Grace Cockie’s baby Carmel is chubby and cheerful, burbling away at her adoring mother as they sit in the living room of their house in the southeastern suburbs of Perth.

“She looks at her big sister’s photo and she smiles,” Cockie says.

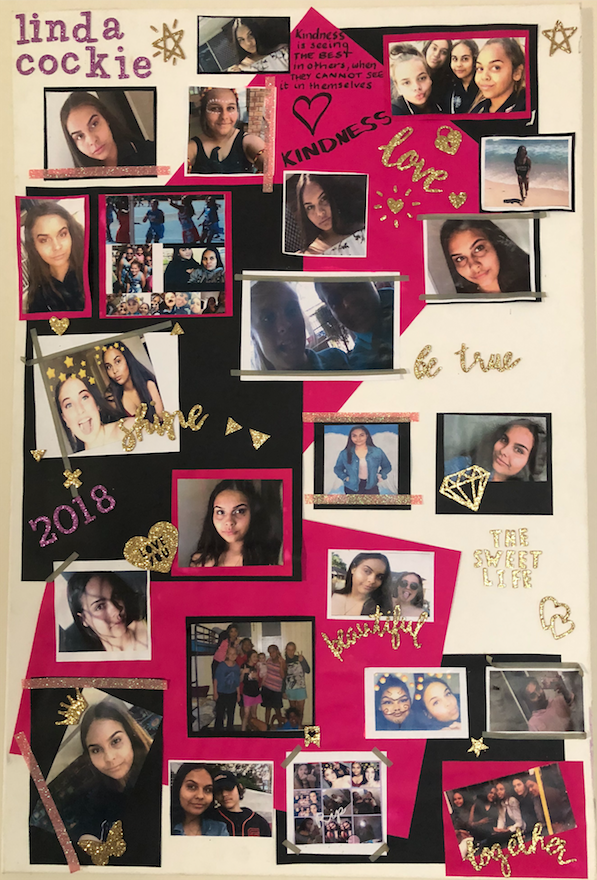

Tacked to the wall is a picture of Linda, Cockie’s eldest daughter, who died by suicide on March 17, 2018.

“I ended up falling pregnant at the same time my girl passed away,” Cockie says. “Nine months later in December, just before Christmas, another little girl.”

She exhales. Linda was 16 when she died, but to Cockie, she will always be “my baby”.

Her eldest child was her “little sidekick”, a happy-go-lucky girl who spoke her mind, listened to her mum, and helped around the house with her younger siblings.

“She had a beautiful voice. I always wanted her to go on Australian Idol or whatever, X-Factor,” Cockie says. “I said, ‘I’ll be your number one supporter’.”

Looking at Carmel, Cockie’s voice cracks. “It’s like God sent her here to heal me. To keep me, because … I’m broken.”

Cockie does not want any other parent to go through what she has. But a horror spate of suicides across the country in the first months of 2019 has seen 56 Indigenous people die by suicide, 14 of them children.

The suicide rate among Indigenous Australians is twice that of non-Indigenous Australians. For young people, those aged between 15-34, it is more than three times the rate.

Particularly in tight-knit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the ripple effect can be devastating. Research shows that when a person dies by suicide, it can elevate the risk of suicide among the people left behind.

The National Indigenous Critical Response Service (NICRS) was created to combat this reality, by directly supporting bereaved families following a suicide or other traumatic event.

The service was first trialled in Western Australia, and then received $10 million in federal funding, over three years, from the beginning of 2017.

Until recently, its national coordinator was researcher and advocate Gerry Georgatos. He tells BuzzFeed News the service has supported more than 300 families since its inception, amounting to about 60% of Indigenous families across the nation who have been affected by a suicide.

Despite the elevated risk, there have not been any further suicides in these families, Georgatos says.

“That’s a huge achievement, and we don’t close any case off. Their journey is predominantly one of poverty, and we work with them long haul.”

The operation is relatively small, with nine support workers across Perth, Geraldton, Darwin, Adelaide, Melbourne, Brisbane and Cairns. It will soon expand to Broome and Alice Springs.

One of those workers, Megan Krakouer, arrived at Grace Cockie’s door on the same day Linda died. Both Krakouer and Cockie are Noongar women.

“Her cousin is my cousin, and she connected us up,” Krakouer tells BuzzFeed News.

“That morning, when her daughter passed away, I went and sat with her, just for about an hour and just worked out what I could do. The thing she needed straight away was a bit of food, because there was a lot of family coming around.”

Krakouer organised the food. That was just the first step in the support process.

Cockie is the person who made the incomprehensible discovery of her daughter’s body at their last house. “I felt her skin and it was cold,” Cockie says through tears. “It broke my heart.”

Her voice falls to a whisper, the words barely perceptible through her grief. “Shattered it.”

