The stranger who wrote to Lisa Daugherty had a simple question. Were the grisly details she had read about the death of Lisa’s daughter, Jessica Chambers, true? If they were, it might help solve Jessica’s murder, she explained to Lisa in a Facebook message:

“She was so burnt, her fingers were gone, her skin was crisp and falling off, her tongue was gone and she died alone wandering for help which arrived too late.”

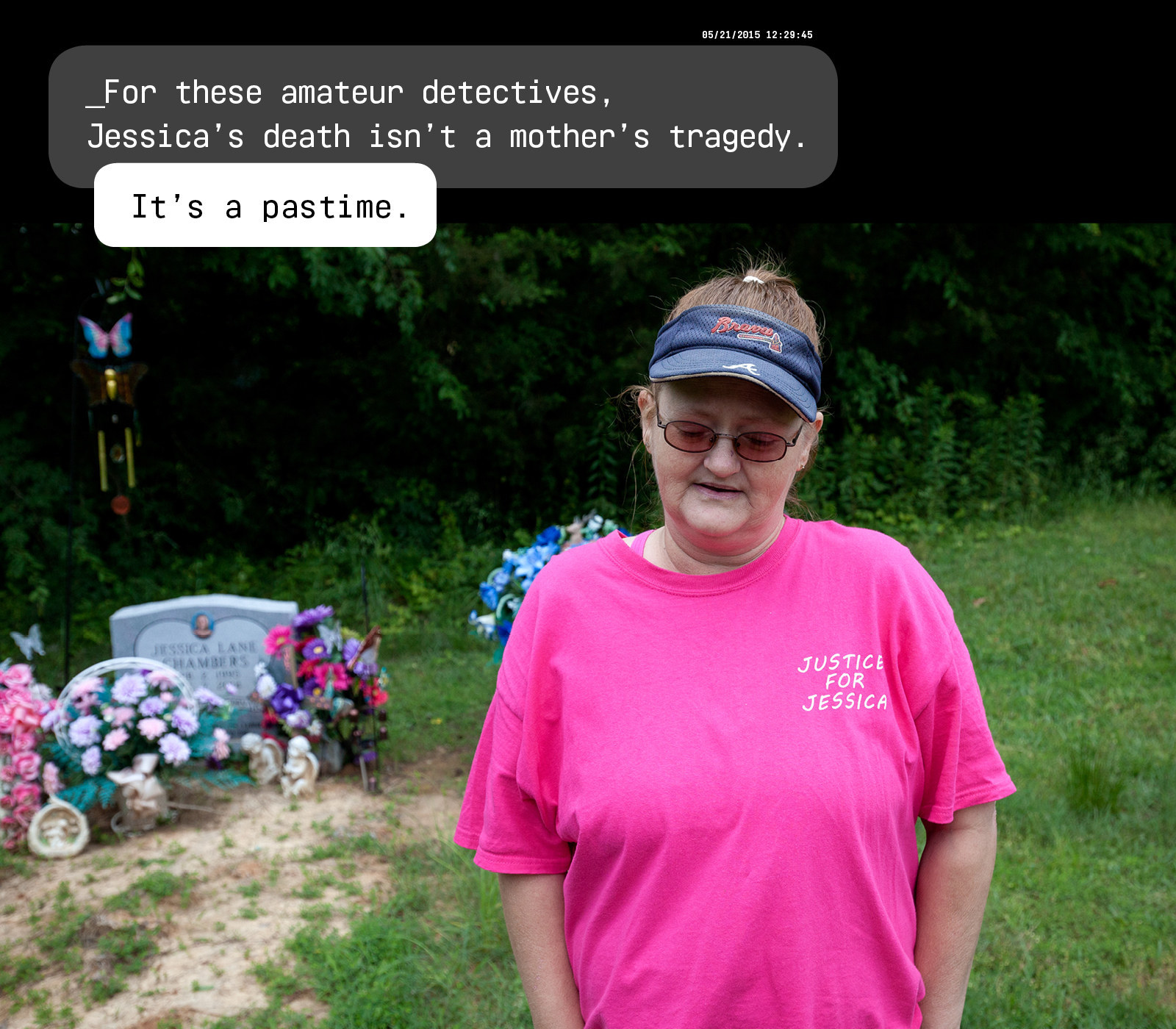

Lisa read the woman’s message aloud to me off her laptop screen in her soft Mississippi drawl. It was late May, nearly six months since Lisa’s 19-year-old daughter was burned alive in her 2005 Kia Rio on a rural road two miles from home. Lisa was spending the afternoon as she has most days since: curled up on her couch in the dark, chain-smoking and chatting with people on the internet who are obsessed with Jessica’s still-unsolved murder.

The stranger’s message didn’t faze Lisa, who was dressed in faded jeans and a pink “Justice for Jessica” T-shirt, even though it was not only grotesque but also incorrect. Lisa has heard much, much worse, both fact and fiction, since the night she sat next to her unconscious daughter, who was swaddled in bandages, and watched her take her last breath. Instead, Lisa was a bit exasperated. Facebook messages and comment notifications from other self-proclaimed sleuths she’s never met popped up as she considered how to respond.

“Well, I can tell her that I was there when she passed,” Lisa said, lighting another cigarette. “I was right there.”

