A young woman, her pregnant belly visible beneath a blue t-shirt, is walking down the street in Derby, a town of about 3,300 people in Australia’s remote northwest corner.

It’s 9am and Derby is already baking under the Kimberley sun, the mercury nudging 33C. Later, it will reach 39C. For visitors, it’s very hot — particularly for May, which across most of Australia is the final month of autumn — but for locals, this time of year marks the start of the dry season, a blessed departure from the sweltering humidity of the wet.

It is cool, at least, in the van driven by youth mental health worker Marietta Walkerbier, 38, who is navigating the backstreets, dressed in the colourful polo shirt of the Derby Aboriginal Health Service (DAHS).

“Where’s she going?” Walkerbier says to herself as she passes by the woman, before swinging the van around and lowering the window. “You want a lift or you right?”

The woman says she is just heading around the corner, but Walkerbier cheerfully insists. “Well, jump in. You might just pop when you’re going home!”

As soon as the sliding door closes, with a swoosh and a thud, the questions start. How are you? Where are you getting your antenatal care? Have you had a check-up for the baby?

The woman says she missed an ultrasound appointment.

“Well you gotta go and check-up just so they can look for baby, how baby growing inside. They can catch if anything wrong straight away,” Walkerbier says, encouragingly. “And no drinking, you know?”

Walkerbier pulls up in front of a house. “Alright tidda. Go on,” she says. The woman climbs out. She’s been in the van for 67 seconds.

Walkerbier explains this is what's known in Derby as “Toyota therapy”.

It takes just over two hours to drive from Broome to Derby, 220km eastward into the vast and rugged Kimberley.

