When Donald Trump was talking about a return to the past as he announced his bid for the White House in 2015, parallel to his rhetoric, photographer Leah Frances decided to go on a journey into America’s obsession with nostalgia and what that concept meant to her.

Growing up in Canada, Frances found American diners to be charming artifacts that she remembered seeing in movies and TV shows. The establishments often sport neon signs, bright color palettes, and period furniture.

For Frances, seeking out these eateries became a peaceful oasis during turbulent times after the 2016 presidential election. The project lasted for years and the nostalgia of ’50s-themed diners had a different effect during pandemic lockdowns and racial justice protests of 2020.

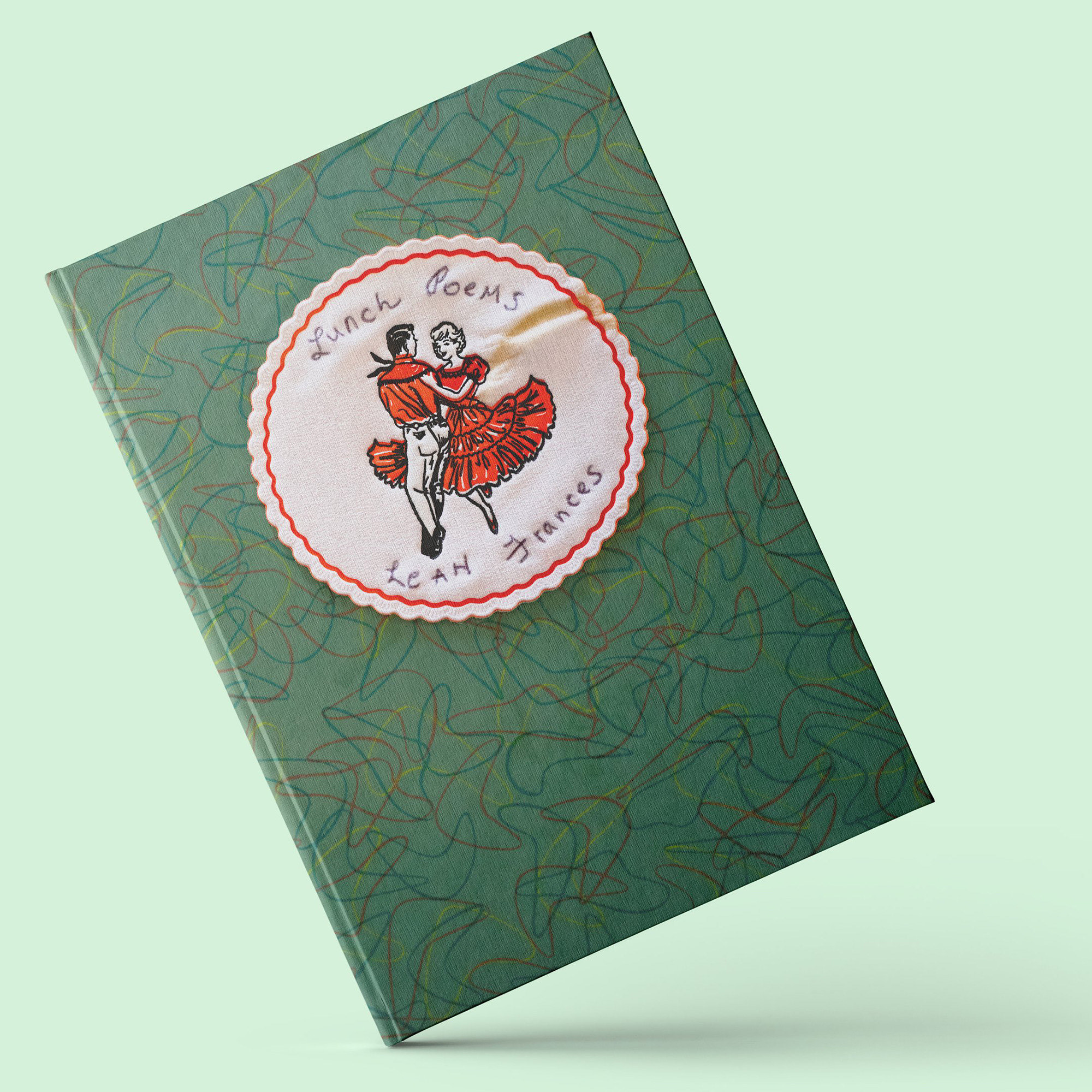

Using the motif of “third places” as her vehicle, Frances was able to pull her thoughts together in a new book titled Lunch Poems. “Third places” (or “third spaces”) is a term coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg referring to shared environments that are outside of home (a “first place”) and work (a “second place”). They can include bars, restaurants, parks, and movie theaters. They can be physical areas where people share a sense of community and exchange ideas, learn, eat, drink, or merely have a good time.

What inspired this series of images?

I would say that I’ve always been interested in the ideas of nostalgia that I saw around me in America. Coming from Canada, I wasn’t as aware of that. I don’t think we have a period of time in Canada where we were “the best” or that kind of thing, so we don’t have something that we look back on with desire. So in the beginning, I was investigating areas such as diners that I think have become almost mythologized in films and television. I was really interested in the idea that we haven’t seen them firsthand; we see them in television shows that are re-creating them 20 or 30 years later. So I was really interested in going to those spaces and photographing them as they are now.

How does that idea relate to modern day?

As I started editing the work, my prism that I was looking at it through was obviously everything that’s going on now, so a lot of those photographs were made during the pandemic as well as Trump’s [presidency] and the climate crisis, the Black Lives Matter movement. Just so much was happening. When I looked at the photos I had been taking, especially during the pandemic, they’re all empty. There were no people there, and I began to build on that. It looked almost postapocalyptic. So I began to think about these mythologized American spaces and photographed them empty to symbolize the divide in this country. I [initially] set out to investigate ideas of America, and in the end I sort of started photographing particular scenes to express where we are now.

