At mealtimes, Khedr’s parents move their 16-year-old son to a seat at the table, as if everything is normal.

As his family speak to one another, spread butter and jam onto toast, and pour tea, Khedr is silent. His eyes are closed, his hands resting on a grey blanket his mother has placed over his knees. He doesn’t eat the toast; instead, a thin tube snaking into his nose provides liquid nutrients.

Khedr’s family, part of the Yazidi religious minority, fled Turkey in 2010 and sought asylum in Sweden. But after the family had yet another application for permanent residency denied by the Migration Board in 2016, Khedr fell into a deep withdrawal.

He is among the hundreds of refugee children in Sweden who have been diagnosed with resignation syndrome, or uppgivenhetssyndrom, since the early ‘00s. Children with the syndrome withdraw from the world around them, ceasing to speak, eat, drink or use the toilet.

Eventually, they enter what appears to be an unconscious state, and can live in this stupor for years as life goes on around them.

“Resignation syndrome is a condition ... where the soul and body disassociate,” Dr Elisabeth Hultcrantz tells BuzzFeed News. “They are separated, in a way.”

Hultcrantz is a retired ear, nose and throat specialist and emeritus professor at Linköping University, who now spends her time volunteering with the Doctors of the World charity. She drives back and forth across Sweden, visiting refugee families to test blood pressure and check muscle strength in children who have, as she puts it, fallen away from the world.

It has been reported that resignation syndrome exists only in Sweden, that it is an illness with a mysterious capacity to respect national borders. But in recent months, an outbreak of the same withdrawal symptoms has unfolded among children on the tiny Pacific island of Nauru, where the Australian government has left some refugees and asylum seekers to languish in offshore detention for more than five years.

The offshore detention centre on Nauru is notoriously difficult for journalists to access.

Hultcrantz granted BuzzFeed News rare access to visit the families of three refugee children with resignation syndrome in Sweden, in the hope that seeing their plight may soften the Australian government’s hardline stance.

BuzzFeed News visited three refugee families who have kids with resignation syndrome in Sweden. Watch their stories:

There are two common factors among children diagnosed with the syndrome: they are psychologically traumatised, and they have lost all their hope.

“Something has happened within their families, something terrible has happened,” Hultcrantz says. Khedr’s mother was raped, and his little brother – just two and a half years old – was killed before they fled Turkey, the family tells BuzzFeed News.

The illness is entwined with the uncertainty and strain of seeking asylum. Khedr’s entire family lives under the shadow of deportation.

“It is not predictable, they don’t know how long they will stay where they are,” Hultcrantz says. “But they have no positive hope about the future.”

The children on Nauru and their parents have been indefinitely detained in one of the world’s harshest immigration regimes. Their grim existence is a warning: if you’re thinking about coming to Australia on a people-smuggling boat, don’t.

Former Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull explained the system to US president Donald Trump in a phone call last year.

“It is not because they are bad people,” Turnbull said, according to a leaked transcript of the conversation. “It is because in order to stop people smugglers, we had to deprive them of the product. So we said, if you try to come to Australia by boat, even if we think you are the best person in the world, even if you are a Nobel Prize winning genius, we will not let you in.”

Trump replied approvingly: “You are worse than I am.”

Experts say the five-year ordeal in detention has caused people to lose all hope. Now, the catastrophic psychological consequences are manifesting in the body.

As she examines Amir*, a teenage boy with resignation syndrome who fled Russia with his family in 2009, Hultcrantz delivers a running explanation of signs and symptoms, what is normal and what isn’t.

“When we measure his blood pressure here we see he has too high blood pressure for his age,” she says. “He is 135 through 81. And he also has a high pulse rate. So it’s 126 heart beats per minute, and that is too high. And this is a sign that he is in distress right now, although it looks extremely peaceful, this condition.”

Amir looks impossibly serene. Were it not for the thin tube taped across his cheek, partially obscuring his faint mustache, he could be sleeping. But the signs of deterioration are there: his arms and legs are thin under his striped t-shirt and track pants, and the edge of a diaper is visible when Hultcrantz pulls up his top. He has lost 7kg in the two years he has had resignation syndrome, even though the nutrition seeping into him is calculated to his age and height.

