Justice Michael Wigney’s face was grim, devoid of the jollity that had regularly surfaced last year during the Geoffrey Rush defamation trial, as he swept into court on Thursday afternoon to complete his unenviable task.

Every seat was taken in Courtroom 18C, one of the largest in the law courts building that looms over the northern end of Sydney’s Hyde Park. The number of chairs in the public gallery had more than doubled for the spectacle.

A lone TV camera was set up at the edge of the jury box, ready to carry a livestream of Wigney to the world. Next to the tripod, journalists occupied the jurors’ chairs.

“This is a sad and unfortunate case,” Wigney began. “It plainly would have been better for all concerned if the issues that arose in the saga that played out in this courtroom in October and November last year had been allowed to be dealt with in a different way, and in a different place to the harsh adversarial world of a defamation proceeding.

“But they were not. And so it comes to this.”

This was Rush, one of Australia’s best known and most successful actors, suing News Corp publisher Nationwide News and journalist Jonathon Moran over articles alleging Rush had behaved inappropriately towards an unnamed female cast member during the 2015-16 Sydney Theatre Company (STC) run of King Lear.

The articles, Wigney said, came “in the midst of the ‘Harvey Weinstein scandal’ and the worldwide explosion of the phenomenon which later became known as the #MeToo movement”.

Typically a #MeToo story involves a person, most often a woman, relating an experience of sexual harassment or assault on their own terms. Not in this case. Rush’s accuser was revealed in court proceedings as 34-year-old actor Eryn Jean Norvill, who had made a private workplace complaint following the production.

The Daily Telegraph became aware of the complaint and proceeded to air Norvill’s allegations, against her wishes, in the most dramatic fashion imaginable.

Rush sued. Norvill agreed to testify for the newspaper at a late stage, giving it a shot at a defence of truth. A three-week trial put both of them on the stand. And now, as Wigney said, it had come to this.

“O, you are men of stones!” begins his judgement, which runs well over 200 pages.

This line is uttered by King Lear in Act V Scene III of the play, after he staggers onstage cradling the dead body of his youngest daughter Cordelia, howling and shattered by his grief.

This scene is pivotal, both to the play and to this defamation case. It is the moment in which Lear reckons with the extent of his folly; having reconciled with his banished daughter at last, he has now lost her again. Mad with regret, he keels over and dies, in the grip of a false hope that she is breathing.

It is also the moment in which Norvill, who played Cordelia in the STC production, alleged Rush, who played Lear, deliberately traced his hand across her right breast as they acted out this challenging scene in a preview performance, in front of more than 900 people.

The touch was “slow and light and pressured”, Norvill told the court in November last year. “It didn’t feel like an accident.”

Rush strongly denied intentionally groping Norvill: “Did a thumb accidentally touch the lower part of her chest? Possibly. I wasn’t monitoring this with detachment.”

Like everything in this case, the issue is far more complicated than those contradictory sentences. There are pages and pages of evidence about the alleged touch. Director Neil Armfield testified he was watching “like a hawk” and saw nothing. Actor Mark Winter said he “unequivocally” saw Rush cup Norvill’s left breast on stage.

In the end, Wigney accepted Rush’s story, finding it had not happened. This was, in part, because he believed Rush was such a dedicated actor, so utterly devoted to his craft, that he simply would not have done anything to jeopardise such a vital scene.

“Was it even remotely plausible that Mr Rush, as the consummate professional, would have taken such a risk for such a fleeting moment of supposed sexual gratification?” Wigney asked.

It was one of six allegations made by Norvill that were rejected entirely by Wigney.

The judge was not satisfied Rush had made a groping gesture over Norvill’s torso as the entire cast rehearsed that same grieving scene. He did not find, on the balance of probabilities, that Rush had rubbed the small of Norvill’s back on two occasions as they waited in the wings, just before he lifted her and she went limp in his arms, playing dead. And he was unconvinced that Rush had ever made lewd gestures or suggestive comments towards Norvill in rehearsals more generally.

