Katy Perry is in a bedroom, wearing lingerie, and caterwauling about kissing a girl and liking it. Despite being surrounded by a gaggle of attractive women in underthings, Perry is unfazed. Her flirty gaze remains locked on her most sincere interest — the camera — and she doesn’t bother to touch, kiss, or even acknowledge the women around her. She’s just curious, playing an experimental game — she doesn’t need to know the girl’s name, it’s not what good girls do, not how they should behave, she’s confused, it feels so wrong and so right, it don’t mean she’s in love tonight, it ain’t no big deal, it’s innoceeeeeeeeennnnnnnt, and, oh yeah, she hopes her boyfriend don’t mind it.

Perry’s 2008 smash hit “I Kissed a Girl” capitalized on fauxmosexuality, a trend in which heteronormatively feminine, straight-identified artists say or do queer things to acquire edge, attention, views, money, social relevance, and the validation of the male gaze. Starting with the Madonna–Britney/Madonna–Christina kiss at MTV’s 2003 Video Music Awards, this strategy accelerated with “I Kissed a Girl” and quickly proliferated throughout mainstream performances including Shakira feat. Rihanna’s “Can't Remember to Forget You”, Jennifer Lopez feat. Iggy Azalea’s “Booty”, Nicki Minaj’s “Anaconda,” and even Little Big Town’s queerbaiting “Girl Crush.”

Whether stars are showing, telling, or both, the politics of representation are tricky in 2018.

These songs and their accompanying videos tapped into male fantasies and secured considerable attention (2.24 billion views combined), but the artists never stopped winking at the audience, making their same-gender interactions and attractions look cheesy and fake. Such strategic productions prevented more nuanced and sincere ideas about queer women’s pleasure, sensuality, and eroticism from entering the mainstream, rendering queer love invisible and offering straight, saccharine substitutes as stand-ins for the real thing.

