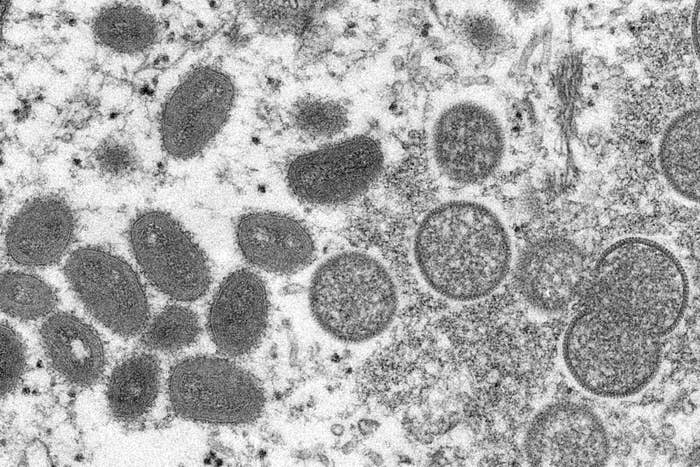

Within the last few weeks, you’ve probably heard that cases of monkeypox — a rare but serious disease caused by the monkeypox virus — have occurred in the US and other countries that don’t normally see cases in nontravelers.

The news has saturated TV and digital outlets, as well as social media, where it’s clear some people are either too exhausted to care or concerned about the possibility of another lockdown, or worse, pandemic.

But before the anxiety kicks in, you should know: There is an effective FDA-approved vaccine for monkeypox that, yes, still works and can be administered after exposure to the virus.

Monkeypox is endemic to Central and West Africa, meaning the virus naturally circulates in animals such as rodents and occasionally causes human outbreaks there. Cases have occurred in countries outside those regions, but usually only in people who’ve traveled to a place where it’s endemic.

The US joins several other countries, including Australia, Portugal, Spain, and the UK, that have confirmed monkeypox infections.

Nine cases have been confirmed in the US across seven states as of May 26: Massachusetts, Florida, New York, Utah, Washington, California, and Virginia. Some of the infections are travel-related, but others are not, which means the virus is spreading locally in some regions, according to a CDC briefing on Thursday.

All of the cases in the US are "within gay [and] bisexual men, and other men who have sex with men," CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said, however there is no evidence this population faces greater risks of infection compared to others. The same trend is occurring in other countries.

The global spread of monkeypox is “highly unusual,” said Dr. David Weber, medical director of the University of North Carolina Hospitals’ Departments of Hospital Epidemiology. This seems to be the first time there’s been person-to-person transmission in several countries outside of Africa. “It’s really hard to judge, but yes, I would expect more cases to emerge,” Weber said, mostly because it can take anywhere from a week to about a month for symptoms to appear after exposure.

The illness typically begins with flulike symptoms such as fever, fatigue, muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes, and chills. Then within one to three days, it causes rashes and raised lesions that may first show up on the face before spreading to other body parts. Symptoms can last two to four weeks.

This isn’t the first time monkeypox cases have occurred in the US. In 2003, over 70 Americans contracted the virus after contact with infected pet prairie dogs that were housed with rats and dormice imported from Ghana, according to the World Health Organization. Travelers from Nigeria brought monkeypox to the US again in July and November just last year. One case was reported in Maryland and another in Texas.

If you’re exposed to or infected with the virus, the monkeypox vaccine, which is called Jynneos (or Imvamune or Imvanex), is an effective way to prevent serious disease and death, according to the CDC. (Technically, there are two vaccines that can prevent monkeypox disease — the Jynneos shot, which was approved by the FDA in 2019, and the ACAM2000 vaccine designed to fight the related virus smallpox. However, the Jynneos vaccine is the only shot approved for the prevention of monkeypox.)

In the event more monkeypox cases appear in the US, it’s likely Jynneos would be put to work because it’s associated with fewer adverse reactions compared with ACAM2000 and is safe for immunocompromised people, said Weber, who is also the secretary for the Board of Trustees of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

Monkeypox vaccination strategy may require a different approach

While the trajectory of monkeypox spread in the US remains uncertain, we do know that the virus is unlikely to behave like other more contagious germs, such as the coronavirus.

