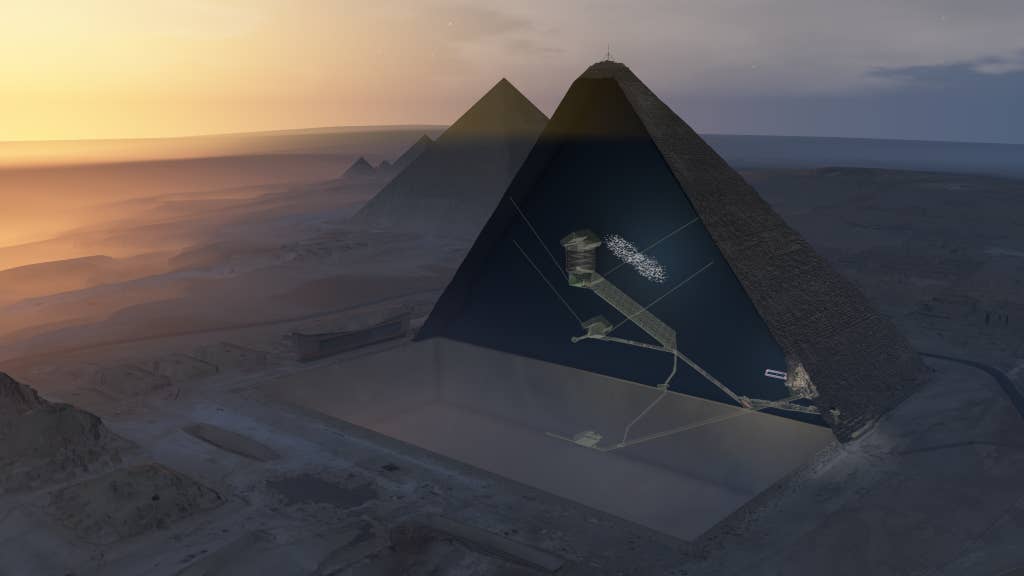

Scientists have discovered a big void in Khufu's Pyramid, the largest pyramid in Giza, Egypt. It's one of the oldest and biggest monuments on Earth – but exactly how it was built is still a topic of debate.

The pyramid was built during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu from 2509 to 2483 BCE. The newly discovered void in it is at least 30 metres long and sits above what's known as the pyramid's Grand Gallery. The research is published today in the journal Nature.

A team of scientists made the discovery using particles that are produced naturally in the upper atmosphere, as by-products of cosmic rays that come from space. These high-energy particles, called muons, take different paths depending on if they're travelling through air or stone. Muons made by cosmic rays are around us all the time – if you held your hand outstretched in front of you, on average one muon would pass through it every second.

“The thing is, when they cross materials they actually lose energy, and when they lose energy they stop and decay,” said Sébastien Procureur, one of the authors of the paper and a nuclear physics researcher at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission.

“If you have a muon detector behind or below an object that you want to probe, you just count the number of muons that are coming from one direction.”

This count then gives you an idea about the density of the object the muons have travelled through – that's how the researchers found this big void in Khufu's Pyramid – also known as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The team used three different muon detection techniques to figure out how the muons were affected by having travelled through the pyramid, and waited until all of their three groups had independently detected it before announcing their discovery.

The finding could eventually shed light on how the pyramid was built – although it's still early days, as the researchers haven't yet figured out the exact orientation of the void.

“In order to understand how Khufu was built, we need to understand the internal structure. By detecting a new void in the pyramid, it could help identifying the different steps of construction,” said Hany Helal of Cairo University, another author of the paper.

“Having said that, we should be very cautious at this point of going too far beyond the observation of the void, because at this point it needs more research and identification of its orientation and dimensions.”

The imaging technique has already been used in other situations, including at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan and to observe the chamber of a volcano.

Chris Gaffney, head of archaeological and forensic sciences at the University of Bradford, told BuzzFeed News the paper was interesting as pyramids are “frustratingly difficult to investigate”.

He added that using the technique to investigate other pyramids could help reveal their significance: “This work has the potential to convert locally important monuments into internationally important sites.”

And there are similar sites across the world where this technique might be useful, said Gaffney: “While the applications in heritage terms are probably limited to pyramids, the application of the technique may well be expanded over time.

“Particularly I would suggest that structural integrity of monuments in areas where natural disasters occur could be investigated. The integrity of such sites are often an important part of post-disaster rejuvenation, particularly in drawing tourists back into an area.”