I’ve been watching the nest cam again. The eaglets hatched and the mother eagle sits atop them and waits, like I wait, for the father eagle to return with a fish. On screen next to the nest cam is a live chat between a biology class and a wildlife expert. Questions appear quicker than the expert can reply to them. A student writes, "Doesn’t look like they made their nest right at all." And it’s true, the nest does seem sort of lopsided. I used to wait for the father because when the mother moved to feed the eaglets it allowed a better look at them, wobbly and covered in gray down. Lately, I’m more interested in the father’s catch. The fish is alive when he drops it into the nest and I imagine the feeling of being plucked from a river by expert talons, pulled from one element into a new one. Air, the first failure of my equipment. I bet it would feel like birth, cruel but important, and while eagles tore at my flesh, I’d be nostalgic not for the water but for the moment I was removed from it, when I flew. How had I not known I could fly? I’d be thinking.

She demands so little of me now — a phone call every two weeks, a card on her birthday, a silencing of past grievances — but I still have a hard time giving it to her.

My mother never told me storks delivered babies but she did say yes when I asked if she’d ever given a blow job. I was eight and didn’t know what a blow job was — I must have overheard the phrase in school and asking if she’d given one (actually, I think I said done not given, had she ever done a blow job) was a way of asking exactly what one was. She never did tell me. For years my proxy definition of blow job was: something my mother has given, something my mother has done. To be perfectly honest the phrase blow job still conjures stubborn memory wisps of my mother. I’m thinking of her now. In the morning she’d ask my sister and me what details we remembered from our dreams, and if we said being trapped in a castle or something, she’d flip through her dream dictionary and interpret what our unconscious minds were hiding, never anything very good. Plus I could tell she left stuff out. As a teenager my sister stopped telling our mother her dreams but I never did. I started telling lies instead.

Whose little boy are you? she used to say when she was tired of me. Her eyes scanning my face without recognition, a menu of foods she didn’t want in a language she didn’t speak. Shouldn’t you go look for your mommy?

I hated that. Whenever I remind her about it she acts like she doesn’t remember. I bring it up more often than I should. My mother calls and we watch the nest cam together, her in Florida, me in California. She demands so little of me now — a phone call every two weeks, a card on her birthday, a silencing of past grievances — but I still have a hard time giving it to her. Talking to her makes me impatient, inversely annoyed with whatever she’s excited about, even the nest cam. She and my sister fought over a dollhouse a few years ago and now my sister calls her that woman and rarely visits her. "I never thought you’d turn out to be the normal one," my mother often tells me.

When I was in elementary school she chaperoned a trip to Blue Springs to visit our class manatee, Randy. For months we wrote him letters, but all he sent were fun facts (Fun Fact! All my teeth are molars!) and autographed photos. "It’s not even his signature," one of my classmates said disgustedly. We were excited anyway. When we arrived the guide pointed to a listless herd of manatees, ancient as dinosaur eggs in the clear water, and asked which was ours. Our teacher told him and the guide said, "Oh, I’m so sorry. Randy died a few nights ago."

He said it with such enthusiasm I thought he was joking. He went on about industrial contaminants and the delicate ecosystem of the spring. Kids who weren’t afraid to cry cried. Others stared at the manatees. For some reason I reached for my mother’s hand and held it. When it became clear that we were just going to hop back on the bus and leave, my mother let go of my hand, stamped over to the guide and said, "You could’ve pointed to any of those fat-ass manatees and said 'there’s Randy' and nobody would’ve known the difference."

"What did we learn on our trip to Blue Springs?" our teacher asked. No one was sure.

I can’t recall if he was defensive or chagrined, but neither he nor the teacher could placate her. Finally she said, "We want a new one. Today. We’re not going anywhere until that happens." The guide left and we sat at picnic tables and ate bag lunches, thinking about Randy and his fun facts. The guide returned a half-hour later with a picture of our new manatee, Tammy. "Point her out," my mother said.

The guide indicated where Tammy was floating and told us how special she was because she’d already given birth twice. Back in class, though, Randy’s picture stayed on the wall and Tammy wasn’t mentioned again. "What did we learn on our trip to Blue Springs?" our teacher asked. No one was sure.

