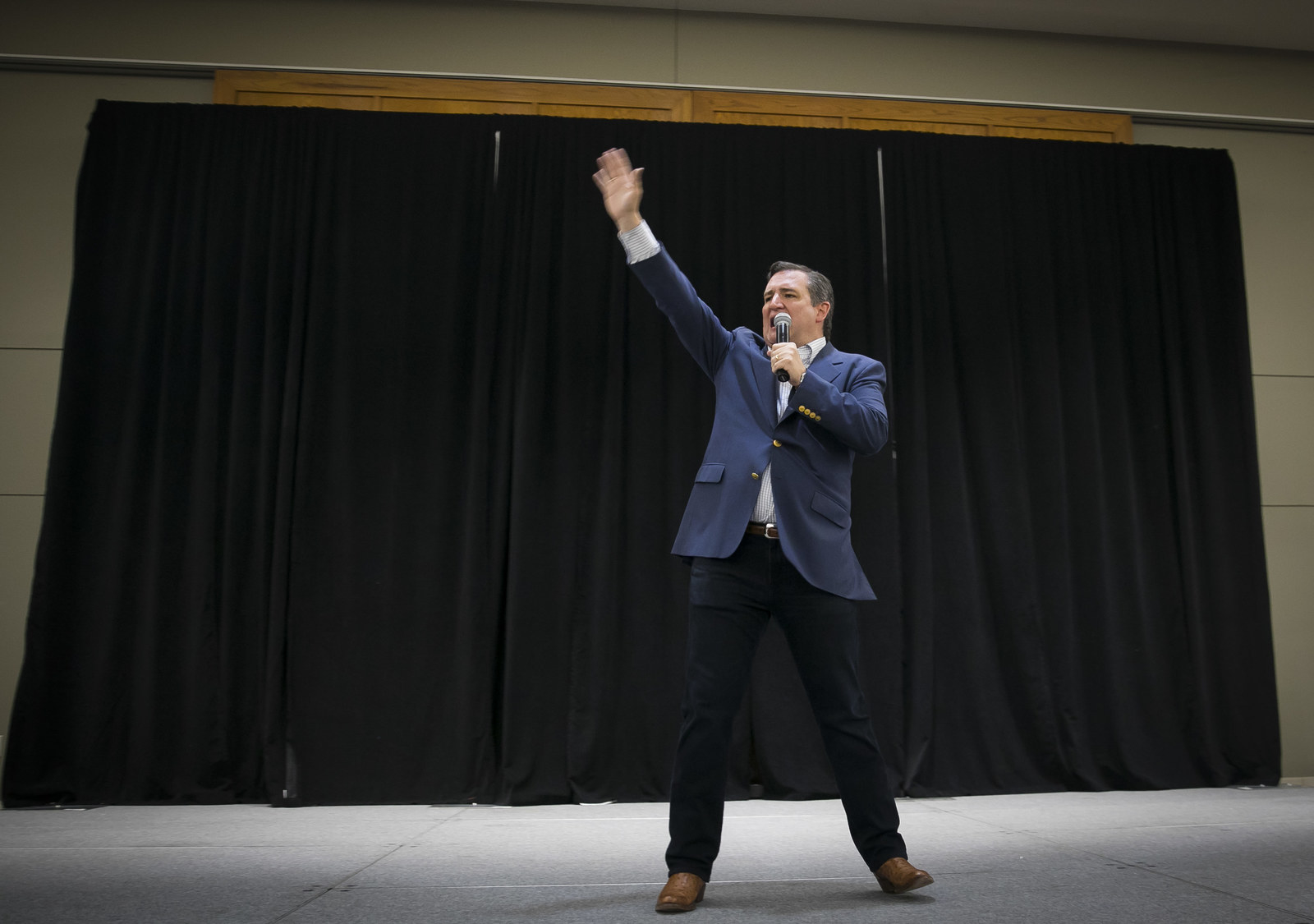

The other night in the San Jacinto Room at the Lone Star Convention & Expo Center (great acoustics!), things were basically normal for a couple hours.

