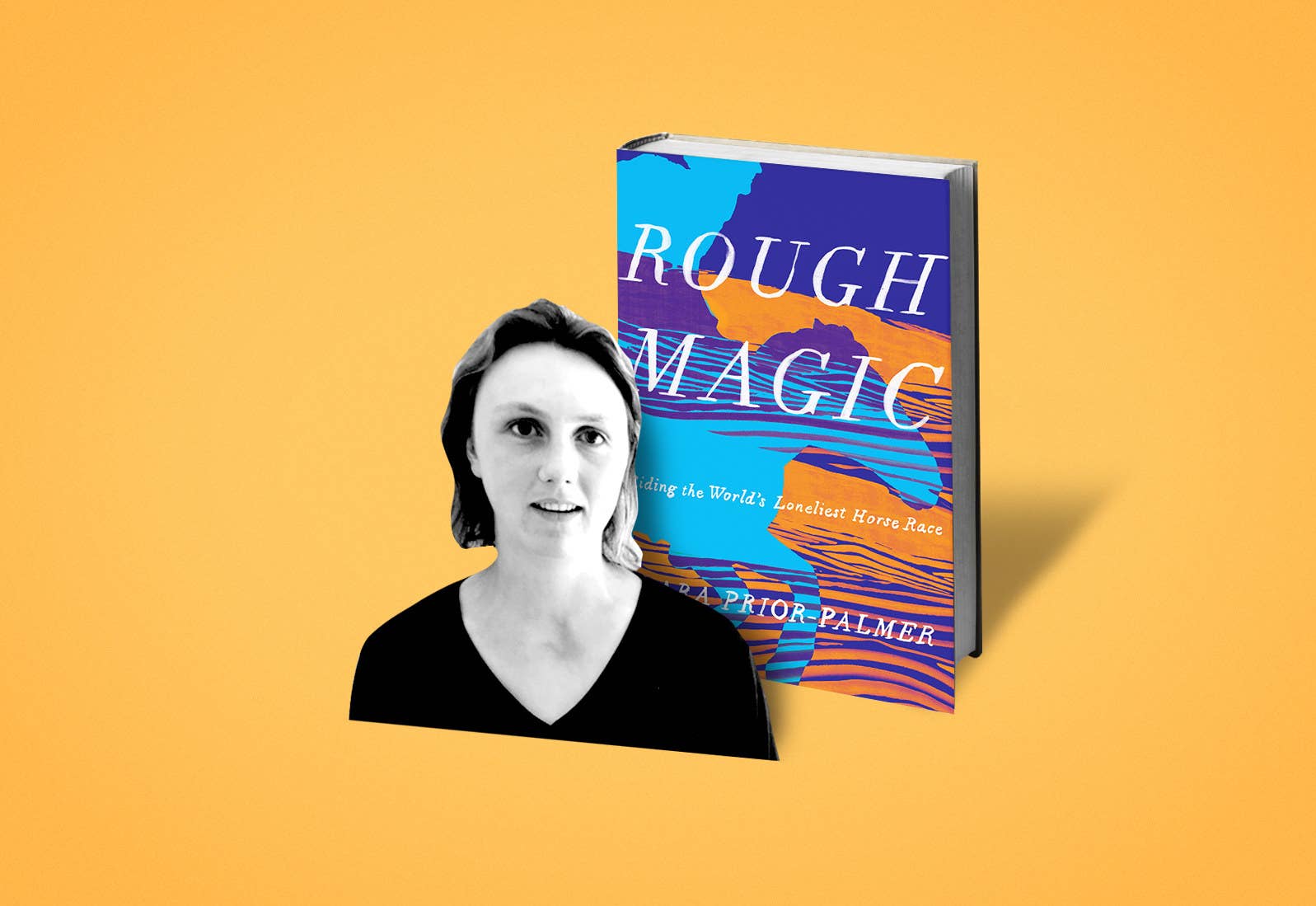

We’re so excited to announce Rough Magic as BuzzFeed Book Club’s June pick! Lara Prior-Palmer’s captivating memoir describes her impulsive decision at 19-years-old to sign up for "the world’s longest, toughest horse race” — 10 days on 25 ponies, over 1,000 kilometers of Mongolian grassland — and her surprising success despite having no formal training or qualifications other than a love of horses and great competitive drive.

