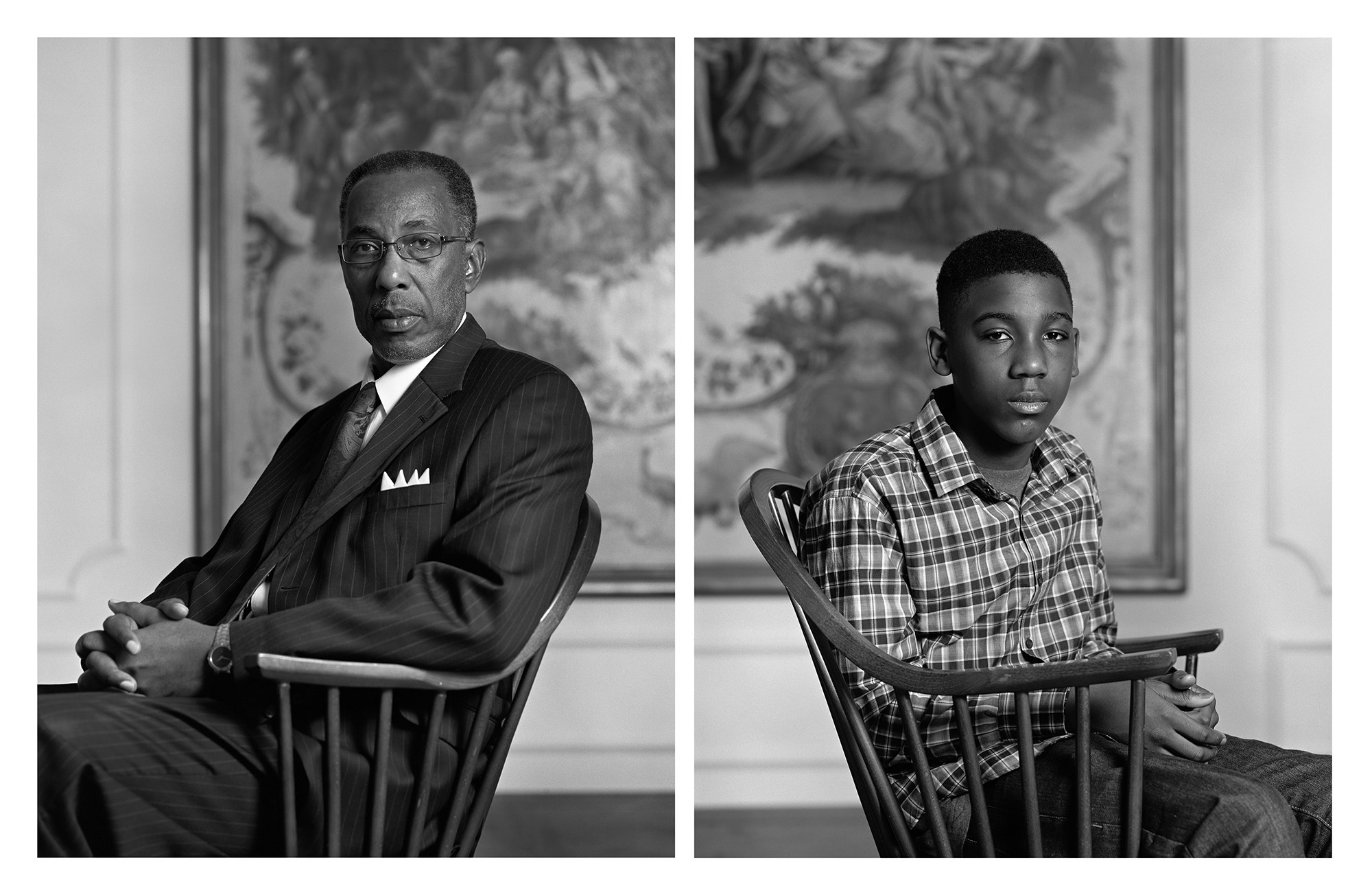

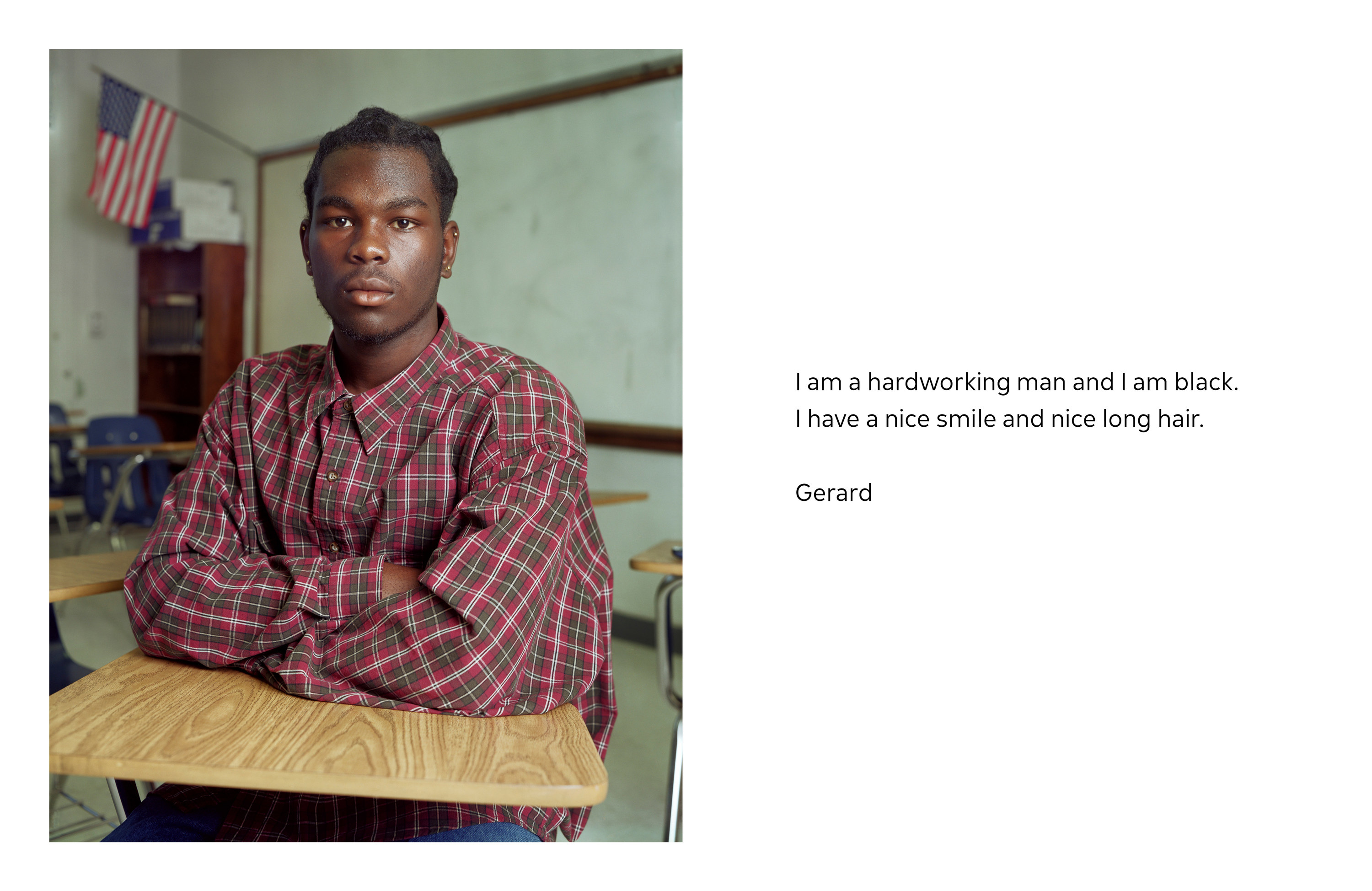

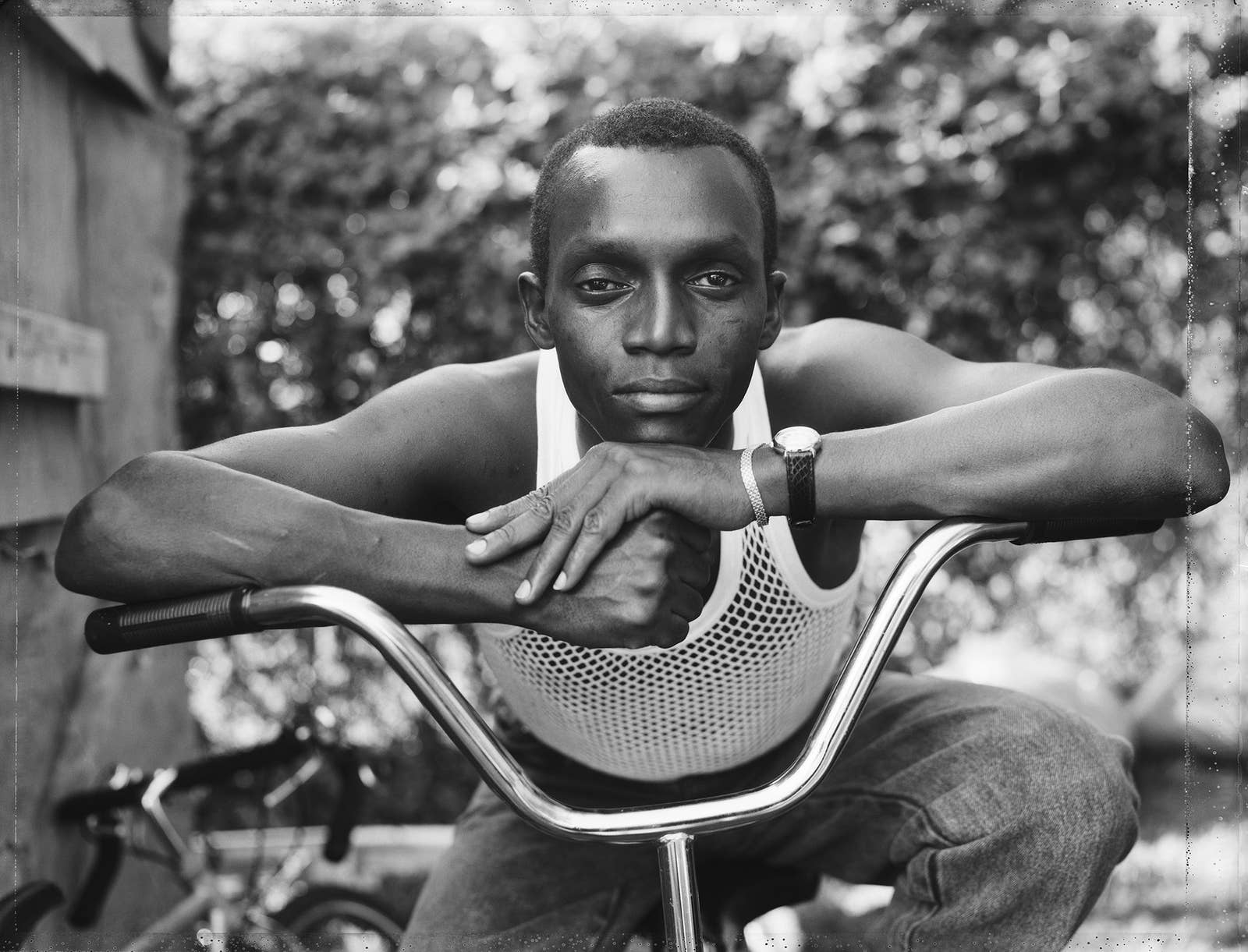

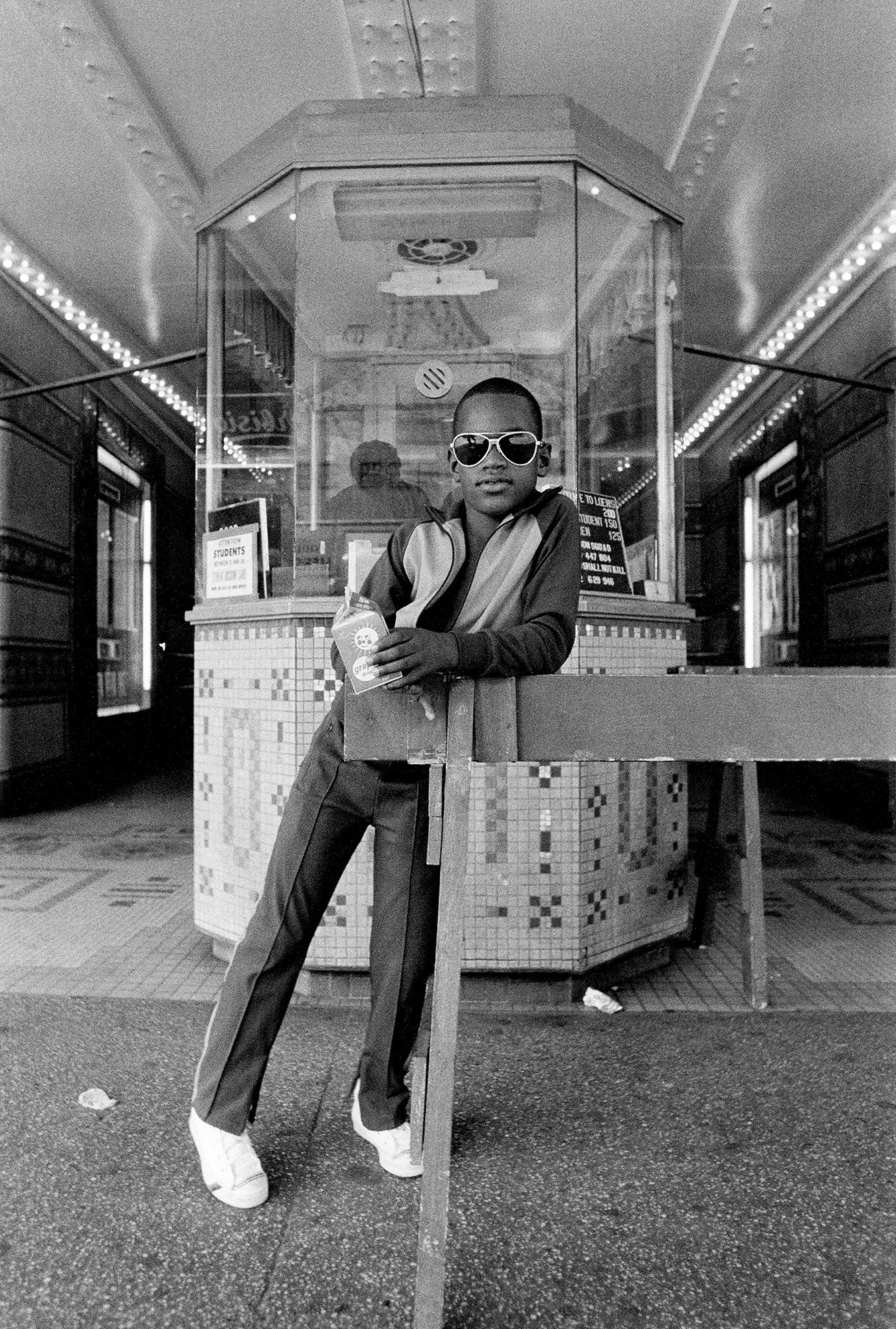