She could not stay in that house. She told Krakouer, who spoke to Georgatos, contacted the state housing authority and got Cockie moved to new public housing as quickly as possible.

It has been more than a year now, and Krakouer still sees Cockie regularly.

“We’re trying to reduce the stress levels and helping people with that trauma recovery,” Krakouer said. “That’s just so important.”

Another woman Krakouer has been supporting is Amber Cox, a 26-year-old mother of four, who lost her partner CJ to suicide in October last year. He was 36.

It has barely been six months, and Cox is struggling.

“I'll have my good days and I'll have my bad days,” she tells BuzzFeed News, sitting at her kitchen table. “My bad days, probably like one of them today. Yesterday, and the day before.”

Cox is also living in public housing in Perth’s southeastern suburbs — the house organised with the help of Krakouer. Like Cockie, she was desperate to leave the house where CJ died.

“Aunty Megan pushed it and pushed it,” she says. “I'd ring and be like, ‘I can't be here’. So she rang and put letters in and stuff like that.”

CJ was an “awesome person” she says, a family-orientated dad of seven who loved cars and motorbikes. “He built things from scratch. He'd turn anything into something.” He also “had his issues”, experiencing depression and anxiety that was so severe he struggled to function, and self-medicated with methamphetamines.

What is her life like after losing him?

“People ask me that all the time. What is your life like?” she says. “If you think about it, I don't have a bad life. You know, I've got a house, I've got my kids. Considering the circumstances, I have my shit together quite well … just dealing with this is quite hard.”

Cox says she thinks constantly through the consequences of her decisions — fearful that if she puts a foot wrong, snaps at somebody in her anger and grief, that her kids will be taken off her.

“I'm sad as shit right now and if I drink now I will just explode,” she says. “I'll choose the people I hang around with very carefully. The company I keep. And I keep my shit contained.

“If I get on edge or something I'll go to my room, or I'll turn the music up like extra loud so I just can't hear no-one. But that's kind of what gets me out of my funk.”

Three of Cox’s four kids live with her, and she struggles to feed them on Newstart and a parenting payment.

“I don't have food in my cupboards because I can't afford to ... provide them food to last right through the week,” Cox says.

“Those are just everyday struggles. I buy food, it lasts three days, four days. Because they [are] hungry as shit from the last week, you know? They just eat.”

The help that NICRS workers can offer takes many forms: talking to grieving families, wrangling housing with the state authority, managing legal and financial issues, even driving a minibus full of relatives to the funeral. It is both deeply emotional and highly practical work.

Krakouer, who studied law, previously spent three years working with the Knowmore Legal Service, which was set up in response to Australia’s royal commission into child sexual abuse.

“One of the hardest things is going into a house where there’s lots of people and they’re grieving. A lot of tears, a lot of hurt, a lot of pain,” she says.

It’s difficult, but you just have to “keep it real”, Krakouer says. Go in with respect, the confidence that you can help, and a willingness to work with the family at their own pace.

“You can suggest things, but don’t come across overpowering, because if you turn around and do that at the most sensitive time, chances are people will say ‘Go along, we don’t need ya’,” she says.

“I’ve been into some really challenging situations. The one thing that will get you through is respect. And quick action, quick turnaround.”

How does she personally cope?

“I’ve got a good group of people around me and we’re just trying to make changes across Australia. That’s pretty much what keeps me going,” she says. “Don’t get me wrong, there’s times when you just want to cry. But you just have to keep going, particularly when you believe in something.”

“You know that if you don’t do something for a particular family, if you don’t come through, if you drop the ball, sometimes there’s no one else to pick that ball up. And you can’t leave people behind.”

Of the 56 Indigenous suicides so far this year, 54 of the people were living below the poverty line, Georgatos says. He believes poverty is the driving factor in the high suicide rate among Indigenous Australians.

“What’s killing people below the poverty line is not necessarily killing them above the poverty line. It’s about agency,” he says.

For instance, domestic violence: “There’s a reluctance for families to break up below the poverty line from family violence versus above, because they may end up in more severe poverty and homelessness than otherwise.”

Issues such as bullying and sexual abuse are the same, he says. “Sexual abuse is more likely to be not talked about below the poverty line, or supported with early intervention, validation and counselling.”

There are a variety of views on causes, risk factors and, ultimately, solutions, among the people working in Indigenous suicide prevention.

In February, coroner Ros Fogliani handed down a report into the deaths of 13 children and young people in the Kimberley region, finding 12 had died by suicide. She wrote that the individual tragedies were “shaped by the crushing effects of intergenerational trauma and poverty upon entire communities”.

Her report spoke at length about intergenerational trauma — the extraordinary harms of colonisation and the Stolen Generation being passed down through generations — and the damage it has wrought on communities.

Rob McPhee, deputy CEO of the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service, sees the way forward as improving Indigenous self-determination — things like implementing the Uluru Statement, reviving cultural practices, and returning community control to Indigenous people in areas of self-governance, health and policing.

