Greg Berlanti — television's most prolific producer — has methodically and purposefully revolutionized how LGBT people are portrayed in popular culture. Among many other characters he's created or overseen, there was Jack (Kerr Smith) on Dawson's Creek, a gay high schooler who enacted network television's first passionate kiss between men; Dirty Sexy Money's Carmelita, Candis Cayne's transgender character who had an affair with a rich politician (Billy Baldwin); and, currently, Chyler Leigh's Alex Danvers, a kick-ass lesbian secret agent who happens to be Supergirl's sister. Berlanti, 45, who grew up in a New York City suburb, went to Northwestern University, and was eventually hired by Kevin Williamson to work on Dawson's Creek, has not been able to pioneer representation in the same way for film.

Not yet, anyway.

Berlanti's third movie as a director, Love, Simon, comes out March 16 on 2,400 screens in the United States. Based on Becky Albertelli's 2015 young adult novel, Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, and released by Fox, Love, Simon is the first movie produced by a major studio about a gay teenager — a despairing truth that is only ameliorated by the barrier being broken now. If Love, Simon makes money — and with a budget of $17 million, it is poised to — there will surely be more to come.

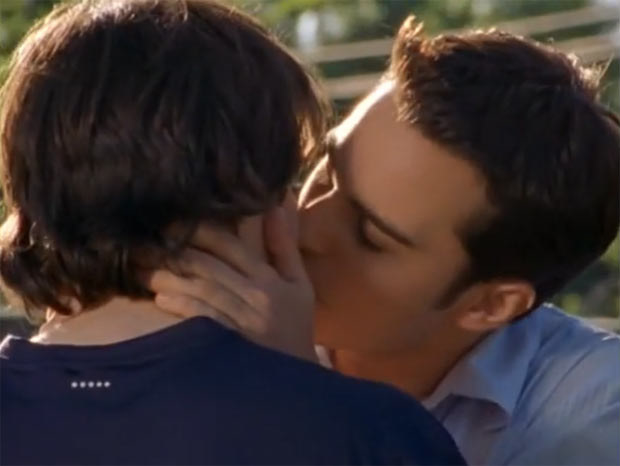

In the movie, Simon Spier (Nick Robinson) is a closeted high school kid who begins an email romance with a classmate called "Blue," who has anonymously come out on the school's gossip site (Simon signs his emails with the name "Jacques"). When he forgets to sign out of his Gmail in the library one day, a fellow classmate, Martin (Logan Miller), blackmails Simon into helping him get a date with Abby (Alexandra Shipp), one of Simon's best friends. Along the way, Simon betrays his friends, lies to his parents, and falls in love with Blue (despite not knowing who he is), all while worrying about being outed. But Love, Simon is not Heathers; everyone, including blackmailer Martin, is pretty nice, and Simon will get his happy ending.

TV, though, is what takes up most of Berlanti's time. He has 11 shows currently (Arrow, The Flash, Legends of Tomorrow, Supergirl, Black Lightning, Blindspot, Deception, Riverdale) or soon to be (You, Titans, Sabrina) on the air, along with four pilots his company, Berlanti Productions, is producing. He also has a husband, the former soccer player Robbie Rogers, and their 2-year-old son, Caleb. Between these professional and personal commitments, the question is always: How does Berlanti get anything done at all? In an interview with BuzzFeed News at his office on the Warner Bros. lot, Berlanti, someone who’s been famously busy for years, waves off the perception that he works 24 hours a day. "I can't say this enough," he said. "People who do multiple things, if they're claiming to do it all themselves, they're lying."

Berlanti is reluctant to talk about which shows get the bulk of his attention, because they're often ones that need his help. "Sometimes I'm hesitant to say the shows I'm working on more, because I don't want to be, like, 'Oh, there are problems on this show!'" he said. Certainly he has had to become more actively involved in running The Flash and Supergirl after a Variety investigation exposed multiple sexual harassment allegations against executive producer Andrew Kreisberg, who was suspended and then fired by Warner Bros. Berlanti has said he did not know about Kreisberg, and has now instituted a number of changes at his company to ensure such things don't happen again. He's hired a head of production, Karyn Smith-Forge, to oversee Berlanti Productions shows on a closer level; instituted yearly performance reviews that will include anonymous feedback for top-level executives; and has begun conducting exit interviews with fired staffers.

