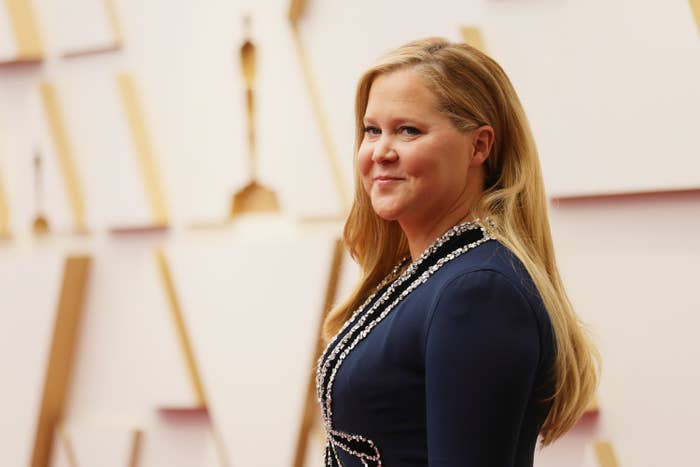

Earlier this year, Amy Schumer revealed a secret that’s been shrouding her personal life in shame since childhood: She has a hair-pulling disorder called trichotillomania.

People with trichotillomania repetitively pluck out hair anywhere on the body, including the scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows. “I think everybody has a big secret and that’s mine,” Schumer told the Hollywood Reporter in February about a month before the release of her Hulu series Life & Beth.

The show portrays her experience with the shame and stigma of trichotillomania as a kid. When she was a teen, she used to eat lunch in the nurse’s office because someone said her bald spots “made them sick,” she told Howard Stern on his radio show in April.

“I would not even realize I did it, and I’d just look down and there was a pile of hair,” she said.

Trichotillomania is part of a cluster of self-grooming actions called body-focused repetitive behaviors that are known for seriously disrupting people’s daily lives and causing significant embarrassment. Skin picking and nail biting are other common examples of BFRBs.

Research suggests that about 1 or 2 in 50 people experience hair pulling in their lifetime, according to the TLC Foundation for Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors, which provides education, support, and information about treatment for people with conditions like trichotillomania. Even so, many people keep their trichotillomania a secret, so the prevalence could be even higher.

“When a person of Amy Schumer's stature has the courage to speak their truth, it helps start to destigmatize and normalize conversations like this about trichotillomania and other associated behaviors,” Jen Monteleone, interim executive director of the TLC Foundation, told BuzzFeed News. “That creates opportunities to build awareness, acceptance, and inclusion, and helps others know that they can live full and productive lives.”

People with trichotillomania often can’t get the help they need because of misconceptions about the disorder — it’s not a mental illness, OCD, or a type of deliberate self-harm — and general lack of awareness among medical providers. More public discussion, advocates say, will help clear confusion and destigmatize the disorder.

Schumer said that while she still struggles with hair pulling, one of her goals for going public was to raise awareness and help millions of people with the condition.

When 21-year-old Rhiannon Sowell’s trichotillomania was diagnosed at the age of 13, she said she “felt crazy” at first. Now, “knowing that a celebrity who is loved and looked up to has it as well just makes me feel less alone.”

People can’t “just stop” pulling their hair out

One of the most common phrases people with trichotillomania hear is, “Why don’t you just stop pulling?” Well, because they can’t. In fact, most people with the disorder will deal with it for the rest of their lives, although people may go through phases where they don’t pull as much or at all.

“If I could quit, I most definitely would’ve done it by now,” Sowell said.

To many outsiders, hair pulling appears to be “a quirky, self-indulgent thing that people engage in for some strange motivational reason,” said Charles Mansueto, a clinical psychologist who researches and treats trichotillomania and other BFRBs. “But it’s a disorder that’s troubling, significant, and ruins lives.”

Hair pulling for some people can be automatic, something they subconsciously do while working at their desk, driving, or watching TV. Others may pluck with more focus, like in front of a mirror with tweezers. For many with the disorder, it’s a combination.

“I could be sitting and enjoying a nice movie with my husband and not even notice my fingers are hurting so bad and all my eyebrow hairs I’ve been growing for weeks are gone,” Samantha Stevenson, 33, told BuzzFeed News. “It’s a lot to go through this, we need more support in the community, not more negative comments that are going to affect us more and make it worse.”

Almost anything can trigger the behavior: certain moods like stress, anxiety, or boredom; different hair textures, colors, or growing patterns; sitting still for too long; and sensations like itching, tingling, or pain at the pull site.

Still, experts don’t know why people with trichotillomania cannot stop themselves from pulling despite desperately not wanting to and fearing what they may look like afterward. In reality, people may pull their hair because it feels satisfying or they want to soothe internal discomfort.

Some evidence suggests trichotillomania could be genetic. Studies show people are more likely to develop the disorder if someone in their family has it, “but we haven’t yet pinned the genetics down with any degree of confidence,” Mansueto said.

