WASHINGTON — The Republican Conference is experiencing something it hasn't had in a long time: unity.

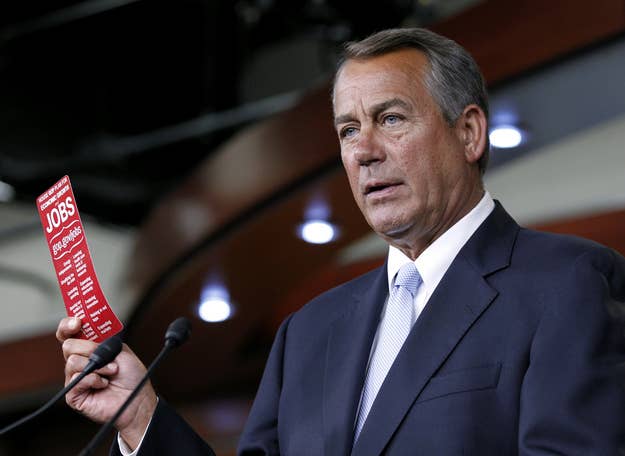

Speaker John Boehner has overseen one of the most bitter and divided conferences in recent memory. Conservatives have consistently, and openly, defied him, while moderates have publicly criticized the rightward lean of the GOP under his stewardship.

But those divisions are, at least for now, taking a backseat to Republican unity, thanks to a series of ugly Obama administration scandals, a lack of crises needing immediate attention, and shrewd scheduling decisions that have kept divisive issues off the floor.

"Yes, Todd Rokita has faith in leadership. We are best when we are bold, it's a new day," said Rep. Todd Rokita, referring to himself in the third person at a Heritage Foundation event. "And I don't mean just because of the IRS scandal — whatever this environment is, it's a new day, it's a new Congress."

"Yeah, I think there's a little spring in our step these days," Rep. Richard Hudson told BuzzFeed. But Hudson acknowledged the reality that all the intra-party love that's going on may be nothing more than a scandal-induced sugar high, and that once Boehner tries to force tough decisions on his conference, it could all fall apart.

"The real test will be the debt limit," he said, adding, "we've got a while to go before then, things could change."

Rep. Justin Amash, who often bucks his leadership and voted against Boehner for speaker, said he was more skeptical of Boehner's ability to keep his promises.

"Trust but verify," he said.

So what's changed from January, when leadership relied on Democratic votes to pass a Hurricane Sandy relief bill and conservatives were openly plotting to oust Boehner?

For one thing, the deluge of scandals over the last several weeks.

For members who have long argued that the Obama administration was heavy handed against its enemies, recent scandals have left them feeling somewhat vindicated. There have been and will be repeated hearings into the revelation that the IRS targeted conservative groups for auditing, and some conservatives have been gleefully saying, "I told you so" to reporters now that it's been revealed the Department of Justice seized the phone records of Associated Press reporters and editors. Republicans have kept the heat on the White House over the terrorist attack last year in Benghazi.

It's not just the scandals that have brought Republicans together. Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy have, with critical exceptions, loaded the floor with easy votes for their members: They've been united on things like building the Keystone pipeline and agreed to again hold a vote on the repeal of Obamacare. And tactically, Republicans say they were boosted and scored a legislative win when they passed the "No Budget, No Pay" act, arguing they effectively forced the Senate Democrats to pass their first budget in four years.

But when leaders have sought to pursue controversial legislation, or even bills that its most conservative members don't like, the results have been embarrassing.

Cantor was forced to pull a bill from the floor that would have transferred money from one piece of Obamacare to a fund for people with pre-existing conditions because conservatives argued it would extend the life of the law they have committed to repealing. Leadership is working to revise the bill to make it more palatable to Republican opponents, Roll Call reported, but so far they've been unable to convince any opponents to drop their concerns.

Aware that the unity is fragile, the conservative group Heritage Action for America sent a warning to Boehner and Cantor, urging them to keep the focus on the scandals and "avoid bringing any legislation to the House Floor that could expose or highlight major schisms within the conference."

"Recent events have rightly focused the nation's attention squarely on the actions of the Obama administration. It is incumbent upon the House of Representatives to conduct oversight hearings on those actions, but it would be imprudent to do anything that shifts the focus from the Obama administration to the ideological differences within the House Republican Conference," wrote Heritage Action CEO Michael Needham, also noting that the GOP shouldn't give the press any reason to shift the focus from Obama "to write another 'circular firing squad' article."

But a strategy built on Obama scandals and avoiding difficult issues can only last so long, and in the coming months, Republicans will once again have to figure out a strategy for raising the nation's debt ceiling — a subject that has divided the conference on more than one occasion. The big question is whether they keep a united front moving into the summer.

Conservatives believe the GOP is in a good position to win on budget and spending issues and have held off from the normal sniping at leadership that accompanies the months before a tough vote, in part because of the so-called Williamsburg accord.

More a capitulation by leadership to back conservative demands for ideological purity, the agreement was brokered during the Republican Conference in Williamsburg, Virginia, in January and requires leadership to agree to a debt ceiling increase only if it is part of a deal to balance the budget in 10 years.

"I think the most united we have been in the past two and half years has been when we do what we said we would," said Rep. Tim Huelskamp, a Kansas Republican and frequent critic of the speaker. "We had a very strong vote on a budget. The next part of the Williamsburg accord is putting that budget into the debt ceiling vote. That was the whole purpose of those votes, finding a way to get into the driver's seat."

Of course, there is almost no chance President Obama will ever even see a debt ceiling measure that fits conservatives' bill. Senate Democrats will never agree to the kind of massive cuts in spending a 10-year balanced budget would require. Even if by some legislative miracle the bill gets through the Senate, Obama will certainly veto it.

"Oh, there's no way we're going to get that," one senior Republican aide acknowledged. The problem for leadership is that they'll need some wiggle room from their conservatives if they hope to get the strongest deal possible for their members.

House leadership held the first in a series of listening sessions with members last week on what a debt ceiling agreement should look like, and already there are some disagreements.

Rep. Raul Labrador, a harsh conservative critic of leadership, said at a Heritage Foundation event that one suggestion to tie the debt increase to only a tax reform bill — and not include spending cuts — was "nonsensical" and a "slap in the face."

"We're going to have to do a lot better than 'No Budget, No Pay,' which I opposed," Amash said. "We still don't have a budget, every member of Congress has been paid, and the debt ceiling increased."

But others said they were confident in leadership moving forward.

Rep. Tom Rooney described Boehner in the listening session on the debt limit as "very attentive" and said that the tides for the conference had shifted in recent weeks.

"I definitely get the sense that things are better. There's some conferences where it's almost screaming matches between people, harsh disagreements," Rooney said. "And that's not been what's happening lately. We have been more on the same page lately."

With reporting from John Stanton.