Adapting to change is not new for Berlanti. A few years ago, he instituted a target that half of the directors of the company's superhero shows should be women or people of color, a particularly ambitious objective for genre television. Berlanti said, "We committed to ourselves — before there was a movement, and before people were doing it — let's build our own list." The final tallies aren't yet in for this year's five superhero shows, but he thinks they've met, or are close to, the 50% goal. And the company's four pilots are being directed by women or directors of color.

Before Berlanti was a mogul, he was a wunderkind; he was the youngest showrunner in the history of network television when he oversaw Dawson's Creek at age 27. Now that he's older, he said he loves to help young writers develop television. "I have all this knowledge I've accumulated, and experience," he said. "And I'm still passionate about broadcast in a way that I think some of my contemporaries aren't necessarily." In other words, don't expect Berlanti to make an overall deal with Netflix in the way Shonda Rhimes and Ryan Murphy have. According to Berlanti, the streaming-service-that-is-eating-the-entertainment-industry has not tried to poach him, and he considers Warner Bros. to be "a big part of the reason why we're successful."

In a 20-year television career, Berlanti has been prolific — practically libertine! — in his creations. But Love, Simon is only the third movie he's directed, and with the pressure of being the first major studio film about a teen gay romance, Berlanti was attentive to LGBT representation and how it’s changed over time, the casting, and more.

How Berlanti fell for Love, Simon

Berlanti estimates that "every four or five years" he looks for his next passion project — something that feels "like falling in love with somebody." It can be a TV show he creates himself, or, as in the case of Love, Simon, a film to direct.

He had first heard about Albertelli's novel through his own company. Executives at Berlanti Productions had tried to buy the rights, but lost out to Temple Hill, a production company with an impressive track record of YA film adaptations (the Twilight novels, the Maze Runner series, and The Fault in Our Stars). Temple Hill's Wyck Godfrey and Marty Bowen — the eventual producers of Love, Simon — hired This Is Us writers Elizabeth Berger and Isaac Aptaker to adapt the screenplay.

Berlanti read their script in one sitting on a Saturday in summer 2016. "I felt like I really had to be a part of it," he said. "I just had that thing go off in me." He met with Temple Hill and Fox executives to discuss directing it, and found himself volunteering to be a part of the movie in any way they might need. Before he was onboard, according to Berlanti, there were only straight people working on it.

That a major studio has never produced a film about a gay teenager is an unqualified, inarguable fact, regardless of any takes that such a thing is no longer an important milestone. That Love, Simon would be aimed at a teen audience — and not the adult moviegoers that Call Me by Your Name and Moonlight sought — will be another first. But Fox's executives — Elizabeth Gabler at Fox 2000, and Stacey Snider, the chair and CEO of 20th Century Fox — were determined to make it, despite any risk. "We're making this," he remembered they said to him. "The world needs this. We don't need a star. This is what's happening."

Berlanti was in. And Love, Simon was set to shoot in Atlanta in March and April of last year.

Casting the movie had a few bumps

Berlanti needed his Simon Spier, an upper-middle-class, suburban, high school senior who is ordinary in every way except for the secret he is keeping from his friends and family. The part requires someone who can play both comedy and drama. "Your lead creates that tone," Berlanti said. "A movie can only be as funny as they are, or as heartfelt as they can be, or as emotive as they can be." He paused. "And in a young actor, that can be hard to find."

Nick Robinson costarred in the 2015 blockbuster Jurassic World, but it was the 2013 indie movie Kings of Summer that made Berlanti think Robinson could play Simon. "Oh, he seems like he has a secret," Berlanti remembered thinking about him in that movie. "He breaks your heart in that."

Berlanti, the producers, and the studio all wanted Robinson for the role — but then the actor expressed doubts. As Berlanti talked to Robinson about his questions, he kept thinking it would come up that the young actor was worried about playing a gay character. "I've definitely encountered that in my career," Berlanti said. "And it wasn't that. He actually was more curious, being the lead in the center of a movie like this — are you, Greg Berlanti, capable of pulling it off? He didn't say it that way! Because he's so sweet. But he intimated it." Robinson quizzed Berlanti about what tone Love, Simon would have and which movies he wanted it to emulate. "I welcomed the conversation," he said.

