At first glance, you couldn’t see much of a difference between DEF CON, the notoriously rowdy American hacker conference, and its newly formed franchise in Beijing, where in May China hosted its first hacker conference.

Famous American speakers still gave technical talks while bathed in neon green light. Upstairs, instructors in small rooms offered hands-on classes on soldering computer chips, social engineering (the art of convincing someone to do what you want, like clicking a phishing email), and picking locks. Just outside, two dudes in jeans and T-shirts plugged a laptop into a sedan and invited you to try your hand at hacking its console.

What you wouldn’t notice was the Chinese government’s presence lurking just beneath the surface. While the lock-picking village let you try your hand at various padlocks, government officials had objected to instructors bringing in handcuffs; they didn’t want imagery of people breaking free from custody. The two men running the car-hacking village were in China before they learned they would, indeed, be provided a rental car to mess with. Though they could tell it was a Chevy Cruze, and assume its age, they couldn’t tell for sure, because all identifying marks had been covered with heavy black tape to obscure the model.

In the mornings, before any talks started, Valerie Thomas, who volunteered to run a workshop on how to bypass building security and stayed at the conference’s hotel, woke up to see several dozen men in black suits receiving security instructions; they were assigned to stand in the hallways and at entry and exit points all day.

“I was surprised at the number of agents they had,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I guess when you’re in a controlled state that’s just what you do.”

Even the conference's logo had gone through government approval. Jeff Moss, DEF CON’s founder and owner, originally submitted an outline of the US and China on a motherboard. But three different government officials had objected, insisting that China’s outline must include Taiwan.

“I’m like, well, I also didn’t include Alaska and Hawaii. I didn’t include Hong Kong,” Moss said. He settled with a version of the map that included the entire world.

Moss had a litany of reasons for choosing to bring his show to China: the challenge; the guarantee that, in a country with so many people and so much high tech, he’d get good attendance; a good friend at Baidu, the Chinese search engine whose team of dedicated government liaisons was necessary; a longstanding push for his whole family to learn Mandarin, his wife’s native language. Chinese tech companies kept sending more and more teams to competitions at DEF CON and other Western conferences, and became serious international competitors.