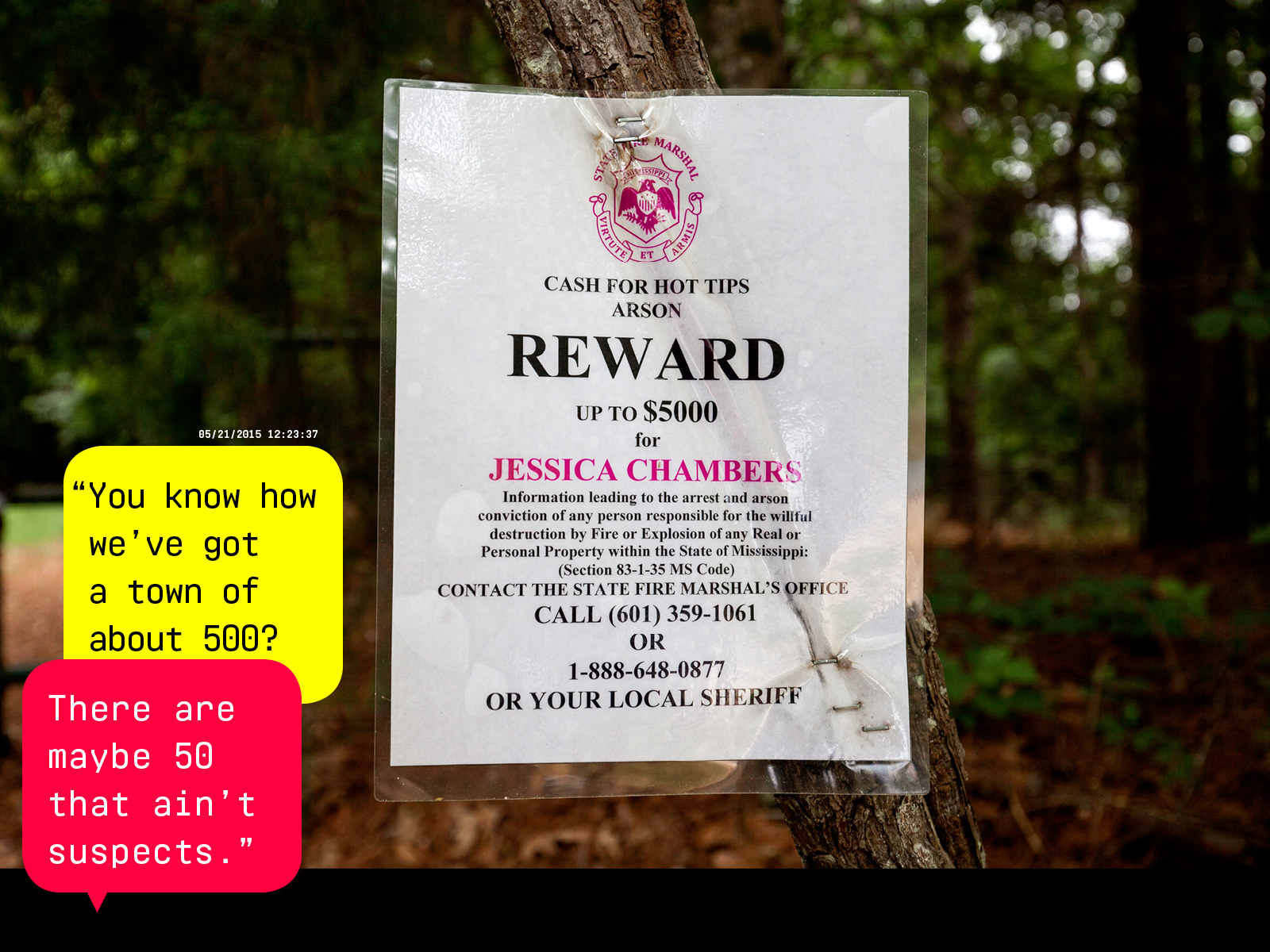

Jessica was murdered last December, but people from all over the country still convene on forums and in Facebook groups to argue about who killed her and why. Private investigators seeking the now $54,000 reward for information leading to Jessica’s killer have trawled the county for clues, but the dozens of diehards who post every few hours about Jessica’s case have never even been to the scene of the crime: Courtland, Mississippi, population 512.

These people — who range from C-list conservative bloggers to gluten-free bakers from Montreal, boat enthusiasts from Florida, and grocery-coupon collectors from North Carolina — claim to want #JusticeForJessica above all. Instead, they’ve terrorized her formerly sleepy hometown with their relentless demands for answers to their specious theories. In the process, they’ve spread rumors that have filtered into real life, igniting racial tensions, digging up old skeletons, and reawakening feuds. For these amateur detectives, Jessica’s death isn’t a mother's tragedy. It’s a pastime.

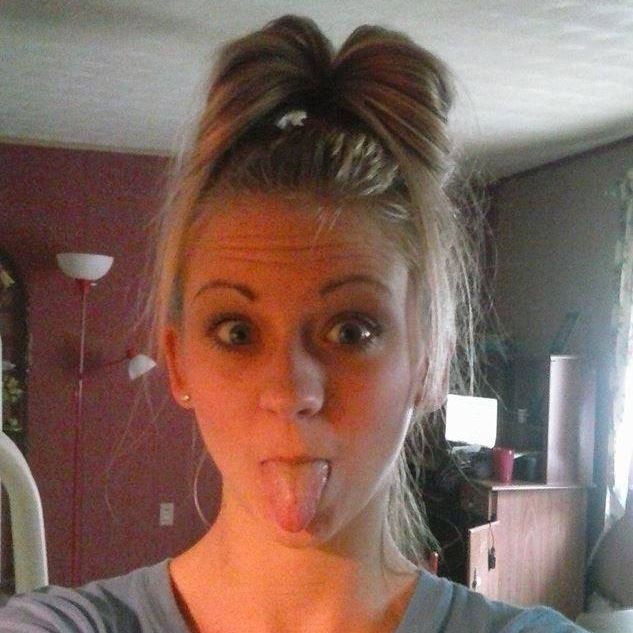

Media critics use the phrase “missing white woman syndrome” to refer to the national obsession with victims who are young, blonde, and white, and Jessica checked all those boxes: The flaxen-haired former cheerleader weighed “90 pounds on a good day,” according to her mother. But the people who are fixated on Jessica’s death are exceptionally invested thanks to her tiny hometown. It’s easy for outsiders to track down social media accounts and even phone numbers for Jessica’s family members, friends, ex-boyfriends, and reputed enemies, all of whom said they’ve been contacted by strangers intent on cross-examining them about whether they killed a teenage girl.

Could you send us a phone log confirming you were where you say you were the night Jessica died? Why does your white truck look like the white truck that a commenter said might belong to the murderer? Care to explain that 2003 drug possession charge? If locals engage with their interrogators, they end up arguing all day with people they’ve never met. They can’t avoid suspicion by staying offline, either, because when they do so, they appear even guiltier.

Before Jessica died, her mother logged onto Facebook only to play Criminal Case, a game in which users work together to solve murder cases by investigating clues and analyzing evidence. Now, Lisa stays up on Facebook until 4 a.m. helping — and defending herself against — strangers who want to binge-watch her daughter’s murder investigation.

Some are generous. More than 152,000 people “like” the “Justice for Jessica” Facebook page run by Jessica’s older half sister, a space for people to share photos and donate books to libraries in her name and pray for her family. They’ve sent Jessica’s family cards and quilts and spa treatment gift certificates and flowers picked from their own gardens. After the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation took Lisa’s laptop for evidence — she says they still haven’t returned it — someone sent her a new one. In May, when Lisa’s phone stopped working, someone quickly mailed her a replacement.

But in return, they demand answers. They want to run their psychic premonitions by Lisa and dissect her parenting skills. When Lisa gets frustrated, they accuse her of being evasive or sending them on a "wild-goose chase.” Sometimes Lisa tries to reason with them. Other times, she fights back. (Recently, after a woman called her “rude,” Lisa wrote back, “You Might understand My BABY was Murdered!! Yes I get angry if you can’t deal with that a little bit i am sorry!!”) Sometimes she tells them what she thinks they want to hear, even if it’s a lie, in hopes that they’ll finally leave her in peace. But Lisa is the first to admit that she doesn’t really want them to go away.

Authorities say they’re working on Jessica’s case full time and are finally making progress, but it’s been months since Lisa has heard any updates, she said, and most of Jessica’s friends don’t stop by that often anymore.

“I don’t want to close the computer, because I don’t want to close my eyes,” Lisa said. “If I close them, I see her burning.”

At around 5 p.m. on Dec. 6, Jessica told her mother she was going out to the gas station and convenience store down the road. She left the house quickly, in camouflage sweatpants with her hair in a bun, and promised she would be back to clean her room before long. When Lisa called her about two hours later, Jessica said she would be home soon. But a little over an hour later, Jessica’s stepmother started pounding on Lisa’s front door in a panic. Her husband, Ben, Jessica’s father, is a mechanic at the Sheriff's Department, so the police had called them first.