Unlike so much now, what transpired in the San Jacinto Room mostly fell within the realm of what you’d expect from a Republican event: Top 40 country, popcorn and Bud Light, people catching up in the aisle, cheers for conservative judges, Ted Cruz talking about guns and Israel and, overwhelmingly, about the beneficence of low taxes and less regulation, how they’re blessing Texas with good fortune, and how Beto O’Rourke is against both.

This isn’t wrong, exactly, at least not in terms of the gulf between them. O’Rourke does want a bigger government that provides more services, even if it’s more expensive; Cruz wants it leaner and meaner, even if it’s literally meaner sometimes. O’Rourke is really liberal; Cruz is really conservative.

But when it’s laid out like that, there’s that sense of, like, “Oh, right.”

Texas remains a fairly Republican state, and Cruz remains a Republican, and while it’s still possible he could lose, even if he wins by much less than he should, they’ll still call him Senator.

That could be the story in Texas this year, except that it really isn’t, and even on a good, normal night for Cruz, there’s always some other thing lurking around.

In the ol’ San Jacinto Room, the other thing was literally Donald Trump Jr., who’d come to Conroe, Texas, to campaign for the imperiled senator. Right at the top, onstage before a few hundred voters, Trump Jr. told the story of how Cruz and the Trumps came to reconcile after the great bitterness. In Cruz’s usual telling of this story, he flies to New York after the 2016 election and tells Donald Trump about the opportunity before them to bring real conservative policy to America.

This version, however, took place before the election, at “one of those political hoity-toity things,” the annual American Enterprise Institute gala in Washington.

Because he is “the Fifth Avenue Redneck” and most of his friends are from Texas, Trump Jr. was seated right next to Cruz at the Texas table. This could have gone poorly, he feared, given how bad the primary got and — he didn’t mention this — how after Cruz refused to endorse his father at the Republican convention, Trump Jr. had referred to Cruz as “so unlikeable,” “a pure politician” who “only became anti-establishment when he couldn’t get in.”

Now a new cult of personality — the Romance of Beto — is coming for Ted Cruz.

But they had a great dinner. They had a great conversation. And at the end of the dinner, “all those Texas boys said, ‘We’re going back to the Trump to get a couple drinks in the lobby. Ted, do you want to come along?’” He did. “He sat in the lobby with me, my friends, and his, for three hours. He took every selfie that was asked of him.” Trump Jr. would like to believe he would’ve done the same, but as he correctly noted about these things, you really never know until you’ve been in that kind of situation, and few of us will ever be in this particular one. “That says so much of what you need to know about this man, because he realized that he is serving all of you. He realized that he was going to have to work with this president; however rough that could have been, he put that all aside to represent the state of Texas.”

You know what he means — magnanimity in defeat, country and constituent over self, etc. — but it also conjures up the bleak image of a defeated Cruz having to take selfies for three hours at the Trump Hotel.

It’s the parable of the Trump challenger: Cruz would not criticize Trump, for he was sensitive to the cult of personality that surrounded him; Trump then devoured Cruz, devoured all, including the people of principle, and required fealty forever after; and now a new cult of personality — the Romance of Beto — has come for Ted Cruz.

At some point over the last few years, Cruz became a national villain — but in that way where people like to get in a good, satisfying kick where they can. And the Texas Senate race has achieved some higher plane on which all the supply and demand curves intersect so as to continually kick Ted Cruz.

There was the protester at a Resurgent event this summer who kept screaming, “You’re a coward, Ted.” There was that crowd of protesters who chased him and his wife into the kitchen of a DC restaurant, followed by the invariable Twitter jokes about it the next morning, and the attendant video of one protester telling him, “Beto is hotter than you.” Midway through a New York Times chat about the Kavanaugh hearings, columnist Bret Stephens dashed off that Cruz is like “a serpent covered in Vaseline” whose ethics are “purely situational,” a politician “conniving enough to try to put one over you, but not perceptive enough to realize that you see right through him.” Filmmaker Richard Linklater shot a series of attack ads with an old man in a diner talking about all the reasons “everybody hates Ted Cruz,” and who makes Cruz’s own first name sound like an insult, like only a weak-ass person would go by Ted.

