A former photojournalist turned artist, Richard Mosse, has used infrared light to explore the long-standing conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and thermal radiation to highlight the journeys of migrants heading to Europe. Mosse is extremely good at using technology in creative ways to highlight complex social issues and his newest work, with multispectral imaging in the Amazon rainforest, is no less haunting.

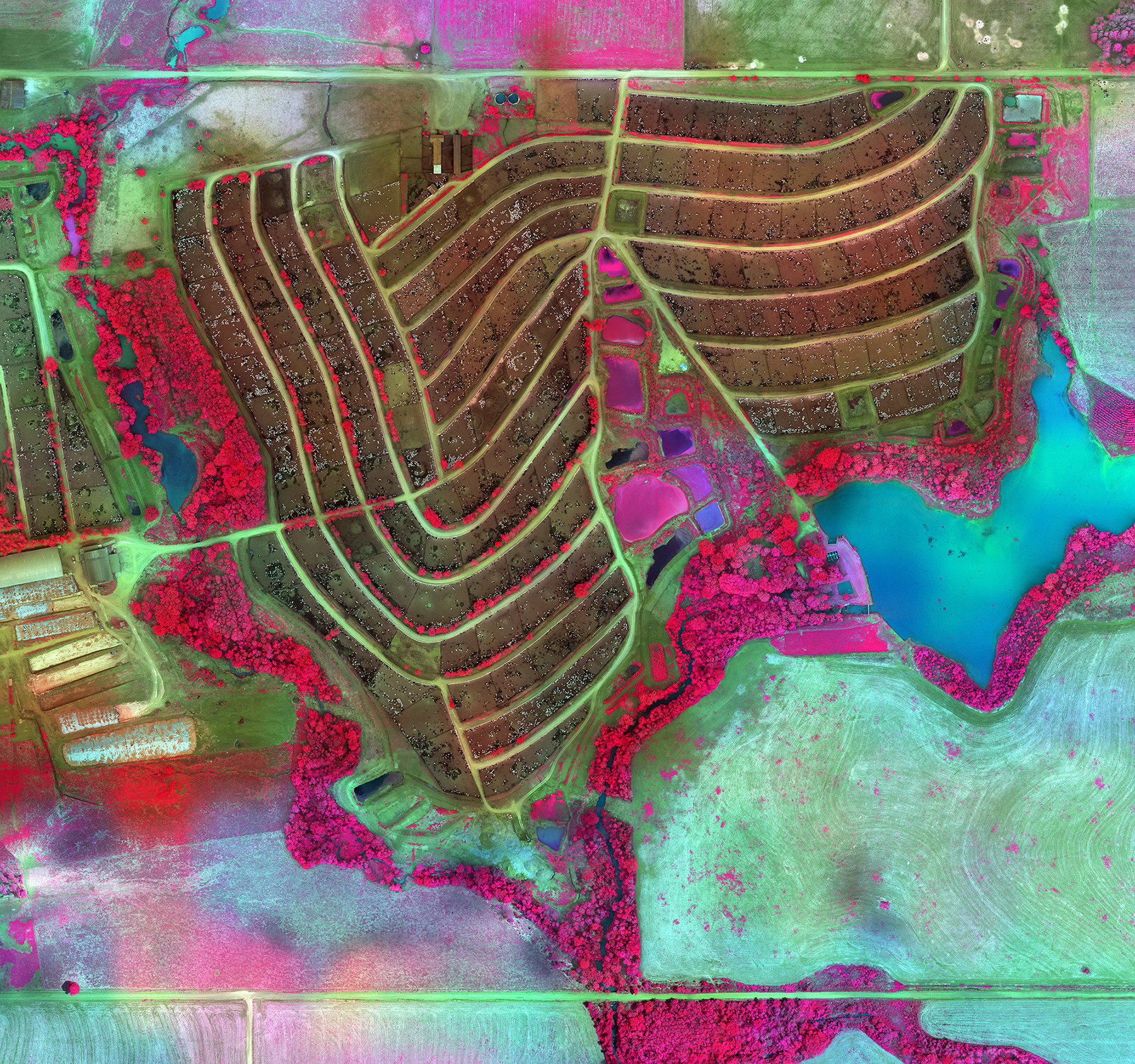

Relying on the same technology that agriculture and forestry businesses use to monitor the area, he creates otherworldly images to publicize the extent of the damage to the Amazon basin. Images of the rainforest burning have been widely seen over the past few years. In an interview with Vice World, Mosse described the area as a war zone. Policies from Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro — including rapid deforestation to expand agribusiness and mining — exacerbated the 2019 wildfires. Mosse's images also show less obvious forms of damage, from pollution to the effects of monocropping, or the practice of repeatedly growing a single crop on the same land.

His work helps us comprehend the multilayered destruction happening right now, even if the numbers attached to the climate crisis and deforestation are hard to fathom. Mosse’s technicolor landscapes are the definition of surreal, and these beautiful images are a warning that we will lose this huge, diverse ecosystem if we're not more careful. BuzzFeed News emailed with Richard Mosse to discuss his process.

How long were you working down in the Amazon? And how did this project come about?