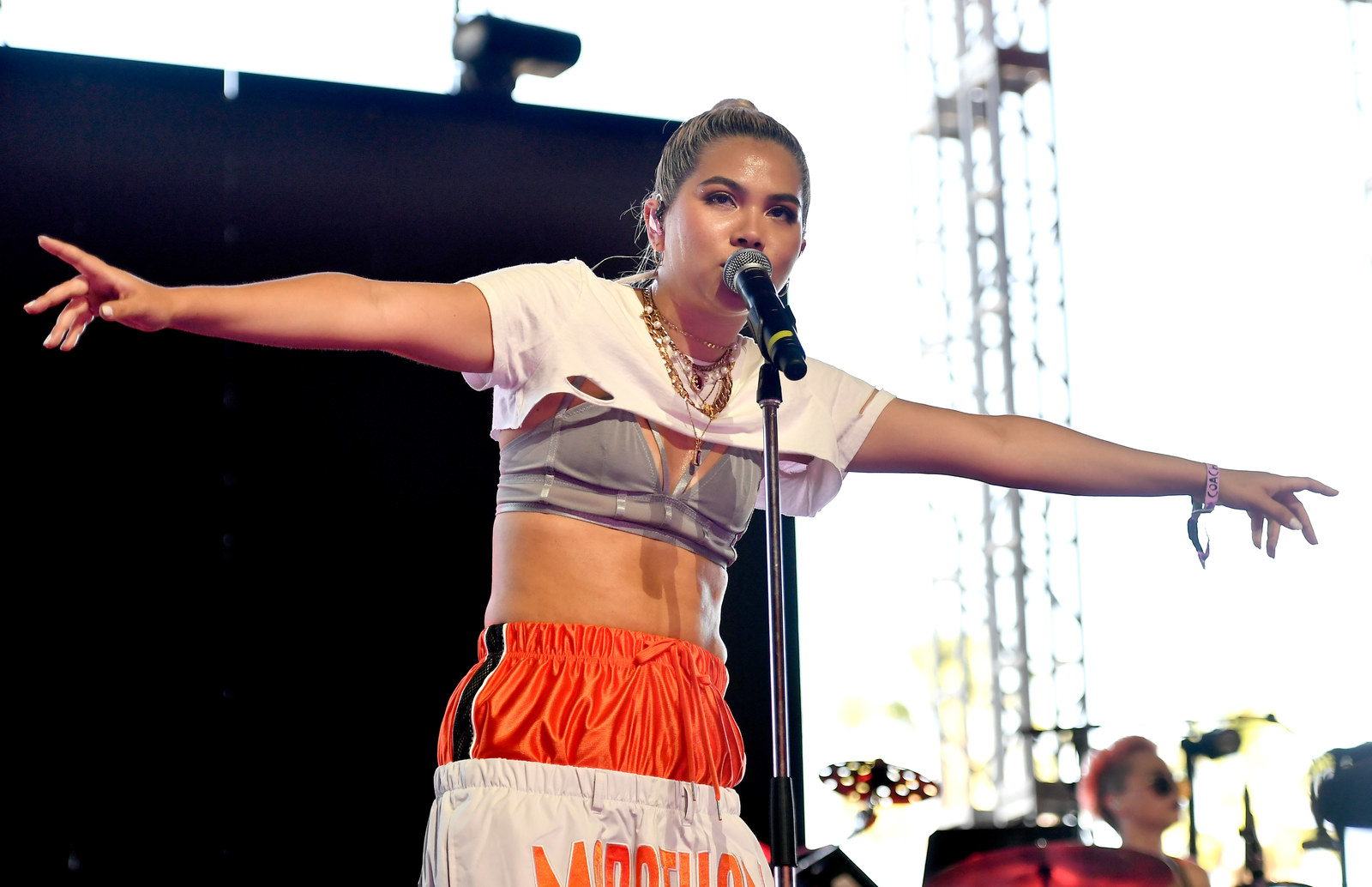

But while these straight artists in the foreground peddled fiction, queer artists seeking more authentic representation built their ranks. Now, at least 13 stars with considerable followings — Janelle Monáe, Hayley Kiyoko, Halsey, Miley Cyrus, Lady Gaga, Tegan and Sara, Demi Lovato, Lauren Jauregui, Kesha, Sia, Kehlani, and Rita Ora — have come out as lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, or queer, providing greater visibility for the diverse range of LGBT identities. St. Vincent and others reject titles but have also enjoyed high-visibility same-gender relationships. File under: show, don’t tell.

Whether stars are showing, telling, or both, the politics of representation are tricky in 2018. There’s more queer representation among pop stars than ever before, with not one, two, or three of them shouldering the burden of getting all manner of queer representation just right. But this expanded representation comes with new challenges and expectations. Now, queer pop stars tend to be believed when they come out, which is progress, but after they do, they face scrutiny from queer audiences eager to pit them against one other to establish who’s the wokest and the queerest. These self-defeating contests ultimately disempower artists, divide the community, and threaten to constrict our representational reach and power at a time when it is finally expanding in the mainstream.

Sexuality is personal, and a charged subject for artists on the world stage to discuss, share, or promote — especially when it deviates from established industry norms. With so many similar stories entering the public consciousness at the same time, the frames are finally shifting, laying the groundwork for more nuanced, queer, and interesting expressions of women's sexuality that focus more directly on their own pleasure than on industry demands and expectations. Fauxmosexuality may finally be on its way out, but now, rather than (rightfully) excoriating Katy Perry for faking it, we’re chastising queer artists for not being believably, consistently, or academically queer enough.

Rather than rigidly policing or outright canceling stars who appear to contradict our individual notions of queerness, we might instead opt to celebrate this rich, representational moment, learn more about the wide array of people representing the community in #20gayteen, and encourage young artists, often new to the politics of queerness and representation, to negotiate their individual identities in ways that feel right for them.

Each star has her own path, and her own story — some messier than others.

To sidestep questions about her gender presentation and romantic attachments, Janelle Monáe debuted as an android in her first video, “Many Moons,” in 2008, and maintained the persona for a decade: She was an android, and she only dated other androids. But still, by incorporating the relentless performance energy and dance moves of James Brown and Michael Jackson (see “Tightrope” and “Many Moons”), often while rocking tuxedos, Monáe’s gender-bending performances were extremely and delightfully queer.

By mastering the masculine/androgynous poses popularized by male stars, Monáe offered audiences something familiar and something queer at the same time — a safe and winning formula. She showed us she could literally be anyone she wanted to be — except, perhaps, herself. Along the way, she gave fans enough hints to crack the code to her sexuality without putting her android act in jeopardy. These indicators came in the form of lyrical questions — “Am I a freak because I love watching Mary?”; visual gestures (as she’s swarmed by adoring women in “Dance Apocalyptic,” she winks at us); and coquettish observations: “Pynk is my favorite part.”

