For much of the past decade, Kadir van Lohuizen has been using photography to try to document the climate crisis and explore what it means for the future. Since a chance encounter in Panama during a reporting trip, the Dutch photojournalist has been documenting the effects of rising sea levels across the globe. Working closely with scientists, and while learning a lot about both human migration and tides, van Lohuizen has managed to prove visually what so many experts have been warning for years: Our coastlines are in danger.

His work, which spans 11 countries, has been used in presentations for the United Nations and at the Paris climate summit, and has been made into a television series, a book, and several exhibitions. One currently on view at the Museum of the City of New York, Rising Tide, highlights how the island city will be affected by the changes to come.

His book, After the Deluge, offers a comprehensive look at the slow-motion climate shift that is happening on every continent — and how it affects the people who live there. While some countries have proved adept at adopting forward-thinking policies, including relocation strategies, many are refusing to acknowledge rising sea levels as anything more than a regional issue. Van Lohuizen’s work starkly points out the intimate connection between civilization and the sea, challenging the viewer to think more critically about the future.

Did you know that this project would take on so many lives?

I started this back in 2011–2012, as a small story. I was looking into contemporary migration in the Americas, traveling overland for a year from the tip of Chile to the tip of northern Alaska, looking at why people were migrating.

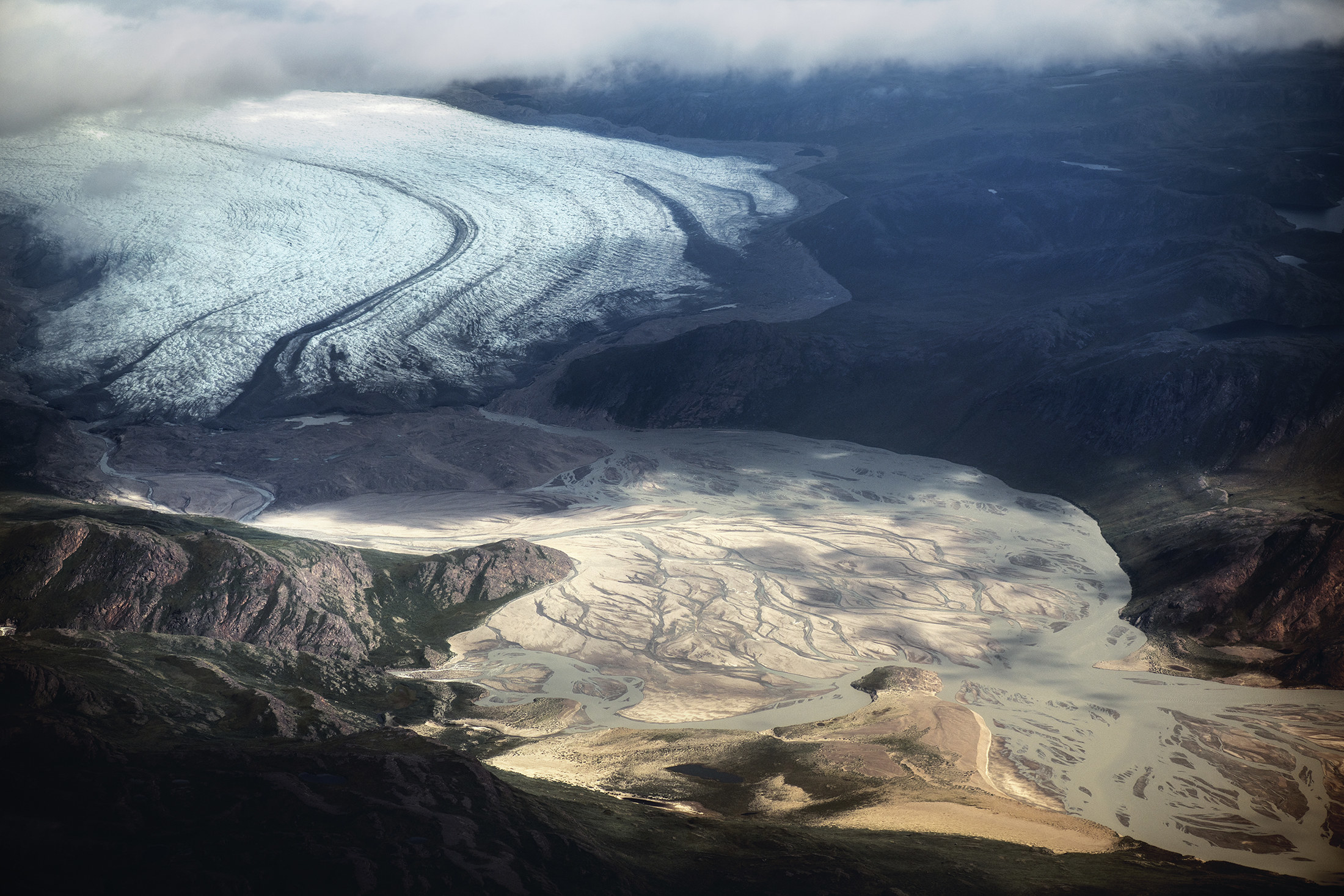

As I was interviewing people on the San Blas Islands in Panama, they said to me, “We are being evacuated because the sea level is rising.” I was a bit puzzled because, you know, I’m talking to them from the bottom of the sea, like six feet below sea level. This was 10 years ago, and I knew that sea level rise was an issue that would be coming up, but I didn’t realize that this was an issue already. I started to research different regions in the world, if there was an urgency elsewhere as well. The big challenge was, how do you visualize something which is not visible yet?

So how do you get this into a strong image that people will understand?

It entailed quite a bit of research, because I wanted to find regions beyond where people might realize this is an issue already, like in the nations of the Pacific or Bangladesh. I really wanted to touch upon this globally.

