It was our first-ever couple’s getaway. Albert and I were set up in an all-white seaside hotel room in the tony San Diego suburb of La Jolla. At our disposal was a California king bed, a Jacuzzi, spa-fluffy robes, and best of all, a fairly fat expense account — all of which helped to make up for the escalating abdominal pain I experienced throughout the stay.

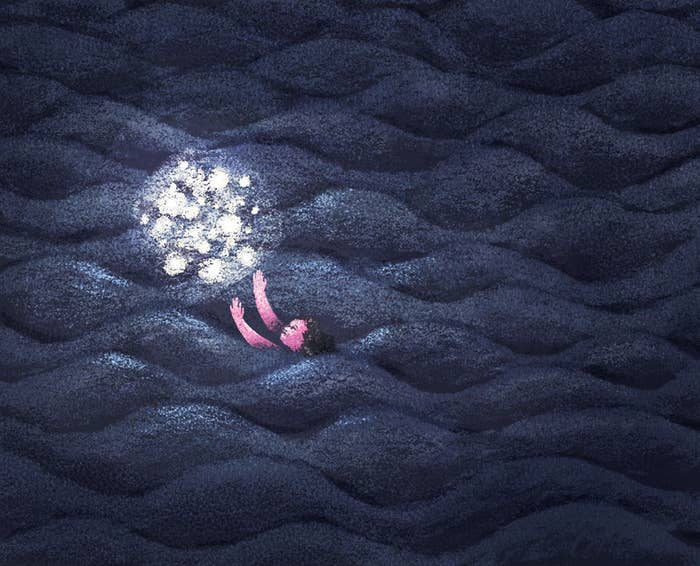

As an egg donor jacked up on a superdose of fertility drugs, I reached new heights of being bloated and horny that weekend. I was also operating on the emotional wavelength of a toddler, raging over a forgotten magazine one minute, and in the next melting into tears over the adorable sea lions that performed impromptu diving shows all along La Jolla’s shoreline. In hindsight, it’s possible I was overidentifying with the sweet, bewhiskered blobs — I could barely squeeze into my fat pants. I was a far cry from the companion visiting most men’s “sexy sojourn” fantasies.

But Albert (his middle name) was technically my plus-one, fulfilling the role of the driver’s license–holding pal that my egg donation agency required present for the final act of donorhood — ovum retrieval. This is the part where a reproductive endocrinologist sucks biogenetically multiplied eggs out of a donor’s anesthetized pelvis, fertilizes them, and implants them into the uterus of another woman, or “birth mother.” The objective is to impregnate the latter with the former’s biological baby.

My procedure was scheduled to take place on the fourth and final day of our stay. Each afternoon leading up to retrieval day, I had to strip from the waist down and get penetrated with a probe that felt like an ice cube. The doctor whom my agency contracted to collect their stock used these sessions to monitor the sizes and counts of my eggs. After each ultrasound, he would announce, in a barky Israeli accent, how “close to ready” these eggs were for the task of launching new life. Which meant I had to stick close by his clinic; hence the egg broker–sponsored hotel room and per diem dining allotment.

The year was 2009. I was 25, disastrously broke, and determined to live it up with my long-distance sort-of boyfriend as if this were all some carefree jag that Albert and I could actually afford. By the time we checked into our free hotel room, I’d been off birth control for 21 days. Almost two weeks’ worth of fertility drugs coursed through my veins. My fecundity, I was told, was at its all-time peak.

I was also experiencing the type of cramps that make the worst menstrual aches feel like tickles. My ovaries had ballooned in size, leaving little room for anything else to comfortably exist within my torso. Suffice to say, intercourse was a challenge.

This situation translated to junior high–style petting, oral sex marathons, and a couple of instances in which I managed to cajole über-cautious Albert into sliding in for fleeting moments of pleasure. Before we could ever get a good thrust in, though, I’d yelp, wondering whether it was possible to literally burst at the seams. Each time, he’d retreat, cupping my chin and begging, “Please, Katie, you don’t want to hurt yourself at this point. Let’s just take it easy.”