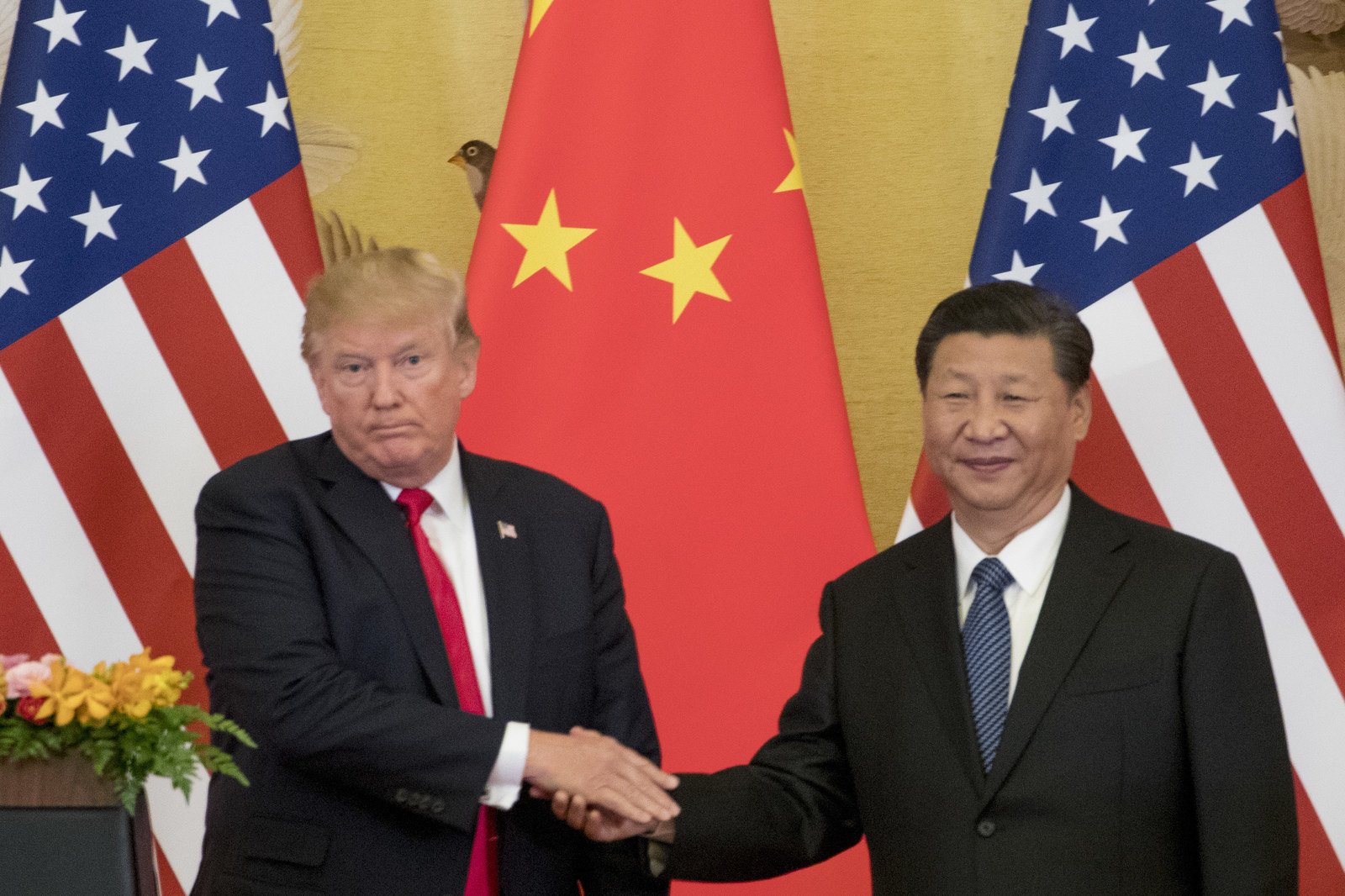

“Going forward, really, the superpowers in cyberspace are America and China,” Moss told BuzzFeed News. “From the number of products they produce, market forces, patents, innovations, money spent on R&D, whatever it is, it’s going to be our two countries.”

But while Moss and others with DEF CON are reaching out to China’s cybersecurity community, China’s government is forcing its cybersecurity researchers to retreat from the outside world.

An opening salvo was in 2016, when the government suddenly closed its best-known platform for reporting software vulnerabilities, Wooyun, and arrested its founder, a former Baidu employee. The next year, Zhou Hongyi, the billionaire founder of Qihoo 360, China’s largest antivirus company, announced that unreported software vulnerabilities “should remain in China.” Police in China recently said they intend to enforce laws that would prohibit unauthorized disclosure of detected vulnerabilities, and in March, Chinese hackers abruptly pulled out of a Canadian competition they had begun to dominate.

It’s not just hackers who are forced by the Chinese government to look inward. The country’s tech industry is consolidated around a handful of tech giants, all increasingly under the thumb of President Xi Jinping, who in February abolished term limits. Those companies are key to his “Made in China 2025” plan, which envisions China as both a leader in industries like robotics, artificial intelligence, and green energy, and a hub of high-tech manufacturing.

“The Chinese government wants an equally capable and more compliant InfoSec community that it can direct to favor Chinese national security over all else,” said Priscilla Moriuchi, the former head of the National Security Agency’s East Asia and Pacific cyber threats office during the Obama administration.

Ma Jie, the head of cloud security at Baidu, said that cybersecurity employees who work at different Chinese tech companies are less likely to see each other as rivals.

“China’s more like a community. Probably sometimes we fight or disagree with each other, but those of us on the technical side, we’re friends,” Ma told BuzzFeed News on condition his company could approve quotes before they were used in a story. He pointed to how his colleagues at China’s other major tech companies socialize with each other at foreign conferences, even holding dinners and mock awards ceremonies together.

“We should know each other; we can avoid a lot of misunderstanding,” he said.

Closing ceremonies in the books - a very successful #defconchina beta complete! Thank you to the attendees for the warm welcome, to @Baidu_Inc and #xfuturesecurity for all the hard work and to the #defcon staff for making it happen! Looking forward to more! https://t.co/aSYkSvAPtb

As the United States has seen firsthand, a decision to hoard a giant vulnerability, rather than contacting engineers to fix it, can produce disastrous consequences. The most destructive cyberattack in history came after a strange “hacker” group going by the name “Shadow Brokers” — their identity is still unknown — appeared in 2016 to leak an elite, NSA-developed tool to exploit Windows, called EternalBlue.

