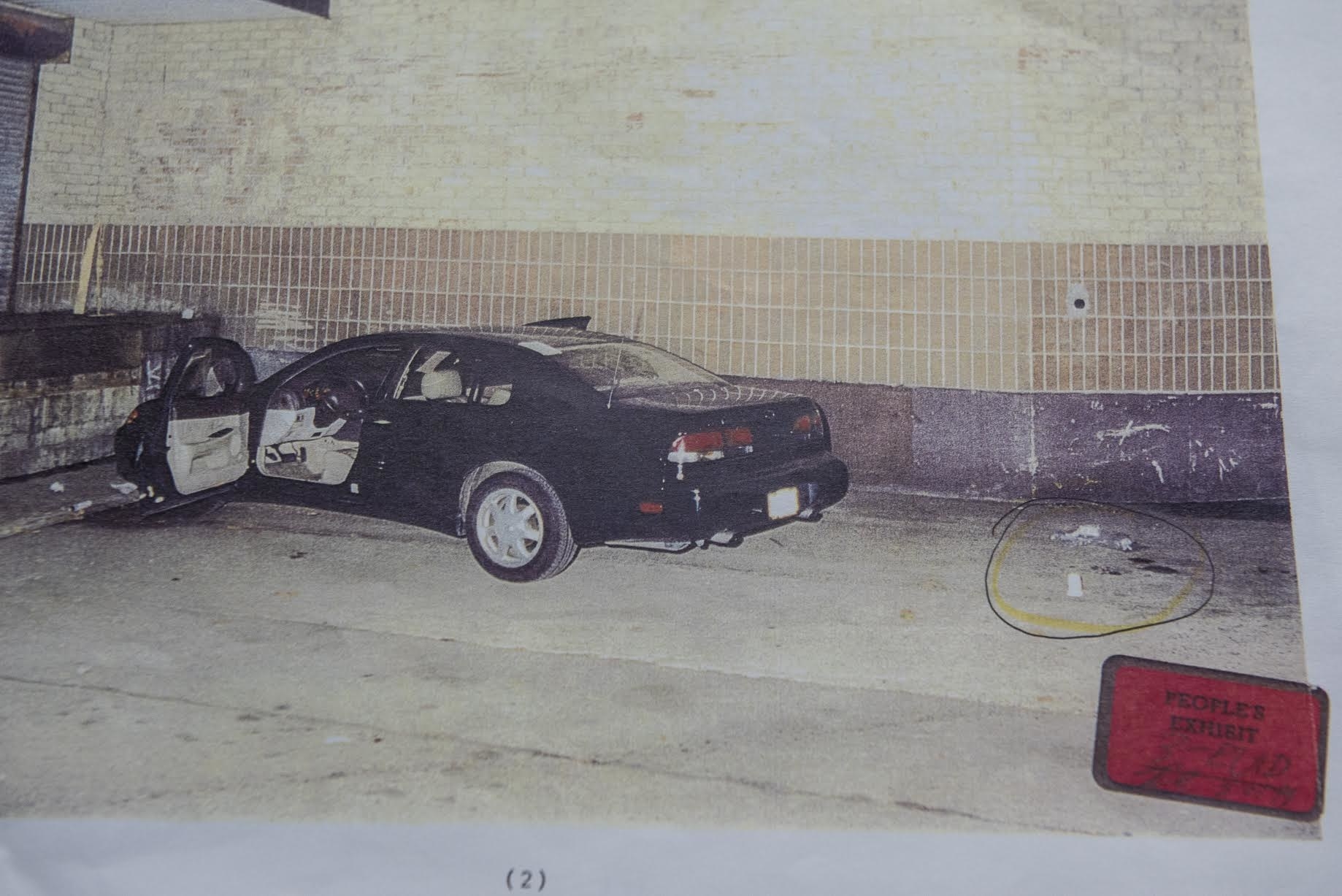

By the time anyone called 911, Michael Ledeatte was bleeding to death in the driver’s seat of a stolen Lexus parked on a dark loading dock behind a grocery store in the Bronx.

“He’s my friend. He’s been shot,” Greg Walker told a 911 dispatcher from a payphone nearby at 2:40 a.m.

Detective Joseph Nieves, a veteran of the New York City Police Department, picked up the case that night in September 1996. Within 72 hours, he’d closed it by arresting a 26-year-old named Antonio Mallet, who was convicted at trial and went on to spend 20 years in prison for the crime.

Mallet’s conviction rested on Walker’s account that he had seen Mallet fire the gun. But now, in an affidavit filed Wednesday, Walker claims that testimony was a lie. NYPD detectives from the Bronx coerced him into framing Mallet for the crime, he said, by threatening to send him to jail unless he pinned the murder on the used car salesperson with no criminal record.