This notion, however, proved the opposite of easy — I lived in L.A., and he in Chicago; it was rare to be able to spend four nights in the same city, let alone the same bed. But still, I would usually stop pressuring us both and reserve my vaginal bravada for the next probing. Albert and I would just spoon, or maybe get more gelato, before succumbing to 10-plus hours of black sleep.

In the morning, I’d bare the top corner of my left buttcheek for the prick of a Follistim-filled syringe and, before I could even wince, a kiss on the same spot. During the trip, Albert, a trained emergency medical technician and social worker, took over the administration of my twice-daily fertility shots. Days passed through excessive meals, sea lion–gazing, and geriatric-paced strolls through town before we had to report back to the hotel room — always by 9 — for my p.m. dose of Follistim.

Still, I was desperate to parlay this agency “observation period” into some romantic rendezvous with my newly on-again long-distance paramour. I wanted the whole thing to feel aphrodisiac, exciting — the equivalent of a decadent getaway with a mistress. According to this drug-induced logic, however, the actual mistress in the equation would’ve been the facilitators of my unborn child; i.e., the industry of assisted reproduction.

Whereas Albert was careful, caring, and calculating, egg donation was thrilling, enigmatic, potentially dangerous. It caused me to act secretive, cagey. It lavished ego-boosting praise — agency coordinators were always fawning over my curly hair, my “runner’s body,” my degree from a top-ranked university. Whereas Albert and I started sleeping together soon after meeting, egg donation had showered me with gifts of agency-branded chocolates and Starbucks cards, and promises of riches — eight thousand taxable dollars — before even moving to get into my pants.

I took up with egg donation soon after moving away from Chicago, away from Albert, in pursuit of a sunny new existence in Hollywood. I’d gone west with friends, fellow twentysomethings chasing vague, showbizzy writing whims. If anyone asked further questions, I would explain that Los Angeles exerted a “psychic pull” over me. Becoming a surrogate ovulator was never part of the original plan.

Just 10 weeks before my date of West Coast departure, I had caught sight of Albert’s enormous pale blue eyes in the dim of our shared neighborhood bar. At the time I was accustomed to dating self-involved, alcoholic poet types. Once I worked up the courage to approach Albert, I found his intense, straightforward nature even more arresting than his eyes and experienced a tingly rush when he asked me out for ice cream. Things quickly escalated into what I thought was a steamy, pre-relocation fling. After I went through with the move and we technically broke up, though, we stayed in daily communication. He sent handwritten letters and thoughtful little gifts in the mail. Being lonely, and being fonder of Albert than I’d been comfortable admitting before moving away from him, I welcomed these gestures. Despite the nebulous, sort-of status of our relationship, I invited him out to celebrate my first holiday away from home and family — Thanksgiving of 2009.

A few weeks before this visit, however, I celebrated my 25th birthday too hard. More specifically, I downed cheap champagne to the point of blacked-out oblivion and fell down outside of a hip L.A. bar, smashing my head onto the sidewalk and knocking myself unconscious. When I awoke the next morning, my arms were hooked to several IVs, and I was harboring a catheter. After finding out I’d been chauffeured, via ambulance, to the emergency room of Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital, I panicked to the point that I actually stopped breathing. At the time I was working as a TV development intern by day and a cocktail waitress by night — a totally uninsured one. I was poorer than I’d ever been in my life.

A thwarted attempt to escape the ER undocumented ended in tangled IV cords and gurney restraints. Because I’d lost my phone in the drunken calamity, I couldn’t call anyone — much less Albert, who might’ve actually been able to temper my clinical-grade panic. With an official diagnosis of “mild concussion and alcohol poisoning,” I was released from the hospital.