Read an excerpt from her first day of the race below, and join us next month as we dive into the book — posing questions, sharing opinions, and interacting directly with author Lara Prior-Palmer.

The jeeps disappear. Riders splay out into the unknown. My pony is slow. We fall from group to group until we’re alone. He plods up a rise in the land, one hour in. I will call him “Brolly” after the leg, because of his speed to the umbrella at the start. “Gelatinous disc of a jellyfish” is the dictionary’s fourth meaning for “umbrella,” and Brolly now drifts in a jellyfish fashion, awaiting a current to carry us. Wild horses often move with the weather. With no coming storms to bluster his backside, Brolly and I fall so far behind I can’t even see any dots of riders ahead.

Where to go? I was hoping to follow someone. Every minute I scan the horizon in search of the next station. I almost lose my balance taking in the transparent distances. I can see only sun. Her heat is swelling me, I feel I no longer fit inside my body.

Apparently the horse stations, or urtuus, are formed by two or three white gers and a horse line. Earlier in the summer the Derby’s head horseman Unenburen Uyndenbat traveled the steppe with race organizers to ask families if they could bring 30 to 40 ponies together to make an urtuu. Some steppe families have as many as 200 horses and can create a station singlehandedly; others team up with neighboring herders. On the days when the riders are expected to arrive, the selected ponies wait around the urtuu horse lines, and the families charge the organizers for each pony competitor’s ride.

As far as I can tell, there are no urtuus in sight. I’d imagined the medieval postal system the race is re-creating as a series of stations spaced according to the contours of the country; I thought I might always be able to see the next station on the horizon.

From my denim vest pocket I unleash the one, the only, the cumbersome Garmin eTrex GPS: a thing like a mobile phone from the 1990s, coated in gray rubber with a small screen. I have been too scared to turn it on, in case my very touch tampers with its highly strung technological heart. Now it is blinking to life and rudely suggesting we’re only a quarter of the way to the first station.

It must be past lunchtime when my pony and I head out of the plains towards a mountain range. Sweat is dribbling over my eyelids, and the cross-strap backpack is digging into my ribs. I have run out of water. My mouth is dry. I think of lancing Brolly’s veins and drinking his blood, Mongol-warrior-style — Chinggis Khan and comrades rode horses to near-death on the campaign trail — but as we totter on, old Khan is forgotten. The medieval re-creation seems a farce. At the level of each beating hoof, this race superlatively long and tough might turn out to be chronically ordinary. We’re just trotting a path through grass.

I look at my watch again, five minutes since I last looked at it. Time becomes a tool for passing time itself.

Brolly is thirsty too. The map book instructs us to seek water in wells, rivers, lakes, ponds, springs, and waterholes, none of which we’ve passed. I sneak a Sesame Snap from my pocket and munch in rhyme to Brolly’s trot. Then I look at my watch again, five minutes since I last looked at it. Time becomes a tool for passing time itself.

As we curve each valley corner, we set the plains behind us free. Grasslands pull the summerscape in every direction. Green, green, gulping us up. Where the grass ceases, blue sky begins, translucent and bold. “Blue and green should not be seen, without a color in between,” begins my mother, babbling in my head wherever I go. “Blue and green should be seen,” she carries on, reminding me of the philosophy behind her jewelry making, which marries emeralds to sapphires at every opportunity.

Brolly, a young soul under old fur, is ever slower. My, just a horse race, don’t be silly. Between each urtuu are roughly 40 kilometers, and I have no idea how far that really is. It will turn out to be neither here, nor here, nor there at the bottom of the page. It is nestled far outside this rectangle.

I rise up, I sit down. I rise up, I sit down. A thousand beats of trot and still the scenery won’t shift. Nor are there any nooks or lonesome trees for me to chat to. As soon as I’m tempted to get upset, the undetailed land sits on my drama, as if to say, I don’t give a damn. Brolly and I are mere passersby. A train of bad thoughts. He blows through his nose most beats. I snort in agreement. Forgive me for asking, long girl, but would you allow someone to balance on your back in this manner? God no. Rather die, I would. Than be possessed like this?

Well, I’m not sure I really like being aboard a horse, either. I can’t believe it’s taken all these years to hit me again — my original sentiment. It’s visible in a photo of me age three on Costa, my cousin’s Shetland pony. I should stare boldly over the pony’s head — carefree niece of a champion — but my eyebrows are swept together in a frown. I want to return to the ground where my brothers stand, flanking Costa’s shoulders. To be up here, in this pose, is strange and exhausting: legs strained, back stiff, knees hinged.

