Later this month new regulations around e-cigarettes come into force in the UK. Figures from last December, the latest available, show that e-cigarette use in people trying to quit smoking is on the increase, although overall growth in e-cigarette use has slowed. Meanwhile, there's been a lot of conflicting information floating around about the possible harms and benefits of vaping.

So to clear up some myths and misconceptions, here's what we know and what we don't know about e-cigarettes.

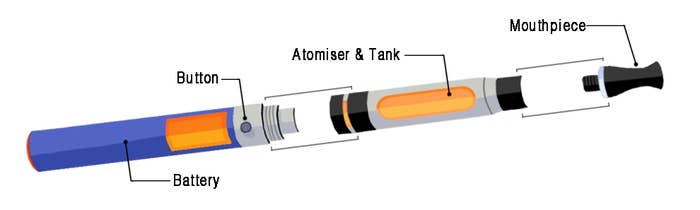

What are the main differences between e-cigarettes and tobacco ones?

What will change once the new rules come in?

The new regulations require e-cigarette packaging to be childproof, and for e-cigarettes to provide a consistent dose of nicotine and be refillable without leaking. They also limit the size of e-liquid cartridges to 2ml and the maximum concentration of nicotine allowed in an e-liquid to 20mg/ml. E-cigarettes and liquids with higher nicotine levels than that will need to be licensed as medicines and will be regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)

Do they actually help you stop smoking?

Can I get one on the NHS to help me stop smoking?

One e-cigarette in the UK has been given a medical licence already, meaning its manufacturer, British American Tobacco, can advertise and sell it as a device that helps people stop smoking. The company says it plans to launch the licensed e-cigarette, Voke, in the UK later this year.

The licensing paves the way for it to be prescribed on the NHS, although before that can happen the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence must rule that the device provides value for money.

Aren't they just as bad as actual cigarettes, though?

Are there any ways in which e-cigarettes are worse than traditional ones?

Some of the harmful constituents of cigarette smoke are present in vape too – but all the evidence so far shows that they're present in smaller quantities.

"Cigarette smoke contains about 7,000 constituents and about 70 are known to cause cancer," said McNeill. "E-cigarettes have a much smaller number of constituents – it's largely glycerin, propylene glycol, nicotine, and flavourings."

The Public Health England report from last year says that when overheated, e-cigarettes can release high levels of chemicals called aldehydes, formed when oxygen reacts to alcohols. But, crucially, aldehydes are also released in tobacco smoke. The two studies cited by the report found aldehydes were released in much lower levels during vaping – between one-fiftieth and one-sixth of that found in cigarette smoke. On top of that, if you ever tried to vape at a temperature high enough to release these chemicals, you'd get a harsh, bitter taste – what vapers call a "dry puff" – that would alert you immediately.

Because e-cigarettes are relatively new products, we don't know much about their long-term health effects. And there are other unknowns, like what happens to the flavourings used in some e-liquids when they're heated and inhaled.

A report from the Royal College of Physicians published last month said: "Although no study so far shows any clear hazards of flavours in e-cigarette vapour, those derived from flavours seem the most likely to pose appreciable health risks from long-term use."

"We need to keep an eye on the products and how they're made, and if we can make them even less harmful," said McNeil. "But smoking is the most dangerous thing people can do, so [e-cigarettes] hold much lower risks in comparison."

I don't smoke but I want to try an e-cigarette. Is that a bad idea?

Isn't there evidence that vapers go on to smoke tobacco products later?

Some studies have claimed e-cigarettes are a gateway to tobacco, but when you look closely at the evidence, it's not so clear.

"The trouble is the people who are most likely to experiment with e-cigarettes are also the people who are most likely to experiment with cigarettes," says McNeill. "Studies that show that somebody uses an e-cigarette and then goes on to smoke don't necessarily show that it was the cigarette that caused them to smoke. They may have just been more likely to take risks anyway."

And the numbers of people who have never smoked and use e-cigarettes is very low to begin with. The most up-to-date statistics we have on smoking in the UK show that less than 0.5% of adults who have never smoked use e-cigarettes. That's roughly about the same proportion of adult never-smokers who use other nicotine replacement therapies, like gum (which apparently is a thing some people do).

Will e-cigarettes lead to more children and young people taking up smoking?

Are there any harms from second-hand vapour?

Should e-cigarettes be banned in public places, like smoking has been?