In summer 2019, there was a watershed of reporting on the Amazon rainforest’s deforestation. For a moment, the whole world’s attention was drawn to this unfolding environmental catastrophe. I wanted to try to focus my own lens on it but was immediately struck with the difficulties facing any photographer or storyteller who attempts to convey such vast, atmospheric processes.

In a recent article, Rebecca Solnit writes, “Climate change is invisible, in everyday political consciousness, because it occurs on a scale too vast in time and space to see with the naked eye and because it concerns imperceptible phenomena such as atmospheric composition.” This was really the starting point for me. I’m fascinated by the limits of human language and perception and have tried to engage that problem of visibility by employing camera technologies that see invisible forms of light, which literally and metaphorically “make the invisible visible,” in Solnit’s words.

That was no easy task in the Amazon, where deforestation is occurring on a devastating scale. Almost everywhere I went, the landscape was in a process of being razed for agribusiness and the rivers ravaged by mining and damming. The scale and complexity of these processes unfolding in time and space is extremely difficult to articulate with a modest camera. I struggled to find a suitable tool that allowed me to communicate these urgent environmental narratives in an adequate way.

Deforestation, for example, is a process that takes years. This whole cycle releases huge amounts of carbon dioxide and methane whilst wiping out one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet. This is not easy to show. The rainforest’s destruction occurs all around, across several countries, willfully carried out by millions of people. It’s certainly visible, but processes that occur to the land itself can be very difficult to describe.

In thinking about all this, and struggling to describe it, I discovered that scientists who analyze changes to the environment employ certain remote sensing cameras carried by satellites in space. These special cameras are multisensor arrays that image solar energy reflected from the surface of the Earth below. Each sensor captures a different wavelength or band of reflected light. These bands carry enormous amounts of useful information about the health and stress to the environment.

Meanwhile, I learned, remote sensing multispectral cameras are widely employed in agribusiness and by mining companies to more profitably exploit the environment. So you could say that this camera technology is at the crux of the entire narrative since it’s used by scientists to help us fully understand the scale and impact of the problem while being a tool of agribusiness and mining industries, which are responsible for this systematic destruction. I am fascinated when I find a medium that is, in a way, an agent within the subject I am trying to describe, not least because it is tailor-made to clearly depict changes in the landscape in powerful ways.

The camera that I could afford was a small 10-band multispectral camera designed for agribusiness to help farmers understand which crops are under stress and need attention. This camera was designed for drone use. I attached it to a drone and, with great difficulty, learned to autopilot the camera over sites of environmental crimes across Brazil’s “[Operation] Arc of Fire,” a sort of front line of deforestation and illegal activities that spans thousands of miles from the Pantanal [region] in the west through the states of Mato Grosso, Amazonas, and Pará. According to a recent report by MapBiomas, 99% of deforestation in Brazil results from illegal activities. These crimes happen openly; you pass by huge numbers of them as you drive along. Environmental crime and deforestation in the Amazon have been normalized, and my objective is to highlight and communicate these crimes in order to, in the words of Rebecca Solnit, “make what has long been accepted unacceptable.”

The images combine different bands of multispectral reflectance data to create electric colors; yet, articulated over such highly detailed organic landscapes, the resulting images seem very fragile. This work conveys frangible organic matter dominated by extractive violence at the hand of man. They are living maps, showing signs of life, but evoke dieback, tipping points, and ecocide.

Your work is shown in galleries but deals very directly with human crises. What audience are you trying to reach?

Galleries are a blank canvas for an artist’s creative expression. That artist is free to create artwork as political, transgressive, academic, ambitious, opaque, dry, allusive, critical, or as crazy as they wish. You don’t get these freedoms as a photographer working with magazines or newspapers, which have tight deadlines and restrictive orthodoxies in terms of narrative visual language, as well as certain codes. Your work often serves to illustrate a writer’s text, which can be limiting. So I prefer showing my work in art galleries as it allows me to speak freely and, I hope, in powerful new ways.

If the work hits the moment, these conversations can become very important. This all begins with gallery shows, where you’re free to make something entirely new. I know the art market gets a bad rap, but many art collectors I know are very serious about supporting artists that take risks and speak truth in original ways.

What inspires your work?

Throughout my practice, I’ve searched for ways to push the boundaries of documentary forms to revive urgent, global stories that may have been exhausted in conventional news media. I begin with photographic imaging technologies but also take literature as a starting point or build out my ideas with references to a selection of related texts or novels. This project emerges in certain ways from Claude Lévi-Strauss’s masterpiece of anthropological study and travel writing, Tristes Tropiques. My last project, Incoming, was greatly inspired by J.M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, Dino Buzzati’s The Tartar Steppe, and Franz Kafka’s The Castle. And earlier works, Infra and The Enclave, were inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness.

What is the best piece of advice you've received as a photographer?

I guess that would have to be Samuel Beckett’s “Try again, fail again, fail better.” I find my own failures and dead ends very generative as an artist. As a documentary photographer, one great bit of advice comes from the ice hockey player Wayne Gretzky: “You miss every shot you don’t take.”