Dollhouses have been popular for centuries — for good reason. It’s fascinating to see our lives in miniature, and they give children the opportunity to practice social skills and rehearse for real-life situations. Peer closely at the exquisitely detailed “nutshells” by mid-20th-century miniaturist Frances Glessner Lee and you’ll see the typical dollhouse domestic scenes: tiny furniture, household items, decor, and, of course, dolls.

But Lee’s dolls are dead. Horrifically so: Soaked in blood from gunshot wounds. Hanging from the rafters, a noose around their neck. Sprawled on a hardwood floor, their head bashed in and a (minuscule) hammer nearby. There’s even a baby in a crib, blood splattering the headboard and wall behind it.

These gruesome crime scenes aren’t meant for morbid entertainment. Instead, Lee, the nation’s first woman police captain and a forensic science pioneer, created these dioramas — called the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death — as a training tool for homicide investigators to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.”

Born in 1878, Lee didn’t begin constructing the Nutshells until the 1940s, when she was a grandmother and heir to her family’s fortune. As a younger woman, she’d wanted to attend Harvard Medical School but was denied admission because of her gender. Decades later, she helped establish Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine, the first university program to train crime scene investigators using scientific techniques. The curriculum included studying the intricate details of her crime scene dioramas, reading “case files” (the nutshells are based on real investigations), and looking for clues to deduce whether the doll-sized death was a result of murder, accident, or suicide.

The dioramas were part of a Smithsonian American Art Museum exhibit five years ago, but now they are being held at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore. There, they are still being used specifically for forensics training classes — so which Nutshells actually show a crime remains known only to instructors.

Before you book that ticket to Baltimore, I have some bad news for you: The Nutshells aren’t open for public viewing. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to look for clues in these photographs and formulate a theory yourself!

Three-Room Dwelling

On Monday, Nov. 1, 1937, shoe factory supervisor Bob Judson, his wife, Kate Judson, and their baby daughter were discovered dead by a neighbor, Sarah Abbott, after Bob failed to meet her husband to drive to work together as planned.

Not seeing Bob or any signs of activity at the Judson house after Paul left, Sarah went over to their porch at 8:15 a.m. and tried the front door, but it was locked. She knocked and called but got no answer. The kitchen door was also locked, but through the window she said she could see a gun and blood, so she ran home and notified the police. The model shows the premises just before Sarah went to the house.

Clues: The table was neatly set for breakfast, presumably the night before, and there is a rifle on the kitchen floor, next to the baby’s high chair. There is a flashlight beside the telephone on Kate’s nightstand. Both exterior doors were locked from the inside, and no lights were on in the house. (Sunrise was at 6:17 a.m. that day) Chairs are toppled in both the nursery and bedroom; toys are knocked over, and a teddy bear is on the floor. There is a pool of blood in the nursery and what looks like bloody footprints or drag marks leading from the bedroom entryway to Bob’s body. Could that be blood splatter on and around Kate’s head?

Notes: Lee hand-knit the tiny white teddy bear beside the toppled chair in the nursery. While she paid a carpenter to build the furniture and cabinetry in all the dioramas, Lee herself created everything else. Here, she used red nail polish for the blood seen throughout the house.

Barn

On Saturday, July 15, 1939, Eben Wallace, a local farmer, was found dead by his wife, Imelda. After disagreements, she told police, her husband habitually went to the barn, stood on a bucket, put a noose around his neck, and threatened suicide. She always talked him down. On Saturday around 4 p.m., they had a dispute but she didn’t follow him to the barn right away. When she did, she found him dead, standing on a collapsed crate. The sturdier bucket wasn’t in the barn; she said she’d used it and left it outside by the pump. The rope was always kept fastened to the beam just the way it was found — it was part of the regular barn hoist. Is it murder if Imelda Wallace, tired of her deeply unpleasant husband’s manipulation, hid the bucket, and maybe even put a flimsy crate in its place?

Burned Cabin

On Saturday evening, Aug. 14, 1943, Phillip Perkins said he had come to spend the night with his uncle, as he frequently did. In the middle of the night he was awakened by the smell of smoke and ran outside to find the house on fire and fire engines arriving. He said he had been very confused and could not remember any other details. Firefighters arrived at 1:30 a.m. and quickly extinguished the fire before the building was completely destroyed. One of them noticed Perkins, fully clothed, wandering around near the house, but his uncle was missing. The model represents the premises after the fire was extinguished and before the investigation was started or any part of the premises disturbed.

Clues: Based on the state of the bed compared to the rest of the house, it would seem the fire originated there. There is no immediate evidence of the uncle’s body — but in a similar, contemporaneous crime, a killer had rigged an alarm clock to explode while their alibi had them elsewhere. Lee biographer Bruce Goldfarb noted that there is an alarm clock in this diorama, possibly a cheeky nod to the sensational real-life murder. In that case, the remains were found in the cellar after the fire caused the floor to collapse.

Note: Lee constructed the cabin in full, completely undamaged. Then she used a blowtorch in an apparent effort to replicate the famous arson.