Hultcrantz applies an ice pack directly to his stomach. It elicits no reaction, other than leaving a red patch on the skin. His blood pressure and pulse stay constant.

Amir’s parents are too fearful to speak on the record, petrified they might be identified and found. But they want the world to see their son. In preparation for the visit, they have set out tea and coffee, and a large plate of sweets. "If you have lots of sweets in your home, God will give you a sweet life,” Amir’s older brother says.

Her fingers resting on Amir’s temple, Hultcrantz uses her thumbs to gently prise open his eyelids. His dark eyes fixate on nothing. “He is just staring in front of him,” she says.

Amir may look unconscious, but we do not know for sure how cognisant he is of the world around him. Studies of resignation syndrome suggest varying degrees of awareness, and varying degrees of amnesia in recovery.

There are other unknowns. A prominent paper on the syndrome, published in 2016 by Swedish researcher Karl Sallin, hypothesised that resignation syndrome is not a new phenomenon, but an example of catatonia, with cultural factors driving the unusually specific and prolific spread among refugee children in Sweden.

The same, or very similar, symptoms are referred to under different diagnoses and names around the world. In Australia, advocates at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC) refer to the symptoms afflicting children on Nauru as traumatic withdrawal syndrome.

Trauma expert Naomi Halpern explains the syndrome as part of a defence mechanism hardwired into humans, and all mammals, for when we encounter overwhelming or threatening situations. Flight is usually the first instinct — in short, “I need to get away”.

If you can’t run, your brain might activate fight. “Whether it’s an animal or a person who feels backed into a corner, it’s like they get a surge of adrenalin and they come out fighting,” Halpern tells BuzzFeed News.

If neither fight nor flight is an option, you freeze. “It's like, 'There is nowhere for me to go, I can’t run, I can’t fight my way out, I’m not safe. The only way I can protect myself is to completely shut down'.” That’s resignation syndrome.

According to the ASRC this shutdown response makes sense in an environment like Nauru, where bitter politics have resulted in indefinite detention, resettlement options have failed, and the energy and desire to fight back has been almost entirely eroded. The sense of helplessness, and hopelessness, is extreme.

It is also “entirely predictable”, according to Dr Louise Newman, a professor of psychiatry at Melbourne University, the director of the Centre for Women's Mental Health at the Royal Women's Hospital, and the convenor of advocacy group Doctors for Justice.

Newman, a former chair of the Australian Immigration Health Advisory Group, which guided the government on the health of asylum seekers in detention, tells BuzzFeed News politicians were “very well advised” of the risks.

“That’s why we feel very strongly that they’re probably more culpable now than they were in the first round of detention,” says Newman, referencing the introduction of offshore processing by former prime minister John Howard in the 2000s. “The evidence is quite clear. And they continue to maintain this.”

There are multiple layers to the trauma and stress faced by kids on Nauru, Newman says.

“There is trauma if they’ve come from somewhere where they’ve been traumatised, there’s the trauma of the journey, there’s the trauma of detention. Then there’s the trauma of these really extreme things they’re exposed to. As some point, the bucket is full. And they just collapse.”

A fact sheet published on the ASRC website ends with a sentence in bold: “These children cannot recover on Nauru because Nauru is the cause of their trauma.”

With hundreds of resignation syndrome diagnoses over the past two decades, Sweden has developed a system to accommodate children such as Khedr and Amir. The trigger often comes in the form of a migration decision: a denial of permanent residency, or a notice of deportation.

Sometimes it is the children themselves, able to pick up the language of their new country more easily, who are saddled with the “terrible responsibility” of translating that bureaucratic rejection to their parents.

“It was so difficult to explain it to my parents,” Khedr’s brother Ali says. “To say that we had [been refused] from the immigration, I was sad about that.”