“How likable is a candidate? That still counts,” White House budget director Mick Mulvaney told an audience of party officials and donors, in audio that then found its way to the Times. “What do you say to critics like that,” Cruz then heard a few weeks later, “and does likability still count?”

Beto, of course, doesn’t approve of the protesters who scream at Cruz in restaurants or airports. If asked to say something nice, he compliments Cruz on being a good father. Those Linklater ads aren’t really his thing. He’s handsome in the slightly goofy, casual manner generally associated with holding puppies by the scruff of their necks and faded T-shirts that hang the right way and romantic gestures at Christmas, and speaks with the shouted cadence of a teen movie’s impassioned closing speech. He is the object of media affection.

And Cruz isn’t.

He is not entirely unlike Alex Rodriguez (when he was playing) or Anne Hathaway (prior to this year) or Hillary Clinton (for 30 years) in this way: Some segment of the population just doesn’t like him. That sentiment is both thin and slightly inexplicable, but also unshakable.

If you’re in this camp, you usually have a rationale (e.g., Cruz’s position on Obamacare, Clinton’s romance with Wall Street, something Anne Hathaway said six years ago), and depending on the object of your distaste, you may have even heard someone explain The Real Reason you don’t like them (e.g., internalizing years of how a powerful woman is treated). And maybe that’s true — I can’t tally up the full weight of society’s imprint or see into your heart anyway, so only you will know. But when it comes to Cruz or A-Rod or Clinton, is it entirely about the government shutdown or the purity of America’s Pastime or humanitarian intervention’s dark side? Other players juiced; other people voted for the Iraq War; other people have fallen in behind Trump. Something about them just grinds some people’s gears. Maybe it’s the way they talk, the sound of their voices. As George W. Bush is reported to have once told a room of donors, “I just don’t like the guy.”

As George W. Bush is reported to have once told a room of donors, “I just don’t like the guy.”

Even if you’re skeptical of the commonality between Anne Hathaway & co. and Ted Cruz, in the case of each, there is or was a friction between them and what the culture wants. Here’s O’Rourke on a skateboard; here’s Cruz getting blamed on Twitter for the Houston Rockets’ poor shooting from beyond the arc; here’s O’Rourke onstage with Willie Nelson; here’s Mandy Patinkin criticizing Cruz for quoting The Princess Bride. Antonio García Martínez recently observed that “the Right is angry because they have near-total political power, but little cultural power. The Left is angry because they have near-total cultural power, but little political power. Each covets what the other has and feels is rightfully theirs.” Cruz’s career seems a temple built to that dynamic.

“Watch any Republican go on a late-night TV show,” he told the Atlantic this summer. “With a Democrat they laugh, talk about fun topics, they have a great time.” Earlier this year, Cruz — a diehard Simpsons fan — said the Democratic Party is the party of Lisa Simpson, and the Republican Party is that of the rest of the Simpson family; past and present Simpsons staffers dunked on him immediately. The Atlantic recently published a 4,900-word profile of Heidi Cruz that contained an anecdote about his insisting they play a song from Aladdin at their 2001 wedding. Internet publishing practically exists on a foundational economy of adults who love Disney. And yet, a central takeaway from this piece on Twitter and elsewhere was: Check out this weirdo!

There’s an impulse to say, well, Cruz doesn’t care if you don’t like him. “These things don’t bother Ted,” Heidi Cruz said of Trump’s insults, specifically about her appearance. “He’s like, ‘Hah! That was the worst move he’s ever made.’” But they certainly did at one time; in her recent piece on Cruz, Ana Marie Cox quotes from his memoir, in which he describes studying his own unpopularity: “‘Okay, well, what is it that the popular kids do? I will consciously emulate that.’ Cruz eventually discerned that he should brag less about his grades and at least try to play sports.” The faintest suggestion that Cruz might care — that he wouldn’t mind if you appreciated his Monty Python reference — paradoxically seems to inspire more rage from the rest of us. He doesn’t seem exactly like Dick Cheney, who has entered rooms to “The Imperial March” from Star Wars, or Cocaine Mitch McConnell, who seems cold to everything except putting another Federalist Society member on a court.

“How do you prepare for a debate against someone who’s known for his charisma, who’s, you know,” a reporter recently asked Cruz, “popular for that?”

