A version of this interview appeared in our photo newsletter JPG. Not a subscriber already? Sign up!

John Pfahl was a fine art photographer based in Buffalo who was known for his innovative landscape photography, which often used optical manipulation to make unique, and playful, images that reflect on the relationship between man and nature. After Pfahl died of COVID-19 in April of this year, we spoke with Janet Borden, his longtime friend and gallerist, about his work.

Can you tell us about the Altered Landscapes series?

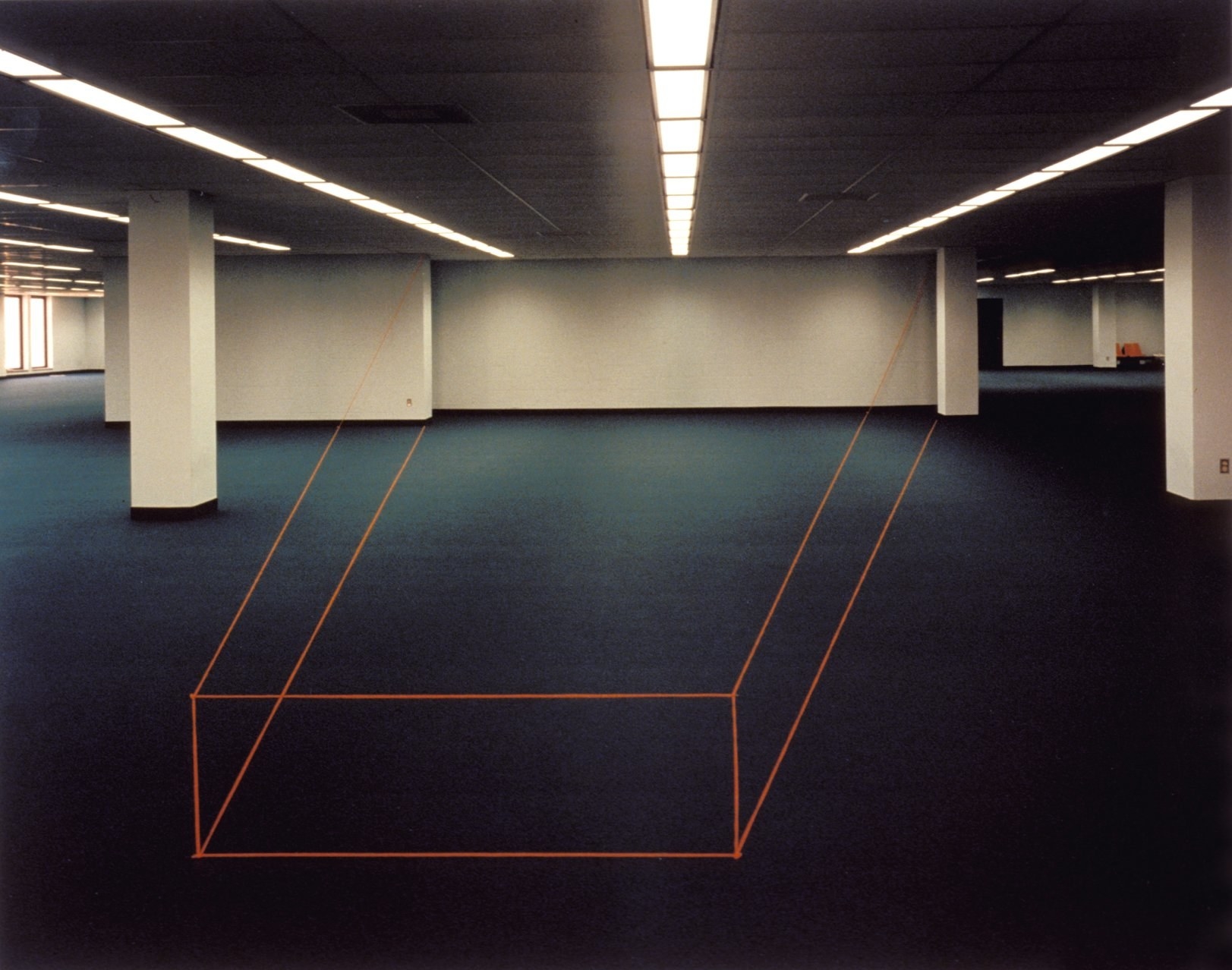

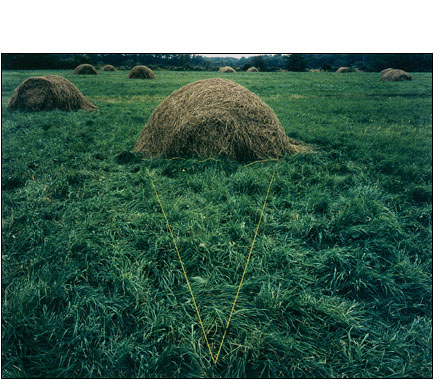

He was fascinated with the way the camera interprets what's in front of it. And it's a photograph vision in these cases, all of these setups are total illusions that only work from the vantage point of the camera. So like the aluminum foil on the tree, "Australian Pines" it's called, that's probably 6 feet of aluminum foil wrapped around each tree. They're all very elaborate setups that only work photographically. If you're standing there, it doesn't look like that. It's really smart. He likes to make it look silly, but it was really cool. We always used to say that he was “smart, pretty, calm,” but that's a great combo.

