MINNEAPOLIS — The effects of the global pandemic rolled out like a series of gut punches for Brianna Phillips, 16, and her family.

When Minnesota’s governor shut down the state on March 27 to curb the spread of the coronavirus, Brianna couldn’t see her friends and was no longer able to do the things she’s most passionate about — like campaigning for an organization that spreads awareness about sexual health.

She also saw how the coronavirus hurt one family member after another: Brianna’s aunt’s father contracted it and is on a ventilator. The same aunt and her grandmother both lost their jobs due to the ensuing economic crisis. Her mother, Victoria, who is a manager at a local Lowe’s store, told Brianna stories of staff pleading for more hours after losing their other jobs, and of having to keep everyone calm while herself being worried about the virus.

And then came George Floyd. The 46-year-old’s killing in police custody was just the latest reminder of the racism faced by Black people — and exposed the Twin Cities’ inequalities to the world.

In Minneapolis, Black people own fewer homes, earn less, and are less likely to graduate high school than their white counterparts, as Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz was forced to admit in the days following protests in the Land of 10,000 Lakes.

“We rank near the top on personal incomes, on homeownership, on life expectancies,” Walz said. “But if you take a deeper look … all of those statistics are true if you’re white. If you’re not, we ranked near the bottom.”

Brianna couldn’t escape mentions of Floyd on Facebook. The video of his death spread like wildfire online, sparking heated debates. As part of the generation that grew up seeing footage of Black deaths going viral, Brianna knew there were going to be massive protests fueled by people who had grown tired of seeing yet another man killed by police.

Brianna’s mother, Victoria, was at work on May 25 when her own mother called her about “that guy from your neighborhood in the news,” and took a short break to watch the video. She immediately thought about her kids. How would she talk to them about this without traumatizing them? How could she teach them what this moment meant? How could she help them navigate the news and what it meant to be Black in America? But she kept her feelings to herself, pretending “like I’m not hurting.” For a long time, Victoria had learned to “dim” herself and “blend in” when she’s one of a few Black people at work. This moment was no different.

Brianna, her mother, her father, Montez, and her other two siblings came together that night the video went viral. Brianna and her 12-year-old sister, Alecia, were scrolling through Facebook, sharing the latest news reports with each other while their mother told them she was sorry she couldn’t shield them from this reality. Alecia felt physically ill from the stress. Brianna’s 16-year-old brother, Jonathan, was frustrated but mostly said it made him “so tired.” And while Brianna’s father was clearly passionate about Floyd’s death, he hadn't yet told them how he feels about it, she said.

They were all in shock, Brianna said, and hadn't worked out what they felt and thought. But they knew instinctively it was going to be different from the deaths of other Black men, like Philando Castile in Falcon Heights or Jamar Clark in Minneapolis.

The more the family of five learned about George Floyd, a man who was active in his community and was known as a “gentle giant,” the more they felt like his death would be the “straw that broke the camel’s back,” said Victoria. There was going to be an “explosion of anger,” Brianna said.

To Brianna and her mother, Floyd’s death was significant far beyond the details of the case: It immediately invoked the injustices the family had seen through the generations that have only been amplified in recent weeks.

There were the numbers showing that Black people were dying of COVID-19 at outsize rates across the US. There were the stories about minority-owned small businesses not receiving the government loans they needed to stay afloat. There was the fact that in coronavirus epicenters, like New York City, essential workers are disproportionately Black and people of color. And the long-standing issues, such as Black workers making less than their white counterparts, having much less wealth to their name than white households, and having a history of being mistreated by the healthcare system.

Add to these inequities the recent killings of Black people: Ahmaud Arbery who was killed by white men while jogging, Breonna Taylor who was shot by police in her home, and then Floyd who was killed in police custody after someone reported that he was using a counterfeit $20 bill. Meanwhile, white protesters disobey national lockdown rules in Michigan without being harmed by police.

While the president and many media outlets have looked at the protests in the Twin Cities as violent spectacles, local residents who marched for days after Floyd’s death have repeatedly made it clear that what they want is for lawmakers to hear this message: Systemic inequalities have plagued Black Americans for way too long, and radical change is needed.

Victoria has had to swim against these currents long before the governor publicly acknowledged them. As a child, her parents depended heavily on free school meals, and she remembers growing up with very little. But she wanted more for her daughter and worked hard to afford Brianna the kinds of opportunities she had been denied. Victoria became the first member of her family to go to college and fought her way into the kind of managerial position at Lowe’s that few Black women hold.