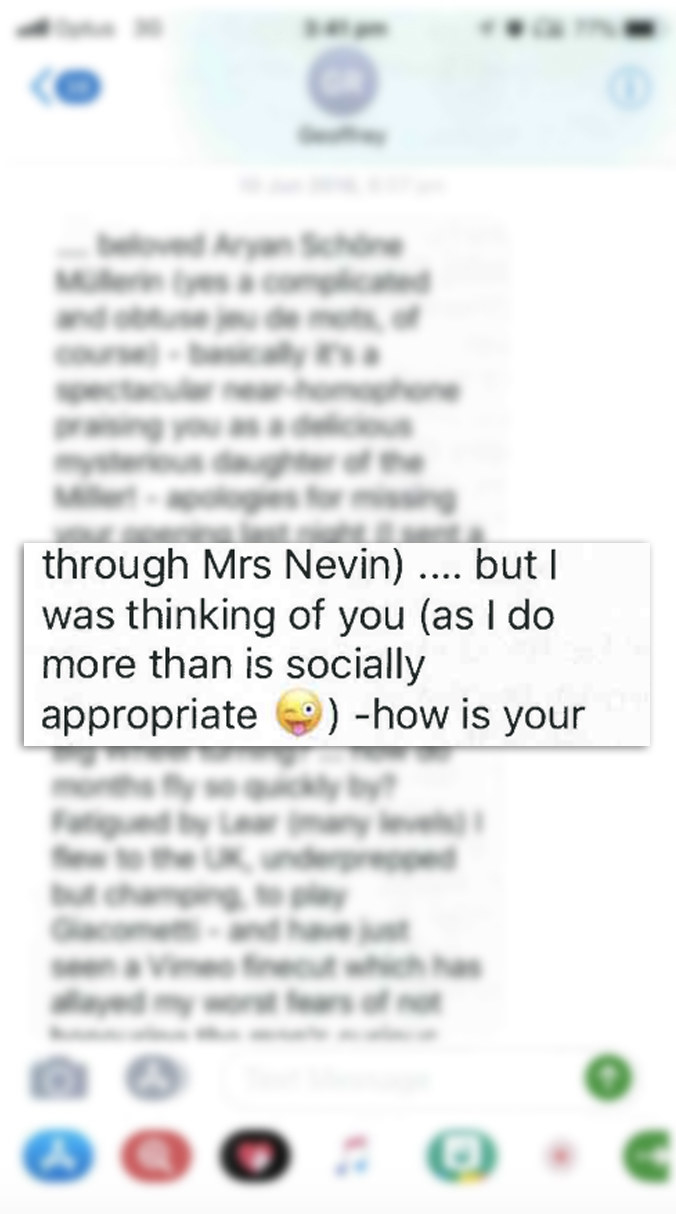

Two more incidents raised as evidence of Rush’s inappropriate behaviour — telling a journalist he had a “stage door Johnny crush” on Norvill, and a text saying he thought of her “more than is socially appropriate”, accompanied by an emoji winking and with its tongue hanging out — were found to be nothing more than light-hearted banter, incapable of proving anything about Rush’s behaviour.

As for the Telegraph, Wigney labelled the articles about Rush “recklessly irresponsible” and said it was “sensationalist journalism of the worst kind”. The now infamous “KING LEER” front page, he said, was particularly unfair.

It was a clean sweep. A stunning victory for Rush, and just as stunning a defeat for the Telegraph.

For Norvill, it must have been devastating.

The judgement contains, in effect, a 150-page evisceration of her testimony. As Wigney read aloud a summary on Thursday, she was seated in the front row of the packed public gallery, listening attentively. Her head was tilted at a slight angle, her face betrayed no emotion.

The judge had not given her testimony an inch. But why didn’t he believe her?

Wigney issued a plea before he left the courtroom: “I would simply ask this. That before you judge my judgement, [as you are] perfectly entitled to do, I ask that you read my judgement, so that you can fully appreciate the reasons.”