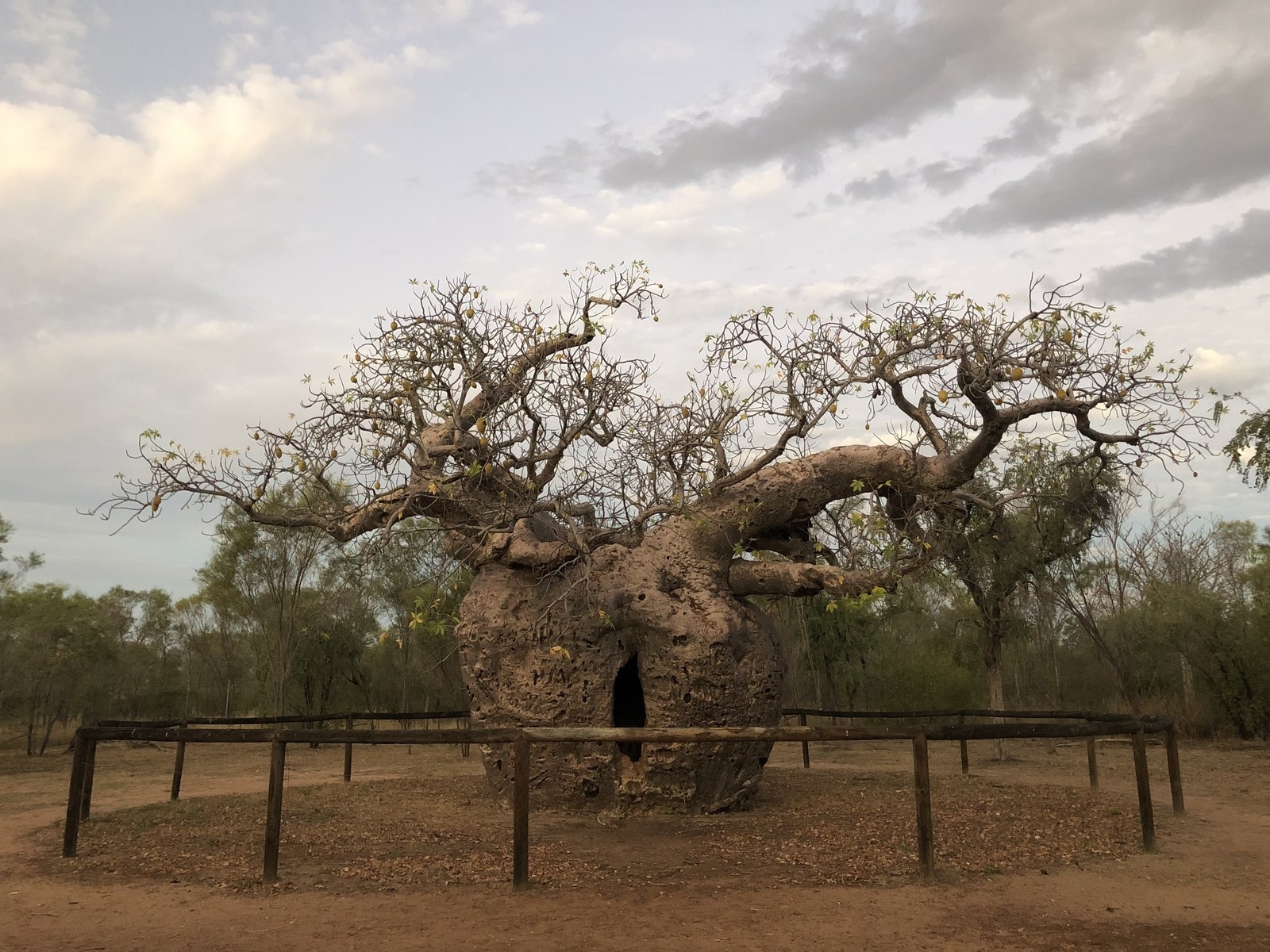

The sealed road is bordered by brilliant red dirt, the land on either side dotted with termite mounds and stray cattle that appear to munch serenely, but are prone to dashing across the road. As you travel inland, boab trees start to appear, their bulbous trunks and unruly foliage almost otherworldly, like a work of science fiction.

The region is sparsely populated, with 34,000 people spread across 423,000 square kilometres. More than half of them are in the two biggest towns — Broome in the west and Kununurra in the east. Just over 40% of residents are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander; across Australia, the figure is 3%.

Alongside its beauty and isolation, the Kimberley is also known for its suicide rate. Last year, Indigenous health minister Ken Wyatt told the World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference: “If [the Kimberley] was a nation, it would have the highest suicide rate in the world.”

About eight years ago, Derby was at the epicentre of this ongoing catastrophe. In 2011 three young people died by suicide in as many weeks. The following year, the Aboriginal community of Mowanjum, 10km out of town, was rocked by the suicides of six people within six months.

Trent Ozies, 27, is a Djugun man from the Broome area who grew up in Derby. Ozies also has Filipino, Chinese and European heritage, as well as a gentle manner and a thoroughly infectious laugh. But he is grave as he recalls this terrible period.

“It was almost as if we went full circle,” he says. “Someone passed. Had their funeral, had the wake, someone passed. Had the funeral, had the wake, someone passed.”

As he speaks, Ozies holds a fist in the air and moves it slowly in a circle, stopping to punctuate each point of the cycle.

“The dangerous thing about that is that people started to become desensitised. The shock of somebody suiciding was no longer there,” he says.

It got to a point, Ozies says, where if somebody said goodbye to you, you would hold onto that moment for an extra second. “I mean, I’m sorry to say it, but at that time you never knew who was next.”

That sense of dread is known across the Kimberley. In February this year coroner Ros Fogliani released her report into the deaths of 13 Aboriginal children and young people who died in the Kimberley between 2012 and 2016. Fogliani found that 12 of the 13 had died by suicide and delivered an open finding for the remaining death.

Fogliani found that these individual tragedies were shaped by the “crushing effects” of poverty and intergenerational trauma — meaning the way in which the extraordinary harms of colonisation and the Stolen Generation are passed down from parent to child, imprinting on each new generation of Indigenous youth.