I actually thought that I was closing the project back in 2015, because it felt like I was starting to repeat myself. How many islands, or how many eroded coastlines, can you show? It was a collaboration initially with the New York Times, and then it became an exhibition, which traveled and went to the climate summit in Paris, and eventually I was approached by Dutch public television. That allowed me to return to some of the places I’ve been, and I sometimes found the same people.

I worked a lot with scientists. I definitely had to adapt my working methods very early in the story, because you know, normally, as a photographer, you work with the light. I very quickly discovered that, if I wanted to visualize it, that I had to work with tides. If you see that land already floods when it’s high tide, it makes it a little less hard to imagine what it would mean if the sea permanently comes up three feet or six feet. It’s not a lot. And it’s not a question if the sea level is rising. It’s the question of when.

When do people decide to relocate?

You would assume that the issue really becomes urgent when the water is permanently in your house, but it starts much earlier. If the sea water floods the land, and then often doesn’t recede, people can’t grow crops anymore, because the soil gets salinated and the drinking water gets brackish. That’s enough of a reason to relocate. Often this is not coordinated by the government, but it’s people themselves who will make this decision.

And where are people relocating to? Are they going to cities? Are they going to other countries?

It depends where you are, right? If you’re in the island states in the Pacific, like the Marshall Islands or Kiribati, there’s nowhere to go, because it’s not more than three or five feet above sea level. Not only do people not know where to relocate to, but they don’t know where they will have the country to relocate to.

If you have to relocate, you are becoming, in fact, a climate refugee, especially if you have to cross the border. And that’s just not addressed internationally, which is kind of crazy. If you are trying to get asylum somewhere for climate reasons, there’s zero chance that it will be granted to you. This is usually considered a national or local problem. So Bangladesh has an issue and the Netherlands has an issue, but it’s not addressed internationally.

The rising sea levels are an aspect of the climate crisis, but obviously, it’s much broader. I don’t know to what extent it is discussed in the US, but a lot of people are fleeing Central America because there’s no water anymore, or they can’t grow crops anymore, they’re losing their lands.

By the way, these people on these islands in Panama are still there. It was the government’s program to be relocated, and that money disappeared suddenly. They are Indigenous, and they don’t have the highest priority in the Panamanian government. So that was interesting to see.