They're all done with a 4-by-5 camera. He could just figure out how to do it, and then he would have assistants with help sometimes just so he didn't have to run back and forth all the time from the cameras to check it out.

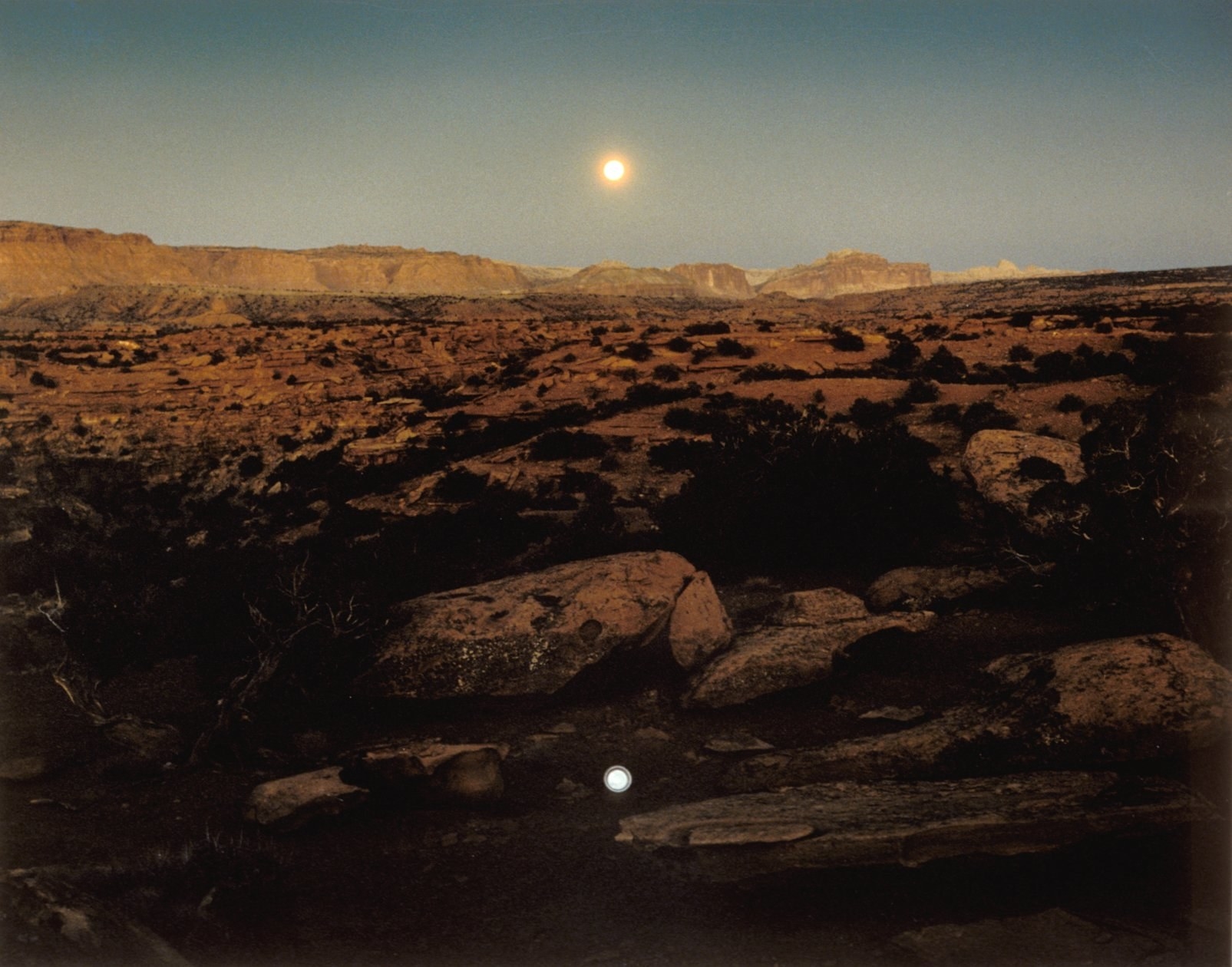

He wasn't just interested in taking pretty pictures. For instance, he has that really funny one, "Moonrise Over Pie Pan," making fun of an Ansel Adams photograph. But his picture is just as pretty, you know. It is a good pastiche, but it's still gritty; it's still beautiful. And he usually would sort of have some sort of conceptual overlay, I would say, to each of his projects.

Did he think a lot about how humans interact with landscapes?

Always, always, always, always. The nature ones are always sort of about that, and the power places were really quite shocking, because they didn't look like that. He did another series called smoke, and they were really beautiful cloud landscapes, but they're all that sort of toxic smoke being blown out of Bethlehem Steel and blown out of companies.

So he was always, you know, a conservationist, I would say. I think what he loved is that push-pull between humans and nature.

Can you talk a bit about his other projects?

There's a wonderful collection called Power Places. He went around to places where there were nuclear reactors. He would make a beautiful landscape with that in it, and it was the idea that you would incorporate this frightening concept into the beauty of the landscape.

It would be ridiculous for a person in the year 2000 to take just a pretty landscape, you know?

Ridiculous isn't the right word. I guess I think that that would just be sort of banal.

You know, that's sort of what separates art from snapshot. I could go on forever about that difference. The intent is very important in art, and people forget about that.

The world is more interesting than any of my opinions about it. What photography does is it shows things in a way that talking about them doesn't. It takes great effort to make things look better, especially altered landscapes because they just look simple.