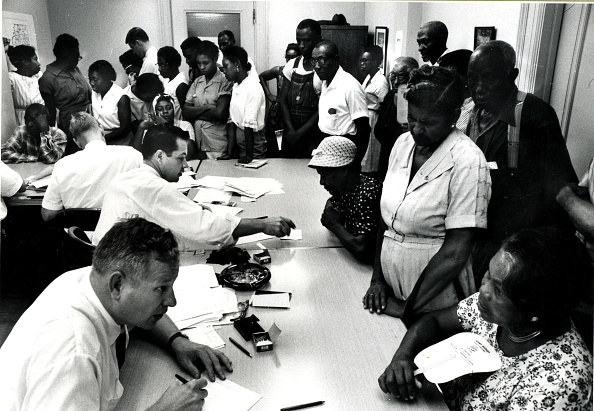

Before 1965, it was perfectly legal in Louisiana to be denied voting rights if you had a child out of wedlock. Across the South, literacy tests, citizen tests, and poll taxes were common, designed explicitly to restrict Black and nonwhite Americans from voting. After the Civil War, the 15th Amendment prohibited denying men the right to vote based on their race, but it did not grant automatic voting rights (women had to wait another 50 years for the 19th amendment in 1920).

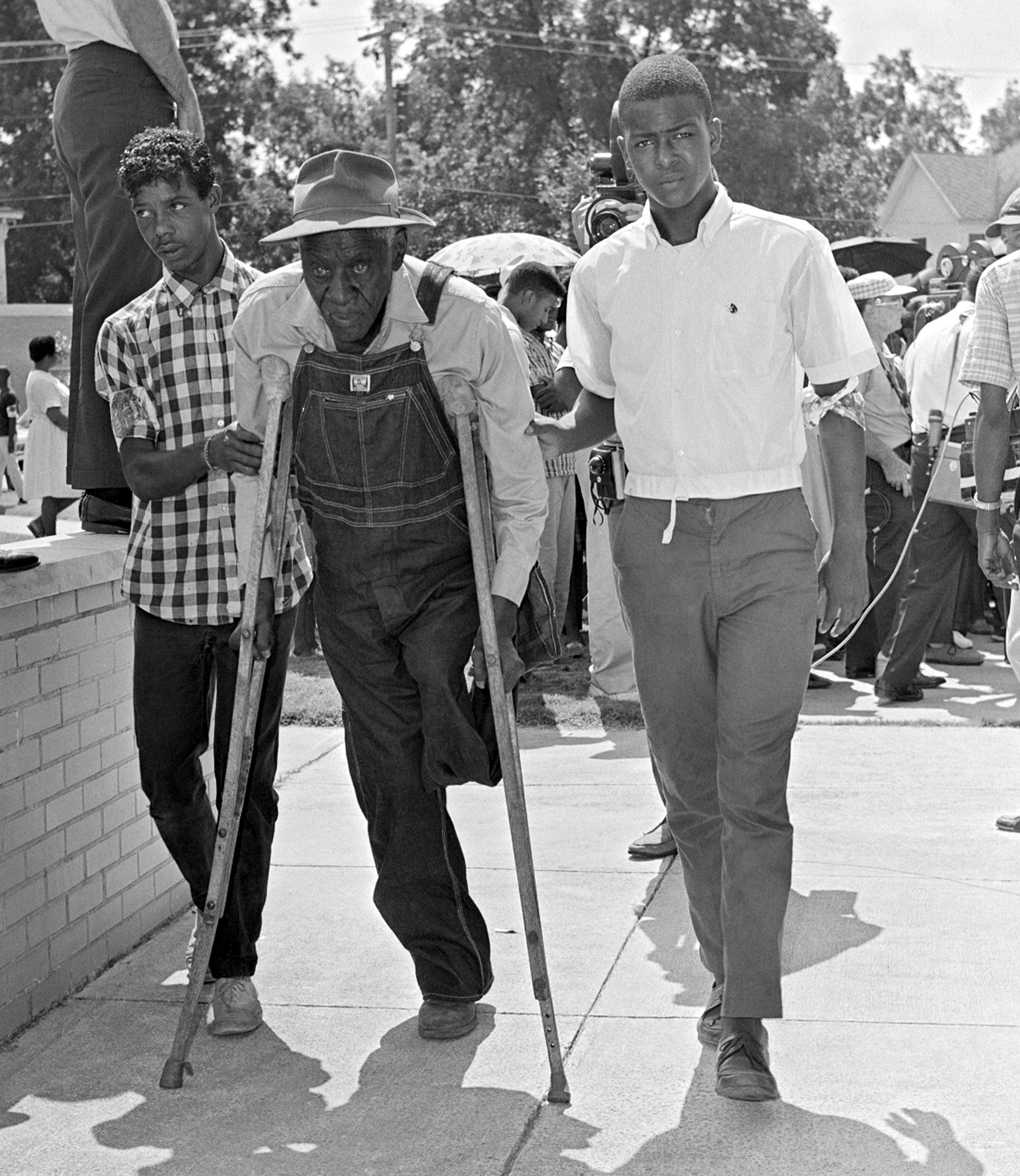

While some men and women could and did vote, laws demanding certain requirements to be met in order to vote led to widespread disenfranchisement, leaving Black Americans in particular with very little say in how their communities were governed. Equal access to voting was a central focus of the early civil rights movement — "Give us the ballot, and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights," Martin Luther King Jr. said in a 1957 speech. The focus on voting rights sharpened after peaceful marchers demanding suffrage, led by John Lewis, were attacked by state troopers in Selma, Alabama.