“Monkeypox is never going to have the explosive spread that the coronavirus had,” Dr. David Freedman, president-elect of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, told BuzzFeed News. It’s a zoonotic disease, so it’s most common that people get sick by coming into contact with infected animals. (People can give the virus to animals too.)

Even though transmission between people can occur via prolonged face-to-face contact with large respiratory droplets, spread mostly involves direct contact with skin lesions, body fluids, or contaminated materials such as bedding.

“You might see clusters of cases in certain areas, especially if people aren't taking precautions and are routinely touching each other in healthcare settings,” Freedman said.

All this means the vaccination strategy to contain monkeypox infections will require a “different approach,” Freedman said.

One effective method to quell monkeypox outbreaks is “ring vaccination,” Freedman said. The strategy was used to wipe out smallpox in the 20th century by sending a SWAT team of sorts to rapidly vaccinate all primary and secondary close contacts of confirmed smallpox patients.

“It’s like putting a ring around the person that’s infected,” Freedman said, adding that this approach would work well to control monkeypox infections because of the virus’s telltale symptoms.

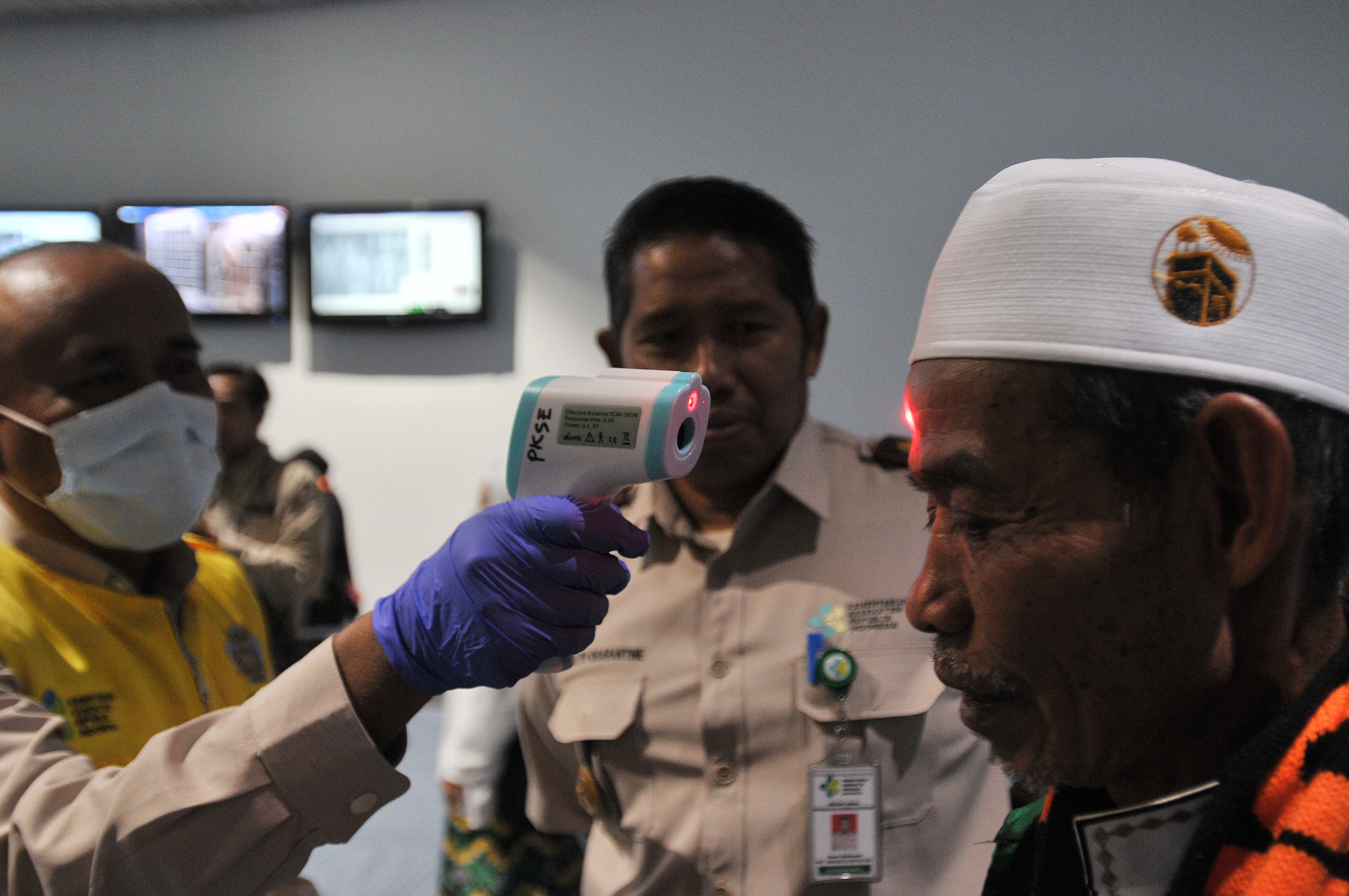

CDC officials said the US is not employing the ring vaccination strategy during a media briefing on Monday, but that it is taking similar actions by vaccinating contacts of confirmed cases if they fall into a high-risk category.

“The good thing about this is that unlike COVID, which can look like a lot of different illnesses and transmit asymptomatically … the only people that transmit monkeypox are those who have lesions,” Freedman said. (The WHO says “the extent to which asymptomatic infection may occur is unknown.”)

“You can isolate them and do a ring vaccination and be fairly certain that only the people they had contact with are suspicious because they wouldn't have been infectious before they develop skin lesions,” he said.

The CDC suggests people who are eligible receive the monkeypox vaccine within four days of exposure to prevent the development of disease, but sooner is better. If someone who was exposed gets the shot between four and 14 days after exposure, they’ll likely still develop the disease but will be protected against severe symptoms.