Sobbing and shoeless — my heels had gone the way of my cell phone — I navigated my way back to my rented bungalow attic via the public transportation system I was still getting used to (I was too broke to have a car) and, once home, fell into a deep sleep. When I awoke, it was still my birthday, but the sky was dark and my hair was soaked from the ice pack I’d been instructed to strap to my head. All I was capable of thinking about was the surely monstrous bills headed my way. I could barely operate my toothbrush, much less my computer, but somehow managed to perform a Google search for “fast, immediate cash.”

After wading through a slew of Craigslist ads seeking plasma donors, I finally hit upon a gig that sounded promising: “Extraordinary females” with “high SAT scores, athletic backgrounds, and emotional resiliency” were being sought to “make someone’s dream come true.” My pulse quickened as I read on to learn that for this “most special contribution” of some hyperstimulated ova — i.e., “donated” eggs — females who matched such a description could earn a check for $8,000.

This wasn’t the first time egg donation had caught my fancy. As a broke college waitress, I’d applied to a different agency on a whim. However, I’d answered their screening queries with overly honest naïveté — sharing details about my left ovary’s tendency to get obscured behind endometrial scar tissue in ultrasounds, my great-aunt’s suicide, and the fact that I am occasionally angered to the point of considering violence — and was swiftly rejected. Being a few years more savvy — i.e., better versed in the social media tricks so many of us have learned to employ to rose-wash our lives, now that we’ve entered the 2010s— my concussed, 25-year-old self vowed to make the egg brokers clamber for me this time around.

Picture a hungover mess of hospital bracelets, bruises, and E.R. bedhead applying to become someone’s genetic mother. In my dusty attic bedroom, I clacked away at this “preliminary donor survey,” inputting my sisters’ heights and eye colors, my grandmothers’ blood types, my grandfathers’ causes of death, and my attempts at descriptions of my own hopes, dreams, and temperament.

Impaired as my brain cells were, I apparently aced the questions. Within a week, an agency claiming to be Southern California’s “premiere” wrote me to request photos depicting my development from infancy to adulthood, as well as current shots, and detailed accounts of my own skills and interests.

Yes, egg donation saw something desirable within my broke, underemployed self. Already, I was swooning.

This only increased when the agency invited me in for the next phase, an “ovum acceptance interview.” For this I had to bus out to a Victorian mansion in L.A.’s suburban San Fernando Valley to meet with the sweetly beatific agency directors. These women invited me to talk endlessly about my background, as well as my “drive to donate.” As I blabbered — whitewashing the foibles of my dysfunctional family and generally trying to come across as earnest, bright, and compassionate — I prayed they wouldn’t suspect that I was solely after their money.

The women repeatedly commended me and my “spirit of giving,” and already, I felt smitten with them. But still, throughout the meeting I couldn’t stop picturing those hospital bills that had begun to pile up on my kitchen table.

Also looming large in my mind? Albert. Though we were speaking regularly, I hadn’t worked up the nerve to tell him about how I planned to pay for my brief stay in the hospital.

A close friend — I had shared my egg-ventures with few — had speculated that I was, in essence, biologically cheating on Albert. According to this conclusion, things were indeed heating up with the concubine.

A couple weeks before his pre-Thanksgiving arrival, I got a call from the agency’s bubbliest associate. She told me that a “beautiful match family” had bid for my eggs — meaning that an infertile couple had expressed interest, as well as a willingness to pay the $8,000 to $10,000 it typically takes to buy a donor’s eggs. This means the donation agency staffers had checked over the waivers I’d agreed to and signed my DNA over. When I heard the news, a tidal wave not unlike sexual thrill washed over me. All I had to do next was text this woman the moment, “the instant,” my next period began — and then they’d go ahead and get this process, the one of conjoining my “benevolence” and “great genes” with a wannabe parent, rolling.

For once, I couldn’t wait for that time of month. Anytime I sensed any moistness in the panty region, I would excuse myself to run to the bathroom and inspect myself. The day I was finally gratified with the sight of real blood, I was at a restaurant with friends — friends who didn’t know about my accident, nor my donor aspirations. The act of covertly rushing into a bathroom stall and blasting off a text message to “Nina Egg Donation” got me more excited than sexting ever had.