The flow-on effects of this trauma, Fogliani wrote, include “domestic violence within families, alcohol and illicit drug abuse, child sexual abuse, poverty, neglect, low school attendance, lack of employment opportunities, overcrowding in houses, poor physical health and untreated mental health conditions”.

Toyota therapy?

“It’s opportunistic. It’s covering all the bases,” Walkerbier says, as she pulls away from the house. “She’s pregnant. It gets the information out. No drinking — we’re trying to tackle FASD [Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder]. Checking up, you know. And just a bit of encouragement, you could say, for her and baby’s wellbeing.”

Walkerbier and her coworkers use Toyota therapy a lot. Sometimes it’s a chance check-in, sometimes a 40-minute counselling session.

Psychologist Maureen Robertson tells BuzzFeed News there are lots of reasons someone might not go to the clinic: kids to look after, family violence, physical health issues.

“They’re OK to go for a drive though,” she says. As it turns out, the van is an unexpectedly convenient venue. Robertson says you can strap “the littlies” into a car seat in the back and let them enjoy the air conditioner while mum — or dad, but usually mum — talks in the front.

People open up in the car more than you might think, says Walkerbier. “You can solve – not solve,” she corrects. “But you can tackle.”

Walkerbier, of the Kija people from the east Kimberley, grew up in Derby. She left town aged 20 and returned 18 years later, after stints in Alice Springs, Darwin and Kununurra, where she worked in suicide prevention. Now, she is the Aboriginal youth mental health worker on the DAHS Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) team.

The concept of SEWB is important. It is ingrained in Aboriginal healthcare and is a holistic version of what mainstream providers call mental health. SEWB recognises that wellbeing for Aboriginal people is inextricably linked to culture, land, community and kin. It also reckons with the ways in which Australia’s racist history has affected Indigenous health.

Robertson, a 68-year-old white woman who has lived in Derby for two years, is sitting on a comfortable red couch inside the SEWB unit, of which she is the manager. The team is based in a converted old house that has a homely, not clinical, feel. They would like a new building, but don’t have the money. The five workers see all age groups for a range of issues — anxiety, depression, grief, loss, anger — and liaise closely with the doctors at DAHS.

Cultural barriers can make seeing a doctor in a mainstream service a fraught experience for Aboriginal people. A person who uses English as a second or third language may lack the words to describe how they are feeling. Things like not making eye contact — a sign of respect in some Aboriginal cultures – can be misread as a patient not engaging.

At DAHS, and particularly at SEWB, access is a priority. “We want as many people as possible to be able to access these services,” Robertson says. “And we see that as our responsibility.”

Flexibility runs through everything the SEWB team does. There is an open door policy: come on in for a chat, no appointment necessary. There is the Toyota therapy. There are youth groups. Their work ranges from counselling to mentoring to advocacy, depending on what a person needs.

Linda Abbott, the perinatal worker, says she often bonds with clients — or, as she calls them, “my ladies” — by assisting them with the endless paperwork that comes with living in state housing.

“I’ve spent just now an hour and 10 minutes going through forms for one lady who’s just got her house,” Abbott says. “It’s a nice entry point for them to give me the honour of coming into their lives at a more personal level.”

The SEWB house also functions, at times, as a drop-in centre for local kids. The staff are all very busy, but there is a standing policy on this front — five minutes of quality time.

“That usually involves making them a Milo, maybe making them a cheese sandwich if we’ve got the supplies,” Robertson says. “[Asking] ‘How are you going, what’s been happening, have you been at school today?’ Mostly it’s ‘yeah’. ‘OK, you know, is everything OK at home?’ Just that little bit of safety. Finding out if there’s anything that’s worrying them.”

The boys and girls who drop in can be “a bit naughty” around town, Robertson says. “But when they come in here, every one of them is a special, wonderful, gorgeous kid that’s incredibly worthwhile and they know that we think they’re really great. So they come back again and again.”

