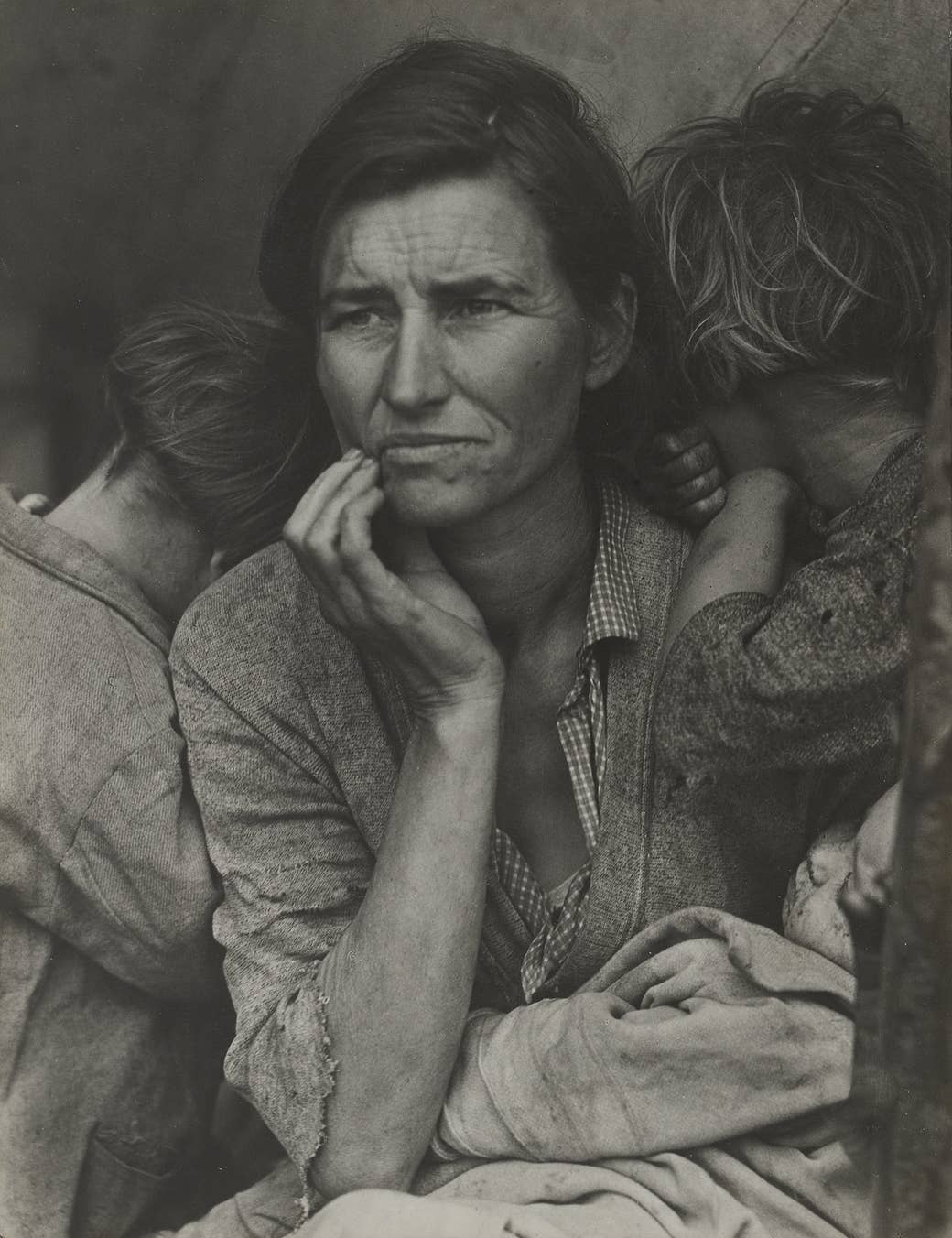

Dorothea Lange may be one of the most iconic photographers in the history of the world. Her most famous image, known as “Migrant Mother,” was taken while Lange was in government service during the Great Depression and has been used widely in ads, book covers, and historical documents. Her empathetic, thoughtful eye documented Americans across states and classes and provides a window into an era that now more than ever feels akin to our own.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City has built an exhibition of Lange's work including commentary from writers, artists, and scholars that feels incredibly relevant for the present time. Although the museum is closed, the exhibition can be seen online, along with an audio guide detailing some of the images included. BuzzFeed News spoke with Sarah Meister, the curator of the show, Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, about Lange's work and why it still resonates.