For the past few years, she thought her work would pay off, that her daughter would be fine, but Floyd’s death crushed that hope.

“I felt at ease and almost relaxed,” Victoria said about Brianna’s future. “And now I almost regret that.”

While these recent events have made Brianna and her siblings anxious, it has also given them some kind of resolve. “My generation is definitely more aggressive” about these issues, Brianna said. “I’m going to fight this, not just for me, but also for my parents. They have gone through this for years and things should be better now.”

These teens think in isms

When Alejandro Anderson, 17, saw the video of Floyd, his reaction was similar to Brianna’s. He didn't just see police brutality, he also saw the racial inequalities that have long plagued Black communities in the Twin Cities.

And Alejandro isn’t wrong. A recent study of census data ranked the Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Bloomington metropolitan area as the fourth-worst place in the country for Black people to live in. The NAACP published a report last year detailing how Minnesota is home to “some of the greatest racial disparities for African Americans people in the Country.” Homeownership among Black people was 25.4% versus 75.3% for white residents, nationwide those figures are 44% versus 73% respectively. The median income of Black residents was just 43.4% of that of white residents, nationally that that number is about 61%. At the statewide level in 2019, 70% of Black students in Minnesota graduated from high school compared to 89% of their white counterparts.

A study of 100 metropolitan areas in the US by the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program found that the Twin Cities ranked 92 when it came to racial inclusion.

This is in stark contrast to the narrative touted by several publications that the Twin Cities is one of the best places to live, making it particularly popular among “techies” in recent years. The Brookings study also found the cities’ track record on racial inclusion to be one of the worst in the country — while also ranking it the 26th best-performing metropolitan area when it came to economic growth.

This is a harsh reality that elected Minnesota officials have now had to confront after years of painting a rosy picture.

“You cannot continue to say you’re a great place to live if your neighbor, because of the color of their skin, doesn’t have that same opportunity. And that will manifest itself in things that are the small hidden racisms,” Gov. Walz said. “The ultimate end of that type of behavior is the ability to believe that you can murder a Black man in public.”

There are places around the city that display these chasms between minority neighborhoods and more affluent whiter ones.

There’s a house riddled with bullet holes and broken windows in a neighborhood near Alejandro’s home where Minneapolis police killed Chiasher Fong Vue, a man from the Hmong ethnic minority, firing more than 100 rounds after responding to a domestic disturbance incident. The home sits in a predominantly Black neighborhood in north Minneapolis where a lot of minority homeowners lost generations of wealth due to the 2006 housing bust. Alejandro’s mother, Stephanie Gasca, bought a foreclosed home down the street in 2009.

Next door to Vue’s former home is one that was built in 2020, currently listed for $269,900 on Zillow. That’s roughly $100,000 more than what Vue’s home sold for in 2018. Zillow estimates the average home value in the neighborhood to be about $185,000.

Then there’s the 4th Precinct in Minneapolis, which sits on the grounds of what was once a community center for Black activists called The Way. Verlena Matey-Keke, 76, one of the center’s cofounders, told BuzzFeed News The Way was created in 1966 at the height of the civil rights movement as an effort to “address the oppression and it came about as a relief for the pent up rage” felt by Black people in Minneapolis. The center’s organizers provided classes in African American history, a theater, and free practice rooms where musicians like Prince once rehearsed.

But The Way was shuttered in the mid-1980s and a few years later was replaced by the police precinct, which now stands tall amid other Black institutions like the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and the north branch of the NAACP. Matey-Keke said the precinct’s choice of location felt like “their attempt ... to erase us.”

“Even as of today, the issues have not been addressed and it is white supremacy,” said Matey-Keke. “We don’t talk about the historical trauma that Black people have gone through. We’re not just beginning in the ‘60s, and it’s what’s set it off last week. And it wasn’t new in the 1960s.”

She said she’s waiting to see what will happen after the protests die down because “we’ve been here before.”

“I’m waiting to see what the outcome is. I’m waiting for the follow-up,” she said. But she was also heartened by the international outpouring of support for the Black community. “If our existence tells us nothing else, it tells us that you cannot kill the human spirit.”

All of these inequalities play a role in how poor Black communities are seen and treated by law enforcement, Alejandro said.

