Puberty is absurd. You’re minding your own business, enjoying your childhood, and then bam: boobs, period, and the sudden, overwhelming knowledge that you’ve become prey in the eyes of countless boys and men. As a woman, you don’t get to own your own body; at least not really.

For me, the boobs seemed cool, at least at first, until all they seemed to do was invite prolonged stares from boys and grown men alike. Some of them would follow me in their cars, shouting at an obviously barely pubescent teenager with braces as I walked home from school. Then there was the boy in grade seven who would snap my bra strap as we moved in the narrow hallway between classes. And the boy in high school who, as I tried to go up the stairs, would jut his arm out so my chest would bump into it, and he’d take a moment of pleasure to stare and feel powerful. The more my body changed, the more I was reminded that its apparent purpose was exploitation.

As for the periods, those weren’t a cakewalk either. My first arrived abruptly at my own 12th birthday sleepover, in what looked like a murderous crime scene in my underwear. A few days later, my mother reminded me I could get pregnant now.

I was angry. I felt less like I was becoming a woman and more that I was becoming a casualty, and no one else seemed to give a fuck. Boys will be boys; periods are normal; fertility is a dangerous but inevitable curse. Nothing about it felt natural. Then I found an imperfect hero who understood the rage bubbling inside me.

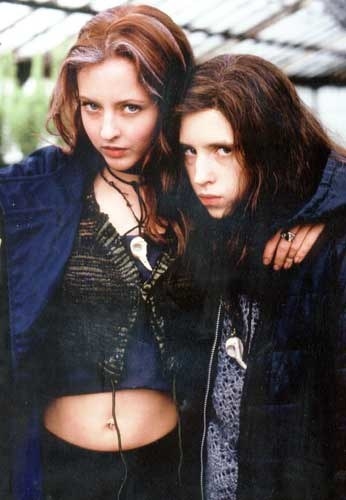

Twenty years ago, in August 2000, Ginger Snaps premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. It’s a horror film with that sort of indescribable made-in-Canada quality that had a $4.5 million budget, a decent chunk of change for a horror flick from the country. The film centers on two sisters — Brigitte Fitzgerald (Emily Perkins) and Ginger Fitzgerald (Katharine Isabelle) — a pair of outcasts in their cookie-cutter suburban town of Bailey Downs. The two have a close bond — like, suicide pact close — but they’re driven apart when Ginger gets her first period, and suddenly womanhood and all its trappings enter the equation. To make matters worse, Ginger then gets bitten by a werewolf, unleashing a more monstrous kind of puberty that transforms her into a creature brimming with confidence but also a hunger for sex and flesh.

I felt less like I was becoming a woman and more that I was becoming a casualty.

The reviews for Ginger Snaps after its debut were generally positive, with the New York Times lauding director John Fawcett as “fundamentally a sly, dry satirist.” In the years since, the movie and its two sequels have become cult favorites for anyone seeking horror with a feminist bent.

I watched the film a few years after its release, when I was 16, and I was immediately hooked.

“I can’t think of any of other film that is equivalent to [Ginger Snaps],” Paula M. Uruburu, a film professor at Hofstra University, told me.

Uruburu explained that, generally speaking, women have not been treated well in horror. They get to be victims — scream queens and rape survivors — or they’re the final girls who only make it to the end because they were chaste enough to deserve it. Ginger blew that all up.

“She becomes empowered and she takes control of everything, and I think that’s one of the reasons why so many young women like it,” she said. And in the grand tradition of werewolves, Ginger gets to be both Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf.

“It’s a very underrated film,” she said. “It’s a miracle it got made at all.”

The movie opens on Brigitte and Ginger in their drab basement bedroom, Ginger delicately teasing her wrist with a chef’s knife. Then there’s a montage of the two in a morbid series of photos staging various self-inflicted deaths — Brigitte swinging from a noose, Ginger with fake intestines spilling out from her stomach beneath a lawnmower. All for a school project, which their teacher finds wholly disturbing. To my teen goth sensibilities, this was good shit.

I wasn’t a horror fan. I’m still not, really, but I was nonetheless drawn in by one thing in this movie in particular: Ginger. She was designed that way, to be fair. Of the sisters, she’s more outgoing, more beautiful. But it wasn’t just that. As she transformed into a werewolf, she transformed into an antihero I could get behind.

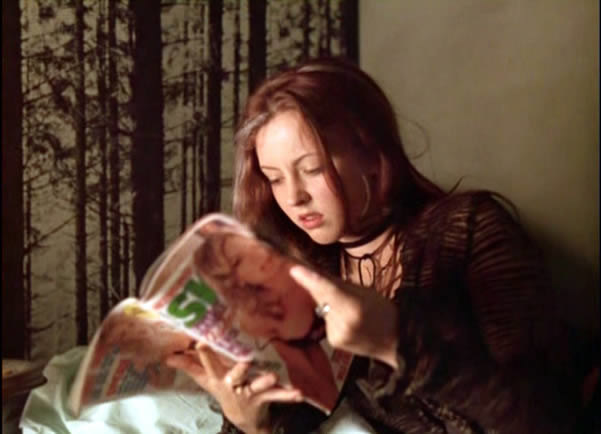

The transformation itself is a very in-your-face metaphor for female puberty. As Ginger’s bite infection takes over, her period is literally dripping out of her, pooling between her feet. She grows hair in weird places. She suddenly sees the appeal in sex. With my own body changing in new and weird ways (even weirder thanks to a polycystic ovarian syndrome diagnosis), this was an entirely welcome plotline.