We enter a burnt valley, green grass paled to yellow, earth chapped and bare. A series of creases forms the unreachable hills ahead.

So this was how racing would be? A serious struggle, or perhaps an unserious struggle. If I did manage to finish, I was probably going to be last — nothing I minded when it came to exams, but I couldn’t stand the idea of it in a race.

Apparently the matter in our bodies only makes up a tiny speck of dust. It has something to do with the distances between our atoms being so vast — as vast as the distances between urtuus. To the people I wrote to before departure, pleading for charitable donations, I was exactly this, I suppose: a tiny speck among other bunched specks. I hated the idea that I could be seen now, even in minuscule form, as I rode. I wanted to purge myself from the radar. Was anyone I knew even looking at the tracking map? I’d told my charitable sponsors that 40% of riders never made it to the finish. Some of my parents’ friends had taken the trouble to write encouraging notes like I do hope you don’t get a sore behind.

As the hours rolled by, voices leaked in — the future’s past-tense voices. What stories would they pluck from the skies if and when I disappeared from the map?

Her armpit hair grew too long.

She missed the plums and her father’s blackened toast, his figure by the slowly roaring fridge.

My journey aboard the first horse climaxes when I enter a silent tantrum. Perhaps I believe this tantrum will offer escape. That it will transport me home, where I shall strip my wallpaper, sharpen all the pencils, and lavish myself in mundane things that could have been just as exciting as this race if only I’d used my imagination.

I relocate myself in June, back when I was looking forward to this race with such romantic ideas, of dancing ponies on blankets green.

I can’t be sure we’re going the right way — the GPS is not clear, much less the landscape. I look about the valley and wonder where I’m headed, and indeed where my head is. How much of us is really moving forward if Brolly has already given up? After swinging south of the mountain range, the cat is truly out of the bag: He hates this. I get off and walk next to him.

At home, the pain of animals makes me shiver: when the dog whines after stealing too much salted butter or falls ill with testicle pain, or when my brother Arthur taunts me with “I’m going to put Hammy in the oven” and I shriek over the fictitious fate of my hamster. Now, at the center of a signless valley, I can offer no solution to the gray pony at my side.

As we go like treacle towards the hill, I relax out of my tantrum into a more bland potato state of mind. For some minutes, I relocate myself in June, back when I was looking forward to this race with such romantic ideas, of dancing ponies on blankets green, of dazzling scenes and legs so keen. I don’t know which wise man coined the saying “Life begins outside your comfort zone,” but Brolly and I have proven him wrong. Life, whatever that is, has gotten a wagonload worse. Stuck in a sludgy slow-motion, still walking at Brolly’s side, I move with my usual stomachache and dull thoughts of a missed lunch. Quitting the expectation game, one horse at a time.

We’re two kilometers from the station when a herder in a maroon cloak trots into our universe. He makes choppy gestures for me to remount, so I wing my legs back onto Brolly, whose eyes are now surrounded by gunk. The man leans over to whip my dear plod every stride. I see how his technique keeps Brolly trotting, and I question why I didn’t use it too.

The urtuu ahead is formed on a lull of earth that rises to tumbling rock formations. A steppe town glistens on the heat-waved horizon. At the urtuu I will hand Brolly over to the vets for assessment. Because our leg has taken five hours, the other riders will be gone by the time we arrive.

Propped on a bank before the station is a Soviet-era camper van. An interpreter and a paramedic crouch at its wheels, hiding from the sun, perhaps thinking, Yawn, here comes another rider. I am just a piece of driftwood, floating down the stream.

“Am I the last?” I ask.

Th ey’re surprised I didn’t know. “Yes, apart from Matthias.” ●

Copyright © 2019 by Lara Prior-Palmer, from Rough Magic: Riding the World's Loneliest Horse Race. Reprinted by permission of Catapult.

Lara Prior-Palmer was born in London in 1994. She studied conceptual history and Persian at Stanford University. In 2013, she competed in the 1,000-kilometer Mongol Derby in Mongolia, sometimes described as the world’s toughest and longest horse race, and became the first woman to win the race, and the youngest person ever to finish. Rough Magic is her first book.