Monkeypox infections usually subside on their own without treatment, although you can treat the symptoms. There are no medications developed specifically to fight monkeypox virus, but there are three treatments — cidofovir, ST-246, and vaccinia immune globulin — that can be used to treat it in emergency scenarios.

There is an antiviral drug called TPOXX (tecovirimat), which was approved for the treatment of smallpox in 2018, but it's not approved for use in monkeypox patients in the US. (It is in Europe.)

Is the US prepared to vaccinate people against monkeypox if necessary?

The US already has doses of Jynneos in its Strategic National Stockpile, a supply of lifesaving medical supplies and drugs for use in public health emergencies, according to the FDA.

The CDC said the national stockpile has over 1,000 available doses of the Jynneos vaccine, which the US expects will increase over time, and over 100 million doses of the ACAM2000 shot.

Health officials said they plan to maximize the distribution of the vaccine to those they know will benefit from it, including healthcare workers, people with known contact with the virus, and people at high risk for severe disease. The agency said a request to release doses of the Jynneos vaccine from the national stockpile is "actively happening."

Bavarian Nordic, the biotech company that developed Jynneos, said last week that the US purchased $119 million worth of its monkeypox vaccine in freeze-dried form. The first doses of this version of the shot, which have longer shelf lives, will be manufactured and delivered beginning next year.

The announcement was “completely coincidental,” a company spokesperson told BuzzFeed News over email, adding that the purchase was based on a 2017 contract “several years in the making” and not tied to the current monkeypox spread.

But how easily the monkeypox vaccine could be administered in the event more cases appear in the US remains uncertain because the CDC has yet to formally publish its recommendations on who should receive it and when, both Freedman and Weber said.

In November, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend the Jynneos vaccine for people at “occupational risk for orthopoxviruses,” including laboratory employees, those who administer the smallpox vaccine, and people who care for patients infected with orthopoxviruses. The recommendations also say these individuals should receive a booster every two years.

Freedman said the CDC typically doesn’t like to green-light the release of vaccines from the national stockpile unless there are published recommendations from the ACIP.

