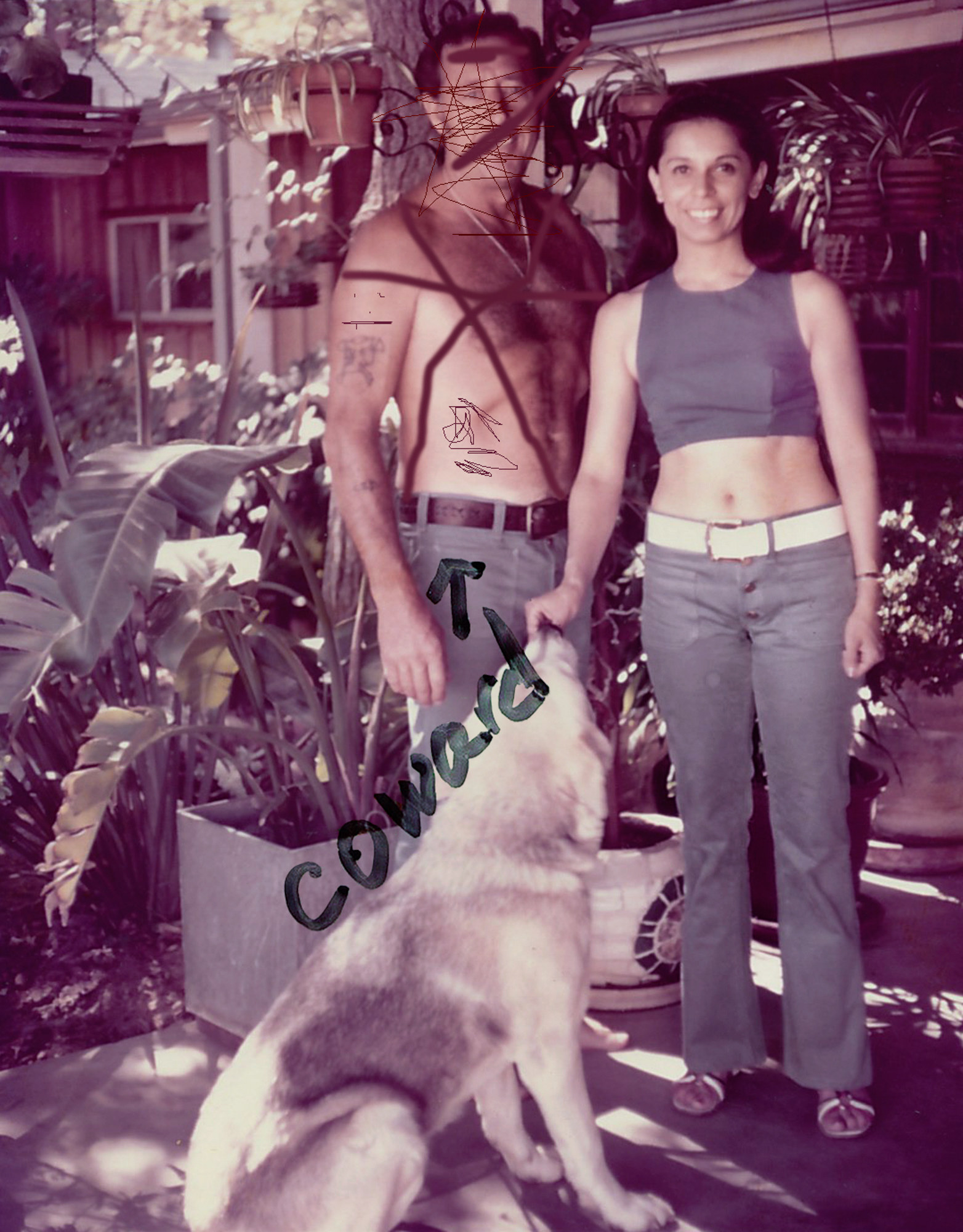

Hannah Kozak's mother left her father when she was 9, having fallen in love with another man who turned out to be violent. As a result of the abuse, which Hannah witnessed for five years of her childhood, her mother was left with brain damage and partial paralysis at the age of 35. Kozak, now an LA-based photographer, explores the decadelong process of rebuilding her relationship with her mother in an eloquent new book, He Threw the Last Punch Too Hard.

As the coronavirus pandemic continues and families are locked down together in close quarters, there is a silent and growing crisis of intimate partner violence around the world. This story is a tender and crucial look at the long-term effects of familial violence, and the enduring redemptive power of love and forgiveness. Kozak's images of her mother highlight her individuality and perspective on the world, with her past and her present delicately interwoven. BuzzFeed News spoke with Kozak about her work and how she approached working with her family on such a sensitive topic.

How did you decide to turn what would maybe be considered a "personal matter" into a book? Why is it important that it is visible?

I didn’t decide. My soul gave me no choice. I listened to my feelings. Getting to the bottom of things is part of who I am. I used to think my private life was no one’s business and that what happened to my mother was my secret to bear. But on my spiritual path, I learned to stop hiding from my past and pain. Diane Arbus said, “The more specific you are, the more universal you’ll be.” If I’m going to bear my soul, may as well reach as many as possible. The Talmud says if we save one life, we save the world. Why a book? I feel there is nothing more permanent than a book. A photography exhibition goes up, and then it comes down but a book lives on. Books were my first love, photography my second, so combining them was the perfect answer to sharing my mother’s story.

