PARK CITY, Utah — One day, should someone venture to tell Rick Famuyiwa's story, it might go a little something like this: A kid from Inglewood, California, who didn't quite fit in gets thrown a curveball in college, deciding to forgo a career in political science to instead try his hand at telling the types of stories that often don't get told, mostly set in his old neighborhood.

And when the curtain gets peeled back a bit more, they'll discover that Famuyiwa loved Nine Inch Nails, Tony Hawk skateboards, and building half-pipes out of discarded materials.

You know, shit white people like.

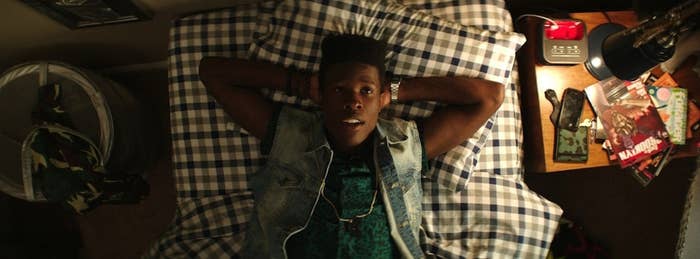

But until that happens, it would be easier to check out Famuyiwa's latest film, Dope, which centers on protagonist Malcolm (Shameik Moore), the most autobiographical character Famuyiwa (The Wood) has crafted yet, and which introduces the audience to people rarely seen on a big screen before, if ever: Nerdy black kid Malcolm dreams of attending Harvard while trying not to get his ass kicked for his new pair of sneakers; Jib (Tony Revolori), his racially unidentifiable homeboy, feels comfortable using the n-word in nearly every sentence; and Malcolm's lesbian BFF Diggy (Kiersey Clemons), who, when her family tries to pray the gay out of her, sneaks a peek at one of the sexy parishioners communing for her salvation. Together, the three are inseparable — even when getting jumped by the school's heavies – and they're bonded by their obsession with '90s hip-hop, Donald Glover, and getting good grades — what the narrator (and the film's Oscar-winning producer) Forest Whitaker says is "shit white people like."

That Famuyiwa even got his latest effort made — it is one of the most successful films to come out of the 2015 Sundance Film Festival so far, with Open Roads/Sony purchasing it for a cool $7 million while guaranteeing to spend an additional $15 million to market the film — is itself noteworthy. The film is a homage to Famuyiwa's love affair with '90s films, and the lead character is molded from Famuyiwa himself.

But that doesn't mean that getting Dope — which was hailed by critics as "bouncy, with snappy dialog" and filled with "playful energy and wit" — made was easy.

"Oh, it was very challenging," Famuyiwa told BuzzFeed News. "None of the studios we took it to could understand it. They looked at it and it didn't fit neatly into a box that they could understand. These kids are dressed like the '90s, but it's set in present day. They're talking about bitcoins, but they live in the 'hood. They couldn't wrap their brains around what we're trying to do."

If you've followed Famuyiwa's career, this is hardly a surprise. The 41-year-old director is best known for telling coming-of-age stories rarely told in Hollywood. 1999's The Wood introduces three young black male friends (Taye Diggs, Omar Epps, and Richard T. Jones) who live in a working-class neighborhood sprinkled with crime and salty behavior. That coming-of-age story demonstrated how, in spite of some challenging odds, these young men all kept their eyes on the prize, fulfilled their dreams, and learned when to grab a handful of female booty at the middle school dance. And in 2002, he directed the now classic rom-com Brown Sugar, about two childhood friends (Sanaa Lathan and Diggs) who grow up to be a music journalist and a music producer and who, after other failed romantic mishaps, realize they're in love with each other.

His latest, Dope, was one of several films at this year's festival that offered a compelling and distinctly black story. The film is rounded out with a fantastic young cast, including Zoë Kravitz, A$AP Rocky, Chanel Iman, and Blake Anderson. That it was as successful as it was — it entered a six-studio bidding war before settling on Open Roads two days after its premiere — is major.

"There's a certain way films with black characters are perceived and the types of stories that get made, but I wanted to do something that was me, and not try to follow something else," said Famuyiwa. "After I did my last project [2010's Our Family Wedding], I felt like I had gotten so far away from my original voice."

Famuyiwa made the film outside of the traditional Hollywood system, but with some major assists: Superstar music producer Pharrell Williams provided new music — the kids are in a punk band together — and hip-hop mogul Sean (Diddy) Combs' Revolt imprint is listed in the credits. But even with such high-profile participants, Famuyiwa is determined to go at it on his own road, which is a harder climb than it is for many white filmmakers.

"I got to the point like I'm going to do this no matter what," he said. "When you're making films with people of color in them, when they come out, each one has to almost speak for the entire race if you're a person of color. And that's the responsibility that most artists don't have to deal with. It's not something Alexander Payne or Steven Soderbergh or Wes Anderson have to worry about — how is my film going to be perceived racially? It's the kind of thing that filmmakers of color and women and other folks who aren't just white men have to deal with in the business."

"It's so rare that you get to see these representations," he continued. "It takes on a larger role than a movie. For me, I had to shed that fear of whether things would be perceived right, or certain folks would think things are too taboo. I just had to follow these characters and make sure I was true to that. I got to a point where I stopped caring about that, and cared more about the artistic expression that I needed to figure out."

Still, to say that Famuyiwa is surprised by Dope's early Sundance success is an understatement. He says his writing voice is weird, and the story doesn't conform to expectations. It won over an audience that is in love with film generally speaking, but the true test — and Famuyiwa is well aware of this — is getting it out in front of a larger audience. It's why negotiating that hefty marketing budget was key.

"I wondered what the reaction would be. But when I was writing this, I believed it was something that could connect at any level. Race is one very small part of who we are — we have other ambitions and similar struggles and we're all Americans, so we have a similar sense of humor as well," Famuyiwa said. "I was confident that it would play well. But it's still an exhale moment when people are actually reacting like I hoped they would. The hug that we're getting from all of the audience feels good."