Ali, 17, has an unusual perspective on resignation syndrome: he has lived through it. He became sick with a milder form of the illness in 2011, when his family was first rejected by the Swedish Migration Board, but recovered after a few months.

“When I see my brother now, I can see that I have also been like this before,” Ali says. “It’s sad to know that.”

The migration notice has a re-traumatising effect, Hultcrantz says. Onset of the syndrome can be rapid or gradual.

After his family was rejected again in 2016, Ali says Khedr just stopped eating: “I ask him, ‘Why you don’t want to eat?’, he just said, ‘I don’t want to eat’. He refused to eat. And everyday he just got sicker.”

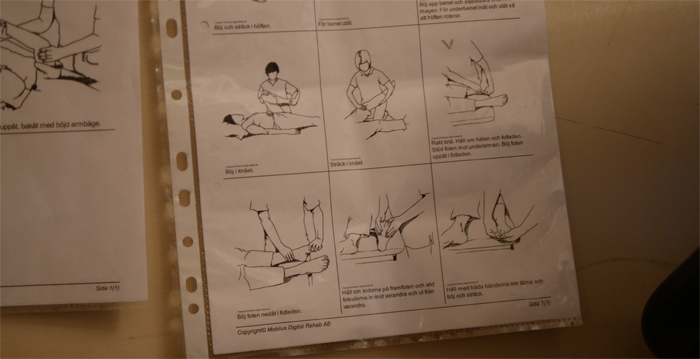

Inevitably, after a few days with no fluids or food, the child ends up in hospital. There, they are given intravenous fluids for rehydration. A feeding tube is inserted in their nose. Parents are trained on how to care for them – changing the tube, massaging and stretching unused muscles – and then the children go home. And then everybody waits, and hopes they recover.

“I try to do everything right,” Ali says. “Try to talk with him everyday. I take him out some days also. I read books to him also. I try to do everything, so he can come back to us.”

On Nauru, there is no such system. The issue of inadequate medical treatment on the island has grown in prominence since a landmark court case in 2016 found Australia had a duty of care for the refugees and asylum seekers it had detained offshore.

The problem can essentially, but somewhat inadequately, be boiled down to this: refugees and asylum seekers often have complex health problems that are either caused, or compounded, by ongoing detention; Nauru has insufficient medical facilities; and for political reasons the government doesn’t want to bring people to Australia for treatment.

Lawyers and doctors involved in offshore detention advocacy can’t believe a child hasn’t died during the mental health crisis that has unfolded on Nauru in recent months.

According to the ASRC, which coordinates legal bids to force medical transfers to Australia, more than 30 children have been brought to Australia for urgent treatment. Many of them have attempted suicide, have self-harmed, or are suffering withdrawal symptoms. About 95 children, many of them with the same symptoms, remain on Nauru.

“Some of these parents literally sit there night by night watching their child and trying to force water into their mouths,” says Newman. “This can go on for weeks and weeks and weeks.”

Several court decisions have ordered children to Australia on the basis they need to be in a paediatric inpatient unit, where they can be placed on an IV drip for rehydration, a nose tube for feeding, have tests run for their kidney, heart and brain function – and, crucially, be under the supervision of an adolescent psychiatrist. But facilities of this calibre are simply not available on Nauru.

The kids who have made it onto a plane to Australia are at a “late stage” of withdrawal, Newman says.

“These are the children who are in a coma, who are not able to eat or drink, who have no response to voice or touch or pain, who have no reflexes,” she says. “It’s a very deep state of withdrawal and it’s life threatening. Those are the ones who got out.”

Stark differences in medical care aside, the children in Sweden and on Nauru share an unenviable commonality: a lack of hope.

The consequences run from quotidian to severe. For example, Amir’s older brother has been talking to a girl. He wants to date, but is dealing with a problem: he can’t commit. He’s that guy, he explains with a half-smile, and when things start to get serious, he runs.

But his reasoning is more sound than your average 23-year-old: he can’t work, he has no sense of stability, and he has to live in refugee housing with his family. He has a brother who is extremely ill. He can’t offer anything to a girlfriend, he says. It’s for these reasons that he won’t allow himself to fall in love.

