Go Nakamura, a Houston-based photojournalist, has been one of the photographers covering the medical frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nakamura, who relocated to Texas just over a year ago, has visited the United Memorial Medical Center more than 20 times since May, documenting the caregiving in the COVID ward in a searing series of photos for Getty Images.

As the death toll in the US on Monday surpassed 300,000 people since the pandemic began in March, BuzzFeed News spoke with Nakamura about the experience of, including one of his images that has become an iconic scene from the pandemic.

This interview initially appeared in our photo newsletter JPG — sign up for exclusive access and interviews.

First, how did you get started in photography?

I started as a wedding photographer when I was 28. Before that, I didn't know anything about photography. I was an office worker, and I was just working like a robot. One day one of my friends, who was a very good wedding photographer, said why don’t you try working with me — it's fun, and every day, every client is different. After a few years, I decided I am not really into wedding photography, I wanted to do something else with these skills.

I moved to New York to look for some opportunities and visited this exhibition about Robert Frank, The Americans, the photo book. When I was there, I felt like lightning struck me or something, I thought to myself, this is what I want to do, this is what I want to follow.

Back then I didn't know any editors, or anyone in the journalism field, I just started to go out in the city to take pictures. After four years I still didn't know anyone, but one of my friends introduced me to this photographer, John Roca, who was a tabloid photographer who had been working for the NY Daily News for over 40 years. I asked if I could come with him as he was working — I did that for about 10 months, and one day he told me, "I think you’re ready, so I’m going to start introducing you to editors." So that’s how I got started in the photojournalism field, that was five years ago.

Can you talk a bit about working in the hospital?

I actually have no idea [of] anything besides the COVID world, because I haven’t done any other work in the hospital. In the COVID unit, they usually have 20 beds. The first time I visited, the beds were almost full, and then as I went back over the summer, they expanded the ward so that by now, it's about 30 beds.

