The first and only time I've seen an owl in the wild was a northern saw-whet owl in a tall bush right next to the path by the lake in Central Park. As soon as I got home, I submitted my sighting and where to find the owl to a message board for New York City birdwatchers. Immediately I started getting angry responses telling me to remove my post. Apparently, I had unknowingly violated a cardinal rule of birding: Never report the exact location of owls.

While birders post exact location details to message boards for all sorts of species (especially for unusual or locally rare birds), owls are a different story. An administrator for the message board explained to me why: Owls tend to stay in one spot for a very long time, they're more susceptible to being stressed out by human interference than other species are, and lastly, they're relatively rare, so birders are especially eager to see them.

Putting out an owl alert to a listserve of local birders would be like tipping off the paparazzi that Lindsay Lohan is leaving a nightclub with no underwear. It would end with the owl in tears, driving off erratically in an SUV.

Harnessing the power of the internet has been a boon for both birders and scientists, helping them add notches to their "life lists" (the list birders keep of what species they've spotted in their lifetime) while providing valuable scientific data. But now the pendulum is swinging back the other way, and the birding community is realizing it needs a technology solution to its human problem.

Birders have embraced the internet in their own way; Yahoo groups are still active, a handful of bloggers exist, and localized rare-bird alerts still rely on people phoning in their reports. They tend to be older — the types more likely to have an email address with their internet provider in it than have to a Twitter account. However, bird-watching is one of the few pastimes where the weekend hobbyists are actually making crucial contributions to the scientific world, and ornithologists rely on this global network of amateurs.

The most ambitious online birding effort is eBird.org, a comprehensive database collaboration by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the Audubon Society. Users enter detailed information about the exact location, species, and numbers they observe. The site functions as a free way for birders to keep easy online logs of their own sightings while at the same time helping scientists by giving them the data they need about worldwide bird populations and patterns.

According to Marshall Iliff, project leader for eBird, the site gets 3 million global bird observations per month. Another arm of the ambitious project has volunteers transcribing scans of decades-old birding reports, which will result in the largest digital set of data of bird populations and provide invaluable information for researchers and conservationists.

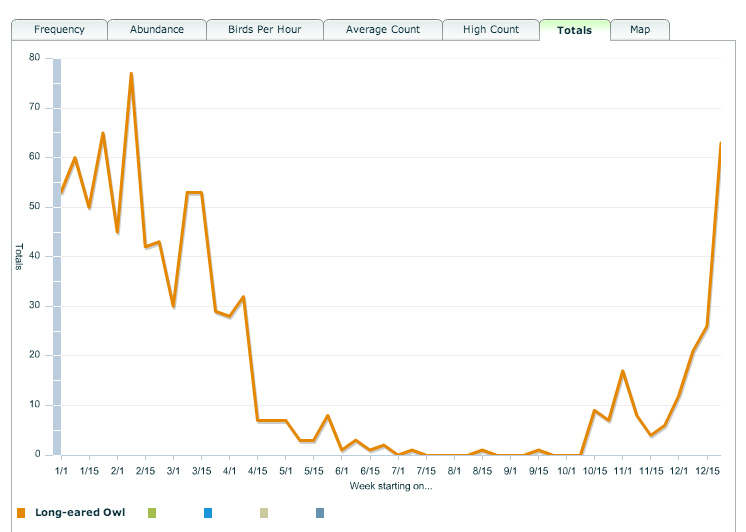

But in the world of birders, data is a double-edged sword. One of the struggles eBird is dealing with is how to handle reports of "sensitive" species, such as owls. Recently, the East Coast birding world had a near meltdown over a rumor that an owl nest in Maryland had been significantly disturbed after its location was revealed online. A report posted to the MDbirds Yahoo group said that branches had been sawed off a tree where a long-eared owl was known to be roosting. The assumption was that some unscrupulous photographer had cut the branches in order to get a clear shot (it was later determined that the branches were planned cuts for a power line).

Bill Hubick, a Maryland birder wrote in a message to the MDbirds group:

eBird, of course, has fundamentally changed how we share our sightings, with the various hourly "needs" alerts that are so popular certainly factoring in heavily in these cases. These are all very good things, and I actively support all of them. The wider net is a great thing and is not going away. That said, these technological changes certainly have a lot to do with the increased attention these Long-eared Owls have received.

Balancing transparency and sensitivity is going to remain a challenge, and self-policing what is shared, when, and how needs to be further considered.

This is far from a black-and-white issue. The "we can't protect it if we don't know it's there" argument is sound. But how do you balance that with "we know we're not protecting them when we're sawing @#$#*% branches off their roost trees"?

Another birder responded with passionate restraint, "I remember several occasions last year... a few large groups of birders were stomping down the breeding habitat of Golden-winged Warblers. I was so angry you could have fried an egg with my breath."

While many of these people have met each other out in the field as well as communicated online, the birding community can sometimes resemble a bunch of Canadian hockey dads — uneasily bound together by a common goal but ready to drop the gloves as soon as the occasion rises. There are several controversial behaviors among birders, such as playing recordings of bird songs in order to trick birds into responding (considered by some a disturbance to the birds and interference to their natural communicating and breeding habits), or willingness to trespass onto private property.

It seems that birders, people who truly care about the welfare of birds, could perhaps just tread a little more quietly while still being able to view rare birds like owls without disturbing them. But the concerns about revealing location data for sensitive species aren't just over eager nature-lovers wanting to snap a photo. There are stories of hunters who have shot rare ducks found from eBird reports, as well as falconers and egg collectors who raid nests. Egg collecting has been traditionally more of a British pastime than an American one (though it has been banned in the U.K. since 1954). In 2006, an illegal egg collector died in England when he fell from a tree while observing a nest. Two years later, Britain's most convicted egg collector was sentenced to six months in prison after being caught with 75 protected eggs, his ninth offense. A spokesman for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds told the BBC at the time they believe there are only about 50 active egg collectors out there.

Marshall Iliff of eBird explained that they are aware of the growing pains of bird privacy. "We are at a point now where the old methods — entrusting birders to report responsibly and understand the nuances of site specificity and the myriad output tools in eBird — simply is no longer tenable."

Currently, they do offer ways for users to choose to publicly hide location information if they are filing a report about their own backyard, for example. But these controls are up to the user's discretion. eBird plans on developing new tools that can hide certain pieces of data for sensitive species, like the long-eared owl, by default. Birders would still report these species, and the data would be there for researchers, but laypeople would not be able to see the location of sensitive species beyond generic county or state locations.

The birding world has reached a point in its digital maturity where it can no longer be a self-policed community. Technological infrastructure has to be set in place to protect not only birds from humans, but also to keep the peace between birder-on-birder infighting. Iliff tells BuzzFeed, "We have not planned the future developments yet, but we do have them on our long-term schedule."

In his email to the message board, he gave an example of what would happen if a species that hasn't been seen since the '60s was reported on the current site:

Bachman's Warblers are presumed extinct, but if a Bachman's Warbler is found in the Great Dismal Swamp in April 2013 and reported with site specific directions on eBird, those details will literally be available to the entire community of eBird users--even those without accounts--within an hour. While this is also true of a listserv posting, I think we can all agree that if a single pair of Bachman's Warblers remains in the world, the best thing for that species' survival may *not* be to have birders know about it.