If you think about the above long enough — “Who’s, you know, popular for that?” — if you had to linger over the implication that you were without… Well, what’s he going to do? Like, actually. Not answer the question? Quit the Senate? Go back to litigation? Become one of those forgotten people whose picture you see on a presidential primary Wikipedia page and have to click through to find out who it is?

Maybe you think Cruz deserves this, though. This is your right! And maybe you are right. The ethos of the era is oppositional, to discard the superficial civility that papered over terrible injustice. This year, Cruz has defended Alex Jones’ place on the platforms as a First Amendment issue and attacked Democrats for being “so quick to always blame” the police regarding the case of Botham Jean, a 26-year-old black man who was shot and killed in his own apartment, by an off-duty police officer, for doing nothing but existing. Maybe shouting that Beto O’Rourke is hotter than Ted Cruz to Ted Cruz’s face — a mean but harmless act — is the best one can really do in response to this kind of existential ruthlessness. And maybe, in some weird way, there’s societal utility in being able to pop off about how Hillary Clinton looks like she’s wearing a prison jumpsuit, and unload the difficulties of everyday life onto a public figure who seems distant and impenetrable.

Still, can’t we be cruel sometimes about things that don’t especially matter?

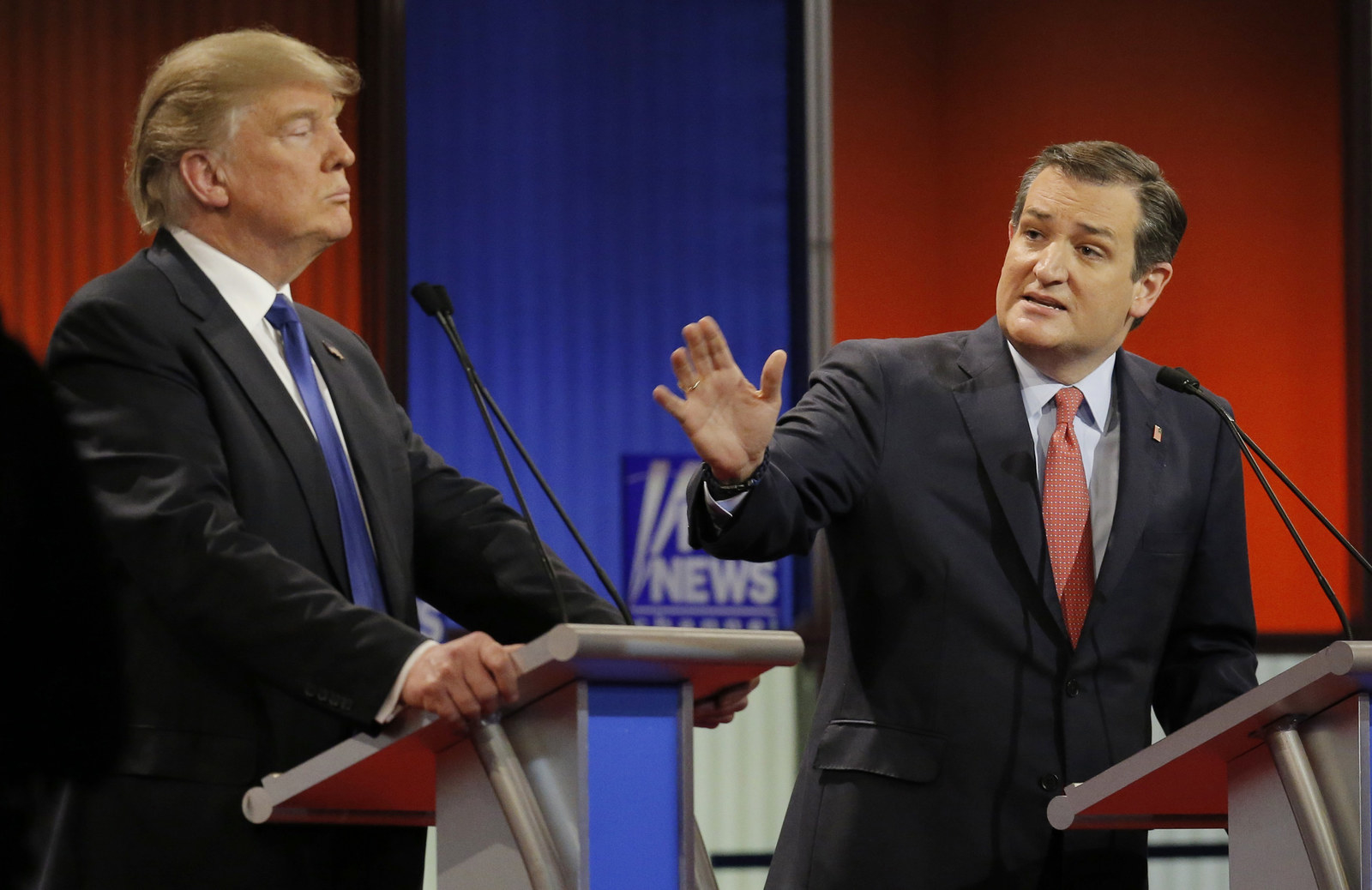

But the Cruz of the last two years is partly the product of the two that came before, and it is worth considering again the baroque weirdness of the 2016 primary, as the Republican Party reshapes in Trump's image.

