WASHINGTON — Cassandra Ford tends to stay online late into the evening and then sleep in. So when two FBI agents dispatched by special counsel Robert Mueller’s office pounded on her boyfriend’s door at 10 in the morning in April of this year, they woke her up.

She stumbled downstairs and opened the door, her jaw dropping when they handed her a subpoena telling her she had to testify before a Washington grand jury in two weeks. Ford didn’t recognize the first agent, who was tall, bearded, and gruff. “He was like, ‘If you don’t go, it’s not going to be good for you,’ kind of threatening,” she recalled.

But she knew the other agent, Scott Halper. Back in August 2016, he’d taken her out for coffee in her native Defiance, Ohio, to talk about the unusual way she was using Twitter. He was friendly enough at the time — he just wanted to chat about a Twitter account she’d registered that June with the username @Guccifer2.

Cassandra Ford didn't hack the DNC. But her Twitter account drew the FBI’s attention.

She’d created the account as something between a joke and an experiment — a riff off the hacktivist persona Guccifer 2.0, who at the time was slowly releasing files stolen from the Democratic National Committee. It would be months before the US government would publicly identify Guccifer 2.0 as a front for Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency, the same group that now stands accused of hacking into the DNC and taking the emails.

But during her first meeting with Halper, she never felt like she was being investigated. Halper had even told her she should consider joining the bureau.

“I do think it’s kind of funny, because if anybody’s going to walk into an international hacking incident and have no clue about it, it would be me for sure,” Ford told BuzzFeed News.

But it apparently wasn’t funny to Mueller, who is tasked with finding crimes tied to foreign influence on the 2016 election, no matter what they may be.

At the time Mueller subpoenaed Ford, he was three months away from charging 12 GRU officers, accusing them of a host of crimes related to the DNC hack and leak. Echoing something journalists and cybersecurity experts had said for a while, the indictment painstakingly detailed allegations of how the Russians used the Twitter account @Guccifer_2.

That account was an homage to Marcel Lazar, a Romanian who called himself Guccifer and hacked emails from political figures like Colin Powell and George W. Bush before being arrested in 2014 and extradited to the US, where he’s now serving a four-year sentence. But in Russia’s hands, the handle was repurposed to tweet links to stolen material, try to communicate with someone tied to Donald Trump’s campaign, and pass most of the hacked material to WikiLeaks.

Cassandra Ford didn’t hack the DNC. She doesn’t know how to hack, was never charged with a crime, and believes she’s no longer of interest to law enforcement. But her story — how a 26-year-old fell victim to Russian trolling, confused others in turn, and got swept up in Mueller’s investigation — shows how fevered some Twitter obsessives got in trying to follow the threads of Russian hacking.

It also provides a view into how Mueller's probe operates and the extent that Mueller has gone to make sure he leaves no stone unturned as he looks into Russian meddling and any connection to the Trump campaign.

Ford found herself in some weird corners of Twitter in the spring of 2016, her final semester in Penn State’s international affairs master’s program and a few months before the DNC hack. She’d been studying the situation in Syria, swaths of which at the time were controlled by ISIS, when she discovered #OpISIS, a Twitter game of cat and mouse where pro-ISIS accounts tried to connect with each other and recruit, while a network of anti-ISIS activists, identifying as Anonymous despite few displaying any hacking prowess, tracked and reported them to Twitter.

Former Twitter employees say #OpISIS wasn’t particularly effective at stopping the militants’ use of their platform. At the time, Twitter, like other social media companies, was under significant international pressure to find a way to algorithmically stop ISIS recruitment, and was tweaking what would become a relatively effective formula to block ISIS users from posting or registering new accounts.

But Ford became obsessed with #OpISIS’s immediacy, its secrecy, and the sense that people presenting themselves as both Anonymous and ISIS were interacting directly with her. She wrote a final paper for her online ethnographies course on those experiences and “the world of Anonymous that I had found myself in the middle of.”

“The writing is coherent,” her professor responded, “but at the end I’m still pretty mystified about who’s who and what’s what and the purpose of all these cloak-and-dagger communications.” He gave her a B+.

Ford headed back home to Defiance that summer, listless and spending a lot of time in her online world, more concerned with the immediacy of what her friends were saying and what ISIS fanboys were doing than with what the media reported. She didn’t care for that year’s presidential politics. She was a registered Republican from years ago, when she’d wanted to vote for Ron Paul for president, but she disliked Donald Trump and thought Hillary Clinton’s plan in Syria, to continue to aid rebels against both ISIS and Bashar al-Assad, would only continue Syria’s cycle of misery. When the DNC announced on June 14 that it had been hacked, and that the company it hired to do cybersecurity response, CrowdStrike, blamed the GRU, she missed the news.