To start, this exhibition is called Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures. Can you tell us a bit about it?

I knew that she would be a wonderful subject for a retrospective, and we hadn’t done one of her work since 1966 at the museum, so it had been a long time. As we started, her politics, her commitment to looking without sentiment but with deep empathy at human suffering and injustice, made me realize not only do I want to look at Lange, but structuring it around words and pictures seemed like something that curiously hadn’t happened before.

It was an extraordinary exercise to think about what the impact of Dorothea Lange's photograph “Migrant Mother” looked like, to focus on an image as a singular work of art, even one that was basically circulated in more forms and contexts than any other form of art in the history of the world.

What also struck me was how resistant that photograph was to words. It had been associated with many, many different titles and captions over the course of its lifetime — poetic and polemic and aesthetic and news-oriented — and it was as if it didn’t matter what anyone called it, or what words were associated with it. So that got me thinking about words, and that particular picture, and that extended to thinking about Lange and words and pictures in general. And there were two other pieces of this that led me to think of words and pictures as the kind of structuring framework for this exhibition.

One was Lange’s oral history in the ’60s. She said all photographs can be fortified by words. And I thought, huh, all photographs? I don’t even agree with that statement, but more importantly, for a photographer, not a writer, to say that made me think that I wanted to reflect on words and pictures more with Lange.

She made an extraordinarily important photo book in 1939 with her husband, Paul Taylor, who was an agricultural economist, called An American Exodus. And in that book, it's an extraordinary weaving together of words and pictures, both contextual words that give you more information than you might see in the pictures and also words that represent the voices of the people pictured. That idea of an authentic representation of voice was almost as radical as the idea of attention to these people who were really suffering during the depths of the Great Depression.

So all of these things together — the migrant mother experience, her book American Exodus, and her own thinking about words and pictures — led me to believe that instead of just looking at Lange and doing a straightforward retrospective, which would have its own merit, the commitment to Lange was there, and I knew we had an extraordinary Lange collection.

How is this different from a traditional retrospective?

One of the things that we were really keen to do was to make sure that the exhibition wasn’t anchored in the distant past. As important as a reconsideration of the Dust Bowl and the depression [is], we wanted to underscore the contemporary significance, and so to that end, we developed a list of contemporary writers, artists, thinkers, and we were hoping that some of them might be willing to think about Lange today with us and to add new words to her pictures. To my surprise and delight, of the 12 individuals that we asked, all 12 said yes. And that is as perfect an illustration as any of the way in which her work is speaking to so many people today.

And their contributions really bring new insights and new perspectives, not only in terms of what’s written and included in the book, but also at least four are on the audio guide on the website. They are speaking not only to the photographs in the book but also to other ones.

The audio guide is pretty great too. The idea was that it should really feel like you’re being pulled through a story in a different way, unlike walking through an exhibition or reading a book. There are 15 stops on the audio guide, and when you listen to them end to end, it really does give you a sense of how the spoken word inflects our approach to pictures. My hat’s off to our education team who put this together.

There’s also, on the exhibition page, an intro video that these two young filmmakers actually hired actors for, and we’d never done that before at the museum, to render the voices that Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor had captured in American Exodus. And their ear for dialect, and how it’s rendered, then allowed these actors to read these words with such an extraordinary anchor in a remote time and place. It also includes Lange’s voice.

How did you approach Lange's widespread legacy?

