Edward Burtynsky, a legendary landscape photographer, has spent the past three decades looking at how resources are used and the impact of humans on the environment around the globe. He collaborated with Nicholas de Pencier and Jennifer Baichwal on his newest project, Anthropocene, which combines scientific research with film, virtual reality, augmented reality, and photographs, and is also available as a book.

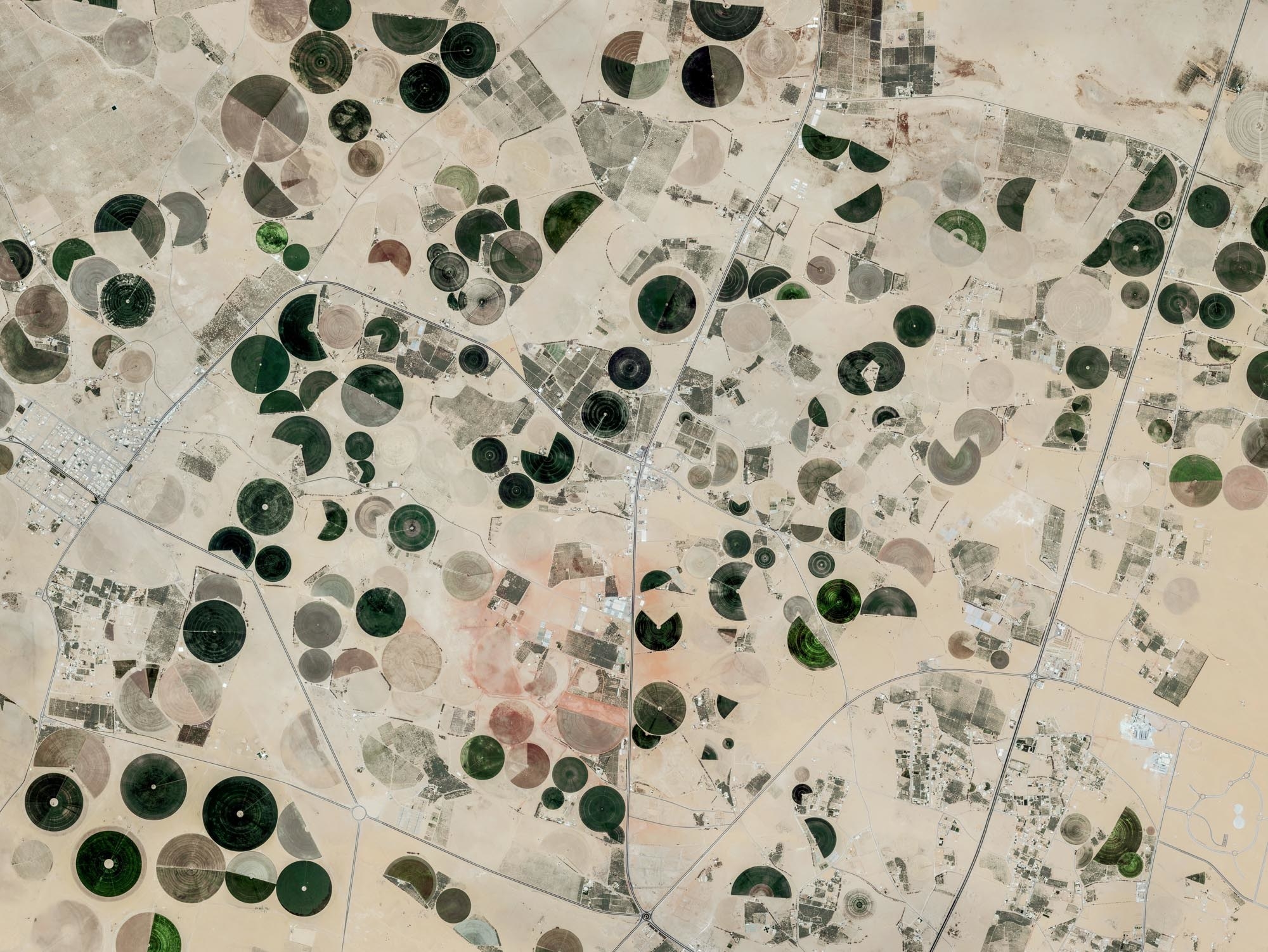

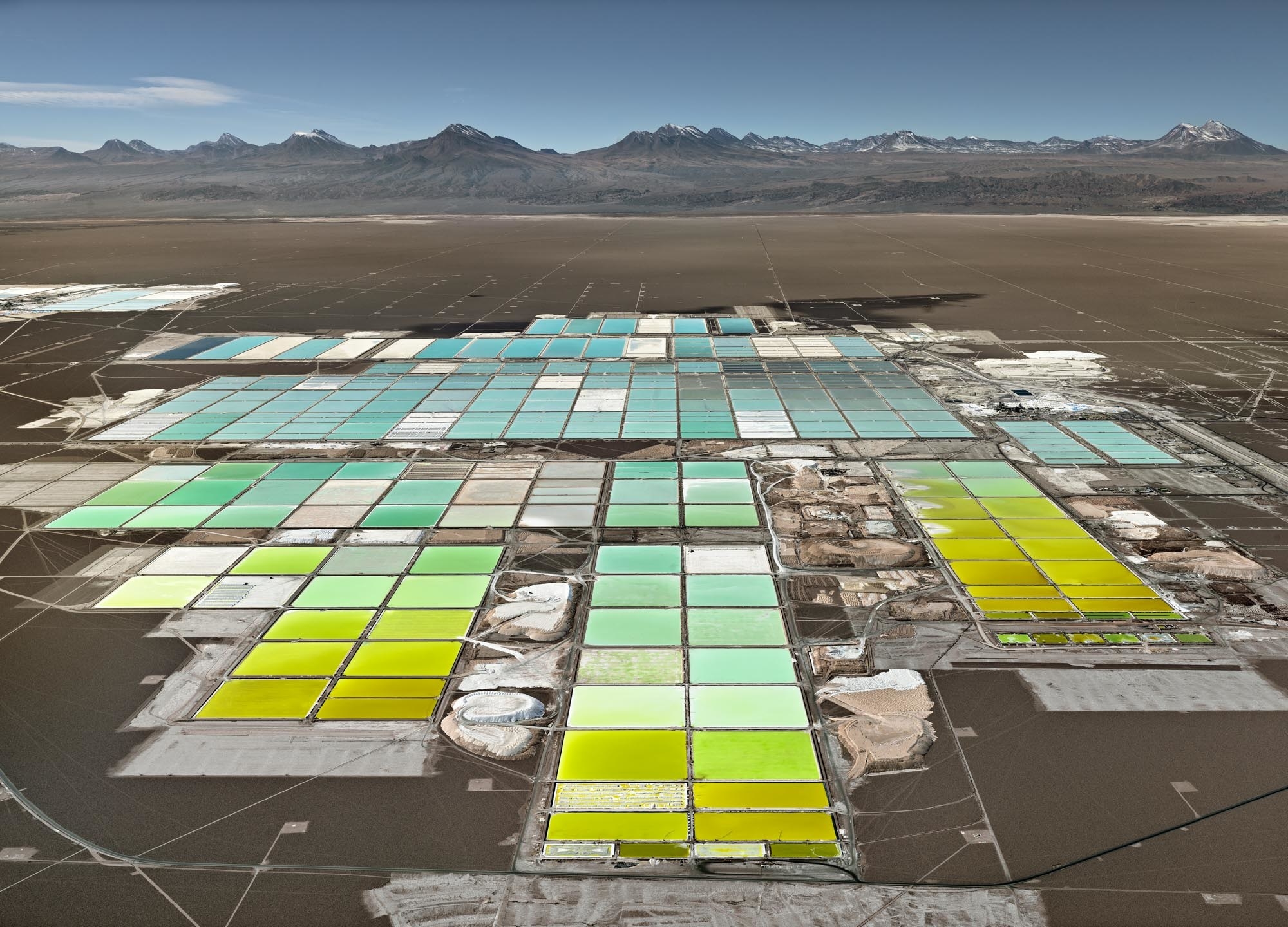

The photographs from the project are both haunting and eye-opening, offering a unique perspective on the collective result of decisions around the globe. "I have come to think of my preoccupation with the Anthrocepene — the indelible marks left by humankind on the geological face of our planet — as a conceptual extension of my first and most fundamental interests as a photographer," he says in the book's introduction.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity, and originally appeared in our photo newsletter JPG. Not a subscriber? Sign up here for exclusive interviews and inside looks.