I’ve noticed that initially, when I was there, people were telling me that they were relocating and that they were reluctant to do it, which is obvious, right? It’s a very hard message to anyone, if you are told that you have to leave the land of your forefathers: Drop your life, go to higher ground where you have to learn to become a farmer, where you’re always a fisherman. When I came back [later], it seemed very complicated. People were kind of anxious to leave then, because they felt it was becoming too dangerous.

You’d been working a lot with conflict and migrations and these really complex social issues over the years. Is that very different from covering the climate crisis?

I think they are becoming the same. We know that one of the main reasons for the Syrian conflict was initially, water shortages. If you see what’s happening in the Sahel, and elsewhere, it is often related to the climate crisis. And then if al-Qaeda or ISIS or whoever steps in, it kind of changes the story, but they are so often related to each other.

Through the course of this project, did you see solutions or strategies being enacted, where you thought, OK, maybe we’ve passed this tipping point, but maybe it’s not all lost?

I hope I have been able to give some kind of a balanced view. Many people ask me, it must have been very depressing in Bangladesh, and you know, it’s actually not, because people are taking solutions into their own hands. They’ve been living with the water for their whole life. They know what happens, and they adapt. I met lots of people who moved already five or nine times. And then, if it’s not sustainable anymore where they are, they will move to the big cities. There’s resiliency.

There is nothing new about rising sea levels. The big difference is that it used to take hundreds of years, or if not thousands of years, and now it’s happening in two generations. That makes it very different.

Before the Dutch were so well-protected by dikes, people would just build hills in the land to make sure that their home was dry, or they would move to another area. Especially in Western countries, we’ve lost our ability to adapt. We consider a city like New York or Miami or Amsterdam, that it has to remain where it is. And obviously, we are dealing with a much larger population now.

The Delta Commissioner in the Netherlands asked one of the big engineering companies back in 2018 to look at the worst-case scenario. And that worst-case scenario, basically, is if nothing is done, and if we don’t reach the reduction of the global temperatures in the Paris Agreement, the sea level could rise in the Netherlands anywhere between three and nine feet by the end of the century.

That’s 80 years. If you’re born today, that’s something you’re probably gonna witness. We in the Netherlands can maybe deal with three feet, but we cannot deal with six feet or nine feet. So there are very wild plans about what the Netherlands should do to protect itself, but it often seems that the most recent realistic plan is relocation.

To imagine that cities like Amsterdam, or Rotterdam, which is the biggest port of Europe, could be abandoned is a very difficult concept.

I think it’s very problematic in New York as well. It wasn’t really until Hurricane Sandy that people even started to consider sea levels and take it seriously, and the investment has still been very slow. We are eight years, nine years after Sandy, and in terms of something real physically happening, there is almost nothing.

A lot can be done, obviously. The Dutch have proved that you can live in a country below sea level, but it’s been a very high investment, and it took centuries to create this, in what’s still a very tiny country.

Most of the US East Coast is unprotected. Even worse, the people who live on barrier islands. Very, very valuable real estate exists on a barrier island, but you should not live on the barrier, because a barrier is supposed to move, to be touched by storms and form a buffer to protect the land.

The time factor is a huge issue. Bangladesh is one of the few countries that has embarked on a huge master plan to protect its coastal regions, which is called Delta Plan 2100. It’s an interesting plan because it’s not only talking about building dikes and protecting the land, it’s also looking at where people might have to relocate, and if they have to relocate, you have to provide them with new livelihoods. It’s very interesting.

I didn’t include in the project the Netherlands initially, because I was looking for regions or countries in the world where there was an urgency, and the streets of Amsterdam don’t get flooded. With the climate crisis, we always think that it’s not going to be as bad as has been predicted, but there’s no single reason why that’s correct, because every scientific report which comes out is actually painting a darker picture.

I often question myself, how is this possible? And an answer to that is maybe that we are in our comfort zone, right? We grew up with the fact that the economy is growing and that your children probably will have a better life than us. We need to make some sacrifices, which none of us like. So, you know, take one or two steps back and compromise to make sure that next generations are still OK, which is a very different difficult concept for us.