What inspired the title of Lunch Poems?

Lunch Poems is the title of a book of poetry by Frank O’Hara and what I started to think about, which is highly personal to me, is that he made his poetry on his lunch breaks when working at the MoMA. He worked at the front desk there, and then he moved on to be a curator. I work at the Allentown Art Museum at the front desk, and I started really thinking about art, labor, and money. I’m a working-class artist, and art is something I’ve done on my metaphoric lunch break from what I’m being paid to do. It’s never been something that people consider as my real job, because labor is generally validated by getting paid. It’s kind of like a chip on my shoulder. I think about my struggle with what the labor of art is worth and how it’s generally unpaid, so it’s often seen as a hobby or not the same as what you go do in an office. I think particularly as a woman, I started to worry about the worth of my labor …if it wasn’t contributing to my marriage and household, because I’m used to being really independent. So that’s where the title came into play for me, personally.

How long did it take to photograph this series of images?

The entire series was shot during the Trump presidency and shortly thereafter, so probably about five years. I just really began to think initially about the idea of nostalgia as something that a lot of people seem to want to get back to. The idea of “making America great again” and getting back to a certain place really came to the forefront during this period of time I was photographing. Initially, I was interested in nostalgia because I didn’t know a lot about it and it seemed to be coming to a head in America as a force. So the work does encompass that time period where that idea bubbled to the surface, if you will, from 2015 to 2021.

Throughout the project, where did you go?

I moved while making that work from Brooklyn to Easton, Pennsylvania, so for the most part I’m interested in photographing areas that I know well and that are local to me, so there are pictures from New York, and there are pictures anywhere I can drive from my home within an hour or hour and a half. But then occasionally when I was traveling already to see a close friend, I’d also make a photograph. There are also a couple of images from LA and a couple from Atlanta. But I'm really trying to make it a part of my practice to know well the places that I'm making work about because I think it’s really important to represent a place that you know. Since I'm making a frame around the image with my camera and telling people this is something to look at, I think it’s different if you're not super familiar with a place versus when you are.

