Nearly 350 children ages 5 years and younger died of opioid poisoning between 2005 and 2018, according to a study published this week, the majority of whom were babies 1 year of age or younger.

Some cases were accidental and occurred following a medical treatment mishap, but others were intentional, meaning caregivers gave children harmful substances, although the exact reasons why are unknown.

The disturbing finding stresses the growing impact America’s opioid epidemic is having on kids, with opioids accounting for 52% of fatal poisonings in 2018 compared with 24% in 2005.

“The study’s findings tell us that children, especially infants, are collateral damage in the current opioid crisis,” said Dr. Toni Gross, chief of the emergency department at the Children's Hospital of New Orleans, who was not involved in the study. “Children 5 years old or younger are unable to care or advocate for themselves, and are suffering fatal consequences from exposure to these substances.”

The research team led by Dr. Christopher Gaw at Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia published their findings in the journal Pediatrics.

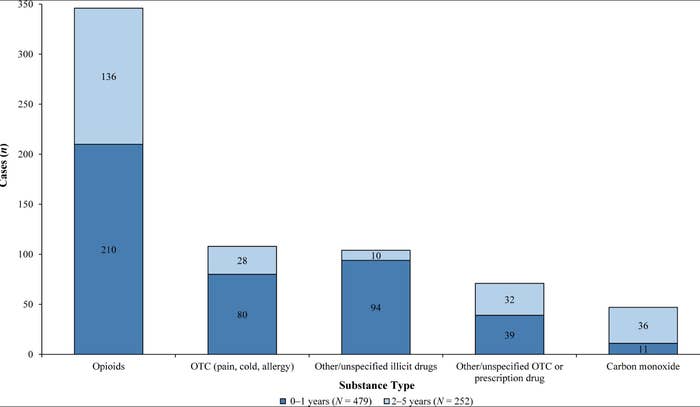

Overall, 731 babies and toddlers overdosed on substances over the 13-year study period, according to child death reviews from 40 states reported to the National Fatality Review Case Reporting System; most fatal poisonings, no matter the substance, involved infants less than 1 year old.

Among the cases where the location was available, 65% of deaths occurred in the child’s home, and about half occurred when a child was supposedly being watched by a caretaker.

Many of the affected children also had an open child protective services case at the time of death or otherwise had a history of previous maltreatment, illness, disability, or sibling placement outside their home. Poverty, substance use disorder, and social inequities were also associated factors in fatal poisonings.

Opioids were the most common substance contributing to fatal poisonings, followed by over-the-counter pain, cold, and allergy medications, other/unspecified illicit and prescription drugs, and carbon monoxide.

Babies less than 1 year old accounted for most cases where amphetamines, cocaine, and alcohol were responsible for fatal poisonings.

Researchers don’t know the reasons behind each fatal poisoning, but among the cases that do have this information available, about 41% of incidents were accidental overdoses and another 41% were due to other causes, such as medical treatment mishaps.

In about 18% of those cases, young children were deliberately given a drug, possibly to sedate them. Overall, 63% of these incidents occurred in kids younger than 2, who are more likely to be victims of intentional or accidental poisonings when given a drug meant for adults because of their dependence on caregivers and “relative susceptibility to toxicity given their size and weight,” the researchers said.

After the Poison Prevention Packaging Act was passed in 1970, unintentional poisonings among children 5 years and younger have “decreased substantially,” according to the study. This law required many medicines and hazardous products to be stored in “special packaging” that would be difficult for a child to open.

In 2008, the FDA recommended that over-the-counter cough and cold medications have child-resistant packaging and labels that not only include age restrictions but also warn parents not to use the drugs, such as Benadryl, to sedate children.

Although these efforts were fruitful initially, poisoning mortality rates over time plateaued, the researchers said, and proved ineffective against deliberate poisonings and those from recreational substances.

In the last decade, however, children have been exposed to new opioid sources, such as heroin, methadone, buprenorphine, and fentanyl, the last of which is considered America’s deadliest drug threat.

Fentanyl is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine. Just 2 milligrams — an amount small enough to fit on the tip of a pencil — can be lethal. And because fentanyl is commonly mixed with other drugs, like heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine, its risks are largely unpredictable — and responsible for huge numbers of accidental overdoses each year.

Opioid-involved overdose deaths in all age groups rose from 21,089 in 2010 to 47,600 in 2017 and remained steady through 2019. This was followed by a big jump in 2020, with 68,630 reported deaths, and skyrocketed again in 2021 with 80,411 reported overdose deaths.

There are changes that can reduce child exposures to opioids and other harmful substances, such as unit dose packaging, which is packaging intended for a single dose. However, the approach doesn’t address all prescription drugs or those bought illegally.

How to prevent fatal poisonings in kids

It can be challenging to prevent poisoning in kids 5 years and younger, experts say, because childcare varies widely among the age group, as do children’s quickly developing cognitive and motor skills.

But the most important thing parents and caregivers can do is to make sure prescription or recreational drugs are safely stored away from kids, said Gross, the emergency medicine doctor from Children's Hospital of New Orleans.

That means keeping drugs in their original containers, out of reach and sight, and behind locked storage boxes or cabinets. (The study found that most fatal poisoning cases in which storage information was available involved substances that were stored in an open area.)

In the event a child does consume a harmful substance, it’s important to look out for symptoms like altered mental status and changes in breathing pattern, such as slower and shallower breaths.

Always call 911 if overdose or poisoning symptoms are suspected.

The time it takes for a child to experience overdose symptoms varies depending on their age and the substance they took. Gross said some drugs are short-acting, meaning symptoms may appear rapidly, and others take longer to affect the body.

Regardless of the particulars, adults should always call the poison control center (1-800-222-1222), which can recommend the next best steps, such as going to the hospital, depending on the details shared.