“Everything for people of color takes more steps, so that leads to poverty, which leads to more crime,” Alejandro said. “Then the police come here and they feel like it’s more important to stop crimes than it is to protect people. They would rather have law and order than real peace.”

For young adults like Alejandro, these inequalities are deeply felt. He attended a school with mostly white instructors in the suburbs where a teacher kicked him in front of other students for laughing in class. It wasn’t the first time the teacher had done it, and it was always to students of color, Alejandro said. The teacher wasn’t removed from the class or investigated until his mother pushed the school to address the issue. Alejandro later went to a mostly Black school where he remembers the school menu consisting of chicken sandwiches and burgers for several months.

Closing the education gap is key to ending racial disparities, said Alejandro. In the state of Minnesota, Black children graduate at a rate of 69.9%, while white children graduate at 88.65%. But Alejandro believes it’s not a priority for people in positions of power, who are mostly white. It’s easier to convince uneducated people that there’s nothing wrong, or hope people of color don't realize there’s something amiss, he said.

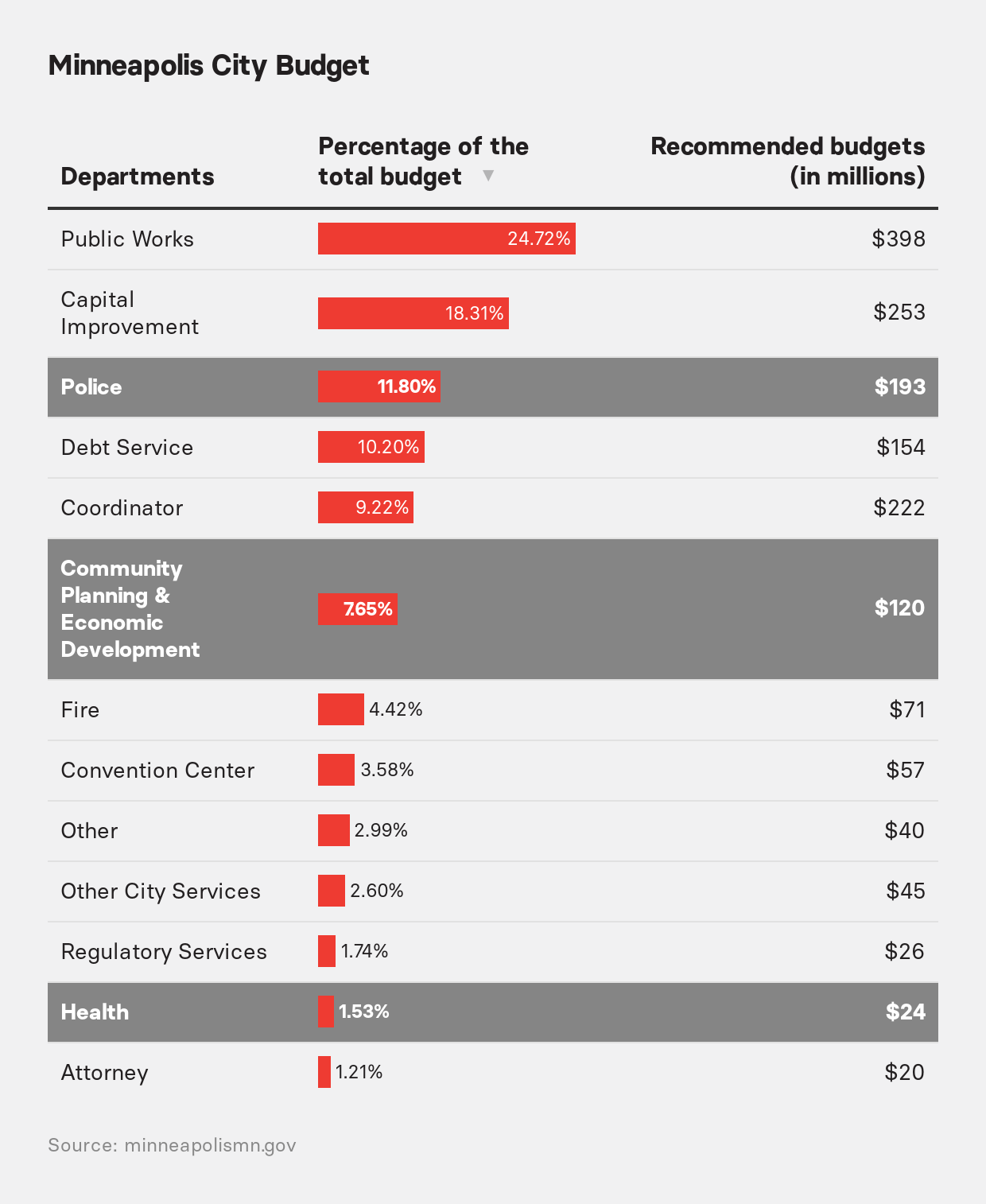

Alejandro’s view is reflected in some of the local government’s spending. The city of Minneapolis, for instance, spends 11.8% of its entire budget on the police department, more than it does on departments that provide public housing or training for low-income workers.

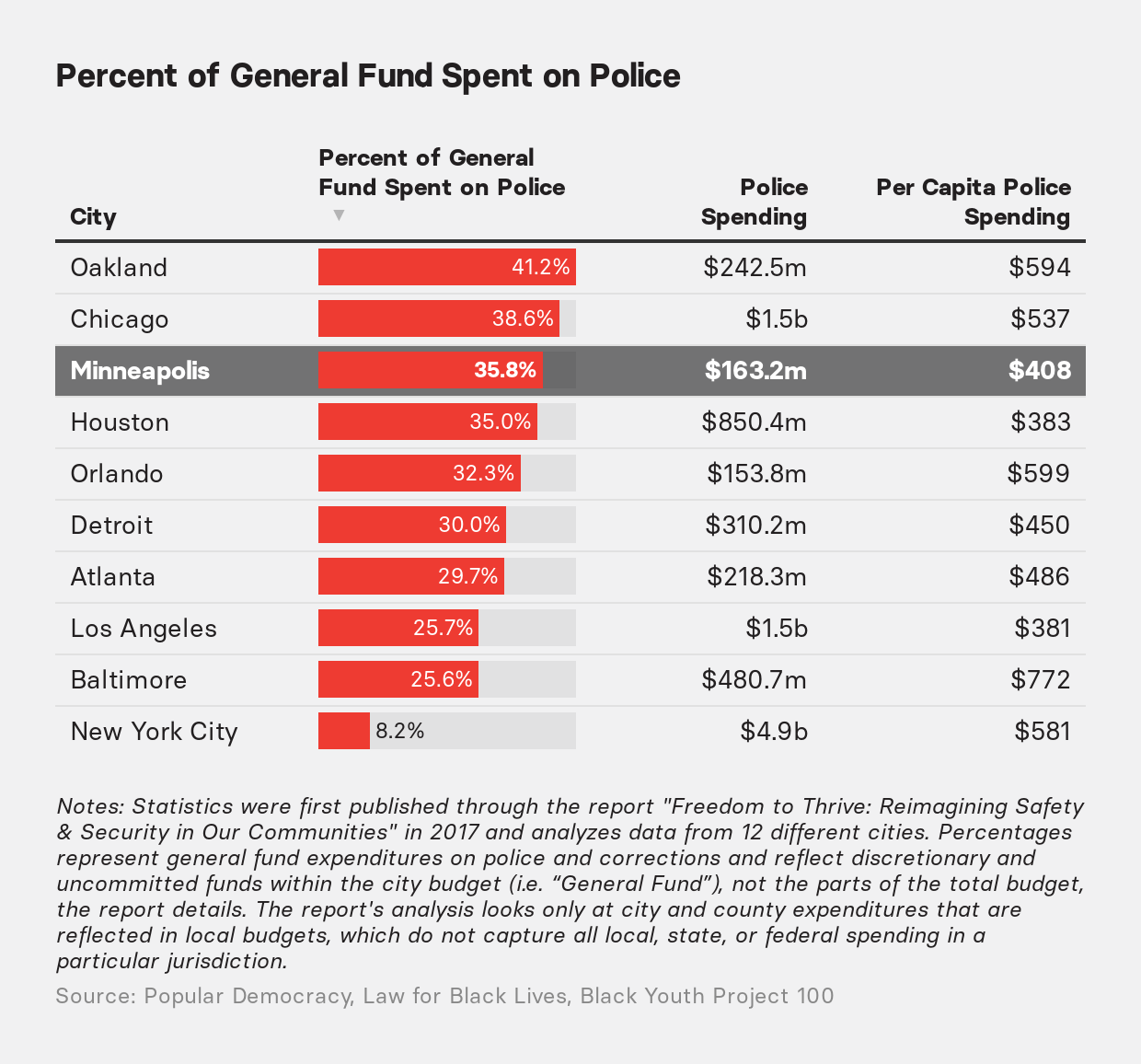

A 2017 study found that the city spent 35% of its general fund — meaning the part of a city’s overall budget that leaders can spend at their discretion — on police.