In his affidavit, which was signed under oath, Walker stated that he repeatedly told officers he hadn’t seen who shot his friend. But detectives wouldn’t accept that. They told him Mallet was dangerous. They told him they had other evidence against Mallet. And they told Walker that if he didn’t tell them what they wanted to hear, he was the one who would wind up behind bars.

Mallet filed Walker’s account in a New York state court this week as part of an effort to overturn his conviction based on new evidence. Now 49, he was released on parole earlier this year and said he is trying to rebuild his life and hopes the new affidavit will convince a court to help “get my name cleared and exonerated, get my life back.”

“All I want is the truth,” Mallet added.

For his part, Walker said he was coming forward now because he finally wanted to do the right thing after years of trying to forget the past.

Also bolstering Mallet’s case is another affidavit filed alongside Walker’s in which another of the murdered man’s friends, Kelvin Rosado, swore under oath that Nieves tried to force him to claim he had seen Mallet and the victim arguing, which wasn’t true.

A third affidavit, from Geoffrey Loftus, one of the country’s leading experts on memory and perception, determined that it would have been virtually impossible for anyone to make a positive identification of the shooter from where Walker said he was standing — 140 feet away in the dark.

The NYPD declined to comment for this story. Detective Nieves, who left the force shortly before Mallet’s case went to trial in 1999, also did not comment. When reached by phone in December 2016, he hung up. He did not respond to subsequent messages, a letter delivered to his listed address, or a note passed along by the NYPD detectives’ union this week.

The Bronx District Attorney’s office, which prosecuted Mallet, also declined to comment on his case. But the prosecutor’s office added that it had created a dedicated unit in 2016 to investigate claims of innocence and allegations of misconduct. “We hope to inspire prosecutors around the nation to do the same – look for and find wrongful convictions,” a spokesperson said.

Mallet’s case could add to mounting scrutiny of the NYPD in the wake of a BuzzFeed News investigation that revealed how hundreds of officers kept their jobs after committing serious offenses — from lying to grand juries to attacking innocent people.

The Bronx District Attorney’s office has for years had one of the highest rates of wrongful convictions per capita among large counties, with mistaken witness identification and misconduct by police or prosecutors among the top contributing factors, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

Mallet’s case also underscores the challenges of addressing allegations of past wrongs in the American criminal justice system. In recent years, exonerations as a result of DNA evidence have garnered a great deal of attention. But inaccurate eyewitness identification is a major factor in many wrongful convictions. And in some ways it’s a tougher problem to address than cases that rest on DNA: While research has proven that such identifications are unreliable under certain circumstances, false identifications cannot be sent to a lab and tested the way a DNA sample can help definitively prove someone’s innocence.

BuzzFeed News first heard of Mallet’s case four years ago when he sent a letter to reporters alleging that police had failed to do a thorough investigation before deciding he was guilty and asking journalists to look into his case.

Michael Ledeatte was murdered during what was supposed to be the handoff of a stolen Lexus. He dealt in stolen cars and had made a plan to meet a buyer in the deserted grocery store parking lot in the early morning hours of Sept. 24, 1996, Walker said.

Walker was supposed to give his friend a ride home after the deal was done. He followed him to the scene but got stuck at a red light. When Walker pulled into the lot around 2 a.m., a few minutes behind his friend, he saw one man standing next to Ledeatte and another walking up from a white car parked nearby. Walker decided to hold back about 150 feet away and wait for his friend to finish.

He saw one of the men, who was wearing a hoodie, lean into the car where Ledeatte was sitting. Suddenly, there was a pop and the two men ran to the white car and took off.

Walker drove up to the Lexus and could see his friend was bleeding and his body was twitching.

He drove to the front of the parking lot to find a payphone and called 911. “He doesn’t look like he’s alive,” Walker told the dispatcher, sputtering out details as he tried to catch his breath.

Within minutes, the scene was swarming with officers. When police asked him what happened, Walker’s story kept changing, according to police reports.

Three hours after the murder, at 5:30 a.m., Walker told an officer he hadn’t witnessed the murder. Shortly afterward, he signed a written statement to that effect, witnessed by Nieves and another officer.

But police did not release him. They continued to question him throughout the day, according to his affidavit. By 8:30 p.m., Walker was exhausted. The detectives had informed him he was a suspect and had told him he had the right to remain silent. But Walker kept talking.

After hours of interrogation, he began to give police more details about how he had helped Ledeatte with his stolen car business, picking him up on at least five other occasions after he delivered cars to buyers, according to a statement he gave Nieves and another detective, Donald Gannon. (Gannon died in 2004.)

Walker also told police he’d previously seen Mallet talking to his friend, Ledeatte, at a car salvage yard in the Bronx and thought he might be buying the stolen Lexus. But at that point in the interrogation, Walker was still maintaining — falsely, he now says — that he hadn’t seen the shooting.