Cruz ran for president and refused to criticize Trump (“I like Donald Trump. I think he’s terrific. I think he’s brash. I think he speaks the truth.”), a posture he maintained for most of the campaign to an occasionally surrealist art project degree, before he did finally attack Trump’s judgment. When Cruz won the Iowa caucuses, there was a brief, vague sense that now things would return to the expected course — politicians who seemed like politicians would again win — maybe the last time anyone thought that in America.

As promised, Trump crushed him. (“He will fall like all others. Will be easy!”)

In the space of six months, Trump called Cruz a pussy (and in a backhanded way, too, where he asked a woman in the crowd to shout it out, like it was an old college joke that they could finally now share together on television), insulted the looks of his wife, and accused Cruz’s father of helping assassinate JFK.

This, once he actually lost, put Cruz in a position he hasn’t quite escaped.

“If you don’t endorse him, where does that leave you? You don’t have the public and you don’t have the establishment,” Laura Ingraham is reported to have told Cruz at a May 2016 dinner party, to which he invited her. “How can you be a leader of the conservative movement?”

When Cruz chose to not endorse Trump, as prophesied there by Ingraham, he got booed at the convention; the chair of the Washington state party told him he was a “traitor”; Sheldon Adelson wouldn’t let him into his suite; the next morning, Texas delegates shouted at him. (“All he was doing is helping Hillary Clinton. And he’s a liar.”) By this point, people who were once cool to Trump had mostly lined up behind him, where they remain.