What she did see was what her circle on Twitter was saying the next day: Some guy calling himself Guccifer 2.0 had created a WordPress blog claiming to be single-handedly behind the whole thing. Writing “DNC’s servers hacked by a lone hacker,” he posted several files as proof, including the party’s opposition file on Trump.

For many who followed the news, this was an obvious feint. It was telling that the blog had only appeared after the DNC’s announcement, and CrowdStrike was a respected company that was unlikely to stake its reputation on a such a huge claim. Because some of the released files were Word documents, and Microsoft Word captures the metadata of users who make changes, the files showed that they’d been changed most recently by someone who used Russian as their default language and had registered their name as Iron Felix, a reference to Felix Dzerzhinsky, who organized the Soviet secret police that would eventually become the KGB.

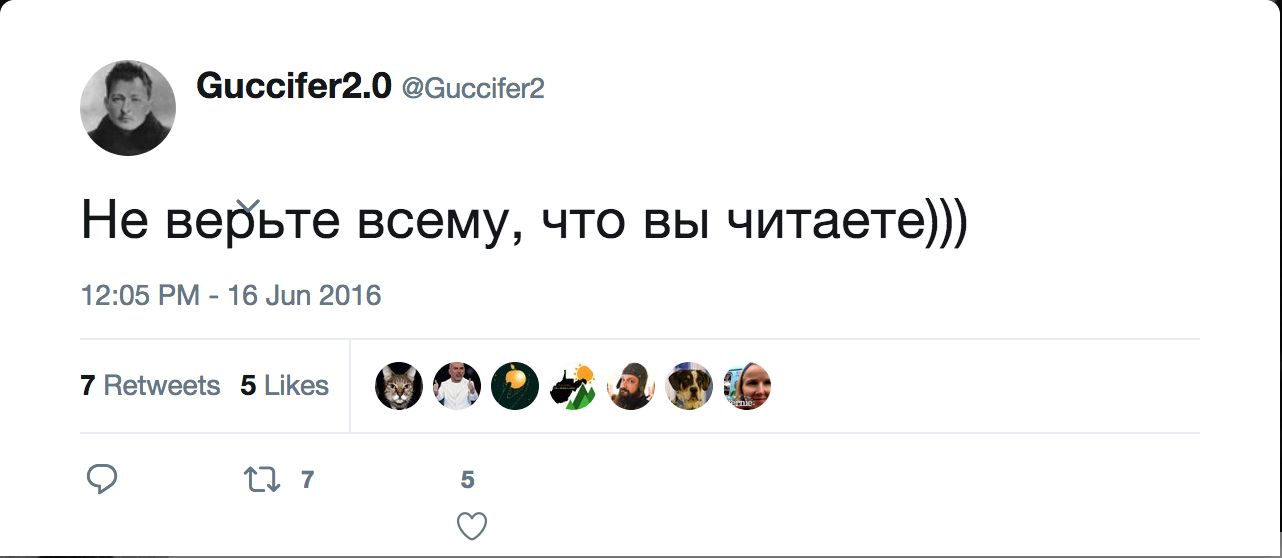

But Ford didn’t see a Russian operation — she saw a mystery. Her circle on Twitter talked excitedly about this hacktivist who had disrupted a major American political party, and she saw chatter that the term “Guccifer 2” was being censored by Twitter (Twitter declined to comment for this story). She saw one friend say it was strange that Guccifer 2 didn’t have a Twitter account, so she registered one. Skeptical of the people who claimed the metadata proved the hack was the work of Russia, and feeling cheeky about the online debate about the Russian metadata on those DNC documents, she made the account’s Twitter avatar a googled photo of Dzerzhinsky, registered its time zone as Volgograd, and, after putting a phrase through Google Translate, tweeted, “Не верьте всему, что вы читаете” (“Do not believe everything that you read”).