Dark Bathroom

On a Sunday night in early November 1896, Maggie Wilson was found dead in her bathtub by Lizzie Miller, a neighbor in their rooming house. Miller, who only knew Wilson in passing, told police she thought Wilson was subject to seizures. She said a couple of male friends regularly visited Wilson, including that Sunday night, when she believed they were all drinking. Sometime after they left, Miller heard the water still running in the bathroom. Upon opening the door she found the scene as set forth in the model.

Clues: It’s hard to confirm with a doll, but the body seems to be in rigor mortis, there appears to be lividity in the face, and her clothes and the bathtub are dry. If she’d been preparing to take a bath, it would seem that she would at least have put the stopper in first, and it’s clearly hanging off the side of the tub. It’s entirely possible that Wilson had a seizure and drowned, but the timing and circumstances could call into question whether she was alone when she died.

Kitchen

On Tuesday, April 11, 1944, Fred Barnes called police to say that his wife, Barbara, was lying unresponsive on their kitchen floor. He said that he had left the house at 4 p.m. to go downtown on an errand for his wife and returned about an hour and a half later. Although the outside kitchen door was standing open when he left, it was now locked. He attempted knocking and calling but got no answer. He tried the front door but it was also locked. He then looked in the kitchen window, which was closed and locked, and saw what appeared to be his wife lying on the floor. He then summoned the police. The model shows the premises just before the police forced open the kitchen door.

Clues: The gas stove jets are on and Barbara’s face has the rosy complexion typical of carbon monoxide poisoning (Lee painted all her dolls’ faces to indicate lividity, or lack thereof), and newspaper has been stuffed at the bottom of the doors. But did she really decide to kill herself in the middle of cooking and baking and washing and taking ice cubes out of the refrigerator? Is it significant that the iron is precariously placed — in an otherwise extremely tidy kitchen — on the edge of the ironing board near where she fell? Note that we (aka the crime scene investigators here) can’t see the back of her head.

Living Room

On Friday, May 22, 1941, Reginald Davis said he discovered his wife dead on the stairs. The previous evening his wife had gone upstairs to bed shortly before he had. On Friday, he awoke a little before 5 a.m. to find that his wife was not beside him in bed. After waiting a while, he got up to see where she was and found her body. He at once called the family physician who, upon his arrival, immediately notified the police.

Clues: Is it significant that there are so many cigarettes and stubs on the side table? Or that all those newspapers are scattered on the floor, in what is otherwise a very tidy house?

Notes: Lee hand-rolled the cigarettes herself using real tobacco, and she also made the covers of the magazine and newspapers, which are readable despite their minuscule size.

Log Cabin

On Thursday, Oct. 22, 1942, Arthur Roberts, a married local insurance agent, was found dead at a log cabin by police who responded to a call from his girlfriend, Marian Chase. She told police they frequently met at the cabin, most recently the previous evening. Chase was also married but separated from her husband. She said Roberts had broken up with her, but they did not argue. While both were standing at the foot of the bunk bed, he turned toward the door, took out a cigarette, and dropped it. As he stooped over to pick it up, she heard a shot and he fell flat, with a gun dropped beside him. She picked up the gun, which she said did not belong to her, put it down, and then ran out the door, jumped into her car, and drove to summon the police.

The gun was identified as belonging to Roberts, and Chase said the handbag on the bed was hers. A single bullet had passed entirely through Roberts’s chest from front to back, and the powder around the entrance hole indicated it had been fired at a fairly close range.

The model shows the premises just after Chase left and before her return with the police officer.

Parsonage Parlor

On Friday, Aug. 23, 1946, high school student Dorothy Dennison was found dead after being reported missing by her mother. The mother told police Lt. Robert Peale that on Monday, Aug. 19, Dorothy had walked downtown at around 11 a.m. to buy some steak for dinner. She didn't have much money in her purse. When she failed to return in time for dinner, her mother telephoned a neighbor, who said she had seen Dorothy walking toward the market but had not seen her since. The proprietor of the market confirmed to Mrs. Dennison that he had sold Dorothy a pound of steak sometime before noon but didn't notice which way she turned upon leaving the shop. At 5:25 p.m., Dorothy’s mother notified police, who began inquiries and, on Wednesday, made a systematic search of all closed or unoccupied buildings in the vicinity. Four days after she went missing, Peale and another officer found Dorothy’s body at a parsonage; the premises are as represented in the model.

Clues: The temperature during that week had ranged between 86 and 92 degrees with high humidity.

Dorothy’s body shows that she hasn’t been dead for long, but the meat on the chair is covered in flies. The parsonage clearly hasn’t been occupied: The chairs are covered and the lamps covered and tied up. There is no indication on the body that she had been tied up. There is significant trauma to her head; it is surrounded by blood, and a bloody hammer is on the floor nearby. A knife is sticking out of her chest but there is no indication of blood from that wound. The top of her dress has been pushed down, exposing her naked chest, and her skirt is pushed up.