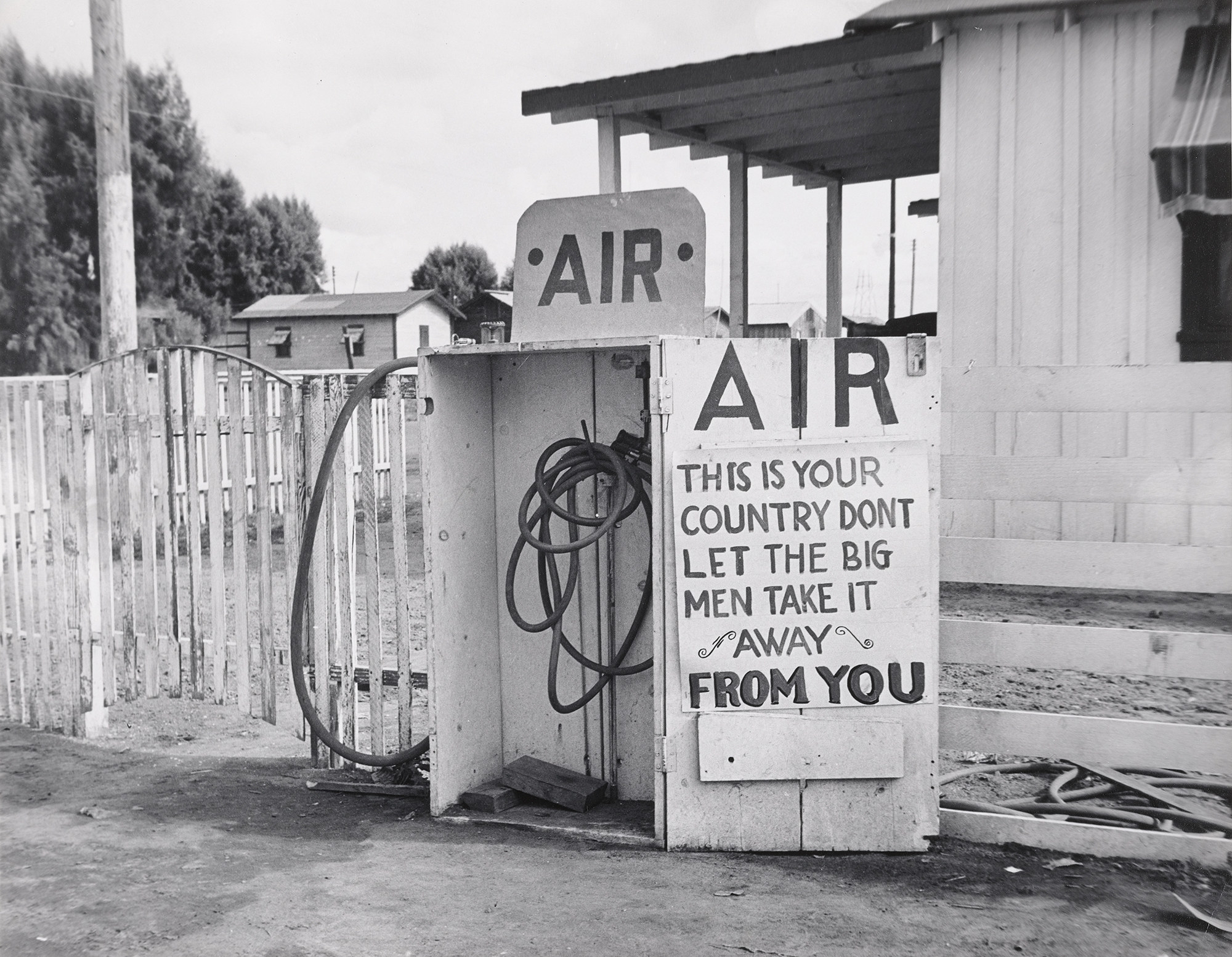

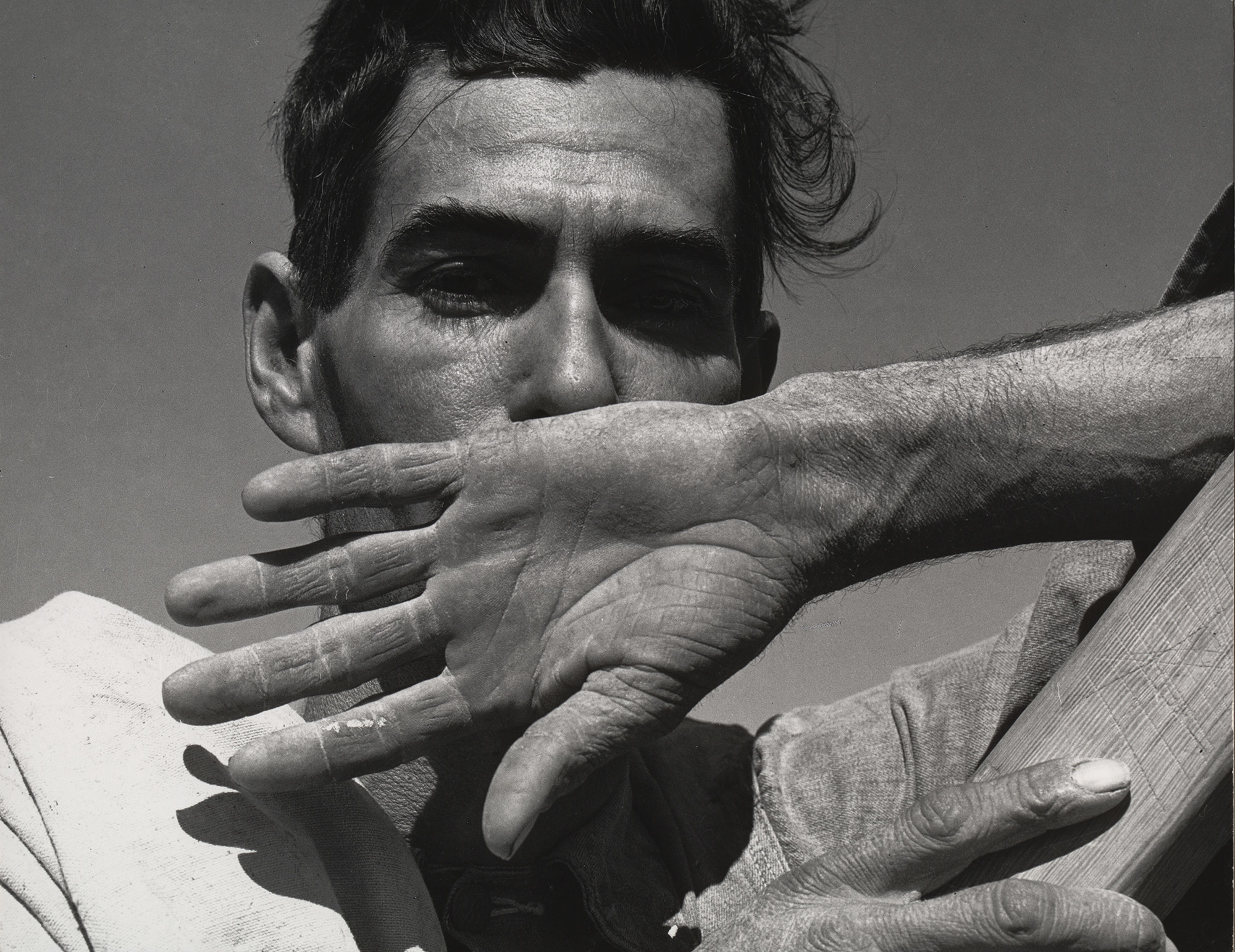

She is known as a photographer of people, and that’s well deserved, but she also understood how people could leave the imprint of people in the landscape, and whether that’s the landscape in the traditional sense or the remnants of people: signs and posters and billboards and announcements. She understood that to represent humanity, it wasn’t only told through the human face — although that was a central aspect of her attention — but also that people’s concerns and people’s lives were also effectively conveyed through the things that they created and left around.

In the government work section in the beginning, she’s showing the shelters that people built and how they bathe, where they go to the bathroom, how they protect themselves from the elements — and these are as revealing, or they can be as revealing, of desperate circumstances as people themselves.

If I’m being really honest, it wasn’t difficult as a curator to find a balance because it's there in her work, and fortunately the museum’s collection is so rich that we were able to find — whether it’s the photo [of the] tractor out where the deep, furrowed, infertile land is plowed up to the door of the likely abandoned house, or in the signs by the side of the road where you see what might have been — the disconnect between [what] the advertisement agencies are marketing to and the realities of these people's lives. She did it so well, it made it really easy for me.

What do you hope that viewers of this exhibition take away?

Just as the time when Lange worked was one of extraordinary challenge and deprivation and injustice and suffering, we, every day, think about what her work brings to our current thinking of the world. I am humbled by the brilliant words all these people wrote about Lange's work, so I will quote them.

There is one photograph that she made called “Grayson, San Joaquin Valley, California” that is of a corpse in the doorway of a church, where the top half has been wrapped, but the feet rest almost as if they are crossed in relaxation. Kimberly Juanita Brown wrote, "Immersed in the banality of death and the gravity of life, images like this one surpass our requisite command of the visual, they haunt us like a book-length poem memorized over time."