“I just didn’t believe it,” Lisa said. “Jessica and I had just gotten off the phone. How could she be on fire?”

Investigators say they’ve been able to track exactly where Jessica was the week before she was burned alive, but not during that final hour. Jessica did go to the gas station after getting a call from a friend — surveillance video captured her pumping gas and waving to someone off camera — but then she made a few more stops, one at an unnamed residence and another in a town five miles away, before she arrived at the scene of the crime, a rural road about a mile away from the gas station, by 7:30. Courtland’s volunteer fire department received a call about a car on fire at 8:09.

They found Jessica down the road from her car. Although more than 90% of her body was burned, she had somehow managed to escape. They flew her to a hospital 60 miles away in Memphis, while she was still conscious. Later, investigators said they believed the killer had been in her car before setting it alight.

“Eric did this to me,” Jessica told medics over and over again in a raspy whisper, although no one knows whom she meant. (Authorities won’t confirm her last words on the record, but that’s what they told her father and a few potential leads.) Then, she stopped talking. She died in the hospital a few hours later.

Courtland and surrounding Panola County, population 34,000, has its share of gang violence and drug activity. Shootings and drug busts happen. But Jessica’s mysterious, gruesome death shocked the whole town. Everyone knows everyone in Courtland — Jessica grew up on the same street her mother grew up on, across the road from her grandmother and a few doors down from her father — and both authorities and locals believe the attack was personal.

By all accounts, Jessica was a normal Courtland teenager, rebellious but not much more so than other kids who live in the area. She was dramatic and feisty, smoked pot, and sometimes hung around with a rough crowd. But Jessica was also a sweetheart: bubbly, loyal, and generous, too, the kind of girl who would give you her last dollar if you needed cheering up.

“It’s the most baffling case I’ve ever worked on,” said District Attorney John Champion, who said he’s worked for the county for 22 years. He’s been on Jessica’s case since December, along with local investigators, the MBI, the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, and the U.S. Marshals Service. They’ve interviewed and in some cases reinterviewed more than 130 people, Champion said, including multiple Erics and Derricks. The FBI put up billboards in three states asking for tips. Despite the $54,000 award for information, which is double the median income for a Panola County household, authorities have yet to arrest even one suspect.

“I bet if you polled a hundred people and asked them to name their greatest fear of dying, burning would be number one,” Champion said. “When you see a case like this, it’s often very, very personal.”

Investigators have searched for ties to other recent burning cases in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama — Jessica was a white girl who dated black boys, and she wouldn’t be the first white woman attacked for an interracial relationship — but they say they haven’t found any connections.

“I can’t tell you how many different hypotheses we’ve kicked around,” Champion said. Typically, law enforcement can quickly come up with homicide suspects with the help of street informants, he said. But while everyone they’ve brought in has cooperated — given statements, been swabbed for DNA, taken polygraph tests — authorities are no closer to making an arrest.

“No one’s talking,” Champion said. He doesn’t count social media chatter as “talking.”

Recent high-profile disasters, like the Boston bombing and the missing Malaysia Airlines flight, have also attracted the bored, the voyeuristic, and the conspiracy-minded. But Jessica Chambers’ murder wasn’t a huge news event, which is why the rabid, consistent interest in her case outside of Panola County bewilders law enforcement. They said they don’t pay it much attention. The Facebook posters like to think they’re under close watch by the FBI, but Champion said the authorities don’t closely monitor the internet communities and haven’t gotten even one helpful tip from them.

“I’m not going to be intimidated by what the public says,” said Panola County Sheriff Dennis Darby. “They don’t understand how the process works. They don’t know that we have top investigators working on this 24/7.” Both Darby and Champion said they’re confident they’ll eventually solve the case, especially with the help of the FBI’s cellular technology. If they could only figure out where Jessica was during her last moments — and whom she was with.

“You know how we’ve got a town of about 500?” Lisa asked. “There are maybe 50 that ain’t suspects.” She was kidding, of course: The authorities have been clear that there are absolutely no official suspects. But for the most part, they haven’t corrected the misinformation floating online in hopes that will make it easier to find the real perpetrator. For example, it’s widely believed — mistakenly — that the murderer poured lighter fluid down Jessica’s throat, Darby said. But it’s also widely — and mistakenly — believed that some of the people closest to Jessica had something to do with her murder.

The lack of official suspects hasn’t stopped one baseless rumor after another from circulating on the internet and then throughout the town. Some popular theories among internet obsessives and locals involve Bryan Rudd, Jessica’s ex-boyfriend from high school, who some speculate murdered Jessica in a crime of passion because she wouldn’t take him back. Jessica had left him for his friend, who went to jail last fall — who’s to say her new boyfriend didn’t order a hit on her? Others say Jessica sold someone a few hundred dollars’ worth of bad pills, a risky decision that could have made a drug dealer angry. Some have pointed fingers at Charlotte Wilkerson, Jessica’s neighbor and closest confidante, who was one of the first people questioned about Jessica’s murder. Another theory on Facebook involves a number of older women who were reportedly jealous of Jessica, and another concerns George “Boone” Mister Jr., who has a long local rap sheet and had said he was questioned by police regarding his involvement in a “lovers' quarrel” with Jessica. Others are suspicious of Ali Fadhel, the 19-year-old gas station clerk who was the last person (known to the public) that saw Jessica before she burned.

Then there’s Ben Chambers, Jessica’s father, who did time for manufacturing crystal meth a decade ago but now works for the county sheriff. The theories about Ben’s involvement may be the most outlandish: Was Jessica killed in retaliation related to his past? Was it revenge for snitching to her dad? Some people have even surmised that Jessica was a wired informant.

Law enforcement officially cleared Ali after he started receiving death threats, and investigators have said publicly that Ben and Bryan were never considered suspects to begin with. Again, authorities have not identified anyone as an official suspect. But since they have yet to make an arrest, the wild speculation continues. People mistakenly fingered as suspects in high-profile cases have won cases and settlements before, but no one I spoke to said they were considering legal action against the bloggers or internet commenters who’ve ruined their reputations and Google search results.

Sheriff Darby said he ignores the calls he gets from people all over the country, which he called “nonsense.” But other Courtland residents feel compelled to clear their own names — even if that means they have to share something bad they’ve heard about someone else.

The stranger who wrote to Theresa Fleming, Bryan Rudd’s mother, had a simple question: Was Bryan in Courtland the night Jessica died? Bryan says he wasn’t — he’s lived in Iowa since 2013 — but he’s still considered a suspect online and around town (although not by authorities). Jessica was his first love, and he took it hard when she broke things off. In fact, it’s the reason he left Courtland.

In the weeks after Jessica died, conservative blogs and offshoots of the internet vigilante collective Anonymous complained that the mainstream media wasn’t covering Jessica’s murder because of “reverse racism.” They fingered Bryan as the main culprit, mostly based on old Facebook photos of teenage Bryan flashing what they said were gang signs. One photo was captioned “Squad Up.” Ask any teen, and they’ll tell you “squad” is slang for a crew of friends. To the internet, it was evidence that Bryan belonged to an “active criminal gang in the area” called the “Black Out Squad.” Blog posts like “Jessica Chambers Burned To Death By Former Boyfriend?” popped up daily. No one took notice of the question mark.