To my teen goth sensibilities, this was good shit.

While reviews from the time take note of the lycanthropy-as-puberty theme, they don’t dive into the genius subtly imbued by the film’s writer, Karen Walton. As Ginger tries to get help, she’s assured over and over that this is all perfectly normal. In one scene, the bubbly school nurse gestures to a female anatomy poster and gives the usual spiel about uterine lining before handing both girls a condom. Meanwhile, Ginger is spouting thick gray hair. It’s a clever statement on how we downplay or flat-out ignore “female troubles,” no matter how much pain and grief they cause.

My own body at the time was undergoing a similar transformation. I mean, I didn’t grow a tail or anything, but my periods ranged from disappearing for months at a time to being a tsunami of blood and tissue for weeks on end with cramps that made me double over from pain and nausea. Meanwhile, my face had bloomed a patch of thick, dark hair that was slowly making its way down my cheek, mortifying me. It turned out these were all very run-of-the-mill PCOS symptoms, but I suffered in quiet because I was convinced there was nothing to be done about it. This was just being a woman. This was just the curse of it all. Thankfully, a woman doctor later recognized my symptoms and got me to a specialist, but for most of my high school years, I just felt like a freak.

That’s where my anger kicked in. Ginger understood that, too. Her werewolf bite caused a sexual awakening, making her see boys differently, but her lust was complex, too. The boy she ends up pursuing is Jason, a walking stereotype of gross male adolescence who sits on the bleachers during Ginger and Brigitte’s gym class with his buddies yelling about their bouncing breasts. As Ginger blossoms, he picks her, too, but as a conquest, a target, a piece of prey. Ginger, though, turns his preying right back on him.

One night, Ginger and Jason are making out in the back of his car, Ginger’s new animalistic tendencies finally finding an outlet. She’s the aggressor, climbing on top of him like something to be devoured — and he doesn’t like it.

“Just lie back and relax,” he tells her, clearly used to being in charge.

“You lie back and relax,” she snaps back.

“Hey, who’s the guy here?” he says, before she pushes him down and takes what she wants.

But hey, this is a horror movie, after all, and after screwing Jason, she ends up devouring a neighbor’s dog — which leads us to the most important line of the whole movie.

“I get this ache, and I thought it was for sex,” she tells Brigitte, “but it was to tear everything to fucking pieces.”

"That frustration, that rage is about reckoning with who you are in the world if you've been born into it as a woman.”

If I wasn’t already in love with Ginger, hearing that line sealed the deal. Ginger’s whole story isn’t just about puberty or sex; it’s about the inherent rage of womanhood, a rage all too rarely explored on screen in such an aggressively bloody manner. Ginger felt that rage, and she bit back.

I reached out to the movie’s writer, Karen Walton, to discuss the film’s legacy. The movie itself was a collaboration between Walton and director John Fawcett, who initially reached out to Walton hoping she’d write a script that put a twist on the classic werewolf trope where the transformation tells the story of male animalistic tendencies. That’s how she created Ginger.

“She is funny. She's super smart. She's super cool. And for me at the time, she had a problem with all the right things. Do you know what I mean? Like what she was spoiling to rebel against, or was well on her way to rejecting, was an idea of who you were supposed to be at 15,” said Walton.

Her goal was to flip the typical script of how women are portrayed in horror. It’s sadly notable that none of the girls in Ginger Snaps are raped or otherwise sexually harmed.

“Not only was that not the tone of the movie I was writing, it actually didn't make sense in the arc of where Ginger was going,” said Walton. “Yes, she was losing control to something else taking over, but she never stopped being who she was until the transformation was all but complete.”

Ginger’s rage was also very intentional.

“Becoming empowered makes her furious,” Walton said. “Because there's so much that needs to be just torn up and start over because this world is not built for me. That's partly her werewolf talking and that's partly, yes, the frustration of coming of age. That frustration, that rage is about reckoning with who you are in the world if you've been born into it as a woman.”

As much as I loved Ginger, and still do, the movie isn’t perfect. The whole metaphor sort of falls apart toward the end as horror tropes take over in a bloody climax. That suburban setting always rubbed me the wrong way, too. I grew up not far from where the film was shot, in Markham and Brampton and my own East End Toronto borough of Scarborough. Even in 2000, the population of those areas was at least half people of color, yet the only representation of that in the movie is an Asian janitor who’s an implied pedophile and meets a violent end. Walton told me the movie “is undeniably an artifact of its day, in terms of representation.” These imperfections have jumped out more strongly at me as I’ve grown up and rewatched Ginger Snaps, but so too has my fondness for Ginger.

There have been few films in the genre that treat womanhood with the sort of care and room for anger that Walton wrote. Jennifer’s Body, written by Diablo Cody and starring Megan Fox, has some of the same themes, and certainly Carrie’s scenes involving periods and buckets of blood ring familiar.

But there’s never been another Ginger. Even now, when I’m in my thirties and my rage is more of a background hum than a hormone-driven scream, I turn to her when I want to remember my own need to tear everything to pieces. ●