The flow of kids made the staff think: should we make this into a program? Find some funding? But with structure comes bureaucracy.

“Then we’ve got to meet KPIs,” Robertson says. “We’ve got to report against this little bit of money, we’ve got to put down facts and figures. What we’ve got at the moment is we’ve got the kids engaging because they want to engage and we want to encourage that.”

There is one thing they ask. “You can come and have good fun with us provided you go to school,” Robertson says. “We’ll pretty much do anything to encourage that.”

DAHS lost state funding last year for its psychologist and Aboriginal mental health worker positions.

Aghast at the prospect of losing Robertson and Ash Bin Omar, who works extensively with men, boys and families, DAHS decided it had to self-fund the positions. But money doesn’t grow on boab trees, and CEO Lynette Henderson-Yates doesn’t know how much longer they will be able to find the required $330,000 per year.

“We need those two positions given everything that’s happening in the community,” she says.

“People know them, they trust them, they will work with them. And it takes a long time to build up that trust with Aboriginal people.

“So for us not to have a psychologist and an Aboriginal mental health worker is really crazy. To my mind, there’s no debate about whether you have them or not have them.”

Senator Pat Dodson, who will become Indigenous affairs minister if Labor wins the election on May 18, told BuzzFeed News a Labor government would look to provide Commonwealth funding for those two positions.

“I visited that clinic, I’m very impressed with the work that they’re doing,” he said. “I know how essential that work is. I would hope that once, if we are elected, that they would be in receipt of funds to sustain the good work that they’re doing.”

Labor has pledged $30 million over three years to support Aboriginal mental health and SEWB services in three high-need regions, including the Kimberley.

Dodson said it was essential to employ psychologists and Aboriginal frontline workers to connect with young people and try to stem the flow of tragedy.

“If you don’t have these people being employed through the community health services, it just makes the effort to try and assist young people from taking these extreme measures totally impossible,” he says. “There’s many other things that have to be done, no doubt, but this is just one area.”

Indigenous health minister Ken Wyatt told BuzzFeed News in a statement that the $19.6 million for suicide prevention pledged by the Coalition “builds on existing funding” currently received by DAHS.

It would come through the Indigenous Advancement Strategy, which provides about $55 million per year for SEWB, Wyatt said.

The sum includes $15 million for the rollout of mental health first aid training in 12 Indigenous communities, and for youth in high risk communities, as well as continuing training for frontline workers such as rangers and night patrol.

Another $4.6 million will go towards community-led programs — designed to complement existing services — in areas such as leadership, sports and culture.

The Kimberley is one of 12 suicide prevention trial sites across Australia, where the federal government is spending money to try and answer the question “How do we stop people from killing themselves?”

Ozies is the Derby community engagement officer in the trial, tasked with devising and implementing programs.

He has five plans in motion, ranging from getting helpline numbers on the training singlets of the local footy team, through starting up community healing forums, to running workshops in which people are taught how to talk to their families about suicide.

“Everyone talks to their family members,” Ozies says. “You don’t have to be close to them, but they’re your family. You’ve gotta know the way that they behave, the way they talk. Is it different? Is there a reason why it’s different? Is this recent, something I should be concerned about? If I am concerned, how do I go about it?”

Ozies is trying to change “old-fashioned thinking” about suicide, and break down the stigma around accessing services.

“If you’re talking about suicide you’re not going to cause someone to suicide,” he says. “That’s a common misconception, that if ‘I talk about it, I’m going to give them an idea’. Well, no. They’ve already got that idea inside them.”

Over lunch at the Spinifex Hotel Ozies stresses the importance of the close-knit relationships in Derby and in Aboriginal families. Community is intrinsic not just to his programs, but to his life. When we need a quiet place for the interview, away from the music playing at the pub, he calls a friend who works at the local Aboriginal corporation, Winun Ngari, and we head down the street to use a meeting room.