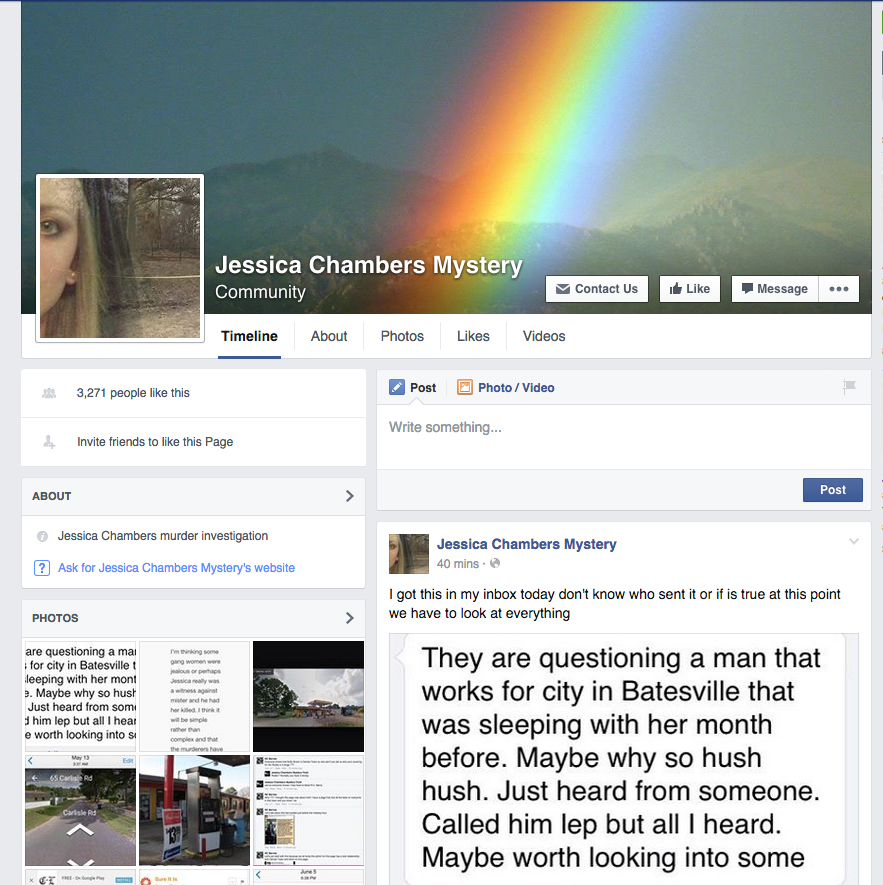

Theresa tries not to read what people are still saying online about Bryan. But every so often, she feels compelled to clear some rumors up. Recently, she politely answered questions and debated members on the “Jessica Chambers Mystery” Facebook page, which has more than 3,000 likes. Offline, she was less understanding.

“Bryan can’t take this anymore,” she said. She didn’t always like what Bryan posted on Facebook either, she said. But he was just messing around with his friends. An 18-year-old named Lex told me their friends nicknamed themselves “The Black Out Squad” when they were barely teenagers — the Facebook group they created with the same name hasn’t seen much action since 2011. They weren’t in a gang, Theresa said, and Bryan wasn’t plotting a murder.

“This has nothing to do with him,” she said. “These are all miserable people who have nothing else to do and are just sitting online, twisting his words.”

Theresa wanted Bryan to talk to me, but he said he’d had enough. At first, she said, Bryan was happy to help find Jessica’s killer, which is why he spoke on the phone with the nice man who seemed like he really wanted #JusticeForJessica soon after her death. That man turned out to be Got News’ infamous Charles C. Johnson, who was recently banned from Twitter for remarks made about Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson. Johnson actually defended Bryan — he said he wasn’t really a gang member and that white supremacist gangs were likely to blame for Jessica’s death instead — but posted a recording of their phone call online without his consent, Theresa said. Months later, Bryan is still fielding messages and calls. They’ll tell Bryan they know he didn’t kill Jessica to win him over, then press him for more details before turning on him later, Theresa said.

Bryan wasn’t the only black person from Panola County who was immediately deemed suspicious online, if not definitively guilty. Panola County is 49.4% white and 48.6% black, and both black and white locals told me that racial tension had never been a big problem. By and large, Panola County is just like most places in America, where declarations of racial harmony coexist with unacknowledged prejudice: Lisa told me she had good relationships with black members of the community a few hours before she called some black people by the side of the road “n*****s.”

But it wasn’t locals who turned Jessica’s murder into a race issue. It was online obsessives who decided that Jessica had been part of a gang and that the black community had retaliated against her for trying to turn her life around. Internet sleuths grasped at everything they could to support this theory, from vicious but unrelated Facebook statuses about police brutality to evidence that Jessica hung out where black people hung out. The rumors filtered into real life: Her former co-workers said they heard that black people weren’t allowed to come to Jessica’s wake. The narrative still carries on. In June, a Facebook commenter wondered if the media was “given orders to put the kibosh on an investigation of a black on white crime because it doesn't fit the national narrative.”

“The tension is just getting worse, and worse, and worse,” Theresa said. “White people act like they’re afraid of these little black boys now.”

Even Jessica’s mother said Jessica often told people flat-out that her mother was racist. Lisa denied the accusation and said it wasn’t about skin color: She just wanted Jessica to date someone who took good care of her, and she didn’t think that someone was Bryan. Bryan and Lisa never got along, and Theresa thinks that’s why Lisa hasn’t done enough to shut down people who think Bryan was involved in Jessica’s murder. Theresa also thinks that rumor takes the focus off of Lisa’s own parenting.

Lisa “could have knocked those rumors down, but she added fuel to the fire,” Theresa said. “All these people on Facebook don’t know what really went on at Jessica’s home. I don’t know how that girl went through so much and still had such a sweet spirit.”

Jessica grew up in a tumultuous household, like many of her friends, relatives, and neighbors. Her father pleaded guilty to manufacturing crystal meth and was arrested for driving under the influence in the early 2000s. Her 28-year-old neighbor was shot multiple times in his front yard in 2006. Her older brother died in a car accident in 2012. As a result, Jessica was tough. If her mother screamed at her, she’d scream back and move out for a few months. According to multiple people who said they witnessed Jessica fighting, when her siblings or friends or boyfriends hit her, she’d fight back just as hard.

Jessica was also manipulative, unafraid to lie or steal to get her way. “She would tell stories big time to get what she wanted,” Lisa said. For example, she said, Jessica would tell people her mother locked up all her food so they would give her money to go to Burger King, or that her boyfriends had to bring her mother cigarettes, which Jessica would later smoke herself, if they wanted to pick Jessica up. But although Lisa and Jessica fought, they loved each other just as fiercely.

“I know I might not act like I love you but I really do!” Jessica wrote to her mom one Mother’s Day. “Thanks for being there for me when nobody else was.”