Other things could contribute to the development of the disorder, including temperament, age, stress, and environmental factors.

It’s not a form of deliberate self-harm or self-injury

Much of the shame about having trichotillomania is rooted in the fear of what others may think if they know, including the misconception that hair pulling is a type of self-injury like cutting or burning oneself.

In some cases, Mansueto said, “this means professionals are misjudging people with trichotillomania in such a way that may lead patients down the wrong line.”

“I’ve been laughed at for having no eyebrows or bald patches on my head. Even making TikToks, full-grown adults take time out of their day to laugh at my eyebrows (I’m not the best at drawing them on), and it makes me sad that this is what the world has come to,” Stevenson said. “I can’t go outside without fear of being made fun of so I have to put my eyebrows on.”

Schumer’s transparency, however, has helped her find comfort and hope that others will feel less afraid to share their own stories.

“People are so ashamed because it seems to be a self-inflicted disorder that others believe they can just stop if they really wanted to; that’s a level of shame that's very different,” said Mansueto, adding that children with trichotillomania often experience this with their parents who may not know much about the disorder.

Missy Lovell, 26, said she spent years hiding the bald spots on her head just to avoid embarrassing those she loves, including her parents and husband.

“I don't mind being known as the girl who pulls her hair out,” she said, “but gosh, I don't want [my husband] to be the person who’s married to the girl who pulls her hair out.”

Many doctors don’t know how to diagnose or treat trichotillomania

Many people with trichotillomania hide their struggle with the disorder from friends and family, but just as many hide it from their doctors, partly because they feel they won’t know anything about it.

Psychologist Nancy Keuthen, codirector of the Trichotillomania Clinic and Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital, said many medical providers won’t address very noticeable bald patches or missing eyelashes or eyebrows, or what she calls “the elephant in the room.”

That “increases the shame that these people feel and makes them feel more isolated,” she said.

Stevenson’s trichotillomania has never actually been diagnosed by a doctor; she said she had to do her own research and “piece things together” after several failed attempts to address her concerns with medical providers who just told her she had anxiety.

Keuthen and Mansueto both said that trichotillomania is not a type of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a common assumption given people with trichotillomania are often overcome with irresistible urges to pluck and pull. “They’re more like cousins than siblings or identical twins,” Mansueto said. “They seem to be related but in ways that are more distant.”

Trichotillomania is different enough to warrant a separate category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the professional diagnosis guidelines used by all psychiatrists.

Medications used to treat OCD, such as SSRIs, do not help reduce hair-pulling tendencies. However, many people encounter doctors who prescribe them anyway.

Lovell saw about 10 doctors, many of which resorted to prescribing her antidepressants or OCD medications, before finally meeting one who knew all about the disorder and created a plan for treatment.

“It’s very disappointing when people fall into the hands of a professional who means well but believes they understand that trichotillomania is OCD,” Mansueto said. “It could be very discouraging for many people who think they have proper treatment.”

Keuthen said doctors need to know just enough so they can tell patients “there’s a name for this, there's treatment for it, and there's hope that you can learn how to manage this so that it's less distressing and less impactful in your life.”

On a more positive note, Keuthen said the field of trichotillomania and other BFRBs research is “miles different” from what it was decades ago, and that’s promising for those looking for answers.

Cognitive behavioral therapy — an approach that aims to identify thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that contribute to hair pulling and how to change or reduce them — has proved helpful for people in managing the disorder, although the FDA has yet to approve any medication, combination of drugs, or treatments for trichotillomania.

It’s also a common assumption, even among medical professionals, that people with trichotillomania may have experienced trauma. The vast majority of those with the disorder don’t have any more trauma in their life than the general population, Mansueto said, although it may worsen hair pulling in some people.

While traditional talk therapy doesn’t seem to help reduce trichotillomania behaviors, it may help people who’ve experienced trauma, he said.

Schumer’s announcement sheds light on an often misunderstood condition

Several people with the disorder said it was important for the trichotillomania community that a famous actor like Schumer publicly shared her diagnosis. Other celebrities, including Megan Fox, Justin Timberlake, Katy Perry, and Olivia Munn, have mentioned having the condition, but haven’t revealed as much about the personal impact as Schumer.

Her transparency “offers hope and inspiration to others,” Keuthen said. “It reminds them that trichotillomania is not the core of who they are and does not need to define them.”

Schumer actually inspired Lovell to reveal that she had trichotillomania on Facebook — photos and all — something she’d never felt comfortable doing before. She was surprised by the overwhelming love and support she received, including people DM’ing her asking for advice and recommendations.

“I 100% did not expect to come out feeling so confident after sharing a secret I had been hiding since 10 years old,” she said.

“Trichotillomania isn’t embarrassing; it’s human,” Lovell wrote in her Facebook reveal. “... you are NOT alone. You are human. And whatever your mess is, it is beautiful.”

If you or someone you know has trichotillomania, you can visit the TLC Foundation’s website for more information. For help finding a therapist trained in BFRBs, you can search through this directory. Here’s how to find a support group.