as expressionism. Further, when Trier does go for a stylistic gamble, it tends to pay off beautifully. Especially impressive is a scene where Anders sits in a café and listens to the world around him; as his ears pick out snippets of conversations, it becomes clear that every bit he catches (a recitation of a bucket list here, a oblique discussion of Kurt Cobain there) is feeding back into his own dire outlook, with all other context pared away.

If you're in the mood for a starkly made beauty that rewards the patient: The Turin Horse (2011, Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky)

“Even the embers went out.”“Tomorrow we’ll try again.”

One horse falls, and the world falls with it. Béla Tarr and Ágnes Hranitzky’s severe and beautiful The Turin Horse opens with a recounting of the circumstances that undid the mind of famed philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (upon witnessing a farmer whipping a horse, he threw his arms around the horse’s neck and then collapsed), then transitions to a sparse narrative that functions as the undoing of the world in the incident’s wake. The farmer, an old man named Ohlsdorfer, and his daughter live in a rural country home in a land buffeted by constant fierce winds, and the horse is crucial to their livelihood. But the increasing, Bartleby-style stubbornness of the horse indicates it’s no longer fit or willing to do its job. So the farmer and his daughter go about their daily routines, pantomiming normalcy and hoping the next day will bring a change in fortune. This could be a slog in many hands, especially at two-and-a-half hours. For a lot of people, it still will be. But the careful and immersive detail Tarr and Hranitzky lay out before us, for me, is never less then hypnotic.

It helps that the film is never less than sumptuous. The Turin Horse is shot in high-contrast black and white, with every light and every shadow capturing the well-worn crevices and collected detritus that come with a lifetime of spartan living. Tarr, well-known for long takes, holds true to form here, and within each long shot are a dozen individual shots that could be isolated and framed. (My favorite: a late-film shot where a cart climbs a ridge in the background towards a barren tree while dead leaves whip about furiously in the foreground.)

The pacing is such that every gesture feels significant, and any rupture in the placidity (say, a visit by rowdy gypsies) feels like a violation. Yet, for a movie with so much stillness, there’s precious little silence in The Turin Horse. The maddening howl of the wind blowing around the little house makes the presence of sound constant and unabating, and it becomes a deafening roar whenever the door to the home is opened and the outside world is allowed to intrude. Even when the wind cannot be heard, the funereal score, a piece for organ and piano, drones on. The point is clear: There will be no solace here.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.