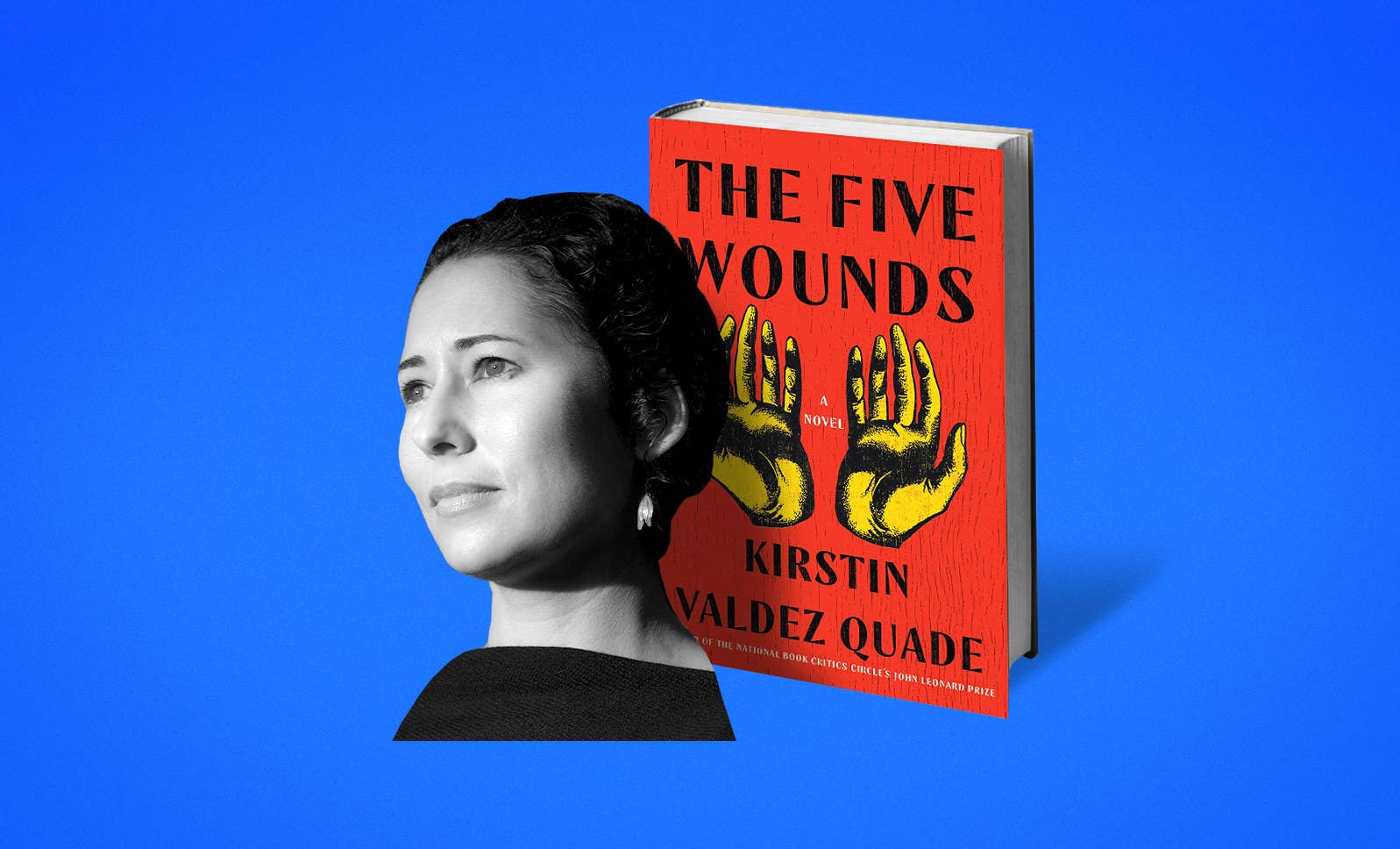

We're so excited to announce Kirstin Valdez Quade's debut novel, The Five Wounds, as the BuzzFeed Book Club June read. The book begins during Holy Week in New Mexico, where Amadeo — an unemployed, mostly absent father who drinks a little too much and lives with his mother — has been given the role of Jesus in the town's Good Friday procession. He sees it as a chance for catharsis. In the excerpt below, Amadeo, tied to the cross, makes the disturbing decision to sacrifice his body (his palms, specifically) to the role. What complicates all of this is the unexpected arrival of his pregnant 15-year-old daughter, Angel, who refuses to give Amadeo's martyrdom the respect he feels it deserves. It's a wholehearted, radiant, and darkly funny exploration of family, faith, and forgiveness.