The “most compelling” reason to doubt Norvill’s credibility, Wigney wrote, is that her evidence was simply not corroborated. It was largely contradicted by King Lear actors Robyn Nevin and Helen Buday and by Armfield, who all testified for Rush. Even Winter’s testimony provided “little support” on close analysis, Wigney found.

Her evidence was also inconsistent with details in an email penned by STC employee Annelies Crowe, the person to whom Norvill first confided her accusations about Rush’s alleged behaviour.

These two significant matters ran across Wigney’s judgement, contributing to his general view of Norvill’s evidence. Each allegation was also dealt with separately, in detail.

Take the breast touch. It seems that Rush’s devotion to acting was the major sticking point for Wigney, who detailed this issue first, and at length. He also factored in the absence of other witness accounts or stage notes referencing the alleged incident, as well as Armfield’s evidence that he did not see it. He found that Winter’s evidence had major inconsistencies with Norvill’s account, was broadly unreliable, and delivered in a strangely “matter-of-fact” way.

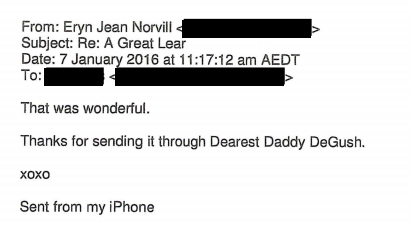

But Wigney also found Norvill’s account was “completely at odds” with an email she sent Rush on Jan. 7, 2016, about six weeks after the preview performances. Rush had sent her a positive review, and she replied:

“That was wonderful. Thanks for sending it through Dearest Daddy DeGush. Xoxo”

(The nickname here is in keeping with other correspondence between the two, including a series of text messages in 2014 where they regularly employed florid nicknames to address one another, such as “Giddy McHeadRush”, “Galapagos Lusty Thrust” and “Erogenous Navel”.)

On the stand, Norvill was asked to explain.

She said that after not complaining about Rush for so long, she was just “trying to keep it normal” and make it to the end of the show.

“I felt trapped by my own silence, I guess,” she said. Norvill also said that she had written the email in “survival mode” and, not wanting to risk the performance, “I chose to put Geoffrey’s comfortability above my own”.

Wigney was unpersuaded.

“Ms Norvill could have kept it normal without referring to Mr Rush in the playful and fond terms that she had employed in the past,” he said. “She could have kept it normal without signing off with hugs and kisses.”

Giving evidence, Norvill was adamant this was not the case. She said she “wrote in poetry” to Rush, and a concise “Thank you” or the like would have generated tension.

“Not the kind of email someone in your position would send, is it Miss Norvill?” said Rush’s barrister Bruce McClintock.

She replied sharply: “Absolutely someone who was in my position sent it, because I sent it.”

This email was not the only thing Norvill did, wrote or said that was taken to diminish the credibility of her evidence.

She spent hours under cross-examination and was asked multiple times why she had acted in the way she did, in the face of all this alleged behaviour. Why hadn’t she complained to someone? Why hadn’t she said “stop it”? Why had she continued to praise and engage with Rush?

But many of the explanations she offered were taken by Wigney as either unpersuasive, or as an indication she was an unreliable witness.

One example was her praise of Rush in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald promoting King Lear in Nov. 2015. "I love Geoffrey's ebullience,” Norvill is quoted as saying.

“No-one put a gun to your head and made you say that, did they?” she was asked on the stand.

Norvill later asked a question in reply: “What was I supposed to say?”

She gave an example: “‘Oh, and by the way, I don’t know if Geoffrey has the right intentions towards me. I don’t find his jokes that funny, actually; they make me feel small as a human’,” she said. “What was I supposed to do?”

Again, Wigney was unpersuaded. Sure, it was unreasonable to expect Norvill to make allegations to the journalist, or to criticise Rush in a promotional interview, he wrote. But it didn’t follow that she was obliged to make positive statements about him — let alone “highly complimentary” ones.

It was in this same interview that Rush declared he had a “stage door Johnny crush” on Norvill.

Wigney accepted Rush’s evidence that he intended the comment to be funny, and a compliment.