Berlanti continued: "After the fact and since, he's told me that there've been times when maybe he was scared about that. But he didn't bring it up to me; he never evidenced that. And I thought, Good for him. He was asking hard questions, like, 'How are you going to cast this thing?' He knew he was going to end up in the center of a poster at the Arclight. And it was really important to him to get it right."

Once Robinson was officially hired, Berlanti cast the other roles: Simon's close friends, Leah (Katherine Langford), Abby (Shipp), and Nick (Jorge Lendeborg Jr.); his potential love interests (Miles Heizer, Keiynan Lonsdale, and Joey Pollari); and his parents (Josh Duhamel and Jennifer Garner). Robinson did "chemistry reads" with most of the cast to make sure their dynamic worked well. Berlanti had heard from people behind Netflix's 13 Reasons Why, which hadn't aired yet, that he needed to audition Langford for Leah, Simon's best friend who is secretly in love with him. "And she won it in the room," Berlanti said. For the role of Nick, who is written as white and Jewish in the book, Berlanti cast the Dominican-born Lendeborg Jr., a colorblind practice he has regularly employed on his shows (most notably with Mehcad Brooks as Jimmy Olsen on Supergirl). "It was so apparent Jorge was Nick," Berlanti said. "I'm only going from my personal experience, but let's say I'm a closeted gay guy, and I want a jocky friend — that friend who doesn't even notice I might be gay, he's so affable and sweet."

The core group of kids rehearsed for two weeks together, which Berlanti — who has worked with young actors since his Dawson's Creek beginnings — has learned is crucial to their process. "It's a safe place for them to try a bunch of things," Berlanti said. "But the secret is, they actually get really close during that time. There's things you can't direct — they'll, like, lean on each other, and they'll kid with each other. Then you just try to capture that part of it."

Casting Simon's parents was also crucial. In the film, they're lovely, and loving, so what is he worried about? Exactly that, it turns out, in Simon's anxious logic. "The notion that he had this perfect family and this ideal thing that he didn't want to upset actually played into the vibe of what we wanted," Berlanti said. And unlike certain parent roles in teen movies or TV shows, they're not extraneous: They're pivotal to understanding what's at stake for Simon, and what he might lose.

Berlanti had directed Duhamel in 2010's romantic comedy Life as We Know It, so it was as easy as calling him to say, "I want you to play the dad." Casting Garner was more of a challenge. She wanted to do the movie, and wanted to be in it "for the right reasons," she told Berlanti. But she had problems with her character's big scene with Simon; it's "not specific enough," she told him, and "she was absolutely right."

Berlanti got together with the writers and producers, and told them his own coming-out story. "The two things I needed to hear and didn't even realize I needed were so simple: 'I still love you' and 'You deserve love.' And 'I still love you' is dad," Berlanti said.

So they crafted a scene for mom — one distinct from Simon's conversation with his father — that demonstrates the "You deserve love" sentiment that Simon needs in order to go forward. "She's propelling him into the whole third act, really, telling him, Go get your happy ending."

The larger meaning of Love, Simon

Berlanti's first movie, The Broken Hearts Club: A Romantic Comedy, was released in 2000. It's about a group of twentysomething friends who live in Los Angeles, and are gay. It was financed by Sony's Screen Gems division with the intention to release it across the country in multiplexes. But even after the movie was well-reviewed at Sundance, Sony changed its mind about the wide release, and switched The Broken Hearts Club to the company's boutique division, Sony Pictures Classics. "I didn't talk a lot about it then," Berlanti said. But it's an experience that's been on his mind during the process of making Love, Simon. "People are used to seeing this in certain places. They're used to seeing it in an arthouse cinema, they're used to seeing it on their television sets," Berlanti said.

In 2018, same-sex marriage is legal, and LGBT civil rights have leapt forward in ways that were unimaginable in 2000, in no small part due to barriers broken on television shows Berlanti himself has produced. Yet "with mainstream features," he said, a romantic comedy featuring a same-sex love story — particularly one aimed at teenagers — is "the last frontier as an audience member."

"It took me however many years from then to now, to actually cross that threshold," he said. "To actually have a lead gay character in a major studio film that actually is going to be on more than 300 screens." It's meaningful to him — and surely will be to queer members of the audience — since LGBT moviegoers who enjoy mainstream films are used to having to read subtexts rather than seeing their own stories on screen. Not here, though. "You don't have to do this extra math in your head, like, Maybe this character's gay," Berlanti said.