How did you get started on this?

I think that started really in 1980–81. I was interested in hyper-realistic work and saw photography as the ultimate realist tool. I liked the fact that there's large negatives, which captured scenes in such exquisite detail that I can make large prints and every detail, every blade of grass, every tree branch, is finely articulated. I was first looking at nature and trying to mold it in a very kind of painterly way.

I then felt that there's an interesting project that speaks more directly to my time, which is how we shape nature and how we usurp nature and how the forces of consumer capitalism work. Back in the early ‘80s, we're going to extend further and further into nature. Consumer capitalism sees nature as a cupboard to go and get things from, and I was looking at the scale of that object-taking in that cupboard.

That was a more interesting approach to landscape. It's not the landscape of nature but of the landscape of human systems, systems imposed in nature to harvest the things that we need. So I sent out and went off on a kind of lifelong pursuit of capturing the largest-scaled human systems on the planet.

Did you know that this was going to be a lifelong project?

I sort of in my head said, Yeah, this is inexhaustible. There are just new ways of looking at it, and the world's not changing.

I suppose the thing that that's missing is, we base the whole economic ideal on growth, and nothing grows infinitely in nature — it's impossible. So the graph works. This kind of wonderful, invisible hand of the market works when the resources are there to be able to support all of that, but we live on a finite planet. We just can't infinitely keep growing our population. We can't infinitely keep going to the cupboard.

Of course, there's a counterargument that says, Well, you know, we'll just invent new ways to make things, because we're very inventive. And there's some truth to that. But nonetheless, there are problems of massively reduced biodiversity, and to cut off primal, primary forests that are easy for us to cut, but where most of the biodiversity already exists. We could maybe invent some ways to grow food in labs or whatever, but we're still gonna need stock. We're still gonna need resources, no matter what we do, if you want to grow things and allow others to do things. It's a question of sustainability.

None of us can be totally isolated, unless you go off the grid and live off the land. But we all can't do that either. So we find ourselves in this dilemma of modern existence, where we know what we're doing is having a significant collective impact on the world, but we're not coming up with the antidote to this problem. We're starting to grapple with the problems more directly, but it's always as some kind of crisis, fires and weather, now it's this epidemic, which is largely part of globalism, and a part of, again, overreaching, being too close to wild animals.

Have you seen evidence of people having a lighter impact on the world?

I don't think a lot, quite frankly, has changed. Even with all the warnings in the last 20 years, it's business as usual. But I do think that there is a pre-seismic change in attitudes and approaches. I started seeing that happening in the big urban centers, which are very much going back to a lighter touch, veganism and such. And there is the idea of wellness, I think if people begin to treat their bodies with respect and what goes into them as important, that by nature extends into your world around you, and into a healthy environment, because you can't have good clean food if you're applying pesticides. I think that what's happening with the millennials is interesting. Healthy mind, healthy body.

Has the reaction to your work changed?

Now, you can't turn on a TV station or a radio program or open up a newspaper today without somebody telling you somewhere that we've got a problem, whereas 15 to 20 years ago nobody was talking about it. There was a lot of talk in 2006 or 2007 when An Inconvenient Truth came out, and I thought, Okay, this is it. This watershed moment is what we've all been waiting for, thinking it was going to be the beginning of a new era, and it just kind of got sideswiped.

I'm just hoping that doesn't happen this time. Greta and all that stuff that happened in the last couple years has brought climate to a fever pitch, and I don't know, in a year from now, are we going to be talking about climate, or are we going to be talking about the economy? Because there is a relationship. If we're going to deploy a lot of future earnings from future citizens and bring the money now, why not use a good chunk of it to build a world that they can actually live in?

Photos © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery and Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery, New York / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto.