Many people have covered portions of the border between the US and Mexico, but the complexity of the region is often flatlined to a region or to an idea. To counter this, photographer Elliot Ross and writer Genevieve Allison spent weeks covering all 2,000 miles of the US–Mexico border in detail, and the resulting images are truly stunning, cutting to the heart of heritage, American ideals, and the surreality of modern times.

Their project was born from a desire to see how people along the border felt about the increased calls for a wall from political factions elsewhere, and it was partially inspired by the works from the New Topographics photography exhibition, which examined American landscapes during the Cold War. BuzzFeed News spoke with the pair about their upcoming book, American Backyard.

What was the most surprising about this project?

Elliot Ross: The singular most surprising thing going into this was seeing this core issue of building a wall as not this really divisive thing. Within the national discourse it is, but once you get to the borderland and meet the people who live with the border as a part of their daily life, across the board, rather than it being a divisive issue, it's one that brings people together in opposition. That was surprising to us.

From far right to far left, and for different reasons. The Republicans have very Republican reasons: They want to avoid federal overreach — and the government coming in and taking their land, using eminent domain for the border, is the definition of federal overreach.

For all the thousands of people that we met, we only met a handful who were pro construction of the wall, and that's something that is not really acknowledged. I feel like so much of this conversation is driven when anecdotes are needed from a very few select group of people, most of whom don’t even live in the borderland.

Genevieve Allison: Some of the small rural towns were affected in a completely different way than you would think of in an urban environment. I think one of the more surprising places that we encountered was this tiny place in Arizona. Just one family who occupies what is still designated as a town. It's just a couple of houses in the middle of nowhere, a few on the American side and the rest on the Mexican side. There's no border crossing there, but there used to be — so their neighbors who are on the other side of the border can’t come to visit. There were all these instances where the strange and arbitrary nature of the border really showed itself in terms of the lived experiences, and those were outside of the more commonly represented and referenced places near the border.

The urban areas where the border is more, I wouldn’t say militarized but more heavily surveilled, where you’d have watchtowers and Border Patrol on every corner — there was the repetitive nature of being stopped and questioned every day, and realizing the larger reality of what it would be like to live under a police state and how easily that bleeds into the common course of life down there, how easily we all become so used to showing identification or stopping at checkpoints when leaving. One anecdotal observation that we had was how much more difficult this trip and this project would have been if we looked Hispanic, and how there is heavily enforced racial profiling. That is something that we’ve all just become used to.

What was the journey like?

ER: There was definitely a lot of frustration. We were determined to do every inch of the border, rather than just the highway corridor or just the hotspots that are well-visited. The border is 2,000 miles, and we ended up driving 10,000 miles on this trip.

Securing permission from Homeland Security to be able to drive the border was critical, but just because we had that from DC didn’t mean that the communication was efficient or effective in terms of section chiefs knowing that we were coming. By the time we got to Arizona, we had a reputation with a lot of people — with no one thinking we would actually complete the journey.

Also, a lot of really uncomfortable nights sleeping in a Walmart parking lot for a month on end — being really hot and doing it on our own dime, with no savings or anything. So that was a part of the experience.

GA: A lot of gas station tacos.

ER: That reality also put us in contact with a lot more people, because we were coming from a place of vulnerability. And in a lot of ways that's disarming.

Why is this book called American Backyard?

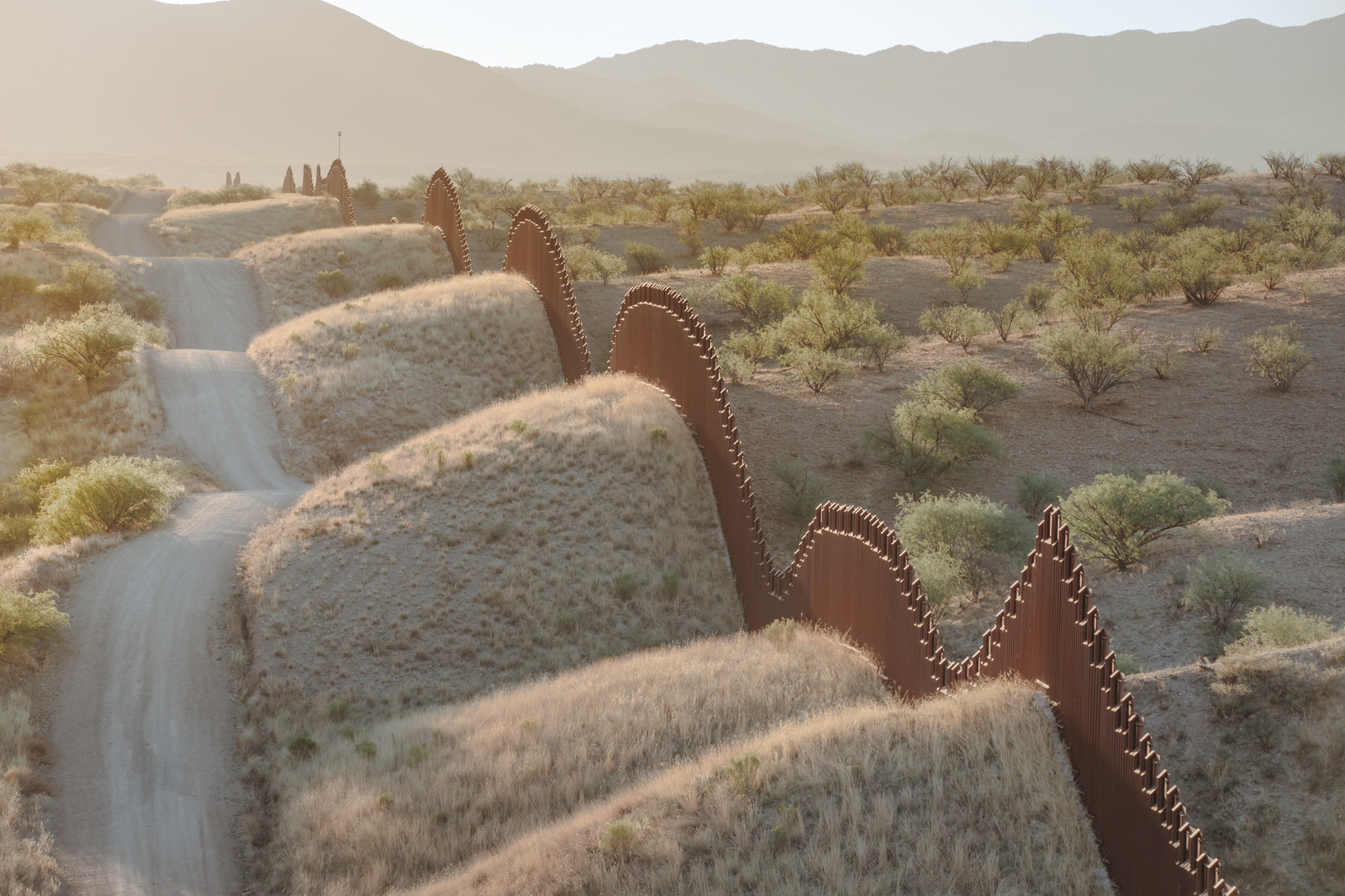

GA: When we set out on the project, initially we were really interested in looking at families whose backyards' perimeter was actually formed by the border wall. And there were some really fascinating examples of that, how naturalized and quite hideous the wall could be.

We expanded on that whole idea to encompass the lived experience of just getting along, living your life, and having all the comforts that we really prioritize with home ownership and private domain. The conflict there resonates out in a more macro sense in how we think about public and private domain, and how we think about our neighbors and what it means to have a fence and have to defend it.

ER: And it's part of the American dream that has driven people to cross the border in the first place.

GA: Yes, how woven the immigration debate is into the American dream, and how weaponized it's become, has led into this right or this aspiration to fiercely protect what is yours. Especially with a lot of the borderlands having been Mexican territory, which was actually stolen — all of these narratives overlap.

Can you talk about an image that really exemplified this project for you?

ER: The image of Jamie, the girl in the quinceañera dress. We had met her father in the parking lot of Home Depot while having car trouble. For personal reasons, [that image represents] how much that family meant to us and how helpful they were, but also just that realization of how quickly this situation that Trump has created could be normalized and continued. Jamie said that she didn't even see the wall anymore, that it was just a feature of her life.

GA: It sums up this project with the confluence of serendipity and intention, of building relationships, but also having the subject be representative of a generation and their heritage. There is this renaissance of this pride and the cultural belonging that people don’t understand about the border that is all present in this image of a 16-year-old wearing her quinceañera dress.

It's also what's at stake for this generation being brought up and it never being obvious to them that they don’t need a border, they don’t need a militarized front with their southern border and the inherent xenophobia that comes with that. I think that image really straddles the documentarian approach and also the artistic sensitivity and the mood and our intention to not glamorize or romanticize but point out what is quite beautiful and delicate about this place.

ER: One thing that we kept hearing over and over, especially from the older generation who were disheartened by the current state of affairs, is just how vibrant the relationship between both countries was in the past and how much that brought into their lives in terms of culture and these relationships and food. This area really thrived from that influx of ideas and approaches to life. And the wall, this singular thing, threatens all of that.