Lisa said Bryan was a controlling and aggressive boyfriend, but his mother, Theresa, said it was the opposite: Bryan was there for Jessica when her family wasn’t. In winter 2013, Jessica moved out of Lisa’s house and lived with Theresa and Bryan for a few months. At first, Theresa told Bryan that Jessica couldn’t stay. Then, she said, she heard Lisa yelling at her on speakerphone. “There’s no way you’re coming back to my house if you’re with that n****r,” she said they said. (Lisa said she had “probably” said that but that she “didn’t call him that word as being racist.”) One morning, Theresa saw Jessica and Bryan sleeping together on the front porch, shivering in the cold. So she took Jessica in, and grew to love her like a daughter.

In May 2013, Jessica was living with her mother again. She was seeing someone new, but was still talking to Bryan. One day, while the two were alone in her mother’s house, a gunshot went off. Jessica said Bryan tried to shoot her because she wouldn’t get back together with him. Bryan said Jessica tried to shoot him in order to get him out of the house. The only charges related to the unresolved shooting were filed by Lisa, who pressed charges for trespassing (Bryan pleaded not guilty) and for petty theft because Bryan took the gun with him (Bryan pleaded guilty). After that, Theresa sent Bryan to live with his older brother in Iowa.

By the time her newest boyfriend went to jail last fall for robbery, Jessica had been in the process of getting her life together for a few months. She spent a few weeks at a Christian shelter that helps women “become productive citizens” after she accidentally hit her grandmother, her mother said. She got a job at Goody’s department store, where her co-workers doted on her, taking her on trips to Halloween haunted houses and saving her on-sale clothes from the juniors section that only Jessica could fit into because she was so tiny. Her dad gave her back her car, which he had taken away until she stopped hanging out with friends he disapproved of.

Both Lisa and Ben said Jessica made comments that people thought she was “snitching” to the police in the weeks before she died. Afterward, gang members offered their condolences, her parents said. Lisa said some of them knocked on her door in the middle of the night in the weeks after Jessica died to ask whether the “snitching” rumors were true. They seemed to know as little as Lisa did.

“I think Jessica got in over her head with some people and found out some things she shouldn’t have known, because she was smart off her own mouth,” Ben said. Both her parents said they wish they had tried harder to find out who thought she was snitching, or what she was snitching about. But they didn’t. Because Jessica was just being Jessica, and it wasn’t unusual for Jessica to be in some sort of fight or another, drama being one of few activities to pass the time in Courtland.

“I wish that people would know that Jessica, regardless of whatever mistakes she made, was a good person,” Theresa said. “She did things that every other teenager does. But she’s not here to defend herself.”

While “snitching” can get you killed in Courtland, the town thrives on backhanded gossip. At one time or another, most people have been involved in situations they’d rather not recall: drug busts, assault charges, or even plain old relationship woes. Just because someone committed a crime, attacked their sister, or cheated on their husband doesn’t mean they killed Jessica. But internet speculation about the murder has pressured panicked locals into deflecting suspicion by outing each other’s dirty secrets.

And at the right moment — on a tree-shaded country road with the rush of 13-year-old cicadas pounding in your ears, reading a particularly astute-seeming Facebook comment — any theory, however ludicrous, can sound plausible.

The stranger who wrote to Jessica’s beloved neighbor Charlotte Wilkerson had simple questions: Why did Charlotte claim there was a party on the night Jessica died that no one else had heard about? And why did police keep Charlotte overnight after they took her in for questioning two days after Jessica died? This is a big point of contention on the internet, where many people think Charlotte is the key to solving Jessica’s murder.

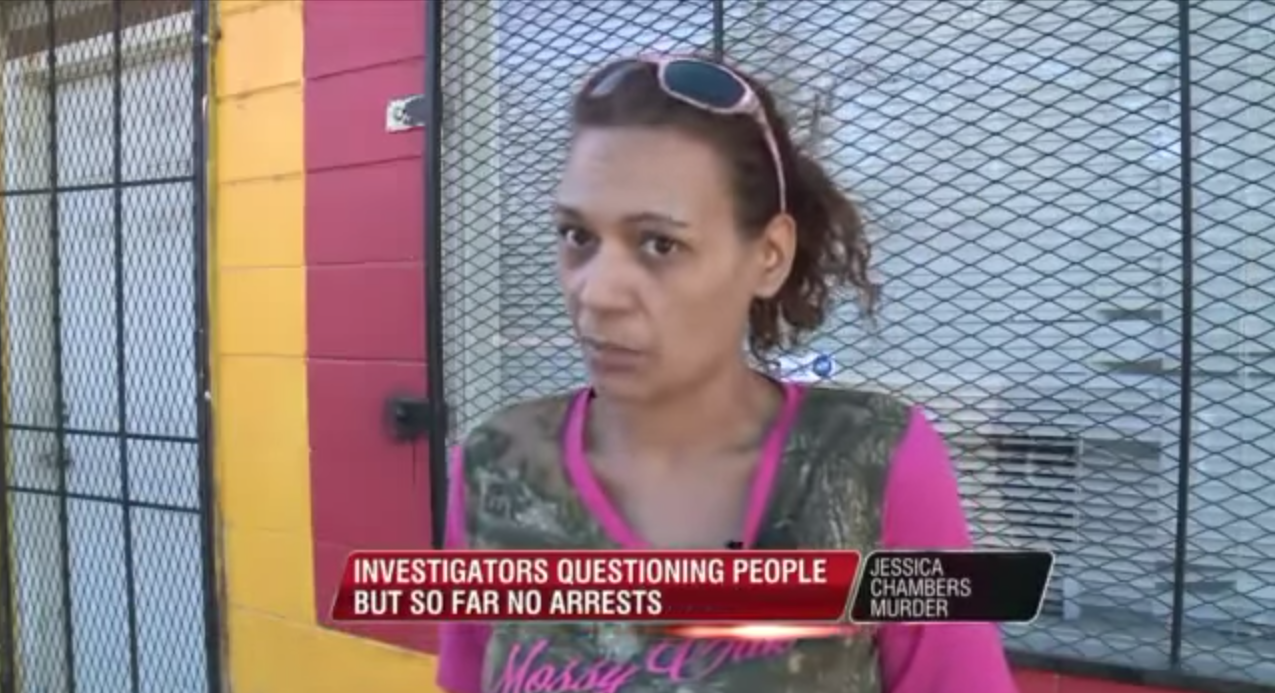

“There was a party going on, and she was there, when she left the party, that’s when it happened to her.” That’s what Charlotte told reporters shortly after Jessica was killed. She also said she was brought in for questioning because her phone number showed up as one of Jessica’s most frequent contacts.

Jessica’s parents didn’t know what their daughter had been up to or whom she had been hanging out with before she died. When Charlotte said she did, it mistakenly gave commenters the impression that Charlotte knew more than she was letting on, leading them to pick apart her 15-second-long interview clip as if they were forensic analysts.

“How can Charlotte Wilkerson be so absolutely certain of the facts around the mystery party?” one wrote.