Another friend is there working reception. Leslie Taylor is a 20-year-old transgender woman, who is close to Ozies. The pair are related, and share the special bond of being openly LGBT in Derby.

“People think because we fit into a certain group or a category that we are not strong,” Ozies, who is gay, says to Taylor, as they stand out the back. “But the reality is, in Derby, through our conversations, you don’t feel like people judge you.”

“There were a few challenges here and there but that’s just part of life and growing up,” Taylor says. “That’s what gave me the thicker skin to be who I am as a person … hiding behind a mask, that’s just totally not me. I’m more or less an open book.”

Ozies has informally counselled Taylor over the years, and says their relationship demonstrates the need for 24/7, non-judgemental services.

“A lot of the stuff I’ve mentored Leslie with has been outside of those work hours,” he says. “It’s been at tough times. It’s been stereotyped as high risk hours, it’s on the weekends when services are closed, it’s late at night when there is no-one to talk to, or you feel like there’s no-one to talk to. On top of that, we’re human. Sometimes alcohol or drugs are involved. Sometimes mental health comes into play.”

Taylor says she knows what it is like to be in a dark place: “I’ve been down that road quite a few times but I had to make that move, bring myself up, lift myself back, put the pieces of positivity together, and go out and get what I wanted.”

How did she do that?

“Confidence within,” she says. “It was definitely a hard thing to do. But when you’ve got good support like Trent here for one … you can go and achieve as much as you want to do.”

As Walkerbier drives through the Derby backstreets, she waves at pretty much everybody, providing a running commentary: who lives where, what this building is used for, which family has recently had someone die, meaning Walkerbier must go and do sorry time, or mourn, with them.

One woman comes over for a chat, and Walkerbier asks what she thinks of SEWB. We need it, she replies, referencing all the suicides. People have to have someone to talk to.

On the next street, Walkerbier pulls up alongside a young girl, walking alone.

“Hey, haven’t seen you. What you been up to?”

“Nothing,” the girl replies.

“Not going to school today?” Walkerbier asks.

“I am.”

“You are! Good on you.”

The girl is a member of SHINE, a group for at-risk girls aged 12-18 that Walkerbier runs on Tuesday afternoons. At the group, which counts as school attendance, the girls learn about things like healthy eating, personal hygiene, alcohol and drugs.

But it is also about widening horizons. Guided by Walkerbier, girls who might regularly truant or misbehave at school can realise their strengths.

“They might be disruptive in the classroom,” Walkerbier says. “But when they [are] here, I see them as leaders.”

Recently, Walkerbier took a group of the girls and their mums out on country, to the place where their great grandmother was born. The girls left their phones at home and slept on swags in an open shed, lined up in a row on the concrete slab.

“Aboriginal people, we heal on country,” Walkerbier says. “We do a lot of soul searching on country. And it just gives us, while we’re on country, a better understanding of our problem and our issues.”

She worries about the effect of social media, saying the girls are trying to fit in and deal with bullying, and often the mothers or grandmothers bringing them up do not know how to cope.

“Having to walk two worlds for those families is very hard and very new,” she says. “Also [the girls are] not engaging with their parents because they’re always on their phone.”

One way the mothers do get through to their kids is via Walkerbier.

“I have the mums say, ‘Can you talk to this one for being naughty?’,” she says. “The mums can’t talk to them, you know. They know they trust me, that I can talk to them.”

Many of the girls, from families struggling with poverty, violence, addiction and other social problems, crave affection and touch as well as guidance, according to Robertson.

“So you’ve got all these little girls just hanging off Marietta,” she says. “She’s not only doing all the mental health and self esteem, and you know this transition from childhood to teenage years and adult years, she’s doing a hell of a lot of mum work as well. Just giving them all that encouragement and support and love. Big shovelfuls of love, we call it.”

Rob McPhee is the co-chair, along with Ken Wyatt, of the Kimberley Aboriginal suicide prevention working group, and the deputy CEO of Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services (KAMS).