Nina called immediately — no game-playing on egg donation’s end. She arranged a meeting — with a Beverly Hills doctor — and sent me a little something in the mail: a packet of birth control pills that would serve to sync my cycles with those of my future offspring’s anonymous birth mother.

Around this point, emails from the agency became more arduous. They were almost always addressed “Dear Donor Angel.” The enthusiasm seemed a little over the top, sure, but I wasn’t one to argue with anyone who considered me a “godsend.” The birth parents, for their part, shipped me a gift certificate to a Los Angeles–based chain of day spas. To the world, I was just another broke recessionista, irresponsible and poorly prepared for adulthood. But in egg donation’s eyes, I was a wunderkind, a beautiful pageant princess. A winner.

Meanwhile, the status of Albert’s and my relationship remained ambiguous. Still, during the days leading up to his arrival, I fretted over how he might respond to the fact that I was ovaries-deep in the process of selling my genetic material to someone else.

It wasn’t until we were a few hours into the reunion that I finally worked up the nerve to tell him there was someone else. We’d finally emerged from my bedroom to seek sustenance at a hole-in-the-wall Thai restaurant. Employing the agency-patented “donor angel” angle, I began, “So, baby, there’s this family that really, really wants a baby. But they just can’t conceive.”

As I took him through the logistics of donation, Albert’s sky-blue wolf eyes shone. He looked at me as if I actually had a halo shooting out of my skull. Donation, he said, seemed like a “beautiful decision.” He actually told me he loved the notion of “little Katies” out there, populating the world. He clasped my hand over the table and assured me he would support me throughout as much of this “journey” as he possibly could from 2,000 miles away. Albert was being such a caring partner that even I felt, in offering my body to the industry of egg donation, that I was acting as some selfless martyr. I was thrilled when he agreed to act as the companion required for my retrieval procedure — the friend who would drive me to La Jolla and deal with me while I overcame the anesthesia and returned to regular life.

As I saw it, I’d be able to pay my bills, leave my genetic marker on the world, and keep my sort-of boyfriend’s ardor going strong. On that November day, everything seemed perfect.

Soon after he flew home to Chicago, though, Albert actually did some background research on my other suitor. That’s when I got the first crushing, midday email.

In it, he insisted that I was approaching the whole ordeal with “tunnel vision,” that I was needlessly jeopardizing myself, that I was jumping into donation “incredibly fast” considering it was a “voluntary medical procedure.”

A Time article titled “As Egg Donations Mount, So Do Health Concerns” had just been published. The piece questioned the lack of scientific research that had gone into the safety of donation for donors. It also suggested the potential of correlation between egg donation and cancer, and between egg donation and infertility. Albert emailed the link to this article my way, along with an all-caps message urging me to read the story "A FEW TIMES."

Convinced the damn story was no more than slow-news-day slander, I was irate. When I wrote back, I was a puddle of hot tears. I was defensive of my side of the relationship, stubborn about his previous agreement regarding our “open” arrangement. My retrieval procedure had just been scheduled, I wrote. The egg donation agency already had Albert penciled in as my surgery companion. Was anticipation of our upcoming trip to La Jolla not consuming his waking fantasies like it had been mine? Did he not care at all about the family that was counting on my assistance? Did none of this even matter to him anymore?

After expressing as much in my email, I dialed his number. When he picked up the phone, I could already hear a tremor in his voice.

“Fuck whatever is driving you to do this, and please, just give it some more thought,” he begged. “You’re under no obligation to anyone to jeopardize your health, short-term or long. If you’re that desperate to pay off the hospital bill, just ask and I’ll help. I’ll help! Please.”

Even if the naive invincibility of youth hadn’t been on my side, even if I’d agreed with him that the medical aspect of donation was a little sketchy, a little hazy, I don’t think I could’ve let the agency down — not at that point.