This uncertainty, and underlying trauma, can envelop entire families. The focus is usually on the severely ill child who is withdrawing from the world, but the parents watching on, who are often also unwell, become increasingly despairing over the condition of their child, convinced they are watching them die.

“I tell the parents the child is not suffering any longer, but you are suffering,” Hultcrantz says. “Because it is a terrible situation when you see your child disappear in a way.”

Khedr’s mother, Almas, who has endured terrible trauma of her own, says it makes her feel “like there is no life for me” to see her son so ill.

“Of course we were hoping for a good future for our children in Europe,” she says, on the verge of tears. “But it is far from what we expected here.”

“The child is the one who in some ways symbolises what’s going on for everyone, and everyone gives up,” Newman says. “That’s why we are very clear ... that the treatment of this condition has to be to support families to find some resolution to their situation, so they can cope. So parents are able to support the children.”

But finding a resolution involves politics. Politicians in Australia and Nauru have a history of ascribing ulterior motives to the reports of poor mental health, self harm and suicide attempts streaming from Australia’s offshore detention centres.

Earlier this month, Nauruan president Baron Waqa claimed kids on Nauru were being “pushed into doing something that they are not aware of” by refugee advocates and parents. “It's the way of working the system, probably short-circuiting it, just to get to Australia,” he said.

Newman says you cannot fake resignation syndrome. It is not a hunger strike, and it is not pretending to be asleep. She also says that suicidal tendencies in young children are very rare and a sign of tremendous distress.

“The thing we have to be very careful of is that governments and others will argue for political reasons that this is simulated, or put on, or bad behaviour. Conscious manipulation. And from a psychological point of view, none of it is conscious.

“You don’t consciously think, ‘Oh I think I’ll go into a coma’. It’s just an incredibly naive thing to say … you can’t will yourself into a coma where you feel no pain. That’s actually a physiological thing. It’s the way the body responds to this condition of the mind.”

Many medical practitioners and researchers in Sweden – Hultcrantz among them – say the best way to treat resignation syndrome is to grant permanent residency to the families afflicted by it.

“Apart from life-sustaining tube feeding, treatment amounts to promoting and maintaining a secure and hopeful environment, encouraging a sense of coherence,” said Sallin’s 2016 research paper, published in the journal Frontiers of Behavioural Neuroscience.

The paper stated that “Several authors stress the importance of a permanent residency permit”, but added that a permit in and of itself neither guarantees recovery nor prevents onset.

This further blurs the lines of an illness that is already hard to fit into boxes: psychological in origin, physiological in manifestation, and, seemingly, political in solution.

Hultcrantz stresses that people with resignation syndrome need security and hope – a notion she terms “soft values” – to recover, and not just medical intervention to stay alive. But conveying such concepts to migration officials and sceptical governments is difficult.

“These so called ‘soft values’, they are not really written in the textbooks in medicine, nor in the legal books,” Hultcrantz says. “It’s also very difficult to talk about security and hope in medical certificates.”

In the reports on various children Hultcrantz writes for the Swedish Migration Board, she tries to explain.

“It’s not the nutrition, the tube feeding, per se, which is needed for the treatment of the child. It is needed otherwise the child will die in a week or two, but it will not cure them … and it is the cure we are working for. We want the child to be a playing child again.”

But how does a child who tapped out from the world for months, or even years, come back to life?

About a month ago a teenage boy and his family were airlifted to Australia. He had lain in bed in Nauru for five months as his muscles wasted away, to the point where medical staff wondered if he would be able to walk again.

Three months into his ordeal, his younger brother also started to withdraw, ceasing to talk, eat, or drink. The boys, who also attempted suicide multiple times while on the island, went in and out of the Nauru Hospital. Their parents carried them to the toilet, and bathed them in their beds.

Since receiving hospital care in Australia, the siblings have improved. They are now drinking, eating and talking again. But both lost a significant amount of weight in their deterioration, and they fear a return to Nauru.