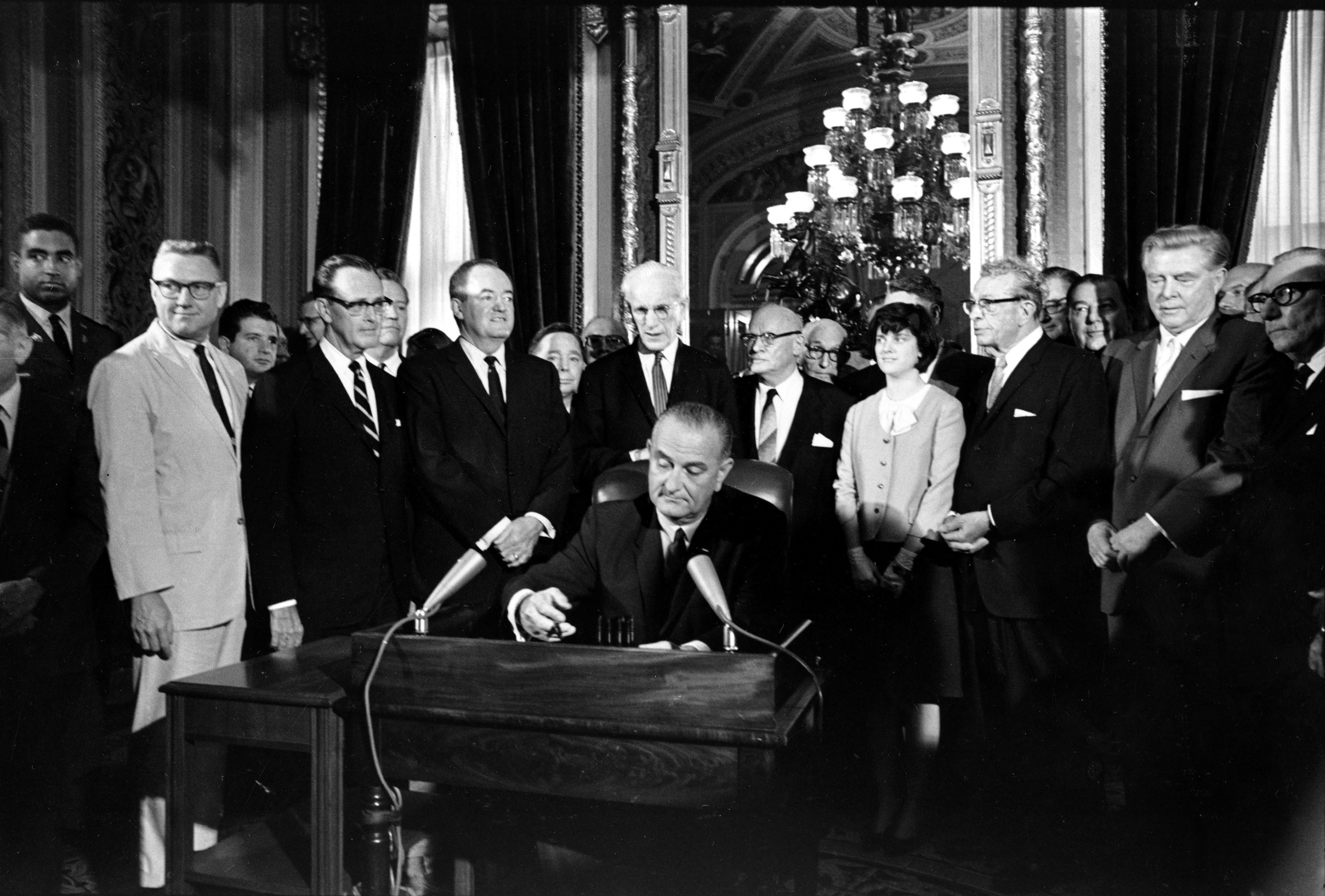

The footage of Bloody Sunday, as the attack came to be known, shocked the nation. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on Aug. 6, 1965, which made it illegal to impose restrictions on access to elections at all levels. The act has been renewed twice since, with 25-year extensions being signed into law by former presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush.

Nonetheless, there is not universal suffrage — felons, undocumented citizens, and permanent residents cannot vote in all states — and in 2013, the Supreme Court ruled that restrictions were allowed, undermining the original intent of the Voting Rights Act.