Imagine you’re standing at the counter and I’m waiting for you to speak. You open your mouth and out come the words, “Show me something I’ve never seen before.” I think I just might able to help you with that.

If you want to see a film from a country you’ve never seen one from before: Viva Riva! (2011, Djo Munga)

Funny how a change of venue can liven up a stock situation. There’s a lot that’s familiar about Viva Riva! — the loudmouth hustler in over his head, the femme fatale, the dangerously violent antagonist, the ever-shifting loyalties. You know, basic gutter noir stuff: Our lead, Riva, has stolen from some Angolan business associates and while they try to track him down, Riva’s boundless confidence leads him to doggedly pursue slinky redhead Nora (Manie Malone), whom he encounters at a party one night; this unquenchable desire puts him at odds with Nora’s paramour, local gangster Azor (Diplome Amekindra). Much bloodletting and gunfire ensues. The setting, though, is unique — Viva Riva! is set in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Repuplic of the Congo, and that makes the difference. It’s not just a case of slapping a new coat of paint on an old car and thinking that’ll make it run differently; writer/director Djo Munga does a careful job of tying the pulpy plot and its stakes into the reality of the surroundings.

It helps that Riva is a persistent and fairly charming bastard – the kind of guy who’s smart enough to get himself into this situation and to realize after a point that there isn’t a way out of it, yet motivated enough to keep pushing forward anyway. (He’s also the kind of guy who, in an eye-popping scene, can apparently motivate a woman to offer him oral sex through a window frame.) Once the two major threads (the Angolans and the Nora/Azor/Riva triangle) start converging, all that can be done is watch things fall inexorably into place. The bodies and betrayals pile up, the air gets thick with panic and greed and desperation starts to inform every character’s moves. Munga’s energetic direction keeps things lively, and his screenplay gets a lot of mileage out of its sensational sleaze, but the end point is not a lively one. It’s not that kind of story, and the parts of Kinshasa we see are not that kind of environment. Look at that title. See the exclamation point. Is that excitement or defiance there?

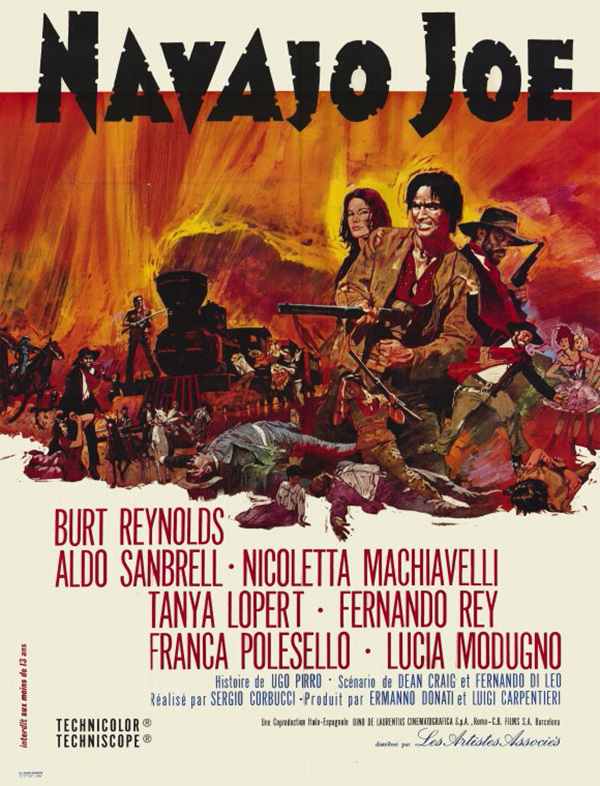

If you like both Burt Reynolds and spaghetti Westerns and wonder what the two combined would be like: Navajo Joe (1966, Sergio Corbucci)

Navajo Joe provides the answer to the age-old question: How many times in life does a man get to see Burt Reynolds as a revenge-minded Navajo Indian? Answer: One. One time. Reynolds notoriously hates this film and for years considered it the worst thing he’d ever done. To which I can only say: If a man is telling me that Navajo Joe is hopeless junk and Cannonball Run 2 is a good time at the movies, I may not trust that man’s opinion. With good reason, too — Navajo Joe is a strong, solidly crafted work by genre specialist Sergio Corbucci, heavy on the dust and despair and senseless, random violence. Right off the bat, Corbucci sets the bloody stage by having villainous scalphunters swoop in and massacre a village of peaceful Indians. They miss Reynolds, though, and he spends the rest of the film methodically exacting his revenge and picking off the marauders one by one, later entering into a pact with a besieged town just so he can knock off the rest of them.