Monáe formally came out earlier this year, after a decade of teasing her knowing fandroids with queer signifiers, double entendres, and nonverbal cues. The is-she-or-isn’t-she intrigue was fun, but it was also frustrating for some fans and writers who had long suspected Monáe was queer, and wanted to celebrate that part of her identity publicly. Music industry insiders used to caution that coming out of the gate as a queer artist was the kiss of death, as forever forward that artist would be known as “the gay artist,” eclipsing all other meaningful differentiators, including musical talent. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons Monáe played it so cautious when disclosing her sexuality. (There are also indications in Monáe’s songs — and interviews — that she felt limited by labels, and worried about being rejected by members of her family, her community, and her God for her differential “programming.”) By the time Monáe came out, other stars had already paved the path, exposing audiences to a variety of nuanced coming-out stories and all but ensuring a soft landing for her, at least where media outlets were concerned.

Music industry insiders used to caution that coming out of the gate as a queer artist was the kiss of death.

Monáe ultimately dropped the android act to reveal her powerful-with-a-little-bit-of-tender self in an interview with the Guardian. In February 2018, she stated her desire to “focus on being a complete, complex human being,” noting: “I don’t know who’s gonna come with me and who’s gonna criticise me, but I’m not gonna renege, and I’m not gonna hide.” Two months later, Monáe was profiled in the New York Times Magazine, where she discussed gender and sexuality but wouldn’t get too personal. Days later, Monáe officially came out to Rolling Stone as a “queer black woman” who had “been in relationships with both men and women.” She indicated she had initially identified as bisexual but now identifies with pansexuality as well. Her story spread quickly and widely, with no questions asked — except whether she was romantically involved with actor Tessa Thompson. (This stood in stark contrast to the questions and doubts Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus faced when they came out as bisexual and pansexual, in 2009 and 2015, respectively.)

Now, as a credible and compelling “free-ass motherfucker,” Monáe is not only timeless, but timely: the embodiment of what inclusive, intersectional, pop star representation can look like in 2018. Monáe’s queer, futuristic gaze, evident in her “emotion pictures,” is refreshingly diverse, erotic, and real. Prince’s influence permeates every dimension of “Make Me Feel,” from its overall sound, to the bisexual lighting in the song’s video, to the flirty, dirty, intentional ways the mostly androgynous cast interacts. As the video winds down, Monáe races back and forth between love interests of different genders, declaring: “Good God. I can’t help it. Hey — that’s just the way that I feel.”

Although Hayley Kiyoko also worried about disclosing her sexuality prior to releasing her breakthrough single, “Girls Like Girls” (~just like boys do, nothing new~) in 2015, she leaned into her fear, making her sexuality an essential part of her brand and her music. This strategy arguably expanded her appeal rather than limiting it, with Kiyoko quickly becoming a sacred figure, exalted as “Lesbian Jesus.” She now embraces the role, making her lesbian identity and love of women central pillars of her most popular songs and videos. These videos have resonated widely, with six individual songs — “Girls Like Girls,” “Cliff's Edge,” “Sleepover,” “Feelings,” “Curious,” and “What I Need,” garnering between 12 million and 97 million views apiece on YouTube. (Kiyoko’s warm reception has also made it more imaginable for others — King Princess among them — to begin their careers open about their sexuality.)

Beyond surface-level representation, Kiyoko’s videos offer charming, open displays of love and desire between women, without minimizing the inherent vulnerability of such pursuits, or the potential for betrayal and heartbreak. Kiyoko’s protagonists gaze at each other, communicating their vulnerability, attraction, and intent through hidden looks, provocative dances, and intimate interludes that prioritize their pleasure over the pressures of the male gaze. Kiyoko’s appeal is powerfully unconventional, too, for its tomboy-next-door-ishness. Her dancing is athletic, full of swag; her dress is basic (jeans or track pants, T-shirts, and sneakers), with a little flair (Hawaiian shirts); her lyrics, queer in their own right, explore all the lesbian feelings (“I overcommunicate and feel too much”) and insecurities (“I’m just curious, is it serious?”). All she needs, she says, is “a girl who ain’t afraid to love me,” ’cause she “ain’t putting on a show.”