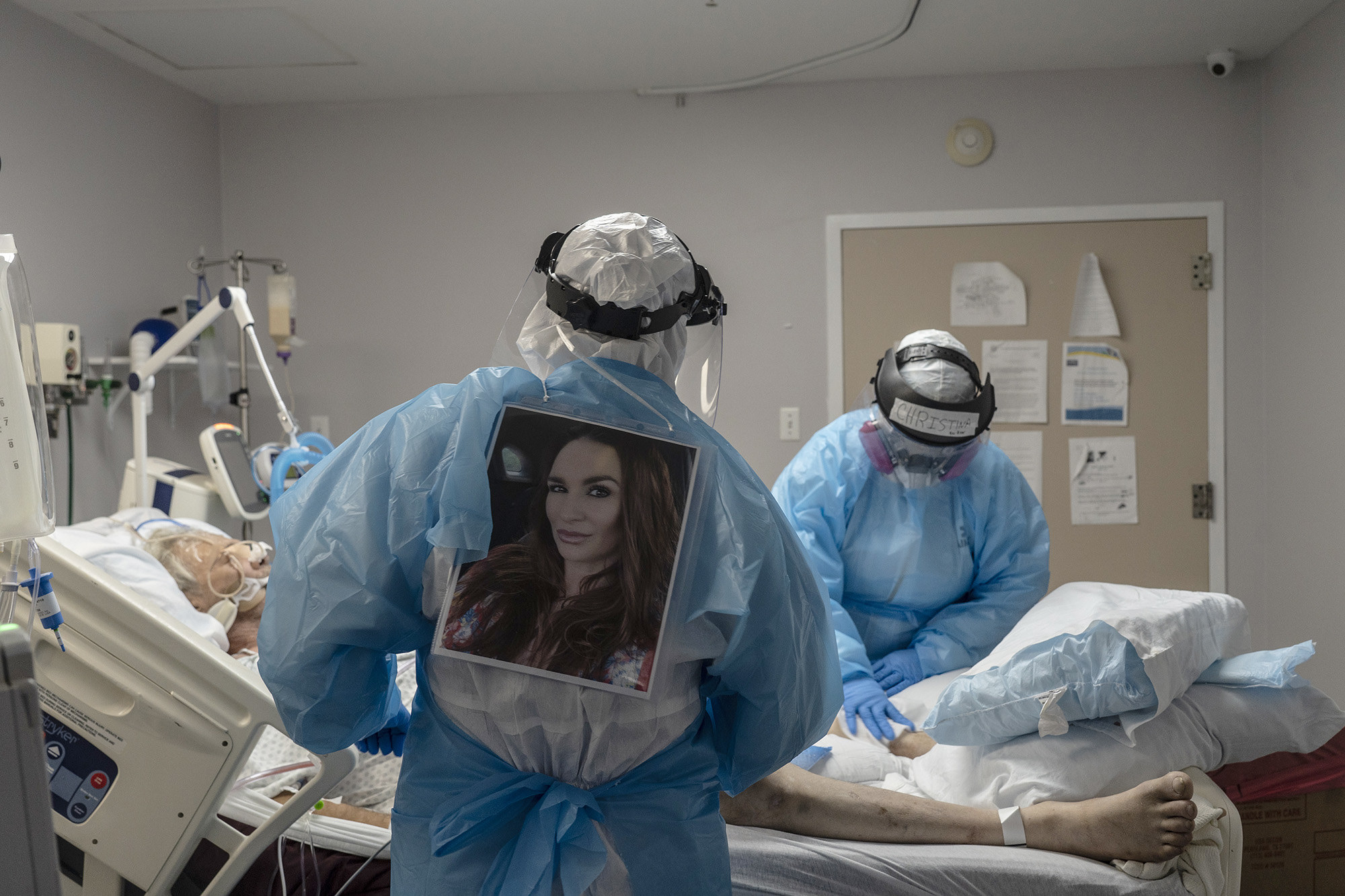

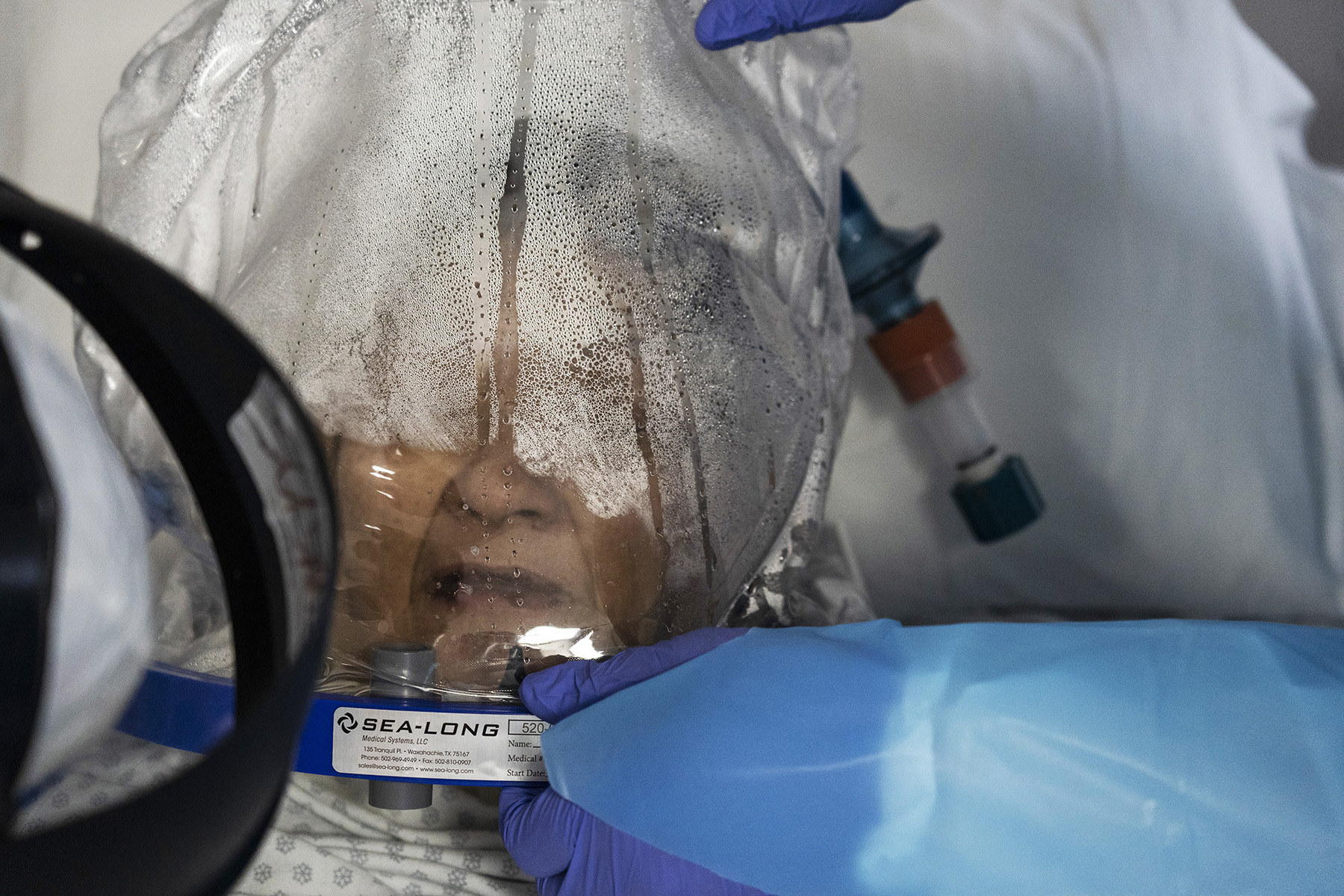

I have to be covered by all the PPE, and there are a few rules I have to follow in the COVID ward. I cannot take pictures of things that show the patient's name. When I go into the COVID ward with the doctor, he asks the patient for me if I can come in with him. Many of the patients are unconscious, but those who are conscious will say no or yes. Those who say no, I wait outside. For those that say yes, I have been strictly instructed that I should not take a picture of the faces of the patients, so every time I take a picture I hide their faces behind the devices, IV pumps or electrocardiograms. I think if I could just show the faces of the patients it would be a much stronger photo, and much easier for me to frame. So it is a challenge.