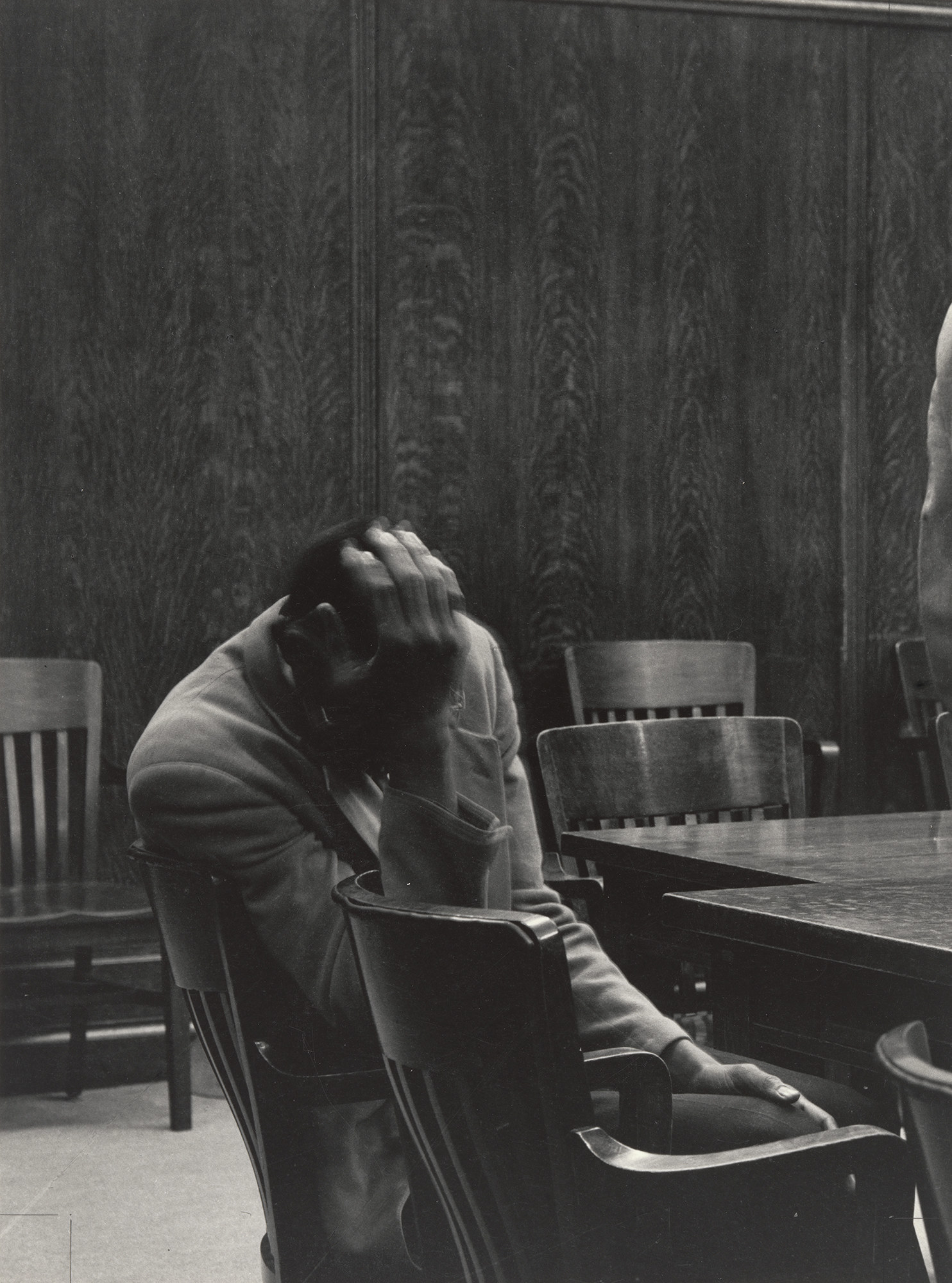

Sally Mann wrote about an image from a series of photographs that Lange did on the public defender system in California. The picture is completely in focus except for the blur of his fingers. Sally took one look at that and said,

"This picture is roaring; we are dying.

We die of the piercing shaft of wall-panel joinery that plunges straight into the bowed head. The unsparing seat of the wooden chairs, with their jail-cell vertical elements. The poignancy of the pressed hand. We are dying of the grief we share with all too many defendants, the helplessness and desolation on the other side of silence."

I find myself thinking of all these people unfortunately suffering and dying, and how Lange’s photographs, they bring us one step closer to being able to think about this and to help us understand how art helps us process suffering and grieving and even death. And for that, I feel so grateful to her, and to think about this.