The detectives kept pressing him. Eventually Walker’s story shifted again. When he finally told them he’d seen a man shoot his friend but didn’t know who he was, the detectives got angry and said he was still lying, according to Walker’s affidavit.

Walker said that one of the two detectives who interviewed him got violent then. Walker didn't identify the detective by name in his affidavit. Police records indicate the two detectives who interviewed him were Nieves and Gannon. “The detective grabbed me and pulled me out of the chair I was sitting in. He slammed me up against the wall, which was painful and scared me. The detectives said I was going to tell them who did the shooting or I was going to jail,” Walker said in his affidavit.

He said he told the detectives again and again that he didn’t know who the shooter was, but they kept at him for hours, according to his affidavit. They told him Mallet had a long criminal record — which was not true, according to court filings. And they told him that Walker’s statement would merely be supporting other evidence they already had — which also wasn’t true. Walker felt like there was no way out but to tell them what they wanted to hear.

At 10:30 p.m., about 20 hours after the murder, Walker changed his story yet again. He claimed that he had seen the shooter. And, he told detectives, it was Mallet. The detectives suddenly relaxed and got friendlier, Walker said in his affidavit. He signed a statement pinning the crime on Mallet, and they let him go home.

Shortly afterward, Mallet heard the cops were looking for him and voluntarily went to the precinct to see what the problem was.

“I didn’t have a clue,” Mallet said. “When you commit a crime, you don’t want to go to the cops. You’re trying to get away.”

He was put in a lineup. Walker pointed him out as the shooter, and Mallet was eventually charged with murder, records indicate.

Nothing in records provided by the Bronx District Attorney’s office or the NYPD indicates that Nieves investigated other people who may have had a motive to kill Ledeatte or tried to find the second person Walker described fleeing the scene.

And there is no record that detectives checked Ledeatte’s beeper to see who he’d been in contact with or examined other physical evidence to determine if Mallet could be tied to the crime.

Instead, detectives went about finding evidence against Mallet and in at least one case tried to pressure someone else to provide it, according to the affidavit filed this week from Ledeatte’s friend and an acquaintance of Mallet’s, Rosado.

Rosado isn’t sure how Nieves got his name but thinks the detective must have gone through the guest book at the funeral and then asked him to come to the precinct.

Rosado had known both Ledeatte and Mallet from the used car business. According to the affidavit, Nieves insisted Rosado had seen Ledeatte and Mallet arguing at Alpine Motors, Rosado said, even though Rosado told the detective he’d never seen Ledeatte and Mallet together there. In his affidavit he claims Nieves kept pressing him on the issue, trying to get him to say that he’d seen an argument. As the detective yelled at him, Rosado continued to tell him that he’d never seen anything like that. Nieves stopped when he heard that Rosado’s lawyer had arrived at the precinct, Rosado said.

At trial, the Bronx prosecutor didn’t present any evidence — other than Walker’s testimony — that Mallett was involved in illegal activity or that he even knew Ledeatte. It turned out Walker’s testimony was the only evidence against Mallet.

After only a few hours of deliberation, a jury convicted him and he was sentenced to 20 years to life.

Ledeatte’s murder and Mallet’s arrest came as NYPD detectives were under intense pressure to close cases, even complex murder cases, quickly.

It was a new era in NYPD policing. Just a few years earlier, then–police commissioner William Bratton had ushered in “CompStat,” a data-driven approach to crime-fighting that pushed supervisors to track each precinct’s crime statistics “with the hawk-like attention private corporations pay to profit and loss,” according to a 1996 edition of the NYPD’s internal newsletter.

With the new program came a focus on detectives making arrests and closing murder cases quickly, usually in under three days, said former Bronx detective Peter Forcelli, who has worked to overturn several wrongful convictions since leaving the force.

That pressure also led some detectives to cut corners, he said.

Mallet’s lawyers said that is what happened in this case, with the detectives feeding Walker information to make his statements fit the crime.