When Kiyoko was younger and negotiating her own queerness, she drew inspiration from an unlikely source: Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl.” Although the song read as a representational betrayal to queer fans who were seeking something more legitimate based on the promise of the title, it landed differently on Kiyoko. “It was a very exciting moment,” she told the Guardian. “Of course, I wished that it was a gay girl singing, but I was like, ‘That’s gonna be me.’” Despite the song’s well-established limitations, Kiyoko recognized enough of herself in its lyrics to want more, for herself and for her audience. And Lesbian Jesus delivered, mightily.

While Monáe and Kiyoko have dominated queer music headlines in 2018, it was Halsey, who is bisexual and biracial, who boldly pivoted from using gender-neutral pronouns to using same-gender pronouns on “Strangers,” a track featuring Fifth Harmony’s Lauren Jauregui, who is also bisexual, in 2017. (Halsey told Vulture she was asked to consider collaborating with Katy Perry but responded she wouldn’t do the track with an artist “unless they’re fucking gay.”) Halsey made this strategic move — a conscious effort, she said, to “be a better representative of the LGBT community” — and then doubled down on it, opening the track with the line “She doesn’t kiss me on the mouth anymore.” (This explicit queerness was striking and unprecedented coming from such a prominent queer artist. Halsey has 9.76 million Twitter followers, and her official solo videos have collected approximately 500,000,000 views, while her guest appearances with the Chainsmokers and G-Eazy bring her collective video views to more than a billion.) Her follow-up single to “Strangers,” “Bad at Love,” continued her trajectory, showcasing the diversity of Halsey’s romantic spectrum as she recalled two straight relationships before landing upon the one who got away — a woman.

In 2018, Halsey received the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Music Artist. In her acceptance video, she articulated her struggle for visibility and acceptance: “I’m a young, bisexual woman, and I’ve spent a large part of my life trying to validate myself — to my friends, to my family, to myself — trying to prove that who I love and the way that I feel is not a phase, it’s not part of some confusion that’s going to change or could be manipulated.”

Monáe, Kiyoko, and Halsey’s stories resonated deeply with fans, who showed them much love, admiration, and support on social media. This response may be attributable to the artists’ genuine connections with their fans, the perceived authenticity of the artists’ representations of their queerness, their level of success when they came out, and rapidly changing times. Two more-established pop stars — Miley Cyrus and Lady Gaga — were met with more skepticism when they came out as pansexual and bisexual, respectively, and both continue to struggle with perceptions that they aren’t authentic enough or consistent enough in the way they talk about and express their sexuality. Perhaps their stories demonstrate that more prominent stars have a more difficult time being accepted as LGBT, which may be a function of the audience’s fauxmosexual conditioning and top stars’ need to build dynamic platforms based on provocation, which can compromise their believability.

In late 2014, Miley Cyrus founded the Happy Hippie Foundation, an organization designed to support homeless youth — particularly LGBT-identified homeless youth — and other vulnerable populations. Cyrus also came out in 2015, telling Elle UK, “I’m very open about it — I’m pansexual,” and the Guardian, “I don’t relate to being a boy or girl, and I don’t have to have my partner relate to boy or girl.” But because Cyrus’s penchant for shock value was already high — perhaps because she was only 22 and in the midst of a massive image overhaul — and because she had already been accused repeatedly of appropriating hip-hop culture and black aesthetics to spice up her act in the Bangerz era, Cyrus’s news was met with suspicion. But to her credit, Cyrus publicly embraced a pansexual and genderfluid identity before most people knew what those words meant.

While some have dismissed Cyrus’s gender identity and sexuality as a phase — another attempted appropriation — citing “Malibu” as evidence of her return to good-girl heteronormativity — a deeper consideration of the songs on her most recent album reveals queerer dimensions. Her second video, “Younger Now,” finds her in drag, channeling Johnny Cash and Elvis Presley, “She's Not Him” chronicles a bittersweet, nuanced breakup with a woman, and “Rainbowland,” performed with godmother Dolly Parton, speaks for itself: “It's the only thought I think, you know where I stand / I believe we can start living in a Rainbowland.”