Speaking to BuzzFeed News at the KAMS office in Broome, McPhee has just returned from a series of meetings in Canberra. He says the Kimberley’s high suicide rates occur against a backdrop similar to that of Indigenous people around the world: dispossession of land, denial of language and culture, Stolen Generations.

But other aspects are unique: the sheer remoteness, the lack of jobs and economic activity, and “the relevance of Western education systems for Aboriginal people who have lived fairly traditional lifestyles and still practice culture quite strongly”.

“Ultimately it's about trying to find a way that we can balance the respect and recognition and role of Aboriginal culture and society in what's a dominant Western society that's been imposed since 1788,” he says.

He cites a 1998 Canadian research paper that found Indigenous communities with high self-determination in areas such as governance, land, policing and health had lower suicide rates.

The prevention trial is a “really good opportunity”, he says, but it is not the be-all and end-all. “I think the real solution is for us to have more control and put control back into communities.”

The peak body for Aboriginal community controlled health organisations, NACCHO, has been running a campaign this election urging both major parties to properly fund community health.

McPhee, and the Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, which is in the final stages of defining an SEWB model, will soon be lobbying hard for SEWB funding in particular.

He says the Derby unit is probably the most successful model around, in terms of community integration and treating mild to moderate mental health issues.

“Other mental health service providers are being given funding for Aboriginal mental health, but you know, we've proven over and over again, community control is the place where we should be resourcing,” McPhee says.

“You can see it in DAHS, you can see the way that that's embedded into Derby. But they're also at Jarlmadangah, they're up the Gibb River Road, and all of those remote communities ... it's completely immersed into that local community.”

On another recent SHINE outing, the group was given digital cameras and went out to photograph Derby. One girl in particular revealed an incredible eye.

“She’s 12 and she’s taking these photographs that are just like pieces of art,” Robertson says.

In the van, Walkerbier takes me to meet the budding photographer, who lives in Mowanjum community. “I try and do a lot for these girls out here because they miss out on the resources,” she says.

On the way out of town, we pass the turnoff to the Boab Prison Tree, an enormous specimen with a hollow trunk and a dark, disputed history. Visitors to Mowanjum have to sign in at the front desk of the community office, which Walkerbier and I do before before finding the young girl at her grandmother’s.

She appears behind the flyscreen door, and Walkerbier tells her to go get her photos. Thirty seconds later, she shyly emerges, clutching three printed A4 pieces of cardboard.

In one picture, the Prison Boab is blurry, framed by leaves in sharp definition; in another, it peers out between the diverging boughs of a eucalypt. The third photo is of a long cattle trough nearby, taken from a low angle, the water stretching out under the sun.

The girl poses with her work, smiling, and Walkerbier talks with her about how the trough picture demonstrates nature: the ripples of the water, the wind through the windmill, the oxygen from the trees.

It is easy to see why young girls look up to Walkerbier, see her as their mentor. She is funny and thoughtful, generous, without a trace of superficiality or judgement.

On the way back from Mowanjum, I ask her about the series of suicides in that community seven years ago. She begins to answer, but then tells me about a different loss instead.

“My sister completed suicide. She was 25. She was working in Argyle Diamond Mine [in the east Kimberley], and she was off on a two weeks roster break, and she came back here and she left two kids behind. Her kids, when she completed suicide, they were, the eldest one was seven and her youngest one was two.

“That was about 15 years ago, 16. Still, we haven’t gotten over it. We still feel it. That gaping big hole, and the question why. I think in my search for why, it kind of pushed me towards mental health,” she says, looking ahead at the road.

“That wanting to know, seeking my sister’s death, and wanting to know more of what makes someone take their own life. What’s so bad in their life that they couldn’t talk about it? Or if they did talk about it, why hasn’t it got better?”

Walkerbier says the loss of her sister is part of why she does what she does — lifting girls and young women up so they can see a future for themselves.

Along Loch Street, the main drag of Derby, there are boab trees dotted along a grassy median strip, kept green by sprinklers that run early in the morning.