“This just really don't set right with me,” said another. “Even in the video, she was uncomfortable when she said this, it's obvious.”

Charlotte lives across the street from Lisa, but the two rarely speak. Theresa shares Lisa’s distrust of Charlotte: It’s one of the few points they agree on. (Not that they would know, because they don’t speak either.) But in person, on her front porch while her mother and two young children stood shyly nearby, Charlotte was eager to talk about the girl who called her “Auntie Sha-Sha” because they were as close as blood relatives. She’s not trying to hide anything, Charlotte said. She just doesn’t understand why she should go on the internet to defend herself against ridiculous rumors to people she’s never met.

“I’m not the coolest of heads, and I don’t want to snap and have the lynch mob after me,” she said. “I don’t need the drama. If you really think I’m that bad, come tell me.”

Charlotte said she first got to know Jessica after she yelled at her to get out of the road — Jessica, an accomplished cheerleader, liked to do cartwheels up and down the block while cars sped around the stop sign–less corner. “Don’t tell me what to do,” Jessica yelled back. Charlotte apologized, and the two eventually grew close. Jessica would go to Charlotte’s whenever she wasn’t getting along with her mom. She’d help Charlotte cook or sit with her kids while they did their homework, Charlotte said. Mostly, they just kept each other company.

“She’s so tiny and little, I just wanted to keep her like she was mine,” Charlotte said. “When I don’t see her blonde hair bobbing in my driveway, it really kills me. I keep expecting to see it. But I know I won’t.”

Jessica was supposed to go to Charlotte’s son’s birthday party the night she died, Charlotte said. When she didn’t show, Charlotte figured she had gone to a party she heard was happening down the road, which is what she told reporters: It was the only helpful information she had. Then and now, Charlotte had nothing to hide, so she told them everything she knew, she said. Her problem is that she really has no idea what happened to Jessica. All she has, like everyone else, is her own theories.

Jessica had recently been going out more since her boyfriend went to jail. Had she gotten into trouble that way? “I think it was a setup from the get-go,” Charlotte said. “She was a cute little blonde girl, and I hate to say it, but some bitches are jealous.”

“I think about it over and over,” Charlotte said. “It sounds to me like a crime of passion. Someone had to have a strong vendetta against her.“

Charlotte admitted that she had been questioned a few times, but said the police always let her go. “If they really thought I was involved, I’d still be there,” she said, “but I can’t defend myself for something I don’t know about.”

It’s terrifying, Charlotte said, but the worst part is that she has no way to help.

“If they think you have something you’re not telling them, they’ll lock you up,” she said. “I wish to God I knew something that I could tell these people. I wish I could help them find her, find what happened to her, and find her true murderer, killer, whatever idiot that did this to her."

The investigation into Jessica's murder has exposed high levels of drug-connected gang activity, Darby said in April. Many of the people brought in for questioning have reason to lie, even if they don’t know who killed her. Charlotte herself has been repeatedly questioned about her alleged drug habits and connections, she said.

George “Boone” Mister — who was questioned regarding his involvement in a "lovers' quarrel" with Jessica — also said he keeps getting hassled by the police.

“Everywhere I go, they pull me over, they take me to jail on all kinds of bogus stuff,” he said — they even question his girlfriends to ask whether he ever talks in his sleep. “I took a lie detector test, they swabbed my mouth, they asked me a million questions, and I passed it all,” he said. “Goddamn, what else they want?”

When the police aren’t bothering Boone, Facebook users are: Boone has also written angry posts in groups and responded to personal messages, where he insists he has nothing to do with Jessica’s murder.

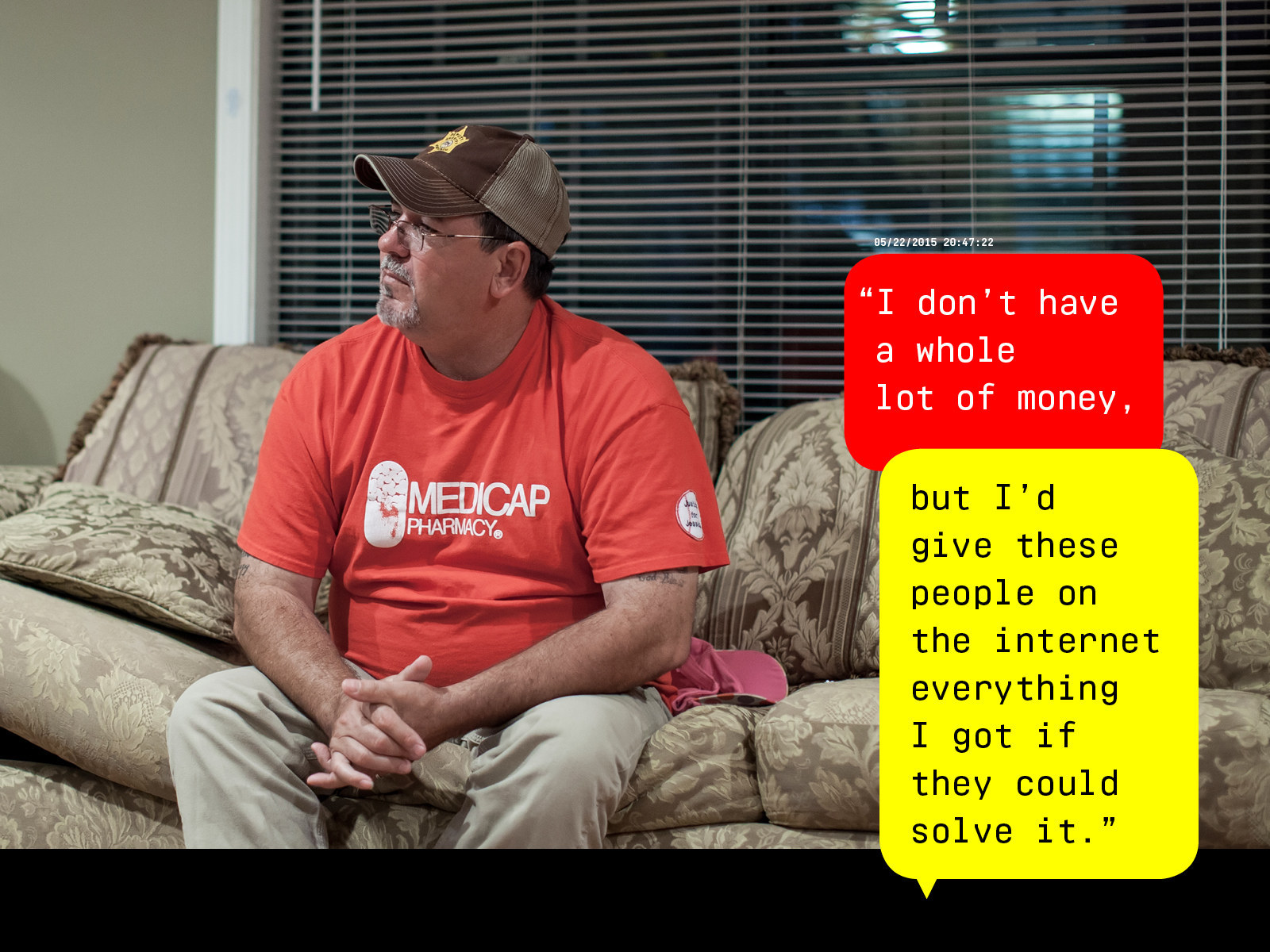

Jessica’s father, Ben, said it’s been painful beyond belief to be accused of murdering his own daughter based on his past mistakes. The rumors that Jessica’s murder is tied to the death of his son in a car crash just three years ago, in May 2012, are even more upsetting. Authorities have repeatedly said Ben is not, and has never been, a suspect. But Ben, who said he owes $10,000 in funeral expenses, recently hired an attorney because he can’t collect insurance from Jessica’s death — it’s because the murder is still unsolved, investigators said.