These are the kinds of decisions that have left young people having to fight for their rights while also trying to figure out who they are as an adult. For a generation that was born around 9/11 and formed its first memories during the 2008 economic crisis, fear of imminent doom seems to be the norm. But it’s also made some of them proactive and vocal.

During a recent march from the governor’s residence to the Minnesota state capitol, the crowds were filled with young folks, chanting Floyd’s name. 21-year-old Sierra Winge said: “We were all traumatized by the video of George Floyd’s death but we’re all still here [protesting]. That says something.”

Mayah Varnado, 21, of St. Paul marched alongside Winge on June 1, as she had for days after Floyd’s death. Varnado said she had been coming out to protest police brutality since she was 15 with her sister.

“It’s just ridiculous. Why am I still out here protesting the same thing?” Varnado said. “This has been happening and will continue to happen if we don't keep chipping away at the iceberg.”

Alejandro himself was no stranger to protest — his mother would regularly take them to demonstrations when she worked as an organizer for the Center for Workers United in the Struggle, down the block from where Floyd was killed. They also attended protests against police and vigilante violence, starting at the University of Minnesota following the 2012 death of Trayvon Martin.

But last week was the first time Alejandro told his parents he wanted to go.

“There was no way I wasn’t going to go,” Alejandro said. “I wasn’t going to sit on the sidelines.”

His 11-year-old sister, Kennedy, is similarly drawn to the worldwide debate sparked by Floyd’s death. Unwilling to wait for her parents to bring up the issue, Kennedy demanded they hold a family meeting last week after she saw people on the news discussing the looting and fires in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

“This morning I heard my 11-year-old having a conversation with one of her teachers who was asking if they think violence is necessary,” Stephanie Gasca told BuzzFeed News. “She said, ‘Well, Black people have been peaceful for a long time and it's not working.’”

In Minneapolis’s north side, students are leading the fight to rename a local school that was named after Patrick Henry, an enslaver. The Midwest Center for School Transformation and the Twin Cities Innovation Alliance raised more than $26,000 in less than 10 days to help a youth-led program for “healing conversations about the murder of George Floyd and the compounding conditions of race, white supremacy and injustice in the Twin Cities.”

“Our young people are like, ‘We want to look forward,’” said Marika Pfefferkorn, an organizer who has been working with young people in the Twin Cities for years. “We don’t want to react to this moment because that is what has been happening.”

One of the blessings of being young is you're not as jaded, Alejandro said.

“Once you get older and things have always been that way, you lose hope — like it is what it is,” Alejandro said. “But kids always look for the bright spots. They always think of how things can get better, and kids are the reason people still have hope.”

A potential for change

Some of these students grow into local leaders at an early age, like Christian McCleary, 24, who works to bring GED and ESL classes to refugees, and to educate young Black men. He’s been an activist since he was 15 and is now hoping to run for city council in the town of Apple Valley.

For him, the issue is not about the police in isolation — it’s about having too many police officers while less money is spent on other services.

This moment is bigger than just George Floyd, he said: He wants the attention Floyd’s death brought to Minnesota to lead to more cultural competency training for officers and bring about important conversations.

On Sunday, a veto-proof majority of the city council vowed to disband the Minneapolis Police Department and redirect funds to a new public safety system.

Wynfred Russell, 46, a council member in Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, echoed these sentiments. The former professor, who is an immigrant from Liberia, was part of the “blue wave” during the 2018 midterm elections, when many government seats were filled with first-time Democratic politicians.

“The opportunity that I see is for us to come to the table. It’s not the time to come and say, ‘I’m not racist, I have Black friends,’ but it’s the time for us to come here and boldly make people uncomfortable,” said.

“Let’s look at what it means to be in a ‘safe city’? Does that mean that we have to have more police officers than teachers or nurses? What does it mean to have a ‘safe community’?”