My mother calls in the morning to tell me that the dead fish is still in the nest with the eagles. He spent all night there, head intact, body picked clean. First, water, then air, then a crooked bed of twigs. I’m going to die without any idea what I’m capable of. This is what I’d be thinking, as eagles fed me to other eagles. ●

Kevin Moffett is the author of two story collections and a collaborative novel, The Silent History. His stories and essays have appeared in McSweeney’s, Tin House, American Short Fiction, The Believer, The Best American Short Stories and elsewhere. He has received the National Magazine Award, the Nelson Algren Award, the Pushcart Prize and a literature fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts. He teaches at Claremont McKenna College and in the low-residency MFA at the University of Tampa.

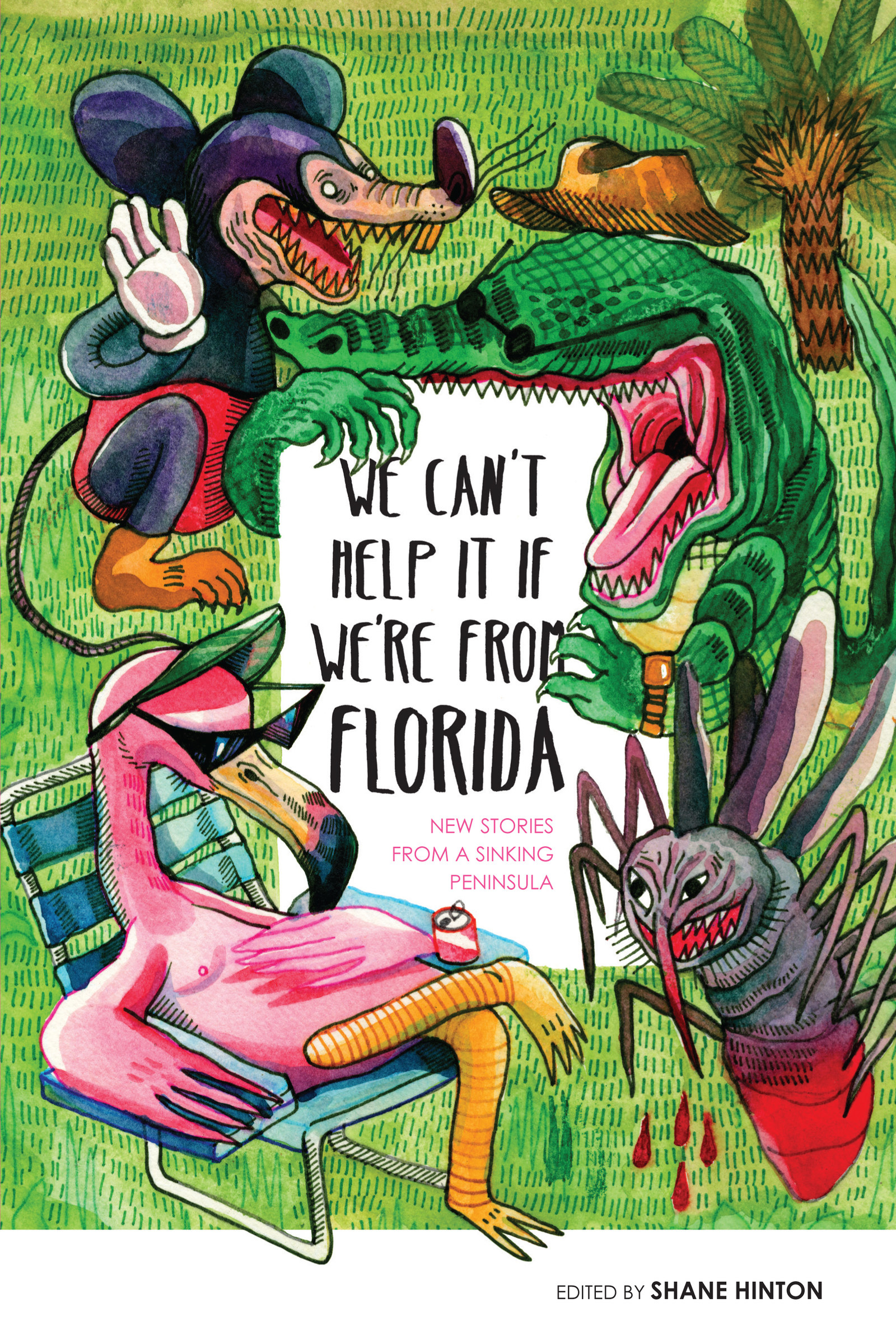

For more information on We Can't Help It If We're From Florida, click here. To read "Undoing," Alissa Nutting's story from the same collection, click here.