Ben tries not to think about the investigation too hard, even though he works at the sheriff's compound where his daughter’s blackened car was impounded. He knows the investigators are working as fast as they can, he said, and they don’t tell him much.

“If I knew anything, I wouldn’t be sitting here right now,” he said from his living room couch. He had just come home from his youngest daughter’s softball game. She’s the spitting image of Jessica — just as blonde, skinny, and sassy — and Ben wants to move her away from Courtland as soon as possible.

A Jessica Chambers memorial quilt, made of hot pink and zebra-print patches along with Jessica’s photo, and birth and death dates, hangs on the wall. The words “THE SECRET GROUP” were stamped on the upper-left square. Ben doesn’t know what the phrase means, just that the quilt came, as did the other gifts he’s received from around the world, from a stranger on the internet.

Ben doesn’t bother to defend himself online. If uncovering skeletons leads to Jessica’s murder — even if they are his own — he thinks it’s for the best, he said.

“Jessica was really just trying to find herself in the world,” he said. “I don’t have a whole lot of money, but I’d give these people on the internet everything I got if they could solve it.”

“Who is this?” Lynnsey Fowler, one of Jessica’s sister’s friends, asked the stranger who Facebook-messaged her in late May.

The woman, who called herself “Marie Harmony,” wrote that she wanted Lynnsey to know that there was a detailed eight-page letter floating around the internet that implicated Lynnsey in Jessica’s murder.

Marie thought the letter was “hogwash,” she assured Lynnsey, but she wouldn’t tell her who sent it to her, just that it had also been sent to the FBI. She was willing to tell Lynnsey what it said, but only if Lynnsey promised not to rat her out. If Lynnsey did, Marie would be kicked out of an exclusive private Jessica Chambers discussion Facebook group, where contacting suspects was not allowed.

At first, Lynnsey didn’t know or care what Marie was talking about — she was upset about Jessica’s murder, of course, but hadn’t been close with her in years. But as Marie relayed a complicated plot involving Lynnsey’s husband, relatives, and neighbors that cited Lynnsey’s old Facebook statuses as “evidence,” she got angrier and angrier, especially when Marie brought up an emotional post Lynnsey wrote last November about overcoming an addiction to pills.

“I do have an addiction,” Lynnsey told me. “I’ve fought with my addiction for a long time. It makes me sick to my stomach that these people would take part of my life, like a puzzle piece, and try to fit it into Jessica Chambers’ murder.”

Marie claimed to be on Lynnsey’s side, and maybe she was. But on the same day they talked, Marie also sent Lisa the letter as well as posted about it in a private group. It’s a strategy many Courtland residents are familiar with by now. A stranger calls or messages them and elicits information by claiming to want to help clear their name. They’re pressured into answering more and more questions, often about dark times in their past that have no connection to Jessica’s murder, because their silence would imply guilt. Later, their responses are often screencapped and posted online, or used as trump cards in arguments.

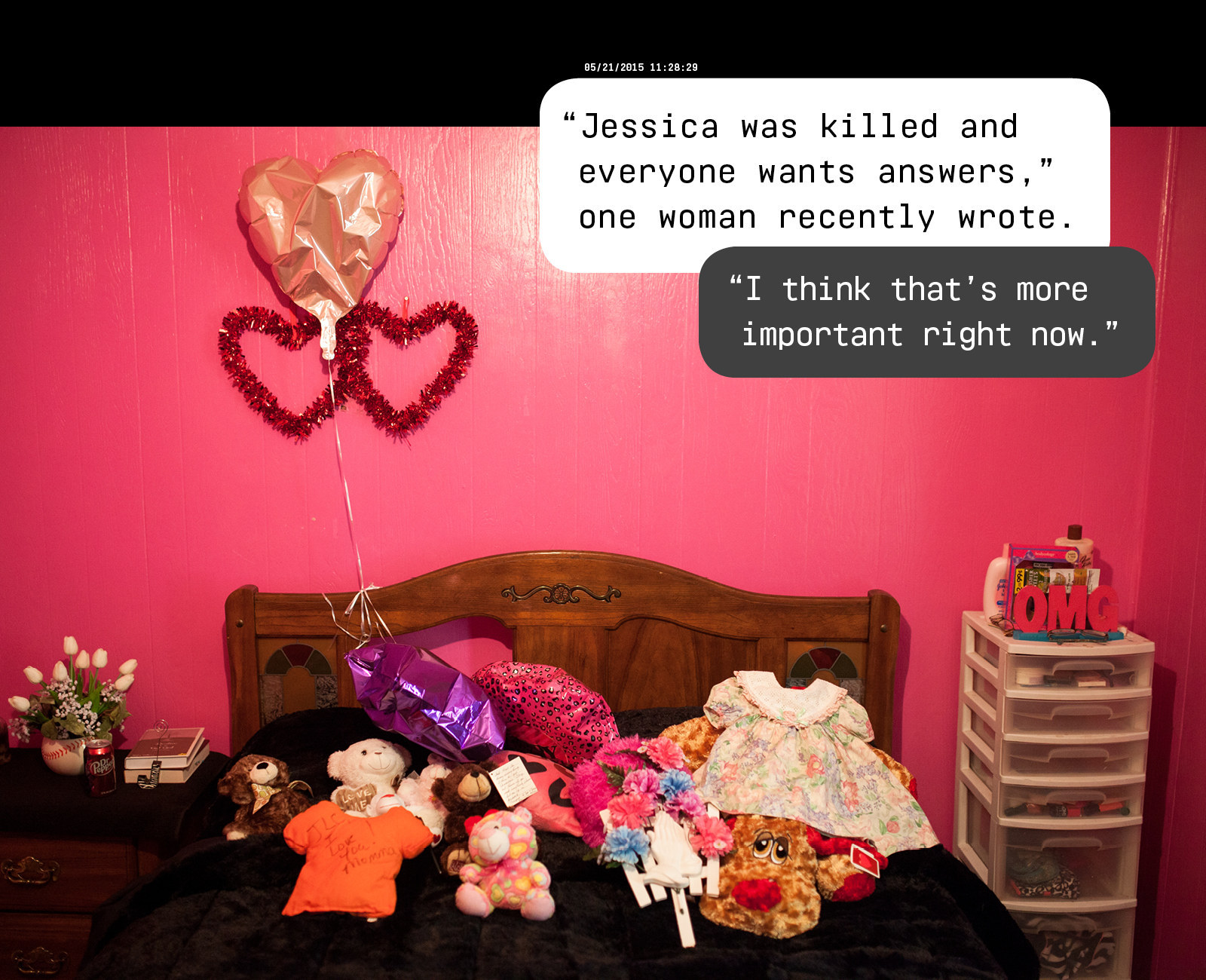

If anyone protests, they're reminded that there’s a murder to solve. “Jessica was killed and everyone wants answers,” one woman recently wrote. “I think that’s more important right now.”