“It may perhaps have been a poorly selected and regrettable expression to use to praise Ms Norvill,” Wigney wrote.

“However I reject the contention that Mr Rush was intending to depict Ms Norvill as a ‘sexual object rather than as a serious skilled actress’ or that he intended to make Ms Norvill feel uncomfortable, embarrassed and compromised.”

A third example was her statement that her fellow cast members were “complicit” in Rush’s behaviour towards her in the rehearsal room, either unable to see it as wrong or unwilling to step in.

This statement displayed “a propensity to exaggerate and embellish”, Wigney found.

He also rejected something else Norvill said in this vein, about Nevin: “We’re from different generations. Maybe we have different ideas about what is culturally appropriate in a workplace.”

Was it possible Nevin, Buday and Armfield did in fact witness Rush’s behaviour but just didn’t think it was wrong because of their age?

No, said Wigney. First of all, the suggestion was not put to them on the stand. Second, “even putting that to one side, each of them was a highly-qualified, experienced, accomplished and well-respected, if not revered, figure in theatre circles”.

Third, the notion that any of these people would not have known what to do, or would have been fearful to approach Rush, was “difficult to accept”, Wigney said.

“In the case of Ms Nevin and Ms Buday, even putting their impeccable character and integrity to one side, both of them gave every impression of being an independent, strong-willed woman who was not [to be] reckoned with,” Wigney said.

And yet it was difficult to ignore the generational themes that ran through this case.

Norvill was 34 at the time of trial, Winter was 35. Backing Rush was Armfield, 63, Nevin, 76, and Buday, 56.

Nevin testified on King Lear generally: “There was quite a marked division in that cast between the younger actors and the more experienced actors.”

She said Rush had never commented on her body or made lewd gestures towards her.

“I am sure, though, Mr Rush has told me in the past I looked attractive or pleasing or something, I am sure because he’s very generous in his enthusiasm towards people,” she said.

Asked if she found it offensive she said no, never.

Buday laughed when the Telegraph’s barrister, Tom Blackburn SC, suggested the text Rush had sent to Norvill was not an example of “responsible mentoring”.

“Do you think it’s appropriate for Mr Rush, aged 65 as he was then, to say to this young aspiring actress that I was thinking of you as I do more than is socially appropriate?” asked Blackburn.

“I’m astounded you would find this in its context in any way inappropriate,” Buday told the barrister.

The exchange, during which Buday infamously imitated the emoji and broke into song, became heated. Eventually she fired at Blackburn: “This, I find a delightful text. That’s my answer. I hope that’s really clear. Is it clear?”

At one point in the trial, Blackburn and Wigney discussed Norvill’s evidence that Rush had called her “scrumptious” and “yummy” in the rehearsal room.

“In this day and age Your Honour, members of chambers would not go around saying to their female colleagues in the morning ‘you look scrumptious today’ or ‘you look yummy today’,” Blackburn said.

“It wouldn’t happen in a registry of this court, and nor should it happen in the theatre, was Miss Norvill’s point.”

Wigney said at the time that he didn’t think he would use the word “scrumptious” in any context, “not even to describe food”, but that an older person might, and Blackburn’s argument required grappling with the notion that different people might interpret things differently.

He ruled on Thursday that “context is everything” when it comes to whether it would be appropriate for a man to call a woman’s appearance in the workplace “scrumptious or yummy”.

“I do not accept that it is invariably or necessarily inappropriate, let alone ‘scandalously inappropriate’ to use such words in a workplace setting when talking to a woman,” he said.

Wigney also said that, compared to the texts Rush and Norvill sent, the words seemed “quaintly old-fashioned and harmless”.

It is, finally, worth noting that Wigney did not find Norvill had lied. There is a difference, however small, and however redundant at this point in time, between a witness who is not credible, and one who is dishonest.

Wigney said she appeared to be “endeavouring to give an honest recollection” of events, but also noted that people could offer unreliable evidence for all sorts of reasons. Their memory might be “poor or defective”; it may have become “distorted or polluted”; the witness might honestly believe something had happened when it in fact had not.