When I started to make my photographs of my mother, I wasn’t planning to show them to anyone. They were my scrutiny, my exploration of my mother, who was a stranger to me. Initially, photographing my mother became a way for me to connect with her while the camera gave me a safe distance. However, I realized quite early that sharing my mother’s story could help others decide to leave an abusive relationship. I cannot do anything about what happened to my mother, but I know that part of why I am sharing my mother’s story (and mine) is to help another soul.

We create change by taking action. I took action. I want my photographs to make people stop and question the problems we have in the world and what we can do to provoke and create change. A photograph is best if it makes you feel. At a certain point, I knew I would publish this work into a book and I was not going to stop until I did. I am determined, stubborn. My focus became myopic, in a way. In a nutshell, I went from hurting to healing to helping.

Can you talk about how your relationship with your mom evolved during this project?

I didn’t even know who this woman was when I began this project. Yes, she was my mother but understand that I lost her so many times during my life that she was a stranger to me. I lost her when I was 9 years old and she divorced my father. I lost her again at 14 years old when she went into intensive care with brain damage, and at 20 years old when my father moved her into a facility, I lost her yet again. My earliest mothering experiences were about feelings of loss and abandonment even if my mother didn’t intend to hurt me. This journey of forgiveness took decades because as an adult, I was a child, angry at my mother for leaving. Unfortunately, for my mother, leaving one man for another was hardly emancipation.

It was not until a stunt job where I broke both my feet, after jumping out of a helicopter, onto the tallest building in Los Angeles and was forced to go inside and feel, that I began to understand that I needed to heal my relationship with my mother. Breaking my feet was my spiritual epiphany. I ran from the pain of what happened to my mother, but I learned that leaning into the pain and sorrow was the only way to heal it. You can only run from yourself for so long. That time forced me to go inward, where I made the decision to return to school. I had to hurt so much that something broke inside of me. Thankfully, through graduate work in Spiritual Psychology at University of Santa Monica and work I did with a healer, I was able to dissolve the judgments I carried about my mother and myself and begin to forge a relationship with her by photographing her. I continued to make photos of her for a decade.

Prior to COVID, I would see her two to five times a week. I like spending time with her. She’s completely present as we would watch cats wander through the garden, listen to Spanish music like Julio Iglesias or Ricardo Montaner, listen to the sound of the water fountains flowing, and sometimes we just sit in silence together, enjoying each other’s company. Since COVID, I have been active in advocating for visitation and was able to see my mother two times per week, through a fence.

One day last week, I had brought her an avocado. She won’t ask for anything, but if I ask “Would you like an avocado?” she always says yes. Alejandro Fernández music playing from my iPhone, a dozen orange roses next to her, a perfect California dreaming kind of day, and she looked at me, sitting in her wheelchair and said, “I have everything.” I think that sums up our relationship and my mother’s ability to be in gratitude.

What did your mom think about this work? How did you approach photographing her?

My father gave me his Kodak Brownie camera when I was 10 years old. As I photographed my mother, she understood that is what I do: make photographs. She never questioned me and my cameras again. I approached photographing her the way I do with everyone: with my heart. Many times over the decade I asked her if it would be OK to share her story in a book, and she said yes. My book was shipped during the summer, and by the time it arrived, she was in COVID lockdown, but as I was given special permission to see her, I showed her the book and she said, “I like it.” That was good enough for me.

Is there one thing that you would want a viewer to understand about intimate partner violence?

After watching my mother’s abuse from the age of 9 until 14 years old, my thoughts are there is not one person on this planet that is worth destroying your life for. I have had men write to me telling me how they watched their father abuse their mother and women write to me in one sentence telling me, “He beat me up again and I cannot see out of my right eye,” and in the next sentence, “I love him so much.” Almost always, the next sentence is “I’m planning to leave.” The process for them to disengage often takes years. What I want them to know is you don’t have years, get out now. Violence in all forms is not love.

Is there one image that you feel strongly about or this project felt to you?

Each image is like a child to me so I feel strongly about them all. But the image of my mother behind the gate, waving to me, still breaks my heart. My mother could be bitter, mean, and angry, instead she chose acceptance. On the days where I am in acceptance, I leave knowing I have brought her joy. On other days, it is still painful to me that my mother’s adult existence has been so challenging for her.

I brought my mother to the hospital when my father was dying. With her good hand, she pulled the blanket covering him onto her lap so the two of them were wrapped up together again, one last time. “Everything was a mistake,” she said out loud to no one specifically. “What?” I said, even though I knew what she was telling me. I wanted to hear her say, “I made a mistake. I should not have left your father. I should not have stayed with that abuse, but I was scared and had nowhere to go.” But she could only say what she did and she repeated it two more times, the first time slowly, as if she was spelling it, and then she screamed it. “It was a mistake.”

This book is not just a sad story of photos of an older woman. It’s a photography/memoir narrative where I explore isolation, loneliness, abuse, connection, compassion, forgiveness, family, humanity, grace, joy, and above all, love. It’s the story of a mother–daughter reconciliation. I could not live with myself if I didn’t give voice to my mother’s story. My scrutiny became this book.

Maybe my father knew I needed a way to express my feelings which is why he gave me his camera. His intuition, in part, is how he survived eight Nazi forced labor camps. I didn’t have a voice as a little girl. I do now. It’s the sound of my shutter.

I leave you with this. My mother only said two things that have stayed with me since childhood. “Cleanliness is next to godliness,” which I thought about as I washed my car this morning, after being on a dusty location for five days. “Hannah, get an education” was the second piece of advice I remember. I took note and listened to her. Between the lines, she was telling me not to do what she did and be dependent on anyone but to stand on my own two feet. I listened to my mother.