Lady Gaga’s recent caginess about her identity has also compromised her credibility with some LGBT writers and fans. Gaga came out as bisexual in a 2009 interview with Barbara Walters, and in 2013, tired of explaining herself, she told Attitude: “I mean, I am bisexual, I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again. ... I’m sorry if this is a bit vulgar — but I don’t need to eat pussy in front of the whole world for people to take me seriously.” One year later, an Advocate headline questioned whether Gaga had lost her sizzle — and lost the gays. Similar questions arose last year after Gaga told contestants on RuPaul’s Drag Race: Untucked that she was “not a gay woman” (she has never claimed to be), causing speculation in the Advocate and elsewhere that she was backpedaling, retreating from bisexual to ally.

Some might ask why Gaga didn’t just keep coming out. The better question is: Why should she have to?

But when Lady Gaga — who has arguably done more for LGBT visibility and LGBT rights than any queer woman artist before her — isn’t consistent enough, or queer enough, for LGBT music writers and fans, how prohibitive are our standards? Earlier this year, Brian O’Flynn, writing for the Guardian, celebrated Gaga’s contributions to LGBT culture over the past decade, calling her “the background music in every gay club,” the overture to every drunken kiss,” and “a talking point for every first date.” He then made an observation we would be wise to remember and acknowledge: “Lady Gaga queered the mainstream.”

Some might ask why Gaga didn’t just keep coming out. The better question is: Why should she have to? Her long history of actions should speak for themselves at this point. She may simply have explanation fatigue, a product of coming out repeatedly and still being doubted due to the antics of her fauxmosexual peers, rampant biphobia, and the presumption that she will say anything to be provocative. Sounding like a strong and committed ally might simply be the least exhausting way of advocating for queer people without being faced with constant speculation and disbelief.

Whether their coming-out has been smooth or bumpy, joyous or fraught, these current artists also owe a debt of gratitude to the breakthrough artists of the late 1980s and early 1990s, who provided LGBT audiences with a similar representational moment 25 years ago. That movement was powerful but short-lived, and is thus instructive for the position we find ourselves in now.

Melissa Etheridge became the most prominent lesbian in popular music with the album — and the declaration — Yes I Am in 1993, the same year k.d. lang won the Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for “Constant Craving.” In the period between 1987 and 1994, Etheridge scored two multiplatinum albums and two platinum albums; the Indigo Girls tallied one multiplatinum album, two platinum albums, and two gold albums; and lang sold multiplatinum once and gold twice. Although sales are no longer the best indicators of popularity, big numbers then indicated that these artists were popular enough to maintain mainstream careers.

Whether their coming-out has been smooth or bumpy, joyous or fraught, these current artists also owe a debt of gratitude to the breakthrough artists of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

As these women captured mainstream audiences, independent acts like the bi-identified Ani DiFranco, who just released her nineteenth studio album, Binary, in 2017, found peace at the indie level, where most long-lasting, music-centered careers for women are built and sustained. (Courtney Barnett and Princess Nokia arguably occupy a similar kind of influential-but-indie queer space now.)

Encouragingly, the queer women fighting for visibility in popular music today inhabit more fluid and intersectional identities than ever before, enabling this moment to be more nuanced and inclusive. (Monáe is black and pansexual; Kiyoko is Asian American and a lesbian; Halsey is biracial and bisexual, and Cyrus is pansexual and genderfluid.) All offer aspirational visions of multilayered identities and embodied eroticism that provide queer people with more authentic representation via distinctly queer surrogates — something desperately needed and long overdue.

But for every clear representational victory notched, there’s still confounding mixed messaging coming from newer bisexual and queer stars still negotiating their identities. Earlier this year, Rita Ora and several collaborators released “Girls” to backlash from queer fans and artists. Some disliked the suggestion that she needed to get drunk to kiss women (“red wine and I want to kiss girls, girls, girls”), while others bristled at the crass, predatory lines of collaborator Cardi B: “I steal your bitch, have her down with the scissor.” But rather than invalidating or “canceling” Ora, Kiyoko and Kehlani engaged her in a discussion about representation via Twitter. Kiyoko was concerned Ora and her peers did “more harm than good for the LGBTQ+ community” with the song, and that it fueled “the male gaze while marginalizing the idea of women loving women.”

This was an amazing moment — and one worth modeling in other conversations within the community. Reasonable people can disagree, but they can also give those they disagree with the benefit of the doubt rather than ascribing terrible intentions to them. Kiyoko said she knew it “wasn't the intention of the artists on the song” to minimize her lived identity, but that the lyrics could have been more thoughtfully constructed to avoid such issues. She concluded by stressing, “We can and should do better.”