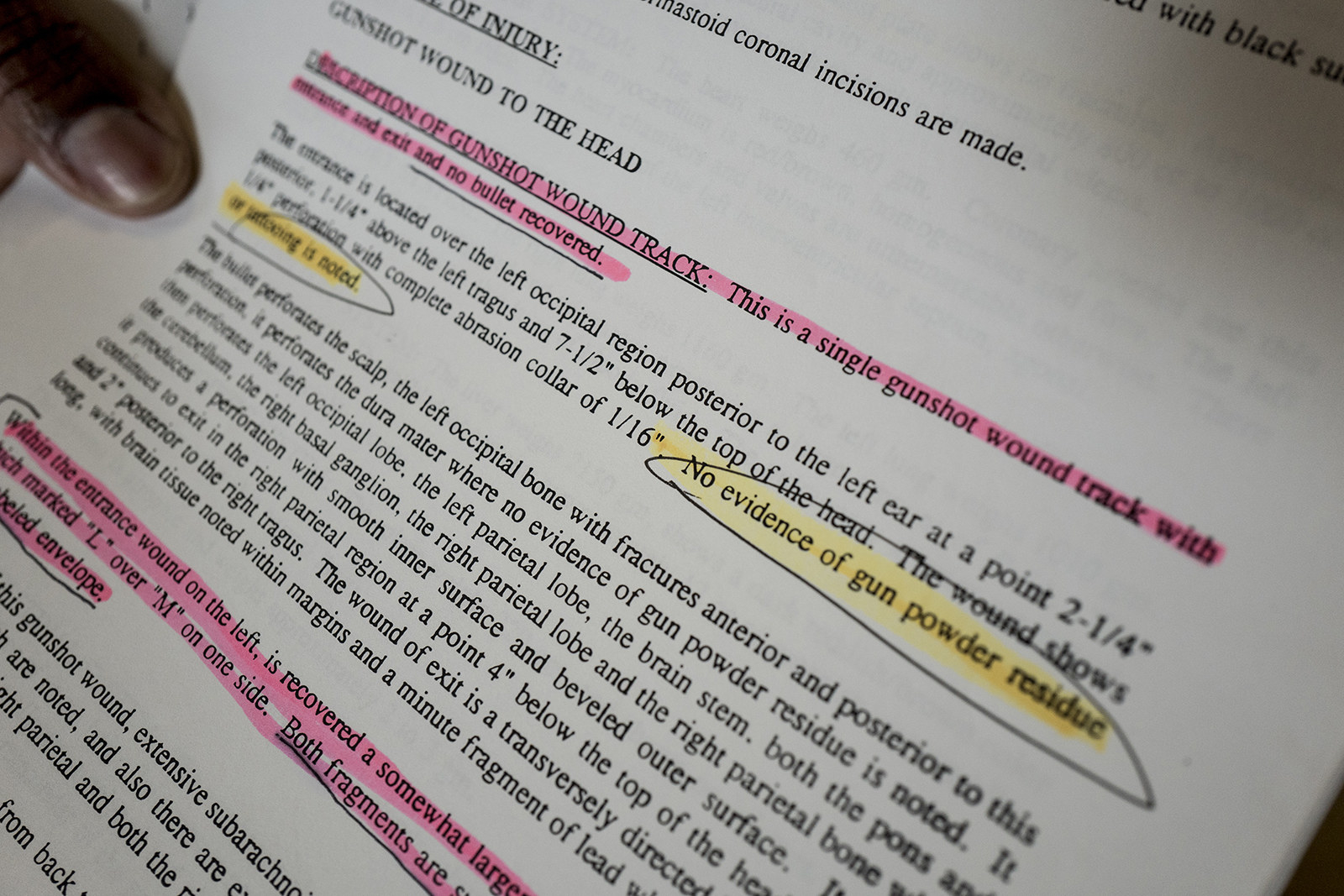

Walker had only heard the gun go off once, according to both his affidavit and his trial testimony, but that didn’t match the initial report police had from the hospital, which suggested the victim had been shot twice.

“The detectives told me different things to put in my statements,” he said in his affidavit. “I told them I only heard one gun shot, but they said there were definitely two gunshots and I needed to say that. So I put that in my statement.

Jim Trainum, a former Washington, DC, homicide detective, said this kind of contamination — when information that only the police could know creeps into a witness’s statement — is a huge red flag. “In order for the eyewitness’s narrative to be believable, it has to match the facts,” he said.

Walker, who now works as a long-haul truck driver, said he was young and vulnerable when he first encountered the detectives working on Mallet’s case. "I am a stronger person today and I can now stand up for what I always knew to be the truth," he wrote in his affidavit. “I want the court to know that I am coming forward only because I want to do what is right and set an example for other people who were put in a position of being forced to wrongfully accuse another person of a crime.”

After his arrest, Mallett said he spent the next two months in jail and then got out on bail. Almost three years passed before the case went to trial. In the intervening years, his girlfriend got pregnant. Five days before his trial began, she gave birth to their baby girl.

From prison, Mallet kept busy. He filed appeals trying to get another look at his case and estimates he sent out more than 300 letters trying to get journalists, lawyers, or private investigators interested — one of those letters arrived in BuzzFeed News’ mailbox.

Mallet was released from prison in January and has been working to clear his name. In the coming months, a judge will weigh Mallet’s request to vacate his conviction, the affidavits he filed with it and the Bronx District Attorney’s response to determine whether his conviction should be overturned.

In the meantime, Mallet is working to make sense of a world that barely resembles the one he left behind when he went to prison two decades ago.

“It’s a struggle. Nobody wants to hire a convicted felon and on top of that a convicted murderer,” Mallet said. “All I’m expecting, man, is for the system to do the right thing.” ●