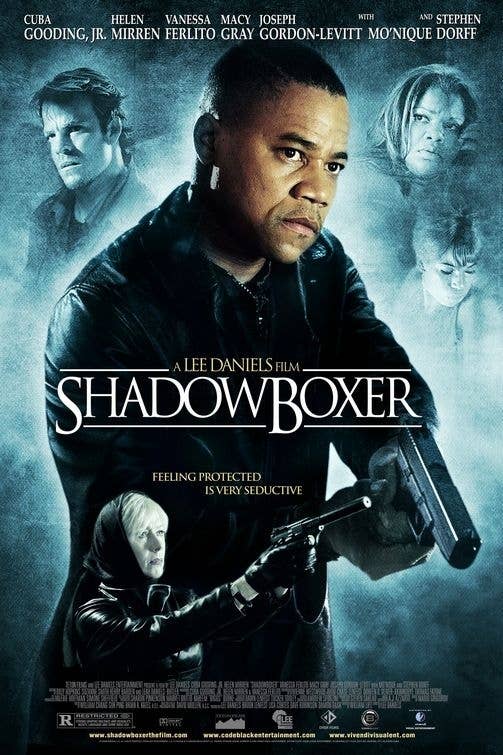

If you're in the mood for a big ball of crazy featuring hitmen, bad sex and Cuba Gooding Jr. in a dress: Shadowboxer (2005, Lee Daniels)

Say what you will about Lee Daniels – he does not make bland films. The director of the Oscar-nominated misery typhoon Precious and this year’s Cannes pick The Paperboy first dipped his toes into the directorial waters with Shadowboxer, and it’s a doozy of a debut. Even mere plot details mark this out as a transmission from Planet What the Hell: How many films can you name that feature, as a male-female hitman team, Cuba Gooding Jr. and Helen Mirren? Wait, they aren’t just business partners – they’re also lovers! Let’s up the ante further – Mirren is also Gooding’s stepmother! And they desperately need to perform the standard-issue one last job (on a pregnant woman, of all people), because she’s dying of brain cancer.

And that’s just scratching the surface – there’s also Stephen Dorff shooting someone while naked, Mirren getting jiggy to a Nas tune, Mo’Nique and Joseph Gordon-Levitt as a seedy couple, Gooding in drag and several heavy-breathing sex scenes that fly in the face of all logic, taste or decency. (The one with Mirren and her red dress is… indelible.) What makes it fascinating, in its thoroughly wrong-headed way, is how straight Daniels plays all of this. The gulf between the fact of the material and the tonal intentions of its makers is vast, yet it’s the unshakeable conviction that gives Shadowboxer its weird charge – I find it far more interesting to see this level of investment in material, even bad material, than in any number of tossed-off unloved mediocrities. This film is pitched at a level of hysteria that can only be achieved by people who aim high and dream big. It’s a fiasco of grand proportions, one where the failure is more or less total, but because of that it’s also unforgettable. You’ll never see another like this one.

If you're in the mood for a bracing shot of Russian bleakness: My Joy (2010, Sergei Loznitsa)

"They say nice people used to live here. Now it's nothing but riff-raff." An old woman bitterly lodges this complaint to no one in particular midway through Sergei Loznitsa's dark My Joy, and in doing so she provides a handy thesis statement. In an assured feature debut, Loznitsa (director of this year's Cannes entry In the Fog) shows us a Russia plagued and informed by a bloody history, filled with conniving opportunists and casual degradation — a country of scavengers.

Initially, Loznitsa's metaphorical history lesson centers around a truck driver who makes a wrong turn going through a checkpoint and the people he encounters on his detour, from a ghostly old war veteran to a teenage prostitute. But the further he drives away from the known, the less important he becomes within the narrative fabric — one of many examples of the individual being swallowed up and beaten down by the collective. There's a fluidity of time at work here, with flashbacks falling in unannounced more than once (context clues keep us oriented), and certain actions and setpieces (e.g. a knock at a farmhouse door, a confrontation with two power-tripping checkpoint cops) get doubled at crucial junctures, usually to dark ends. The point seems to be: History is impossible to escape, and its repetition is inevitable if undesireable. This easily could have devolved into a nihilistic slog, but Loznitsa keeps interest from flagging with a mordant wit (a soldier opining, "A mass grave is a happy grave") and a solid eye for darkly poetic imagery. The first shot of My Joy is from the inside of a cement mixer. The following shot shows a body being dumped in a ditch and buried. From the start, death is in the foundations and structures of Russia.

If you're in the mood for a barbaric-yawp masterwork: The Lovers on the Bridge (1991, Leos Carax)

Love is a universal feeling that lends itself to all manner of gestures, from simple to grandiose. Where most directors would be content with the former, Leos Carax’s The Lovers on the Bridge is an eruption of grandiosity. Carax, whose Holy Motors has shaped up to be one of the highlights of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, takes what could be a plain love story in other hands and spins it into a dizzying maelstrom of images and sounds and emotions, all as big as life.

The opening scene alone, contrasting as it does Dennis Lavant’s drug-addled vagrant grinding his forehead on the asphalt of a darkened boulevard with the revved-engine sports car hurtling towards him (experienced entirely via the hands of the driver and passenger) as an eyepatch-sporting, cat-carrying Juliette Binoche looks on, announces this as a work apart. From that anti-meet-cute, Lovers develops into a tale of l’amour fou between Lavant and Binoche, who’s slowly going blind from an unspecified condition. As deeply and violently as Lavant falls for Binoche, so too is Carax madly in love with the form of cinema; with Lovers on the Bridge, he aims to make the style its substance and he succeeds spectacularly. Unforgettable images abound – Lavant surrounded by posters of Binoche in a subway tunnel, the Samaritaine building lighting up to the crackle of radio static, a cut from Lavant blowing fire to jets firing off plumes of multicolored smoke – with the high point being a Bastille Day celebration on the broken-down Pont-Neuf, fireworks exploding in the background as the two whoop and flail and dance in drunken revelry. (Gotta feel bad for the unsuspecting individuals who went to see this in its brief, Miramax-sponsored US release – the title and poster promise a genteel romance rather than this freewheeling, grimy howl.) Carax’s eye is transfixing, his sensibilities extravagant and his talent enormous. In going for broke with Lovers on the Bridge, he crafted a transfixing, uncompromised masterpiece, confounding and beautiful and brilliant.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.