The mega-movie The Avengers hits megaplexes today. Since superheroes never die — at least not forever — the theme this week is the antithesis of that, in a way: men dying. So we've got Jeff Bridges in a raw anti-Western, a documentary about the death penalty, and mobsters blown up with a grenade launcher.

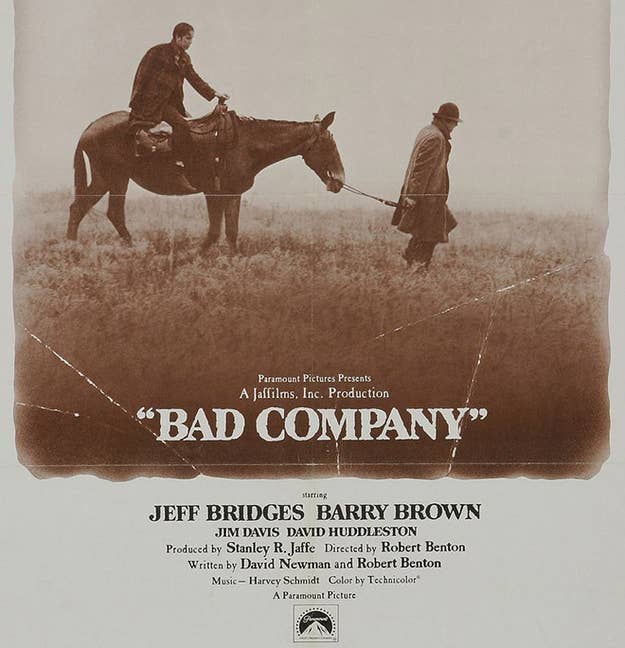

If you're in the mood for Jeff Bridges with a bowler hat and a six-gun: Bad Company (1972, Robert Benton)

"Go West, young man." This imprecation hovers over Robert Benton's low-key anti-Western Bad Company like a sickly ironic joke. Horace Greeley's promised land turns out to be an endless barren expanse, a graveyard of grass and scattered gnarled trees through which mangy gangs of men wander, fighting over scraps of food and money. It's a survival-of-the-fittest situation, and mistakes tend to be very costly. In this world, as apart from the myth of the West as the post-apocalyptic landscape of The Road Warrior, what chance do fresh-faced youngsters like Union draft-dodger Drew Dixon (Barry Brown) and would-be bushwhacker Jake Rumsey (Jeff Bridges) have?

Youthful enthusiasm can only carry one so far before the nasty realities of the world come crashing through, and that's where the potency of Bad Company, one of the finest of the '70s-era revisionist Western, lies. Bridges is enjoyably gregarious, making a fine contrast to Brown's straight-laced rich boy, and he's got just enough piss-and-whiskey bravado in his apple cheeks to understand why he'd attract a following of like-minded young men. His youth, though, proves to be a liability when it comes to putting up or shutting up. As the film inevitably grows grimmer, it becomes a matter of having something to prove, that these boys won't let the West swallow them whole. There's violence and death, but Benton's quiet, deliberate tone takes the shock out of it - when someone dies, it's abrupt and without fanfare. It's simply a way of life. The Vietnam-era parallels are tough to miss, but at heart this is a dark coming-of-age story that treats its darkness as a fact rather than something with which to pummel the audience.

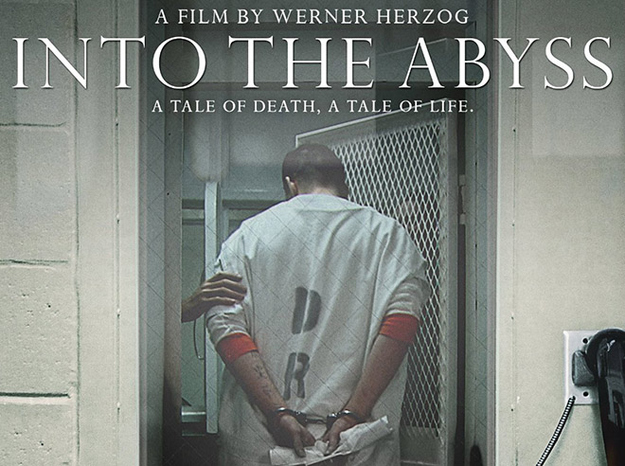

If you're in the mood for a documentary that isn't going to make you feel good: Into the Abyss (2011, Werner Herzog)