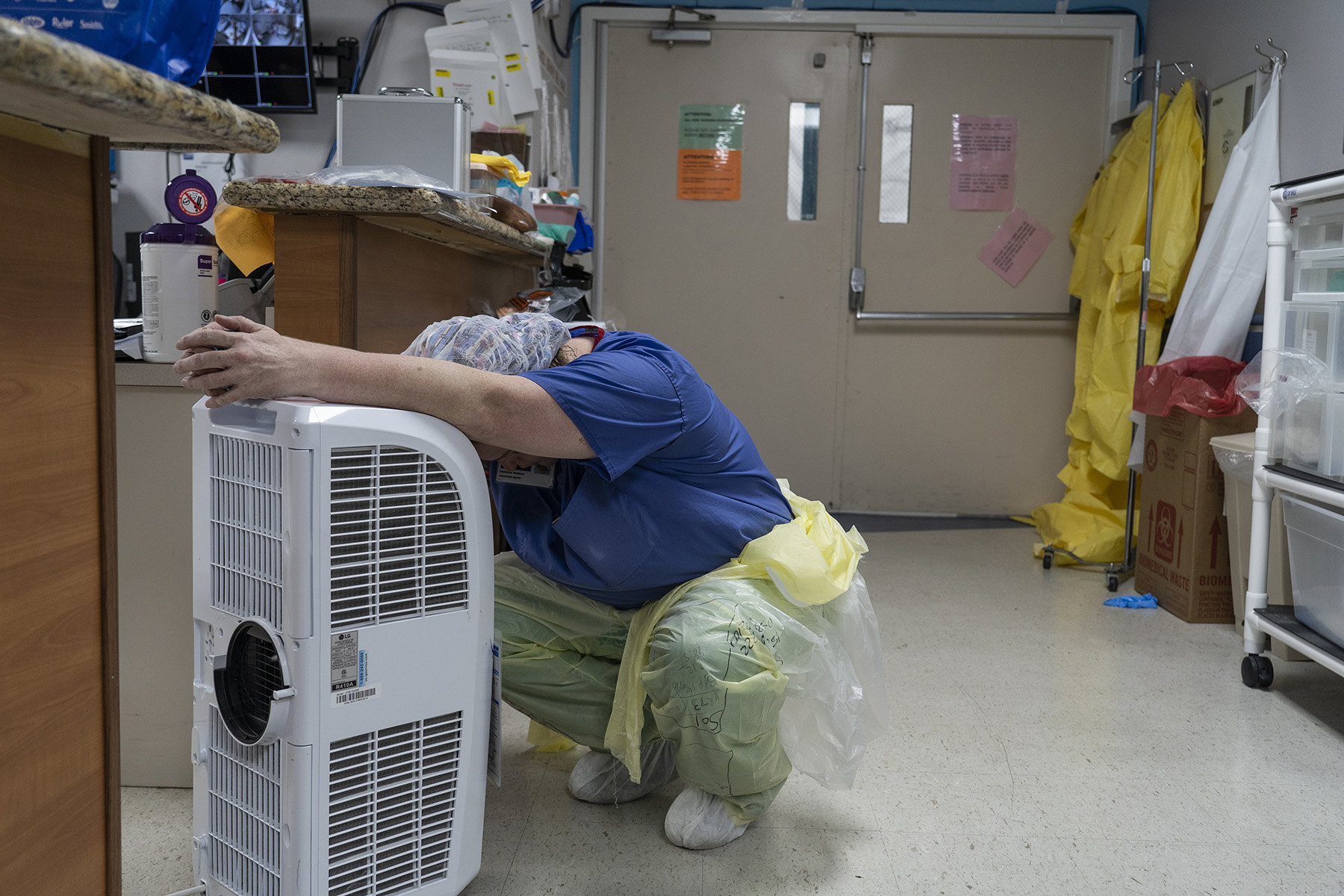

When I am in the COVID ward, adrenaline is pumping, and I can hold it together and focus on shooting. When I get out of the hospital and look at the pictures on the computer screen, that's when it hits me so hard.

I have access to trauma resources through Getty, and the doctors and nurses themselves have been so helpful. The very first time I went into the nurses station at the hospital, Dr. [Joseph] Varon came to the door and invited me in, and started to introduce me. The medical staff were talking and laughing with each other, and I thought this is a very good environment, a fun workplace, and five minutes later, the doctor turned to me, looked directly into my eyes with a very serious face, and said we try to laugh off everything, because otherwise you would go crazy.

One of your pictures of Dr. Varon holding a patient went viral after Thanksgiving — can you talk a bit about that image?

The patient, who really wanted to go home and see his family, misunderstood me as a medical worker, because I was covered in PPE. He seemed vulnerable and was clearly lonely. I called other medical staff to help him, and after that the doctor came in. This patient was recovering — most patients, they can’t move from the bed, but he could stand and walk around the room by himself, but still wasn’t approved to go home. Fortunately the patient went home, about a week ago, I guess.

When I saw the doctor's eyes in the photo, I could imagine, of course he wants to do anything he can to help the patients. He is always trying to give the patients cheerful words. When I shared the hugging photo on my Instagram, I saw so many comments — I was very glad that the photo went viral, because people were talking about the situation, and what they can do.

What would you want a viewer to see in your work?

I’m a photojournalist, and I am doing this job because I want the people to know what is really going on inside the hospitals. It is very rough inside. I am not a medical specialist, so I am not used to seeing the harsh stuff. Sometimes I want to cover my eyes, but I have to take the photo, and I want the people to know how others are struggling — of course the patients but also the medical workers. They are exhausted. Exhausted. I think that Dr. Varon has been working for more than 260 days straight, and the nurses since the beginning of summer with no days off. They have been working so hard. If I can get the pictures out there, and I appreciate that many people can see these, I want to let them know what is happening inside, and what they can do to improve the situation. I want viewers to think about that.