But even though the NSA gave Microsoft enough notice about EternalBlue for it to issue a new patch a month before the Shadow Brokers leaks, plenty of people either didn’t update their operating systems quickly or were using pirated versions of Windows that couldn’t be updated. Russian military intelligence, which tends to harass Ukraine, used EnternalBlue to build a crude ransomware worm called “NotPetya,” designed to lock up Ukrainian government computers the day before a national holiday. It worked too well, spreading to computers around the world, causing more than a billion dollars in damage and leading to further US sanctions on Russia.

Still, Microsoft President Brad Smith largely blamed the NSA for the damage EternalBlue did to the world. “Repeatedly, exploits in the hands of governments have leaked into the public domain and caused widespread damage. An equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be the U.S. military having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen,” he wrote.

But the US has been reckoning with vulnerability disclosure since at least 2008, and in 2014 instructed the NSA to largely stop hoarding vulnerabilities. As of last year, the agency said that its researchers alert a company that their product has a vulnerability, rather than keeping it for the NSA to exploit, about 90% of the time.

China, on the other hand, is moving toward hoarding those exploits. And that’s part of why it’s forcing its cybersecurity researchers to stop sharing with the rest of the world.

“They see US companies as working with the US government, like Chinese companies are forced to, to the detriment of Chinese information security,” Moriuchi, the former NSA East Asia chief, told BuzzFeed News.

China, like the US and a number of other countries, does maintain a public database of software vulnerabilities that’s a vital resource for IT professionals everywhere. But China also often quietly falsifies the date when a vulnerability was discovered, which lets China’s elite government hackers continue to exploit a vulnerability until it is no longer useful. Moriuchi’s company, Recorded Future, recently released a study that showed that the Chinese government quietly and consistently obscures the real dates on which vulnerabilities were disclosed. That lets Chinese hackers hide when they were using an exploit.

The result of a country with China’s research resources keeping vulnerabilities to itself increases the odds the world will see another NotPetya-level disaster, said Jason Healey, a senior researcher at Columbia University who focuses on vulnerability research.

“Spies and cyberwarriors in China and the United States will discover different vulnerabilities,” Healey told BuzzFeed News. “This effect is magnified because the US is most likely to disclose new vulnerabilities that would have the most impact. Because they don’t disclose, China is likely to have more of these globally impactful vulnerabilities in their arsenal.”

As DEF CON ended, President Trump began dodging and weaving, in public comments and on Twitter, about whether he was conducting a trade war with China. Trump insists on reducing the US trade deficit with China, but he's also vowed to help China save phone giant ZTE, which has been crippled by US sanctions after it was caught sending its products to Iran and North Korea. ZTE's developing technology, like 5G, are a key component of China's 2025 goals.

The US knows 2025's importance to China. A number of the items it’s threatened with major tariffs are high-tech, like satellite parts and industrial robots. Next week, it will begin a new program of further limiting how long Chinese students who study high-tech industries can stay in the United States.

Whether this spat leads to the two countries moving away or to a temporary truce is yet to be seen. Most recently, Trump signaled on Twitter that convincing China to buy more American soybeans was a top priority, and Trump recently said he was working to give ZTE “a way to get back into business” after his daughter Ivanka won a series of trademarks in China.

Conferences like DEF CON provide some long-term benefit to friendships between cybersecurity experts in the two countries, said Jake Braun, the former White House liaison to the Department of Homeland Security, who attended.

“Down the road, from a national security and foreign policy perspective, the average age here is probably 28, 30,” he said of the DEF CON attendees. “These are the people who in 10 years, 20 years, will be running the intelligence agencies, the cyber divisions of the military, and the Homeland Security equivalent. For us to get to know these folks now, in this setting, without all the pomp and circumstance, to have a beer with them after the conference, is going to be very good for us in the long term.”

But for Moss and the other DEF CON hackers who traveled to China, their role is to make the internet and computing safer, not to push US interests in a conflict with a would-be fellow superpower.

“Internet problems are global problems, which means we’re going to be dealing with security folks in China no matter what,” Moss said. “So let’s have some relationships, let’s build some friendships, and then if things do go wrong or if you do need to talk to somebody, you’ve got some connections.”

Besides, even if Moss didn’t bring his conference to Beijing, someone else with just a little less brand recognition would fill that role. DEF CON just barely made it in time. Hack in the Box, a hacker conference currently held in Amsterdam and Malaysia, comes to Beijing in November.

“Everybody else’s going to get in there and compete,” Moss said. “It’s not that people were only talking to us, trying to get us to come into China. Lots of people were talking to lots of different conferences.”