Georgatos says education is the “most powerful protective factor” to reducing suicidal ideation and allowing people to navigate life, with all its stress and complexity.

Linda’s life in the years leading to her death had been tumultuous and dysfunctional. The family was kicked out of their long term public housing under Western Australia’s state housing three strikes rule, where tenants can be evicted after three instances of disruptive behaviour. The strikes, Cockie says, were actually instances of domestic violence, inflicted on her by an ex-partner.

The family became homeless and Cockie became addicted to meth. Her kids were taken off her, and after a long stint in rehab, she moved back into public housing with them. A few months later, Linda died.

“It’s like they set me up to fail,” Cockie says, tracing it all back to the moment she was kicked out of her home. She believes that if that had not triggered years of roiling instability, Linda would still be alive.

“It just gets me angry,” she says. “I should have been placed in a stable home for me and my kids.”

“It’s stable now,” she says, but it is also too late.

Cox doesn’t know what could have helped CJ.

He was in counselling, and had made suicide attempts before. He had also received news that he had a potentially fatal heart disease in the months before he died, she says.

But her message to people is a simple one — ask for help.

“It doesn't matter where you are, or if you're a man, woman, or child, there is help everywhere. Don't ever think that you're a burden on anyone.

“I don't think we need to bury any more people. Not by suicide, anyways. ‘Cause the pain doesn't end with that one who died. It doesn't. It passes onto the next ones.”

Georgatos is now the national coordinator of new organisation the National Trauma Recovery Project (NTRP), which is currently privately funded by donations and community grants.

The NICRS is about responding to suicide; the NTRP is about trying to prevent it before it happens. The outreach service will support people who are traumatised, who have experienced things such as sexual abuse, or suicide attempts, and work with them — intensely, relentlessly — to improve their lives.

“The saddest period for anyone who’s lost someone to suicide is actually after the burial. When you’re isolated, when you’re lost,” Georgatos says. “But we don’t want people in that position. We don’t want these impacts transmitted on to other members of the family. And we have an obligation to do what we can.

“The focus has to be on outreach. It has to be on working as closely as possible with families to support them and improve their circumstances to the best of our abilities.”

Georgatos says both services should receive Commonwealth funding to the tune of tens of millions of dollars — an increase to $30 million for the NICRS, and $50 million for the NTRP. Neither the Coalition nor Labor has specifically pledged additional funding to the NICRS during the election campaign.

Senator Pat Dodson told BuzzFeed News that if Labor wins government, it will look closely at “anything that’s going to get us better results than what we’ve got to date”.

“If it works and if it’s contributing to the reduction of harm that young people engage in and that ultimately may lead to suicide, we’ll be very much supporting that,” he said.

Labor had also pledged $30 million towards social and emotional wellbeing — a holistic way of looking at mental health, common in Aboriginal health services — in three high risk regions, as well as various welfare and justice initiatives aimed at reducing punitive measures and taking pressure off families, Dodson said.

The Coalition has pledged $19.6 million for Indigenous suicide prevention measures including mental health first aid training to communities and youth, and community led initiatives across the Kimberley, along with investing in mental health for the wider community via headspace.

“If governments funded at a level they should be funding, they’d be spending in the hundreds of millions each year and more likely in the billions each year,” Georgatos says.

He criticised spending money on research, saying governments were spending to “be seen to be doing things”, and said funding should come out of the defence budget.

“The money is there. It’s about deciding what’s more important. War planes? Submarines? Or people’s lives? That’s the decision we need to make.”

Now that Cockie has a car, she drives to Fremantle on Sundays to visit Linda’s grave. Other members of her family are buried there, and she usually sits down for a couple of hours to talk to them all.

Her grief is still overwhelming, but it has also evolved as she has learnt to live without her daughter. She knows that Linda is gone, and yet she feels that she is with her, all the time, as a spirit.

“But I don’t want her here as a spirit,” she says. “I want her here as a person, you know?”

When Cockie was pregnant with Carmel, health nurses named her a “rainbow baby” — a term for children who arrive after the loss of another. It is most commonly used by parents who go through miscarriages or stillbirths, but for Carmel, it’s apt.

“When one goes and another comes, she’s a rainbow child,” Cockie says. “That’s the name for her.”

Carmel has three given names. All of them are for women in Cockie’s life — the people who kept her going through nine months of pregnancy following the crushing loss of Linda.

“They’ve been my three big supports,” Cockie says. “So I had another girl, and I put her role models there, to have a strong name for her.”

One of those women, and one of Carmel’s two middle names, is Megan.

Krakouer smiles down at her namesake. “She’s pretty special, hey?”

If you or someone you know needs help, you can call Lifeline Australia on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue Australia on 1300 22 4636. The NICRS can be contacted on 1800 805 801.