During the Monday briefing, the CDC said it’s working to develop recommendations to ensure vaccine supplies are available for those who need them.

“It’s a technicality, but that’s the way it is,” Freedman said. The last time the CDC published recommendations for orthopoxviruses was six years ago, when a vaccine wasn’t yet licensed against monkeypox, he said, “so they couldn’t consider a monkeypox indication.”

Weber said the ACIP could theoretically make its recommendations official at any time. But as a physician, he said, he would still need approval from the FDA before writing a prescription for the Jynneos vaccine to treat a patient with monkeypox at this time.

Officials in the UK already said vaccination is being offered to higher-risk contacts of the infected, the WHO said last week.

“I do expect in a short time that we'll start getting some guidance on those issues,” Weber said.

Other important things to know about monkeypox

An important fact to remember amid the chaos is that monkeypox is not a new virus or disease. It was first discovered in 1958 among monkeys used for research, hence its name. The first infection in humans was recorded in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Another is that monkeypox is a DNA virus, not an RNA one, so it’s not related to the virus that causes COVID.

There are two distinct strains of the monkeypox virus. One is the Central African clade, which is generally more severe and transmissible. The second is the West African clade.

Studies from Central Africa where the virus is endemic show about 1% to 10% of infected people die of monkeypox, the CDC says, but more recent case fatality ratios hover at about 3% to 6%. The cases emerging globally now are of the West African Clade, which is known to be less severe and infectious.

Scientists still aren’t sure where monkeypox originated in Africa, but the WHO says rodents are the most likely reservoir.

Because there are so few cases in the US, Weber said there is no immediate reason to modify your daily behaviors to avoid infection. But there are some steps you can take to ensure your and others’ safety.

“If you've had exposure to anyone who you now believe has monkeypox, you should call your health department and do the same things we do for COVID, like wear a mask when you're outside of your bubble and indoors,” Weber said. “And obviously don’t have close contact with people with rashes.”

In countries where monkeypox exists in the animal population, the WHO suggests avoiding poorly cooked meat and being careful when navigating forested areas with potentially infected animals, though this is less of a concern in the US.

Some people in the US may already have some immunity to monkeypox

Both the smallpox and monkeypox vaccines contain the vaccinia virus, a closely related but milder and less dangerous germ. Because all three viruses are in the orthopoxvirus family, a vaccine-stimulated reaction to vaccinia can also protect against the more dangerous viruses.

The Jynneos vaccine contains live vaccinia virus that is nonreplicating, meaning it cannot reproduce in human cells. It also cannot cause smallpox or monkeypox.

It’s administered in two doses given four weeks apart. The most common side effects include pain, swelling, and redness at the injection site, as well as itching, muscle pain, headache, and fatigue.

Jynneos is only licensed for adults and has not been “rigorously studied” in children, according to the CDC. Its effectiveness against monkeypox was determined based on comparisons to the smallpox vaccine and animal studies. Data from Africa show ACAM2000 is “at least” 85% effective against monkeypox.

Children in the US were once routinely given smallpox vaccines, but the practice was discontinued in 1972 when the virus was eradicated. (The last US outbreak was in 1949, and the last naturally occurring case anywhere was in 1977.)

About 3 in 10 people with smallpox died of the virus, and those who survived often lost their vision or were permanently scarred. Currently, only a small stockpile of smallpox virus exists frozen in vials of liquid nitrogen.

If you received a smallpox vaccine as a child, you might have at least a little immunity to the monkeypox virus, according to the CDC, which states that people who have been vaccinated against smallpox should only receive one Jynneos dose if necessary. (The smallpox vaccine often left a shallow, craterlike scar on the back of the arm because the skin was pricked several times to administer the vaccine, which is one way to tell if you’ve been vaccinated.)

If you require long-term protection against smallpox (for example, if you work with related viruses in a laboratory), the CDC says you should get a booster every three years.

UPDATE

This post has been updated to reflect that more confirmed monkeypox cases have been identified in the US.