Marie wouldn’t disclose her real name to me, just like most of the diehards, even though they spend their months and weeks and hours tracking down other people’s full names and family trees and arrest records. But she said Lisa had asked her to stay involved, or else she “probably would have walked away a long time ago.”

“It’s not about me,” the person who runs the Facebook group called Jessica Chambers Mystery said when I asked who they really were. My request to join one of the most active private groups was declined due to concerns about my own identity. “It's been crazy with all the suspects online and trying to keep them from knowing what we are talking about in there,” explained the group’s leader, “RC” Barnes.

Barnes is one of the Facebook sleuths most committed to Jessica’s case. He is also one of the most contentious. One user wrote in May that Barnes had accused “everyone from ISIS to anyone in the state of Mississippi who happened to be African American” of being involved in Jessica’s murder. Barnes told me that he didn’t like it when people claimed Ali Fadhel and Bryan Rudd were “normal kids” instead of “the gang members that they are.” One of Jessica’s family friends, Heather Parker, said she wanted to file a restraining order against Barnes because he wouldn’t stop falsely accusing her of profiting off a few hundred “Justice for Jessica” T-shirts. (Barnes said he still thinks she did.)

Barnes, who said he is 40, has never been to Courtland. He lives on a boat and spends his free time on his phone investigating small-town corruption, which he typically hears about through Anonymous.

“There’s no TV or nothing on my boat, so I get on the internet,” Barnes said.

He said he believes that the FBI is collecting the information he posts online, but hasn’t reached out directly because he knows “for a fact” that anything he says on Facebook or Twitter is tracked.

As far as those who say he’s overstepped his boundaries?

“I think that’s bullshit,” he said. “It’s freedom of information; everybody should be able to have the knowledge of what happened. That’s one of the things that I do. That’s why I got involved with it.”

Ostensibly, this is all for Jessica, which is why the thirst for knowledge (and theatrics) disguised as truth-seeking trumps personal feelings. But their behavior implies otherwise: the infighting, the use of “suspect testimony” (screenshots of Facebook chats) as trump cards, the reiterating that the theories they put out in the world and past skeletons they expose are just their own opinions.

“What did I ever do to you?” they whine if Lisa doesn’t respond to them. “Everyone in Justice for Jessica picks on me,” another complained. One woman recently thought so hard about possible theories that her “anxiety shot through the roof so bad I’ve had to take my anxiety pill trying to calm down,” she told Lisa.

In Courtland, residents don’t have time to be so neurotic. They’re too busy trying get back to normal after Jessica’s death — and deal with its lasting damage.

Mohamed Fadhel, the 54-year-old owner of M&M 1st Stop convenience store, moved to Courtland from Buffalo, New York, two years ago. He’s never been on Jessica Chambers Mystery or any other Facebook group or forum, he said. But he almost had to close his business after it was reported that it was the last place Jessica was seen alive. He and his teenage son Ali, who sold Jessica gas that night, cooperated with police by turning over CCTV video and answering questions (Ali said Jessica bought $14 worth of gas that night instead of her usual $3 or $4). But because 19-year-old Ali bragged about buying watches and shooting guns on Facebook, where he also posted photos of himself flashing what commenters thought were gang signs in the shop with black men, the internet deduced he had somehow lured Jessica to her death. At the very least, commenters wrote, he must know something. (At the very worst, the teenager, whose father moved to the U.S. from Yemen over 20 years ago, had been instated there by ISIS.)

Ali moved to another county in Mississippi shortly after because of death threats, he said, and his father was barely able to pay his employees or make rent. “Everyone was scared to come here,” he said. “My son is just a kid. Jessica was just a girl. We had nothing to do with this.”

None of the drama, on- or offline, has uncovered Jessica’s killer. On June 17, Karen Dworkin, one of the most fanatical posters in Jessica Chambers Mystery, suggested that the police release more information about Jessica’s final hour, given that they haven’t been able to solve the murder themselves. It was one of more than a dozen comments Karen posted that day on various topics, including whether Jessica had been pregnant at the time of her death.

“Haven't you noticed your dumb remarks get you NO where and furthermore My Jessica's final hour isn't your business,” Lisa wrote back.

She and Karen, a raw food aficionado whom she’s never met — Karen said she splits her time between Montreal and New York — have sparred on Facebook for months.

“They will release whatever they can when they can,” Lisa wrote, “and FYI I Pray they don't show crime scene photos I personally think that is disgusting for anyone to even suggest that they do... Are you people for real?”

But a few hours before, Lisa had reassured the group’s members that she didn’t want any of them to leave, encouraging “wannabe detectives, concerned citizens, or just whoever is willing to look, search, research” to keep on searching for clues.

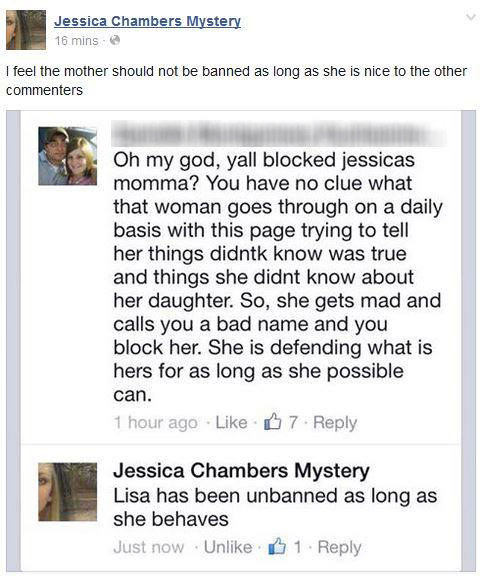

This week, an anonymous user started a new Facebook page called “Jessica Chambers Mystery-Truth” for the purpose of weeding out the drama and false accusations on Jessica Chambers Mystery. A worthy goal, but so far, the posts on the new group concern the same Courtland locals and the same drama (the moderator wrote that RC Barnes “will not be allowed to “spew his tongue”).

Lisa was also briefly banned from Jessica Chambers Mystery, then let back in “as long as she behaves,” according to the group moderator. What will happen if they kick her out forever? How long until Lisa’s supporters and antagonists abandon her and move on to the next small-town tragedy?

For now, they’re still around — unlike Jessica, whom Lisa continued to text after she died, even though she knows how foolish that sounds.

“I know this is crazy but momma needs to talk to you and this is the only way I know how,” she wrote to Jessica the day after she burned to death. “Please text me and tell me I’m dreaming my worst nightmare.”

This story has been updated to clarify a quote from Charlotte Wilkerson.