We're collaborating with W.W. Norton and Libro.fm to give away 10 signed copies and 5 free audiobooks — and, for one lucky winner, a pair of earrings that match the book cover. Enter here!

The hermanos lift the top of the cross, and Amadeo’s vision swings from sky to earth. Upright, his weight returns; his torn heels press into the wooden block. The cross sways as the hermanos anchor it in the hole they’ve dug, packing dirt and stones around the base. Below him, on the distant road, a few glittering cars wink behind the trees, oblivious. He sees distant mesas and pink earth, piñon and chamisa. The air tastes of salt.

Angel stands before him, holding her hands under her belly. The nails, the nails. He is not sure if he says it or thinks it. Tío Tíve looks surprised, but nods and reaches into his pocket for the paper bag. The hermanos pour rubbing alcohol over the wood and Amadeo’s hot hands. The alcohol burns cold and clean.

They hold the tip of the nail against his palm, and he feels it there a moment, light as a coin, and then they pound it through.

The pain is so immediate, so stunningly distilled, that Amadeo’s entire consciousness shrinks around it. He is no longer a man: only reaction, outrage, agony.

He imagined the pain spreading through him like silent fire, unbearable in the most pleasurable of ways, like the burn of muscles pushed to their limits. He imagined the holy expansiveness that would swell in him until he was, finally, good.

But instead there’s only this confused searing clamor, out of which rises a voice he only dimly registers as his own. “The other! Give me the other!” His voice sounds out over the heads of the onlookers, rolls down the slopes of Calvario.

Briefly Amadeo registers dismay in Tío Tíve’s face, and Amadeo is proud of himself, because even though he hurts so bad, he’s about to hurt worse.

In the crowded ER waiting room at Española Valley Regional Hospital, Angel sits beside him in cold silence, flipping angrily though a ragged parenting magazine, while Amadeo cradles his hands in his lap, marveling at the bright stickiness of his own blood soaking the towels. The doctors are taking forever. He’s been sitting under the fluorescent lights in this plastic chair bolted to the floor — leaning forward so as to protect his scourged, tender back — for nearly two hours. Through the automatic doors, the sky is already pink.

“Hey,” he tells a nurse rushing past in scrubs printed with Easter eggs. “How long’s it going to be? Because this is really serious.” He indicates his hands, but the nurse regards him with only the barest tightening flicker around her mouth, then rushes on, consulting her clipboard.

Most of these people don’t even seem sick. Not a single other person is losing blood. Where are the gunshot wounds, the heart attacks, the massive head injuries? Where is the carnage? Would someone please show him a single emergency greater than his own that might explain this unconscionable wait? He is Jesus, for Christ’s sake.

“Whoa,” he tells Angel. “I’m feeling really light-headed.” But she doesn’t even glance at him.

Across from them, a woman scrolls through her phone. Her young daughter — seven, eight— swings her feet restlessly, and a rhinestone-studded flip-flop drops to the teal epoxy floor. With both hands she grips a bag of cherry cough drops. Her eyes are wide and fixed on his bloody towel.

“Are you sick?” he asks the girl as nicely as he can, trying to rein in his annoyance.

The girl raises her eyes from the gore in his lap with some reluctance. Her hair is ratty and she wears a pilled yellow pajama top. “I might have foot-and-mouth disease.”

The mother looks up warily from her phone.

“Maybe I could go before you, then?” Amadeo raises his swaddled hands, shrugging regretfully. “I’m bleeding out.”

“We been here three hours,” the woman says, voice flat, and she returns to her phone.

“You are not bleeding out,” says Angel, louder and meaner than necessary.

But what does she know? Angel is a high school dropout, not a doctor. People die all the time from slit wrists, and the palm is basically the wrist.

He moves in his chair and gasps when the bandage on his back shifts. After the second nail, the hermanos helped him right down and gave him water, offering their congratulations. At first his hands didn’t even hurt — his feet did, from clinging to the block on the cross. Al Martinez had bandaged him up gently. “Keep pressure here and here,” he said, his voice low. “You did good, son.” Still, the man is no professional, and Amadeo can already feel the medical tape coming unstuck.

Would someone please show him a single emergency greater than his own that might explain this unconscionable wait? He is Jesus, for Christ’s sake.

To Amadeo’s surprise, Tío Tíve didn’t show any of the kindness of the other hermanos, didn’t even seem proud. And the old man didn’t call him an ambulance, either, just got one of the hermanos who lives in Española to drop them at the hospital. “Nail gun,” Tío Tíve warned. “You got in the way of a nail gun.”