Kehlani tweeted: “hate to be THAT guy but there were many awkward slurs, quotes, and moments” before stating that she respected all of the artists on the track and would love to work with any of them in the future, but “… there. were. harmful. lyrics. period.”

Such tricky moments can be representational nightmares, reminders that social progress is rarely linear. But they also come with a silver lining. Such misunderstandings and missteps provide us with the opportunity to realize that queer people don’t come preprogrammed with gender and sexuality studies degrees and vocabularies, and that generous allies inside the community can sometimes help those negotiating their identities to see anti-LGBT bias they may have absorbed and reproduced, often unwittingly.

Ora, who identifies as queer, responded to Kiyoko’s and Kehlani’s concerns with her own generosity on Twitter, saying she would never “intentionally cause harm to other LGBTQ+ people or anyone” and that she had been trying to provide an “accurate account of a very real and honest experience” in her life.

There’s no one way to be lesbian, bisexual, or pansexual — and precisely because there isn’t, LGBT audiences have different ideas about whose representations count as authentically queer.

There’s no one way to be lesbian, bisexual, or pansexual — and precisely because there isn’t, LGBT audiences have different ideas about whose representations count as authentically queer. With fauxmosexuality dominating the foreground in recent years, it is not surprising that some younger people establishing their identities at that time — some of them pop stars — internalized some of its lessons (e.g., women only kiss each other when they are drunk, bored, feeling counter-normatively naughty — shhh, don’t tell your mother — or trying to turn a man on). Fauxmosexuality looked gayer than straightness, so it was the most reasonable choice for those who weren’t quite this but not quite that to choose to emulate. (If the only people “coming out” at the top of the industry were straight proxies, it’s heartbreaking, but not surprising, that these stars would serve as queer advisers for listeners and fans until the real thing came along.)

We can glean useful lessons from Kiyoko’s career progression. With Katy Perry as her first representational mentor, Kiyoko’s subsequent learning curve was pretty steep, but she mastered it well enough to quickly become a gifted teacher. Now playing by new rules that she has in large part written, Kiyoko is mentoring colleagues about how to produce thoughtful representation in their work (as on “Girls”) without being obnoxious, and teaching her collaborators how to occupy and own new positions in the industry.

Kehlani’s development as an artist and ally is also instructive. Not long ago, Kehlani exhibited some gender and sexuality blind spots of her own, which she promptly addressed when they were called to her attention. But rather than focusing on what Kehlani did or didn’t know then, we should instead celebrate her growth as an artist — and as an out LGBT figure now — and applaud the representational diversity her collaborations and conversations with other artists will enable in the future. (Kehlani is just 23 years old.)

All of this is to say we should not expect young LGBT pop stars to have the same understandings of LGBT issues as people who have been out and active in the community for years or people who have PhDs in gender, sexuality, or media studies. Some of these young pop stars are new to the industry, the community, and, possibly, the symbols and languages of oppression, and yet we’re expecting them to be polished spokespeople before they’re ready. As they make representational blunders that sting, silence, or betray us, our impulse may be to publicly shame them for their ignorance, but this is often counterproductive, dividing the community from within.

Still, representation is too important — especially in communities where representation is scarce and each individual example speaks volumes — to simply give these stars a pass. Allowing stars to experiment and recover is vital, but these celebrities have to show us that they care — and that they’re willing to learn and grow — for second chances to work. Stars who mock or reject criticism, dig in their heels, or build their brands on misrepresentations and appropriations deserve the full force of our critical fury — stars like Katy Perry, who has been aggressively unrepentant about her numerous and varied representational transgressions for years, but has recently changed her tune ever so slightly, perhaps in an attempt to cash in on wokeness.

If what we really want is better representation, what we really need is productive conversation about it. What’s at stake if we don’t listen to each other, or give each other the space to learn from blind spots and mistakes, is having the promise of a new beginning, squandering it, and then having to rebuild again, from scratch, in 25 years. It would be far more efficient to be good allies to each other — even when we disagree strenuously — than to be rendered invisible again.

As Monáe explained to Glamour: “I always think about the next generation and creating a different blueprint for them. That's my goal: to let them know there's another way.” ●