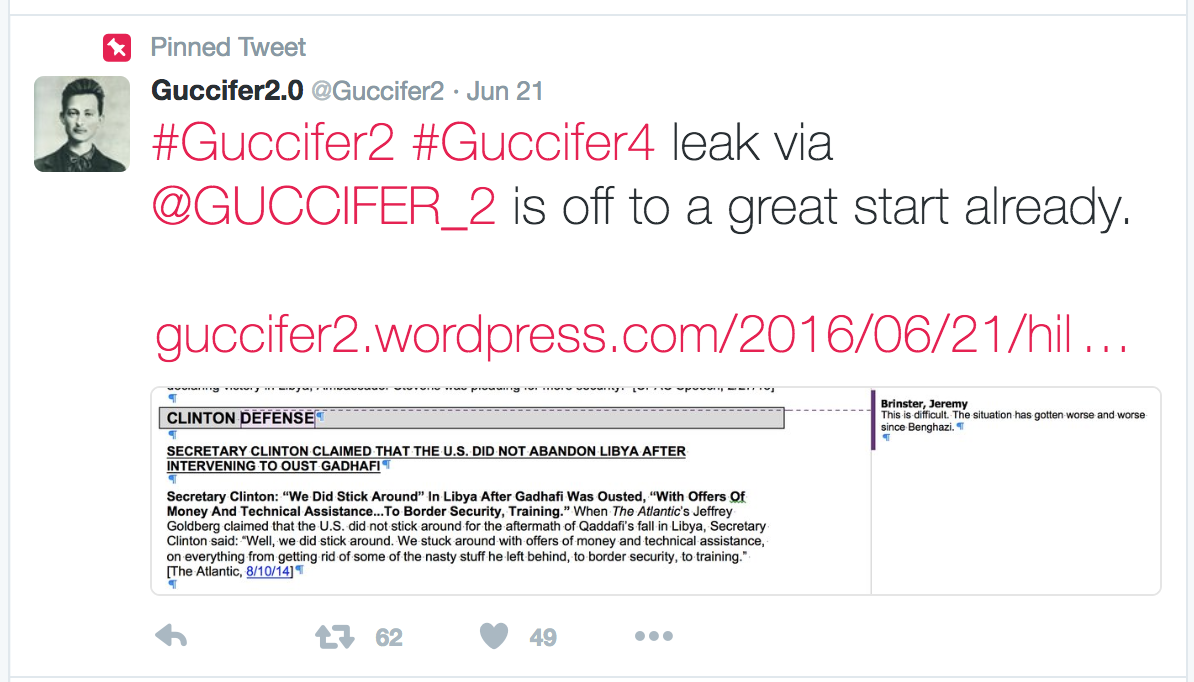

The problem with that, of course, is that Russia really was responsible for the DNC hack. In fact, according to Mueller’s eventual indictment, the Guccifer 2.0 personality and WordPress blog were hastily created on June 14 and maintained by a handful of officers in a GRU group called Unit 74455, which was located in a Moscow military building on Kirova Street nicknamed “the Tower” and managed by Col. Aleksandr Osadchuk. Those guys weren’t the DNC hackers — that was the work of other GRU officers, located in a different building — but they were tasked with disseminating Democrats’ files and emails. They finally did register a Twitter account — @Guccifer_2, because Ford had already taken the cleaner one — a few days later.

Ford doesn’t like to think of what she was doing with her account as trolling, and often when someone would ask her if she hacked the DNC, she’d tell them no, that wasn’t her. But she didn’t always go out of her way to inform people, either, and readily shared the files that the GRU released concerning Hillary Clinton.

“It was like this typical active-measures account, sowing doubt and confusion,” recalled Adam Parkhomenko, who was the DNC’s national field director in 2016. He spent months after the election obsessing over the account and sparring with Ford without ever knowing who she was.

And it was widely seen. While @Guccifer2 never reached 2,000 followers, it was retweeted and cited enough that it received hundreds of thousands of impressions in the months after its creation, according to Twitter’s analytics for the account, which Ford screengrabbed and shared with BuzzFeed News.

Technically, Twitter recognizes Ford’s account as being created June 9, and a review of her account’s archive — she shared her downloaded account history with the computer forensics firm Garrett Discovery, which gave it to BuzzFeed News with Ford’s permission — says she registered an account that day, and changed the username to @Guccifer2 on June 16, though she only recalls actually creating the account on the latter date.

For Parkhomenko, the discrepancy in dates was a smoking gun. Since it appeared the account was created before the WordPress account, he figured whoever was behind it was somehow tied to a secret Russian operation. He obsessed over how the account was registered with a Volgograd time zone and tweeted at weird hours — a result of Ford’s tendency to stay up all night online — and figured there must be some strange connection to the Russian government.