“Anyway,” says Angel, turning the page of her magazine, “it would serve you right if you did bleed out.”

He looks at her, disbelieving. “Hey. Come on.” What a thing to say. “Where did that come from?”

All of a sudden, he remembers that today is Angel’s birthday. Sixteen. She didn’t mention anything this morning; he wonders if she forgot herself, or if she wanted the day to be his.

“Listen, Angel. I’m sorry you had to be in the emergency room on your birthday. I apologize. Is that your problem? Is that what’s bugging you, that you’re not getting the attention? Listen, I wouldn’t have asked you to come if it wasn’t an emergency. I’m wounded.”

Angel says nothing. Thank god she’ll have the baby soon, Amadeo thinks, because he’s not sure how much more he can take of these moods.

“Did you see the whole thing?” he asks in an undertone. He wishes he’d had her take pictures, but, he reflects, that wouldn’t have been in the spirit of the occasion. Still, he wishes there was a record of his success.

Angel riffles through the magazine too fast to be reading anything. Amadeo watches the article titles as she flips past them: Oral Fixation: Take-Along Snacks Your Child Will Love!; Milking It: Your Toddler and Lactose; I Feel You: Raising Empathetic Children.

Amadeo taps this last article, and Angel pauses her frenetic page-turning. “Hey, that one looks good. Wish I’d known about raising empathetic children.”

Angel gives him a shriveling, disgusted look. “You got to be joking me.”

He turns away from her and looks instead at the television mounted in the corner. Cable news plays too loud. A cruise ship has lost power and is floating free in the Caribbean; the toilets have flooded and the king shrimp have gone off. Big deal, thinks Amadeo. So they get a longer cruise. So they eat Fritos. It’s not like they’re facing a medical situation. It’s not like there is blood involved.

In the corner, a skinny tecato with patchy facial hair clutches himself, shivering and moaning, his eyes squinted as if under full sun. “I’m hurting so bad,” he mumbles to no one. He smells like he’s shit himself. He extends his legs and then draws them in again, shifting on his skinny butt, as if he can’t find a position that doesn’t cause him agony. He’s got las malias, heroin withdrawal, and Amadeo turns away. He thanks God that he can’t stand needles.

Amadeo hurts much worse than after the cutting of the sellos on Ash Wednesday, worse than after those lashes. Earlier, on Calvario, he seemed to have risen to some heightened space that pain didn’t penetrate. He was cloaked in grace, he supposes.

But now he really, truly hurts, and Angel is giving him neither the praise nor the sympathy that he deserves. The pain clusters in his palms, shimmering, ever-changing. The blood is messy, coagulating thick and black, ruining his white pants. He wants, suddenly, to put his daughter in her place. “Don’t you even got a boyfriend?”

Angel turns and looks at him like he’s stupid. “What do you think?”

“Didn’t your mom never teach you not to sleep around?”

“All the girls in my parenting class, not one of them has a guy that matters. Not one. You think you mattered?”

“You shouldn’t have come. You think you have a right to just barge into my house and make yourself at home.”

Angel’s eyes widen, and then she narrows them. “It’s my grandmother’s house. You don’t have a house.” She turns back to her magazine, resolute.

At long last the girl and her mother are called. Amadeo looks at them piteously, and the girl looks back at him with interest, but the mother gathers their things and walks away, refusing eye contact.

“Hey,” he says, ready to reconcile. “Why are you so mad at me? I did good today.”

Angel finally sets the magazine on her lap and turns to him. “So,” she says deliberately, “tell me: What was that? You never said anything about actual nails. You never said anything about actually getting crucified. What good is that to anyone?”

Her words are like a slap. “What’s it to you, Angel?”

Her voice thickens and lowers. “In three weeks, I’m due. Three fucking weeks.” She swallows and turns away, and her eyes rest unseeing on the television. For a moment Amadeo thinks Angel is going to cry. When she turns back, however, her eyes are dry, her face splotchy, gaze shuttered. Very quietly, so quietly he has to lean toward her to hear, Angel says, “How’re you going to hold the baby? Or didn’t you even think of that?” ●

Excerpted from The Five Wounds: A Novel by Kirstin Valdez Quade. Copyright © 2021 by Kirsten Valdez Quade. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Kirstin Valdez Quade is the author of The Five Wounds and Night at the Fiestas, winner of the National Book Critics Circle's John Leonard Prize. She is the recipient of a "5 Under 35" award from the National Book Foundation, the Rome Prize, and the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer's Award. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, The Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories, and elsewhere. Originally from New Mexico, she now lives in New Jersey and teaches at Princeton University.