Advocates generally wield legal instruments to prevent refugees being sent back to offshore detention after they are medically transferred to Australia. The crisis on Nauru is so recent – and ongoing – that there are still plenty of unknowns about how kids who were withdrawn or suicidal will recover. But the change of environment appears to be working.

“When we remove them, they recover,” says Natasha Blucher, the detention advocacy manager at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre. “It’s in line with the Swedish experience. You see there that once they were granted a permanent visa, they were able to feel hope and stability, and they should come out of that state. Because once they move out of Nauru, they’re in a healthy environment.”

Recovery is not rapid, simple, or even linear. Blucher and Newman say most of the children who have been brought to Australia are still receiving treatment.

“They go up and down,” Blucher says. “There was a child who came off [Nauru] in February. She was doing excellent at school, was starting to cope, get her resilience back, had made friends. But a couple of weeks ago, she had to be taken back to emergency because she started hurting herself again.”

In Sweden, Hultcrantz has witnessed many recoveries. She has even become Facebook friends with some of the teenagers she met while they were sick.

“Usually I come in when they are already laying there,” she says. “So I haven't seen them when they are healthy. And to get to know a child afterwards, that is very rewarding.”

After permanent residency is granted, the atmosphere in a home shifts, in a way that is somehow perceptible to the catatonic child. There is simply more sound, more life in the people around them.

“First the siblings are more joyful,” Hultcrantz says. “And of course the parents, I mean they all sit around the child and they touch the child and they hug the child and say, ‘We have got permission to stay, it will be happy, wake up, please, please’.”

But it takes time for a sense of security to set in. Nightmares and persistent stress will linger in parents and children alike. Usually over a period of months, Hultcrantz says, you can begin to feed the child, and then they will start to open their eyes.

Deep emotion can also act as a stimulant, she says. One girl began to cry when she heard her grandmother’s voice through the receiver of a telephone, held up to her ear.

“When she heard that the tears began to run, and that was emotional, and that was the start, we really brought the grandmother here then, and that was the first time, then she woke up,” Hultcrantz says.

Hultcrantz says she has devoted her retirement to resignation syndrome for these moments. “Because I know that the children can be healthy again, they are not damaged for life if you take care of them.”

In the years before 16-year-old Bahar became ill, she would tell her mum “I don’t want to go back to Syria, I want to stay here in Sweden”. She was terrified by media coverage of the atrocities perpetrated on Yazidi women by the Islamic State.

But she was also a happy teenage girl, a committed school student who wanted to be a police officer when she grew up. She entered puberty in the years before she fell ill; she finished developing in the throes of the syndrome, lying in bed.

Her younger brother is 12, and dreams of becoming a professional soccer player.

“It doesn’t feel nice to not know 100% whether you can stay or not. But I really like it here, so I try to think I should [make] the most of it while I’m here,” he says.

His tender gift to his big sister is pop music. “Before she got sick she loved to listen to music, so what I do is I put on some good music on my phone and I leave it next to her so she can enjoy it.”

Bahar’s vital signs are relatively good. Her pulse is fast – a sign of distress – but her blood pressure is normal, and her spinal cord reflexes are working fine.

Hultcrantz picks up Bahar’s arm, positions it over her head and drops it. It falls limply onto Bahar’s face.

“She has no protection reflexes,” Hultcrantz says. “If you take her arm and let it fall like this, it just drops over her nose without her blinking or anything.”

The same reaction – that is to say, nothing – would happen with other types of pain stimulus too, like a pinch, or a needle, Hultcrantz says. This means Bahar is in the deepest level of resignation syndrome.

She has been sick for a year, and her family has been waiting for permanent residency in Sweden for a decade.

“But that's it, everything is working perfectly well,” Hultcrantz says, finishing up her assessment. “With the right conditions she will wake up again and be completely healthy again. And become a policeman as she wants to be.”

*Not his real name.

If you or someone you know needs help, you can contact Lifeline's 24-hour crisis support and suicide prevention hotline on 13 11 14 in Australia. Trauma resources are available at phoenixaustralia.org. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org.