Something that @Guccifer2, the account created on June 9, the day of the Trump, Jr. and Russia meeting, and 6 days before “Guccifer 2.0” was ever public doesn’t like to be pointed out: Account was registered on 6/9, Volgograd, Russia. Tweets in Volgograd, Russia Time Zone.

@Guccifer2’s inbox — which Ford also shared, as part of her account history — soon became a honeypot for internet weirdos. One guy messaged her the email addresses and phone numbers of White House staffers, just because. One confused journalist messaged her from his verified account: “hi I am a producer at CNN. I am trying to reach Gufficer 2.0 [sic].”

Conspiracy theorists came in droves, eager to talk about George Soros, or about the Seth Rich conspiracy, which holds that murdered DNC staffer Rich was the actual source of the stolen emails — even though if Guccifer 2.0 were the real hacker who broke into the DNC, that makes the Seth Rich theory nonsensical.

Others asked her outright for hacking services, a violation of US law. “I am seeking services for file retrieval,” a Canadian man said. “I'm looking for someone to hak [sic] into a computer.” Another one asked, “Hi, can you tell me please is it possible to hack someone's twitter acct dms?”

The FBI noticed, too. Two months after she made the account, on Aug. 19, Ford received a phone call from someone in the FBI’s San Francisco field office. She was friendly, and asked about the account. Ford took control of the conversation: She had been harassed a lot online, she said, and would love to talk about it in person, and to ask the FBI if she’d been hacked.

Four days later, she met Halper and one other agent. They came from the Cleveland field office to see her at Cabin Fever, a coffee shop in downtown Defiance, a northwestern Ohio town just across the Michigan border and 160 miles from Cleveland.

Exhaustively investigating all possible angles of a hacking case is par for the course, former FBI officials say. Wannabe hackers and the real ones alike often brag, and the internet is rife with people falsely claiming credit for, or accusing someone else of, such activity. If the FBI ends up bringing charges against a suspect, their entire case file is subject to discovery from the defense. If there’s any hint that someone else might be behind a given hack, that’s a good tool for the defense, so the FBI often tries to rule out all those other possibilities to increase the chance of a guilty plea or conviction.

“I came across a lot of those types of people in my career,” said Austin Berglas, head of cyberforensics at the firm BlueVoyant and the former assistant special agent in charge of the FBI’s cyber branch in New York.

Berglas was among the FBI agents who investigated and eventually took down the Silk Road, the notorious online black marketplace, largely used to sell drugs, which at the time was the largest in history. It was the brainchild of Ross Ulbricht, who went by the pseudonym Dread Pirate Roberts. In November 2013, a month after the FBI arrested Ulbricht and shuttered the site, a replacement called Silk Road 2.0, run by a second Dread Pirate Roberts, appeared online to take its place.

“When DPR was taken down, all these fake sites and DPR2 popped up. People said this is not legitimate, that DPR is done,” Berglas said. The following year, as part of a massive law enforcement crackdown on popular drug sites, Berglas’s team arrested Blake Benthall for running the second Silk Road.

At no point in her coffee date with the two agents did Ford feel threatened. Instead, she said, she felt emboldened. They listened to her talk about the account and the abuse she’d gotten online from strangers, and told her that with her education and taste for investigative work and international affairs, she should consider the FBI or CIA, or perhaps work at a think tank. She was intrigued, but wasn’t ready to move to DC, and was spooked that her affinity for marijuana could keep her from getting a job in government intelligence. And she ruled it out completely after Trump was elected, she told BuzzFeed News, for fear of being seen as endorsing him. (The FBI declined to comment for this story, but did not dispute its broad outlines.)

Justice Department investigations are supposed to be apolitical, but that hasn’t stopped pollsters, eager to take the temperature on a case that might directly impact the president of the United States, from regularly asking Americans how they feel about Mueller. His unfavorable ratings started rising last year, according to a Marist poll, though in recent months opinion has turned and now 59% of registered voters have decided they approve of his investigation, according to numerous polls.

One of the concerns is that the investigation is taking too long without yet making a firm connection between Russian meddling and the Trump campaign. Trump himself has made that claim about Mueller, who was appointed to his job on May 17, 2017.

Congratulations America, we are now into the second year of the greatest Witch Hunt in American History...and there is still No Collusion and No Obstruction. The only Collusion was that done by Democrats who were unable to win an Election despite the spending of far more money!

But the scope and importance of the investigation are precisely why it’s dragged on for a year and a half with no end in sight, said Alan Rozenshtein, a law professor at the University of Minnesota and a former cybersecurity and foreign intelligence adviser to the Justice Department.