The truth was, I loved them, and I believed they were enamored with me. I’d even begun to buy into the “donor angel” business that had at first seemed a little absurd. Ever since being matched, I’d begun fantasizing about “my” couple. All I knew was that they were an auburn-haired pair of attorneys, a couple who enjoyed books and who’d had poor luck conceiving. I’d envision these strangers decorating their nursery, making literary baby name lists, shopping for infant outfits. Abandoning ship at this point was out of the question — I wanted someone to have my baby.

After a few more tearful fights on the phone, I gave Albert the choice of shutting up and supporting me or, if he truly couldn’t share me with egg donation, moving on from me. I credit the fertility drugs, at least partially, for that ultimatum. As soon as it left my lips, I became terrified of losing him.

Thankfully, he opted for the former option, no further questions asked. True to his word, Albert did not utter any murmur of dissent anytime I spoke with him after that, nor throughout those final days of my donorhood in La Jolla. He even seemed to get into the spirit of living large on reproductive science’s dime — he arrived with a list of local restaurant reservations he’d spent weeks culling, and each night drew us a Jacuzzi bath.

It was only after I got my supersized eggs suctioned out of my uterus, on a gray morning in January 2010, that Albert, over one last seaside brunch, told me he had begun actively planning to move to Los Angeles. I was still fading out of my anesthesia haze, still subject to the side effects of my last dose of fertility drugs, and I became so overjoyed that I cried into my crab Benedict.

Within a few months, Albert actually made it happen. He found a great job on the West Coast, bought himself a bus pass, and moved in with me. Our relationship went from murky and technology-dependent to full-time, serious, no longer dependent on Skype and cheap flights.

My liaison with egg donation, however, has a different ever-after. I guess I’d imagined they’d keep me posted on the “miracle” I helped facilitate. But after taking what it needed from me and issuing that check, the agency all but formally terminated our relationship. There were no more calls, no follow-up — no more love letters to “angel donor Katie.”

I don’t think I fully felt the sting of this spurn until a few months had passed. I sent the agency an email, desperate to find out how everybody was faring. Within three terse lines, I learned that “my” birth mother had become pregnant with triplets, but had miscarried two of them.

I was devastated. In fact I started bawling at my desk at work and ended up leaving, mumbling lies out the door about a terrible fight with my sister. Once home, I wrote the agency back, a sad, meek missive. I expressed my sorrow, and asked my formerly friendly contacts to please do me the favor of letting me know if and when the final baby made it.

I felt like a sad, needy ex.

Meanwhile, my boyfriend was more attentive than ever — especially as mysterious shifts began to occur within my body. Out of the blue, my breasts sprouted fibroid tumors that required biopsy. A few months later, my gall bladder became distended and infected. During the related ultrasound — my first since La Jolla — the techs discovered that my fallopian tubes are covered in endometrial scar tissue. In the five years since donating, my Pap smears have been consistently abnormal. But doctors just chalk it all up to “one of those things that can just happen.”

Whenever I bring up egg donation as a potential explanation for my “lady problems,” the doctor changes the subject. Yes, anytime I verbally raise the question of whether injecting myself with maximal amounts of fertility drugs during the time in life when I was likely at the peak of my natural fertility might have compromised my reproductive system, medical professionals are quick to tell me there’s zero way of knowing whether assisted reproduction could be any sort of culprit. I’ve researched online, and I’ve consulted with fellow egg donors. The response is fairly consistent: “There is no medical evidence of any long-term health risks. IVF and egg donation do not increase an egg donor’s risk for ovarian cancer, breast cancer, or infertility.” Still, it's hard to believe that all of my health problems are just a coincidence.

Albert and I just celebrated six happy years together. Sometimes we talk about having kids — each of us being 30 and neither vehemently for or against the idea. But it’s a thought that makes me nervous — after all, my periods are now inconsistent and miserable, my notions of childbearing complex. My one-time tryst with egg donation was certainly an affair to remember, but it’s one I wish my body — specifically, the thousands of cells making up my reproductive system — would just forget already.

Eggs are fertilized before implantation. An earlier version of this essay mischaracterized some aspects of the egg donation process.