Leave it to Werner Herzog to isolate unusual details and conversational side streets even in a somber documentary about capital punishment. A lot of people could have made a film about the triple murder that led to the execution of Michael Perry and the incarceration of Jason Burkett. None of those people, though, would have made Into the Abyss, a serious-minded film that nevertheless opens with a death-house priest talking about a day in which he avoided killing a squirrel with his car and features a conversation with a friend of Burkett that evolves into a discussion of the joys of late-life literacy. Herzog, as always, is fascinated by what marks people as individuals, what I have that you or Herzog or the guy down the street doesn't have. And it's that individuality that makes us irreplaceable, which is why death carries so much pain with it.

Herzog states his position on capital punishment right at the beginning (he, like Captain Spaulding, is against it), yet the film, to its credit, resists becoming a simple polemic. Rather than the blunt tool one would expect from, say, Robert Greenwald, Into the Abyss is after something larger. Using a single case as a focal point from which he can spread outward, Herzog builds a meditation on the reality of death and its aftermath; its traumatic force is seen less as a cessation of life than of time, leaving behind survivors with mental scars never to be erased, cookie dough never to be baked, cars forgotten in impound lots reclaimed by nature and entropy. He highlights other losses in the lives of the principles — one survivor lost a sister in a car accident, while another lost pretty much the entirety of her family within a six-month period (she disconnects her phone because all she gets is bad news). In this manner, it seems that Herzog is opposed to the death penalty not for political reasons but because life is random and cruel and violent enough. We can die at any time, leaving a hole in the world where we were. No need for the state to speed up the work of the cosmos.

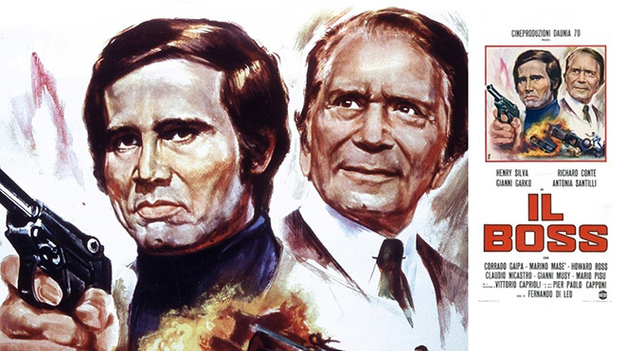

If you're in the mood for guns, boobs and Henry Silva's stone-faced badassery: The Boss (1973, Fernando di Leo)

Italian crime-genre specialist Fernando di Leo's worldview is a cynical one. In his films, there's no loyalty that can't be undermined, no oath that can't be forgotten, no promise that can't be broken. They generally boil down to knotty political gamesmanship in the form of large-scale mob wars, and the victor is whomever reaches the end credits with their pulses intact. As such, The Boss is a solid entry in his resume. It centers around a Sicilian crime family led by Don Corrasco (Richard Conte) that gets embroiled in a conflict with Cocchi, a rival angered after Lanzetta (Henry Silva), one of their assassins, uses a grenade launcher to wipe out an entire room full of porn-watching dons. Corrasco alternately agrees to appease Cocchi or have him wiped out, depending on who he's talking to; meanwhile, Lanzetta tries to balance his fierce loyalty to Corrasco with his familial affection for Corrasco's second-in-command Don D'Aniello, who becomes a liability after his college-age daughter is kidnapped by Cocchi's forces.

You see how quickly the plot becomes a thicket of characters and criss-crossing motivations. Things get much less complicated as the film rolls on, though, mainly because the solution to any conflict is that Henry Silva shoots someone. What this means for you, the viewer, is that there's an assassination or full-on gun battle every ten minutes or so. Plus, there's the small matter of Don D'Aniello's daughter, whose response to her abduction is to sleep with all of her captors — and to Silva's rescue of her by sleeping with him. Betrayals fly as fast as the bullets, bodies drop like shell casings and a terrifically taciturn Silva strides through it all, unflappable and constantly two steps ahead. The story may get a bit dizzying, but let no one say The Boss doesn't deliver on its own cynical promise.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.