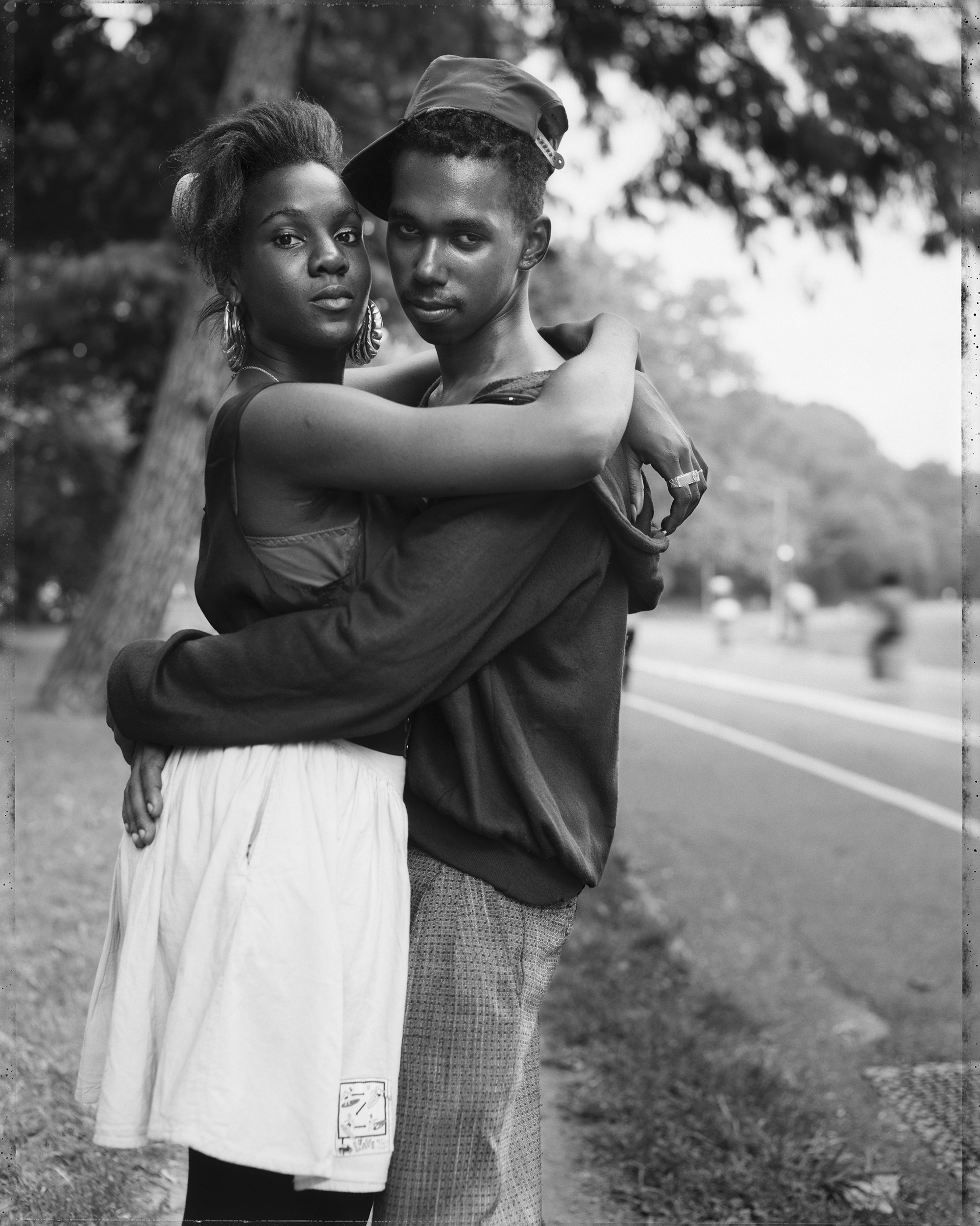

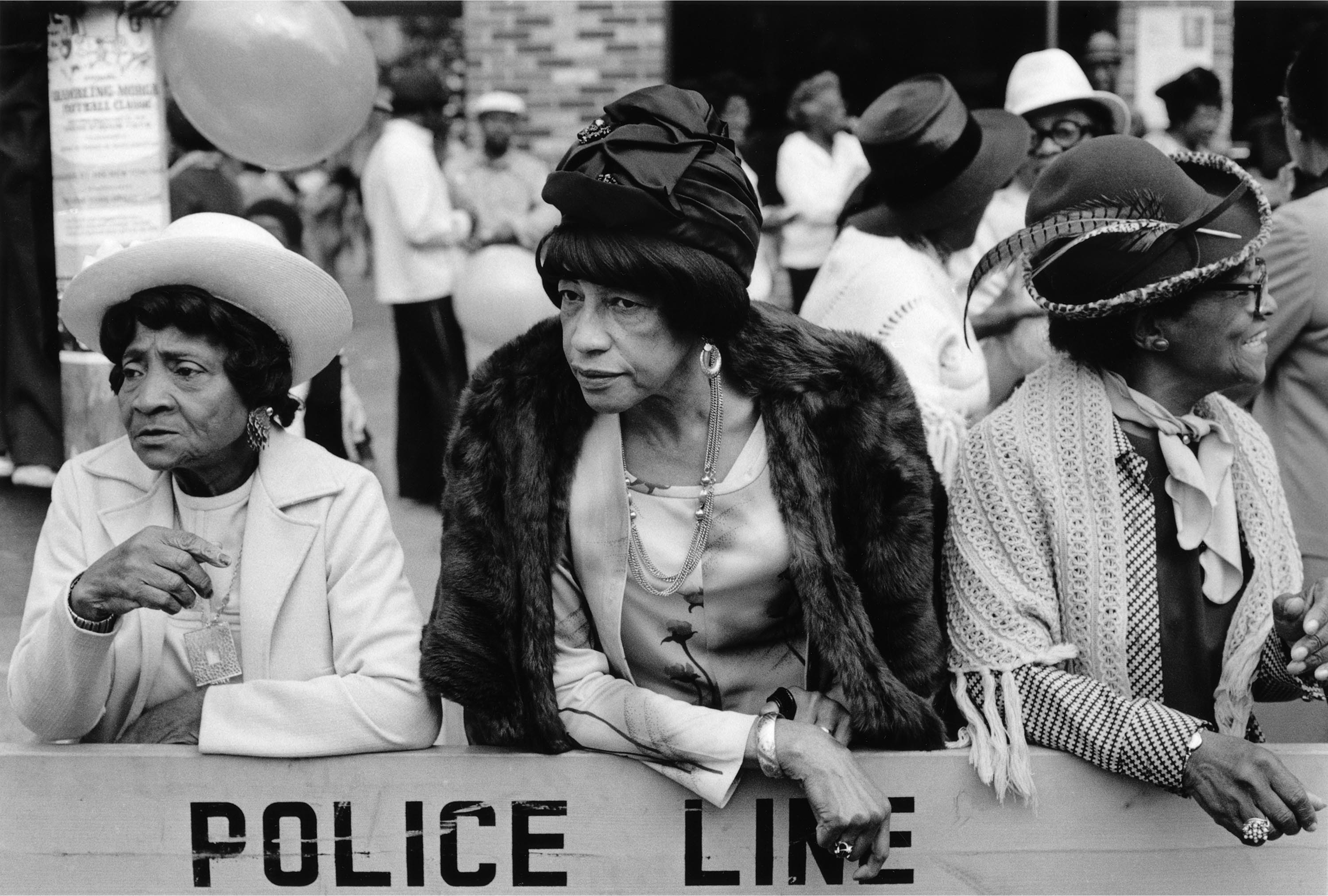

Dawoud Bey is truly a national treasure. His photographs, which primarily highlight the experience of Black Americans, also speak deeply to our shared American history, leaving the viewer with a meditation on the past that is both profound and beautiful.

Now Bey's decadeslong career is being celebrated with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in New York City that feels tailor-made for the current moment, as the US reckons with racism and issues of representation. It is a rarity for a living artist who is still producing work to be given such a big show, but it speaks to the importance and relevance of Bey's vision.