“This is simply them being very thorough. These are Boy Scouts. In the same way that the Secret Service tracks down every threat against the president, no matter how silly it may be, I suspect they are tracking every shred of evidence related to possible Russian hacking,” Rozenshtein said.

“I think there’s an intuition that the more important the investigation, the faster it should go. And I think that’s understandable, but in fact it’s the other way around. I can’t think of a criminal investigation whose stakes are higher, ever, in the history of the republic, in a certain sense. So you really want to get it right.”

Ford’s April 2018 subpoena asked for more information than she could provide: all documents she could access concerning not only the @Guccifer2 account, but also @Guccifer_2, the WordPress account, and, for good measure, WikiLeaks and DCLeaks, another site that the GRU registered to leak hacked US political material.

After the two agents left her doorstep, Ford talked to her boyfriend, who recommended she talk to Cathy Elliott Jones, a lawyer based in Ventura County, California, who considers herself an “earth mother” adviser to Anonymous, and who has a habit of pausing, mid–phone call, to yell “fuck you, FBI!” in case her phone is tapped. Jones called a lawyer friend, who in turn recommended Jim Klimaski, a 72-year-old DC attorney who specializes in military and employment law, but who was both experienced and willing to take her on for free.

“Some lawyer in San Francisco called me up, wherever she was, Sacramento or something, and begged me to take this on, and I said OK, she can come over here and I’ll walk her to the grand jury office,” Klimaski told BuzzFeed News.

Ford brought printouts, including her Twitter confirmation email and account details, and headed to Klimaski’s office the morning of April 20. They shared a cab over to the Department of Justice, and were seated in a small, windowless conference room across from assistant special counsel Kyle Freeny and senior assistant special counsel Jeannie Rhee. Alex Kobzanets, an FBI special agent who has investigated Russian cybercrime cases, sat at the head of the table and didn’t speak much.

Ford wouldn’t be forced to testify, Freeny said, but after the meeting, she would have to hand over more files from her Twitter account, as well as some Telegram chats, and answer all their questions. (Freeny directed BuzzFeed News’ inquiries for this story to the special counsel’s spokesperson, who confirmed the job titles of the people in this story but otherwise declined to comment.)

Freeny was friendly, a good cop to Rhee’s accusatory bad cop, Ford said. They talked about the account, how Ford had thought to register it, and about Jonathan Langdale, an estranged Twitter friend who had privately messaged her advice on how to handle @Guccifer2 in its early days, according to Twitter direct messages Ford provided to BuzzFeed News. When emailed for comment, Langdale replied that “In my view, your outlet publishes CNN-type propaganda, like the so-called-‘dossier,’ without verification,” and declined to answer questions.

The prosecutors had printed out some of @Guccifer2’s tweets on high-quality, glossy paper, which Ford found funny, and they asked what she had been thinking when composing them. One printed tweet was one of that account’s first — a retweet of someone else talking about ActBlue, a Democratic fundraising platform. In Ford’s mind, the tweet was interesting because it pertained to a class-action suit, since dismissed, that accused the DNC of unfairly helping Hillary Clinton beat Bernie Sanders in the primary. But for the special counsel, ActBlue was a red flag: GRU officers had hacked the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee to change a link to ActBlue to one for Act Blues, a phishing page GRU hackers had set up.

Kobzanets, the FBI agent who specializes in tracking Russian hackers, was more interested in who Ford knew, asking for details about international Anonymous affiliates she had communicated with, but it seemed to Ford that she wasn’t helpful.

“They seemed to already know everything before they started,” Klimaski recalled.

As the conversation dragged on, Kobzanets appeared to grasp at straws for potential leads, Ford said. “He was like, do you have any Russian friends? Do you know any Russians? I really sat there and thought about it, and was like, I don’t think I do.” (Kobzanets didn’t respond to attempts to verify those comments.)

Twice, the special counsel employees excused themselves, left together, and returned. When they were finished with their questions, they told Ford she wasn’t a target, but asked her to hand over her phone and laptop. She hesitated, but Klimaski and Jones, reached by phone, both told her that while it was debatable whether the subpoena covered her devices, it wouldn’t be any trouble at all for Freeny to write a new one. She acquiesced, and got the devices back a few days later.

That was the only time Klimaski and Ford met in person. He went on with his practice with other pro bono work. Two months later, Mueller filed his indictment against the GRU officers, including those accused of running @Guccifer_2 and those who allegedly hacked the material that account disseminated.

“We never heard from them again,” Klimaski said.