The small town idyll is a stark contrast to the Derby backstreets, a minute’s drive away, and home to the public housing where many SEWB clients live. Life there is rough, marred by poverty, addiction and family violence. There have been a lot of suicides and suicide attempts in the backstreets, and there are also a lot of good people, says Walkerbier.

“Everyone, even though they got a fucked-up life, whatever, they all seem to get along,” Walkerbier says. “Get by with what resources they’ve got. They all share resources like milk, sugar, tea, alcohol, smokes. They got to put up with loud music at all hours of the night.”

Later, she adds that everyone there is traumatised: from their childhoods, from intergenerational trauma, from dysfunction. And, she says, from “not belonging” — the everyday, racist messaging that you are lesser.

“Why do they all stick us in the back streets?” she asks. To Walkerbier, it sends a clear message: “Get back there. We don’t want to see you. We don’t want to hear about your bullshit.”

Lynette Henderson-Yates says intergenerational trauma is “not easy to pull apart”.

“There are some people who are resilient enough to be able to recognise it and make their life a little bit different, live a different life,” she says.

But it is difficult to outrun growing up in a family that has experienced severe trauma, particularly when alcohol and drug problems, and other social disadvantages, are present.

“It’s to do with the fact that children were removed,” Henderson-Yates says. “Children were put into missions and didn’t learn parenting styles, or how to love.

“And I’m talking from my own experience. From my own family. Because my grandparents were taken away and put into missions. My grandmother in particular was very tough on my mother. And they didn’t really learn how to cuddle and love and whatever. It’s only through my generation that we’ve tried to break that and sort of parent a little bit differently.”

It comes with resilience, but also with vulnerability, particularly against a backdrop of poverty and a lack of education. Some people cope, others cannot.

“It’s actually very very complex. But it’s real,” Henderson-Yates says. “And the hurt is still there. That’s what I think a lot of Australians don’t realise, is that the hurt is still there.”

It is important, she says, that we don’t blame families for the visible dysfunction in communities: “These families are traumatised one way or the other.”

Some people working in Indigenous suicide prevention tell me they are worried about “deficit discourse” in the media: a relentless focus on failure and dysfunction, with little attention paid to people’s strengths.

There is evidence this can have real world outcomes, affecting health and education and contributing to racism, according to a 2018 report from the Lowitja Institute.

“Rejecting deficit discourse is not about pretending that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face no challenges, nor about downplaying those challenges,” the report says.

Discussing social problems and how to fix them is important and necessary, it says. But equally important is not defining Indigenous lives by that negativity, “eclipsing the complex reasons for inequalities, and overlooking diversity, capability and strength”.

A few years ago, Ozies became the first man to be crowned the Boab Queen — an honour bestowed each year during Derby’s fortnight-long Boab Festival, a highlight on the small town’s social calendar featuring multiple events, including a parade.

Winning that title, Ozies says, was a “turning point” in his life. It taught him that it was possible to alter perceptions; that even the most entrenched cycles can be broken.

“When you talk about suicide you have groups that are classified as higher risk, statistically. And I fit into quite a few of those categories,” he says.

He meets my eye as we sit on opposite sides of a desk in the small meeting room at Winun Ngari, two paper cups of water on the table between us.

“You and I are both 27. We’ve both acknowledged we are in the LGBTQI community. We both grew up in small towns,” he says.

“But the reality is that I’ve experienced a lot more trauma in my lifetime, that is supposed to increase my risk of being a statistic. So it’s hard. And I think my personality, and just the way I am, is trying to break those statistics and those barriers.

“I proved it on a smaller scale, winning the Boab Quest and being Derby’s Queen.”

Reliving the delight of that unlikely victory, Ozies laughs. Once more, he is determined to be the change.

If you or someone you know needs help, you can call Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14, Beyond Blue Australia on 1300 22 4636, or the Suicide Callback Service on 1300 659 467.