While his tone here isn’t as bleak as his masterful The Great Silence, nor is the violence as all-encompassing as his influential breakthrough Django, Corbucci’s pitiless eye keeps the violence swift and brutal. (The terrific, pounding Ennio Morricone score keeps things propulsive as well.) At times, the focus on Reynolds skulking around and popping up from just out of frame to take down another adversary give this the feel of a proto-slasher movie (though he’s running around the margins and felling bad guys from the story’s start, Navajo Joe isn’t properly introduced as a character until twenty minutes have passed, and half the film is over before we learn his name). Given this bloody-minded stance, the lead role needed to be filled by a man with a magnetic presence, one who could convincingly portray determination and anger with a minimum of dialogue, and Reynolds acquits himself admirably. Even later, when the script opens him up a little, the performance is rooted in the physical, in the glares and grimaces Reynolds shoots out. He may not have had a good time, but he still managed to turn out something of value.

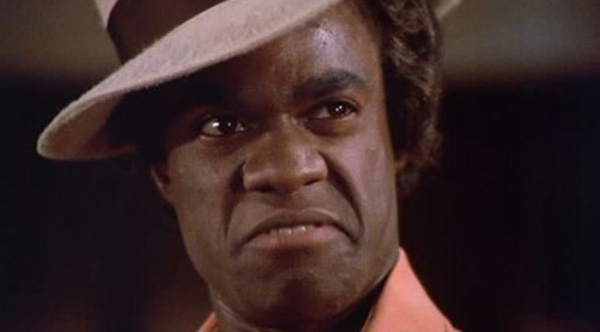

If you just want to simmer in a blaxploitation stew of hypnosis, possession, revenge and ghost pimps: J.D.’s Revenge (1976, Arthur Marks)

What a way to ruin a day: You’re a straight-laced law student who drives a taxi to put himself through college, but one little stunt with a stage hypnotist and suddenly you’re possessed by the vengeful ghost of a murdered pimp.

So it goes for poor Isaac (Glynn Turman), the unfortunate supernatural puppet of the deceased J.D. Walker (David McKnight) in Arthur Marks’ enjoyably nasty J.D.’s Revenge. Thing is, J.D. was shot to death after being wrongly accused of killing his own sister, and he’s still intent on settling that score, whether or not that interferes with Isaac’s plans for his future or his relationship with his increasingly-alarmed girlfriend Christella (Joan Pringle). That’s the thing — J.D. may be innocent of the crime for which he was killed, but he’s not an innocent all around. He’s a mean, mouthy, backhanding son-of-a-bitch — in other words, a pretty typical pimp, and Turman is clearly having a blast with his bipolar portrayal. (Highlight: Isaac-as-J.D. picks up a woman in a bar, lays her, then beats the hell out of her man because he had the audacity to get offended that J.D. just made a cuckold of him.) Subtext abounds here – in particular, there’s a genre autocritique that disdains the sort of pimp-life romanticism that popped up in a lot of places during the ‘70s (and still thrives today), with Isaac’s struggle being mirrored by that of Reverend Elijah Bliss (an electric Louis Gosset Jr.), a former pimp-turned-revival preacher. They’re both fighting the return of the repressed pimp within, as it were, and in doing so working out age-old conundrums of masculinity and identity.

As heavy as all that sounds, the timbre of J.D.’s Revenge is gleeful anarchy — Marks knows how to push his exploitable elements for all they’re worth, and he knows the exact diseased level on which to pitch them. It’s an amalgam of The Possession of Joel Delaney and The Mack, a supremely ridiculous film that nonetheless has enough blood and boobs and swagger to sell itself beautifully. The signature shot is that of J.D.’s murder being intercut with the slaughter of a cow; it’s a tasteless image but also undeniably effective. And for all the unpacking one can do of its gender politics or genre criticisms, J.D.’s Revenge also has a character say in all seriousness, “You’re pimping God’s consciousness like some kind of fat whore!” I don’t know about you, but that’s the sort of shit that gets me unreasonably excited.