Of course, Simon's experience as a white, college-bound, monied teenager with loving parents is specific, which Berlanti is well-aware of as a writer who's created LGBT characters for nearly 20 years. In an October 2000 story in Variety about Jack on Dawson's Creek's groundbreaking same-sex kiss, Berlanti said: "I want the day to come where people don't expect Jack to be every single gay teen. Then I know we've leveled out."

We clearly have not leveled out. Love, Simon takes steps toward intersectionality through the screenplay's addition of the character of Ethan (who is not in the novel, and is played by Clark Moore), an unabashedly out, black schoolmate of Simon's, who dunks on the bullies who taunt him as a routine part of his day. Creating Ethan is still not enough, of course — one studio movie can't make up for Hollywood's history of exclusion.

"I wish that we weren't the first in that regard — I think that comes with other burdens," Berlanti said. "You're not going to be all things to all people, or you're nothing to no one. It's not going to be everyone's experience. The burden that I felt personally is I just want to make it easier for the next people."

So what will be next for LGBT audiences?

Change has come slowly to mainstream Hollywood. A generation ago, it was hard to cast straight actors in gay roles in film, as BuzzFeed News' in-depth story about the 1982 movie Making Love revealed — because it endangered their careers. As Berlanti's Broken Hearts Club demonstrated that stigma has seemingly gone away. (Timothy Olyphant, Zach Braff, Justin Theroux, and Dean Cain costarred in it without suffering repercussions.) The current conversation is more about casting LGBT actors in LGBT roles — an issue Berlanti has thought about quite a bit.

"You're trying to cast the best actor for the part, and that's usually hard enough," he said. "Then there's the element of, as a DGA member, I'm not going to ask someone their sexuality when they walk in the room. So if they're not out on the internet, they may just be a private person. Then there's people you know — but the world doesn't know!"

Over the course of his career, during which he has been out the entire time, a number of actors have sought his advice about whether they should come out. "And I'll say, 'Well, I think what Harvey Milk said is true, that every gay person has to come out," Berlanti said. "But, I also think you have to come out when it's right for you, and you feel comfortable and ready to do that.'"

He called the LGBT actors discussion "healthy," but added, "I don't think you can look at it just through one lens." He also noted an improvement — casting gay actors in straight roles. "Executives or agents or managers would say things, like, 'That person plays soft.' And I wanted to say to them, but I was too young at the time, like, 'You're saying they seem gay. Why couldn't someone who seems gay play this role?'" he said. "And it went away! No one says those things anymore."

Will there ever be a mainstream movie for LGBT moviegoers that's the equivalent of what Black Panther has meant for black audiences or what Wonder Woman symbolizes for women and girls? A big-budget movie in which an LGBT character's identity is pivotal to the plot, and actually helps fuel its blockbuster status?

"Absolutely," Berlanti said with confidence. He pointed to the near-impossibility of getting WB executives to agree to air Dawson's Creek’s same-sex kiss in 2000, and then only a few years later the ease of dealing with the same issues with Kevin (Matthew Rhys) on Berlanti's ABC drama Brothers & Sisters, which premiered in 2006. Then, the same types of executives would give notes like, "Wouldn't the characters kiss here?" Berlanti recalled. "Well, yeah," he would respond. "Are you OK with that?'"

The industry, Berlanti thinks, will continue to evolve as younger people rise in the ranks. "It's never a very long time from when they're assistants to when they're running the business," he said with a laugh.

Fox tested Love, Simon for audiences, as it does all of its movies. And during the LA screening, the kids "cheered when the happy moment happens at the end," Berlanti said, avoiding spoilers. But would the same moment play in, say, Kansas, the filmmakers and studio wondered? So they took it to Olathe, Kansas, to a theater next to a church supply center. "And we got to the moment when the kiss happens — and the applause happened, and it was rapturous. And I started crying," Berlanti said, welling up from the memory. In the discussion group after, they watched a 14-year-old come out to his father. "This kid started talking about his experience," Berlanti said. "And then he ran up to all of us before we got on the van to go back, and said, 'Thank you.' This generation — as, hopefully, we were to the generation before us — they're going to be so much better in so many different, cool ways. ... It can be cloying to say, Oh, children are the answer. But it can also be the truth."