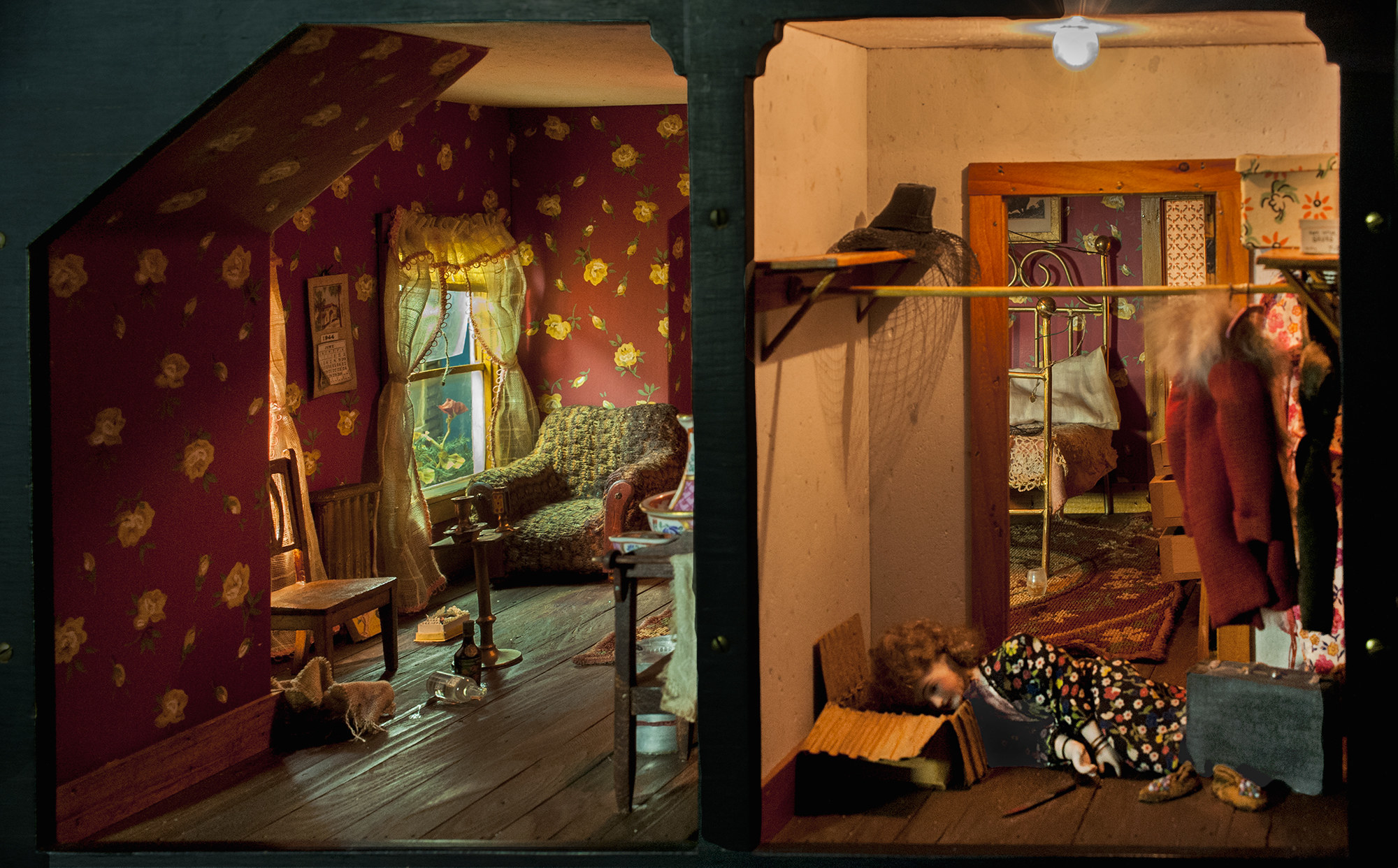

Red Bedroom

On the morning of Thursday, June 29, 1944, Marie Jones, a sex worker, was discovered dead by her landlord, Shirley Flanagan, who noticed her open door. She said Jim Green, Jones’s boyfriend and client, had come in with her the afternoon before, but she didn’t know when he left.

Green told police that on the afternoon of June 28 he had met Jones on the sidewalk and walked with her to a nearby store, where he bought two bottles of whiskey. They went to her room, where they sat smoking and drinking for some time. Jones, sitting in the big chair, got very drunk. Suddenly, without any warning, she grabbed his open jackknife, which he had used to cut the string around the package containing the bottles. She ran into the closet and shut the door. When he opened the door, he found her lying as represented by the model. He left the house immediately after that.

Clues: If Jones slashed her neck in the closet, why are there what appear to be bloodstains on the floorboard in front of the chair where she was sitting and the rug beside it? Shouldn’t there be more blood surrounding her neck wound? Why are all of the drawers flung open on the dresser outside the closet door?

Correction: If you look closely, you can see a rifle on the floor by the baby’s high chair in "Three Dwelling." A previous version of this story said that the weapon was not visible in this photo.