“In all the circumstances I do not think that it is possible to reduce the factual issues and inconsistent evidence in this case to the simple question of whether or not Ms Norvill is a liar, or has told lies,” he said. “The issue is not as black and white as that. Life is not that simple.”

Unfortunately for Norvill, in many respects, it is that simple. The distinction is already lost in the wash, swept away by the magnitude of Rush’s victory and the Telegraph’s — and her — defeat.

After court adjourned, Rush, looking deflated, told journalists: “There are no winners in this case. It has been extremely distressing for everyone involved.”

He is walking away with the clearest vindication one can get in a defamation case, as well as $850,000 and more to come. But I am not sure if anybody who attended the trial and heard the evidence of Rush’s family and friends could reasonably believe this judgement signals an end to this, for him.

Robyn Kershaw, the producer of the film Looking For Alibrandi and iconic TV series Kath & Kim (in which Rush and wife Jane Menelaus once guest-starred) began to cry as she recounted how her friend had changed in the wake of the articles. “He was incredibly laden with grief, to the point where he couldn’t talk about anything else except what he was personally experiencing,” she said. “He stopped laughing, which is something I have actually always loved.”

It was Menelaus who offered the most intimate and the most devastating portrait of how the entire affair had changed her husband. “I saw a man so altered and changed. His eyes sunk into his head. He retreated very much from, well, from the world,” she said.

She also wept on the stand, as she recounted watching TV with Rush to try and take their mind off things only for him to burst into sobs at a scene that reminded him of King Lear. “It’s very painful to relive something we’re actually trying terribly hard to forget,” she said.

“Our 11 months, I would say, were like Groundhog Day, except in Groundhog Day, it’s the same day. With this, it got worse and worse and worse.”

Defamation law expert David Rolph said there are instances in which lawsuits seem to be the best or only option for restoring a person's reputation, but going to court is a “crude mechanism” that can often end up magnifying the hurt and distress caused by defamation in the first place.

“Reputation is fundamentally what people think about you,” he said. “In many instances it’s difficult to use the law to compel people to think differently about you.”

Perhaps it is true that Geoffrey Rush won, and also that there are no winners.

About 10 minutes after Rush and Menelaus disappeared down Phillip Street, pursued by several cameramen, Norvill emerged from the law courts exit and turned left. It was difficult to comprehend how she must have been feeling. It seemed as if she was on the brink of tears, and that the only thing holding them back was a steely resolve.

“I stand by everything I said at trial,” she said, not loudly, but forcefully. “I told the truth. I know what happened. I was there.”

She did not dwell on how the case came to be, only saying “I never wanted these issues dealt with by a court”.

“This case has caused hurt for everyone,” she said. “There are no winners, only losers. And I would've been content to receive a simple apology and a promise to do better, without any of this.”

She said she was grateful to Yael Stone, who came forward to make allegations about Rush on the ABC TV’s 7.30 program, in an interview that aired on Dec. 17, 2018. Rush has denied acting inappropriately towards Stone.

Stone’s interview is memorable — not for the salacious details, but for the nuance in her perspective. Stone said she had a friendly relationship with Rush and exchanged playful text messages with him. She agreed that could have given him the “confusing” impression that she welcomed his behaviour, and said she wasn’t proud of how she had behaved at a time when she was 25 and he was 59.

“I would add that consent is very complicated. And almost impossible in a dynamic where the power is so drastically imbalanced,” Stone told the ABC.

“And I would say in any working environment, where there is that imbalance of power, the subordinate doesn't have a great opportunity for expressing themselves freely. So the onus is on the more powerful person not to put the subordinate in that position.”

Outside court, Norvill said: “It has to be possible for a young woman working in theatre, who feels unsafe in her workplace, to get that situation fixed.”

Going forward, she intends to devote a lot of time to making this a reality, and is also eager to return to acting.

Times are changing rapidly, and industries need to change with them, Norvill said.

“We can do it, but only if we acknowledge and confront with honesty the problems and the complexities of the power imbalances in our workplaces.”