What do you hope people take away from this series?

I think the photographs are pretty open-ended, and I like that. I did just do an MFA, and I was frankly pretty battered about that my work wasn’t super well accepted at school, so I’m really weary of work that you have to know what the artist intended or it makes no sense. Or work that you have to have read a lot of critical theory to understand.

I do love the fact that for one, people from the towns that I photographed seemed to have enjoyed the work. They write to me on Instagram or had come out to my recent show. So in that case, maybe they’re just taking away [that it’s a beautiful photograph] or That’s somewhere where my grandfather goes after his doctor’s appointment. I’ve heard that, That’s somewhere that’s familiar to me. Whatever people get out of a photograph is fine. I have heard that the idea of a sort of sadness and division is coming through without even reading my artist’s statement.

I would love it if we could all try to think of a way to get along. I don’t know how that works. It seems like the system is broken right now. When I was making that work, I was trying to look incredibly closely at this American myth and to think deeply about it. I feel like if we all look more closely, is there any common ground that we can find? I don’t know, and it’s super difficult, and there’s some topics where I don't think there is common ground, nor should there be — but what are we going to do? How are we going to move forward as a country? I don’t know, so I was trying to explore that with these pictures, and I hope people get to thinking a little more.

What did you learn from shooting this series?

When I was making the work, I began to become really frightened at times because of some of the signage around certain political ideologies and such. Things that I’d run into in some towns, I felt deeply upset or frustrated or angry or scared, anxious, confused … all these things when I would come across these violent slogans. My husband often drives me, and he stopped wanting to go out in the world and drive me places because he’d also get so upset.

So part of it was trying not to instantly judge a place or a person by what they look like or what I'm expecting. Not to expect something negative all the time. It’s difficult. I was really worried about what’s happened to me during the Trump era, how I will occasionally see someone and judge them, that they may have certain political beliefs and I don't think that’s doing anyone any favors. So going to all these small towns and going to so many places in Pennsylvania, which is an important swing state. And you may go one place where Donald Trump had been the day before. I found it frightening. I try to have a more open mind and not judge somebody before you talk to them. That was the most basic thing [I learned].

How did working as a server on and off inform your perspective?

I photographed what are known as “third spaces,” spaces we gather outside of the home and work, which were mainly diners and restaurants. I was a waitress off and on for 17 years, so something I was thinking about is how I'm highly aware of having an income that is dependent on tips, and that’s really changeable day to day, and how precarious that can be and how many of us out here are living that way.

So I was thinking about that during the pandemic because I have lived that way myself. I was thinking about the actual spaces themselves and who works there, or who had worked there, because so many of these places have closed since I had photographed them. The restaurant world is personal to me as a place where the bulk of the labor we see is done by women. Of course there are both men and women in the kitchen, but most often who greets you, especially in a diner, is going to be a woman.

How does color play a role in your work?

I love color so much, and I think it is a strong component. [For previous day jobs,] I spent years looking at color in photography for how it prints in a magazine, and so I think I am really drawn to that when I'm out making work. But also, as I was saying, I was kind of really struggling with that kind of frustration of that us-versus-them mentality that seems to be going on and all of the fear and anger and anxiety that I was feeling. I tend to shoot in the golden hour, so I harnessed that light to sort of grasp at some element of joy in what are pretty complicated environments at times. I was talking to a curator and I said something like that, and he said, “Oh, so you made light your friend?” I guess that’s true, a certain color of light, the warm light at golden hour, is soothing and makes me happy. So if I was out there and slightly frightened or upset or confused, it would be something that’s very personal to me, and that would make an experience for me that would hopefully come across in the work.