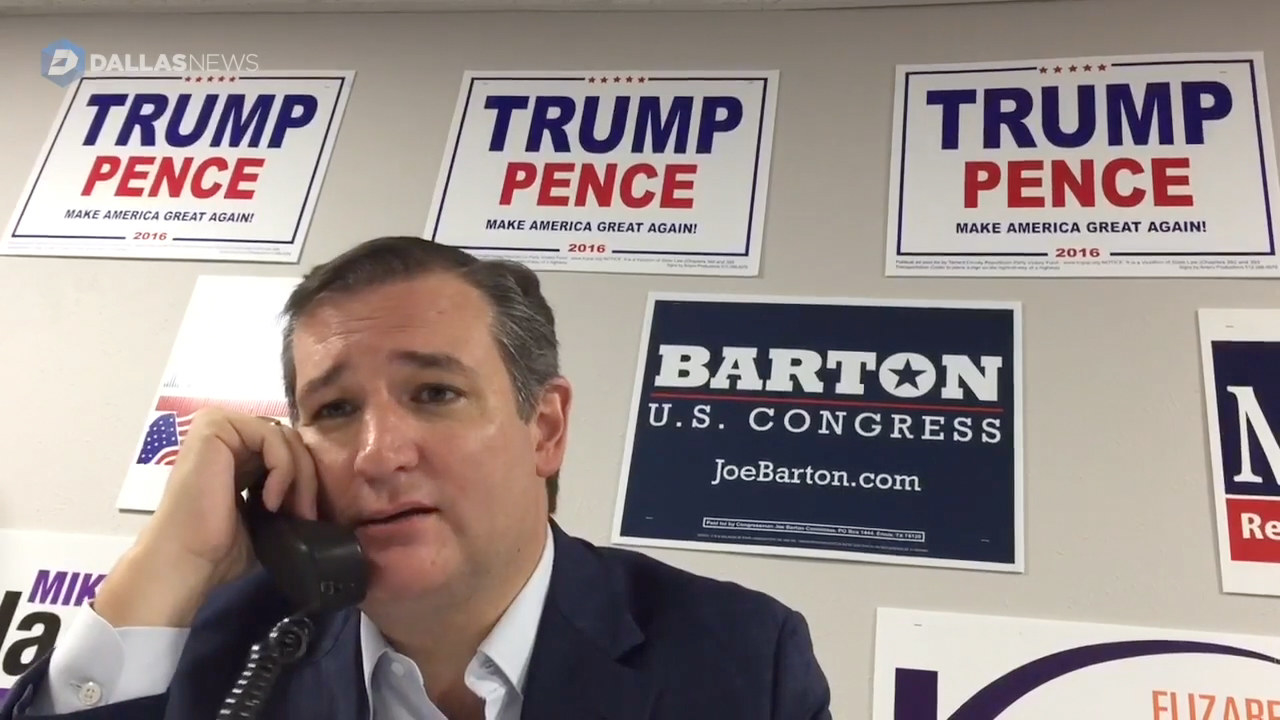

In a twist of righteous/catastrophic luck, when Cruz finally did endorse Trump, the “grab ’em by the pussy” tape dropped right after, producing that sad photo of Cruz phone banking in front of a wall of Trump–Pence signs.

And though he assembled the shell of a 2020 campaign in the fall of 2016 on the premise that Clinton would win, he has not wavered in his support for Trump (with one major policy exception, trade) since. “I could have chosen to make it about myself, to be selfish and say, you know what, my feelings are hurt, so I’m going to take my marbles and go home,” Cruz has said. “But that would have not been the job I was elected to do.”

How appealing it can be — how satisfying it is — to watch Trump destroy the opposition.

Cruz understands, better than most, the direction of politics. Before the 2016 primary, he correctly isolated the attributes Republicans wanted in their 2016 nominee: anti-establishment, conversant in the culture, someone who’d embody an “us versus the elites” paradigm. He understood that white evangelicals and voters against the 2013 immigration effort would decide the primary. And he correctly identified the kind of campaign that would cascade into something more: a movement campaign driven by peer-to-peer organizing, the kind that gave Barry Goldwater the Republican nomination in 1964. Except he wasn’t the guy: Republicans and white evangelicals went with Trump, and Bernie Sanders’ democratic socialism was the movement.

Two years later, as Cruz has gestured toward the right's fringe, some conservatives have retroactively justified their vote for Trump with his administration’s willingness to advance certain causes, like changing the tax code or moving the embassy to Jerusalem or, especially, putting conservative judges on federal courts. But these are all things that Cruz and most of the 2016 Republican field would have tried to do in the White House. They also couldn’t have been most Republican voters’ real top priority, because Candidate Trump would not have repeatedly won a plurality if they were.

“All this time, I thought they were voting for libertarian Republicans,” Rep. Thomas Massie said last year. “But after some soul searching, I realized when they voted for Rand and Ron [Paul] and me in these primaries, they weren’t voting for libertarian ideas — they were voting for the craziest son of a bitch in the race. And Donald Trump won best in class, as we had up until he came along.”

How appealing it can be — how satisfying it is — to watch Trump destroy people.

The point actually is that Cruz took those selfies in the Trump Hotel, and now here we are, hearing about it and watching as Trump campaigns on Beautiful Ted’s behalf. Does our president regret, he was asked, that he accused Cruz’s father of helping murder John F. Kennedy?

“I don’t regret anything, honestly,” Trump said. “It all worked out very nicely.”

Trump’s brutality is what’s mesmerizing — especially when he finds a target that everyone can get behind. ●