"So much of his work is about contemporary Black life, but also how that experience is fundamentally shaped and defined by the past," said Elisabeth Sherman, the assistant curator at the Whitney who was involved in putting together the Bey exhibition. She cited his early work of street portraits in Harlem and how that evolved into his more recent work, which examines the legacy of the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham, as well as the myth and legacy of the Underground Railroad.

It could feel like a shrewd public relations move on the part of the Whitney to hold his retrospective now, with racial justice being in such public focus and after several recent race-related scandals at the institution itself. However, museum staff say that this show has been in the works for several years, in collaboration with SFMoma.

"This is the work that Dawoud has been doing for 40 years, and this is the work that we committed to exhibiting, because it is always urgent, no matter how much the conversation is on the front page of the news," Sherman said.

Bey has been vocal about the need for more representation within museums and for the spaces themselves to be more accessible to a wider audience. His work was originally inspired by the desire for ordinary Black people to see themselves in art.

He answered questions from BuzzFeed News about his work and what this show means to him now. His photographs are currently on display at the Whitney and will also be exhibited in Houston. A collection of his early portraits in Harlem was released as a book by the publisher Mack earlier this year.

What made you first pick up a camera? Was there a moment when you really fell in love with photography?

I guess I fell in love with photography when I started going out looking at exhibitions at galleries and museums early on in my development, in the early to mid-1970s. I had gotten my first camera from a family member when I was 15, but those exhibitions began to give me a sense of the possibilities for what I might do with the camera as an expressive tool.

You've talked a bit before about how the show Harlem on My Mind at the Met influenced you as a child. Can you talk about what having this retrospective at the Whitney (and at SFMOMA and High Museum) means to you now, especially in light of the past year?

The Harlem on My Mind exhibition, which I saw when I was 16 years old, was the first time I saw pictures of ordinary African Americans inside of a museum. It pretty much set the aspirational goal that I have now realized for some 40-odd years since having the first exhibition of my work at Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979. Being able to have my work placed alongside other works in the Whitney and other museums, and to have my work be a part of the conversation taking place around those objects given serious consideration in the space of the museum, has been an important goal of mine for a long time. It’s been equally as important for both younger Black artists and Black people who visit those spaces to see works made by a Black artist that engages in a complex notion of Black representation.

How would you like to see museums be more accessible to more people?

As museums become more ambitious and expansive architecturally, the price of admission needed to sustain them has become increasingly prohibitive. I would hope that museums would continue to have days and times when admission is free to the public to make that experience a more broadly accessible one, and to broadly publicize those free days so people know that they have access to them regardless of income. I also think museums can continue to do more through their programming to host admission-free programs that tackle issues of interest to the larger social community, and do that with a diverse group of artists, educators, scholars, curators, and others. Museums have an obligation to construct a more inclusive sense of art history through their exhibition and acquisition programming. The current moment calls for an even greater degree of social accountability, and museums need to continue to find ways to collapse the walls between the institution and the broader social community.

Your work straddles a really interesting line between fine art and documentary. Can you talk a bit about how you approached your more recent work, in particular The Birmingham Project and Night Coming Tenderly Black, and how they are different from your earlier work in Harlem?

I’m not a big believer in categories, but my work has always been about my own ideas about the things and people that I have made work about. I’ve never made any pretensions to a kind of documentary objectivity. With the current work, unlike my earlier work, I’m engaging specific moments and places within African American history and reimagining them through work that seeks to make that history resonate, finding different conceptual strategies for bringing that history into a contemporary conversation.

You are one of the best-known Black photographers, and your work deals a lot with the representation and history of Black Americans. How do you want to be remembered?

I hope that I’d be remembered as someone who practiced their craft at the highest level of rigor and made work about things in the world that really mattered.

What's next? Do you have a new project in mind? What are you excited about right now?

I am currently making work on and around the landscape of four different plantations in Louisiana, seeking to visualize those sites where the formative relationship between African Americans and this country begins to unfold. I am making photographs as well as a three-channel video work at these sites. These photographs and the video work will be exhibited in New York in September at Sean Kelly Gallery and at Prospect.5 in New Orleans in October.