CARACAS, Venezuela — The order was simple: on election day, choose Chavez’s eyes.

The message was literal, as well as metaphorical: the ruling Chavista party is represented by a picture of former president Hugo Chávez on the ballot screen, showing how much he still towers over Venezuelan politics. Leaflets with these instructions covered the ground, pounded by the scorching Caribbean heat, at the final pro-government rally ahead of Sunday’s parliamentary elections.

Thousands of people drank and danced near the makeshift stages strewn along Avenida Bolivár, one of the main thoroughfares here. It looked like a massive office holiday party, with most people wearing shirts emblazoned with state-owned company logos. The campaign slogan, “To the National Assembly, whatever it takes,” blasted from speakers as dozens of plain-clothed security guards with gun barrels sticking out below their shirts stood watch.

The government said it will take to the streets if it loses. So has the opposition.

“This country is very combative,” said Nayauri Jiménez, who works at a public university and danced while she waited for the Chavista rally to start Thursday. “People are willing to give their lives for this project,” she added, facing the National Assembly tower behind the makeshift stage. The same eyes on the leaflets were etched into the top of the building.

Many here agree that these elections could change the course of history in Venezuela. For the first time in 16 years, the opposition coalition, referred to as the Democratic Unity Roundtable, has a very real chance of beating Chávez’s party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela headed by President Nicolás Maduro, and gaining a majority in parliament. The 167 assembly seats, which are the gatekeepers for passing laws and approving budgets, are all up for grabs. Some polls put the opposition at more than 20 points ahead of the ruling party, though analysts say most surveys are not entirely reliable.

“There is a new majority here that knows that it is stronger than weapons, whose conviction is stronger than money,” said Miguel Pizarro, an opposition legislator seeking a second term.

Tensions have been rising for weeks. Regional opposition politician Luis Manuel Díaz was gunned down after a rally in Guárico State, in central Venezuela, a few days after Pizarro was confronted by armed men during a walkabout in a neighborhood here. Opposition leaders and supporters warn that elections may be unfair, a concern bolstered by Maduro’s rejection of international observers from the Organization of American States.

“I come from a dictatorship and I know what this is. This is a 21st century dictatorship”

But despite fears of more sporadic violence on the final stretch, the last day of campaigning went smoothly.

Across town from the pro-government gathering Thursday, the Democratic Unity Roundtable, a coalition of opposition parties, threw its own closing, party-like rally. Supporters filled a single street block — some here blame their significantly lower numbers on the government’s tight controls on mobilization — and the mood was mellow, with people listening intently to the brief speeches. Estrella Goméz and her 11-year-old daughter, Andrea, held hands while listening to a band from the edges of the crowd.

“I come from a dictatorship and I know what this is. This is a 21st century dictatorship,” said Goméz, who moved here from Chile 31 years ago, during the rule of Augusto Pinochet. She said change is inevitable now, with hardships making life unbearable for people here, the most pressing being spiraling violence: there are no official numbers but the Venezuelan Observatory for Violence estimates that nearly 25,000 people were killed last year. Only Honduras has a higher homicide rate in the world, the organization estimates.

Andrea was hesitant to walk the two blocks from her house to the rally because it was getting dark.

Other problems make daily life in Venezuela particularly challenging: a shortage of basic goods means people must stand in hours-long lines to get toilet paper, diapers and milk, among other products, while triple digit inflation makes living off of minimum wage virtually impossible. A mototaxi driver eyed a reporter’s Converse sneakers and said it would take working nearly two 12-hour-day weeks to be able to buy a pair in Caracas.

The government blames shortages on “an economic war” waged by Venezuela’s business community and outside influences, in particular the U.S, to destabilize the country. Several key figures in Maduro’s inner circle, including two relatives, are facing charges in U.S. federal court for drug trafficking-related charges.

Many at Thursday’s pro-government rally said businessmen here hoard goods for weeks, vanishing them from supermarket shelves to make sure they are all sold in a matter of hours when they reappear.

But rather than talk about the hardships enveloping Venezuela, the legislative candidates or even the president, the main focus at the rally was Chávez. If a Martian landed in Venezuela today, it could be forgiven for thinking that Chávez, who died of cancer in 2013, not only remains alive and is running for office but is probably going to win by a landslide.

“Who’s going to win on December 6th?” yelled an entertainer during the event. “Chávez wins!” he responded, his voice barely audible above the pounding music. “Chávez has not left, Chávez is still with me,” a group of women sang in unison near him.

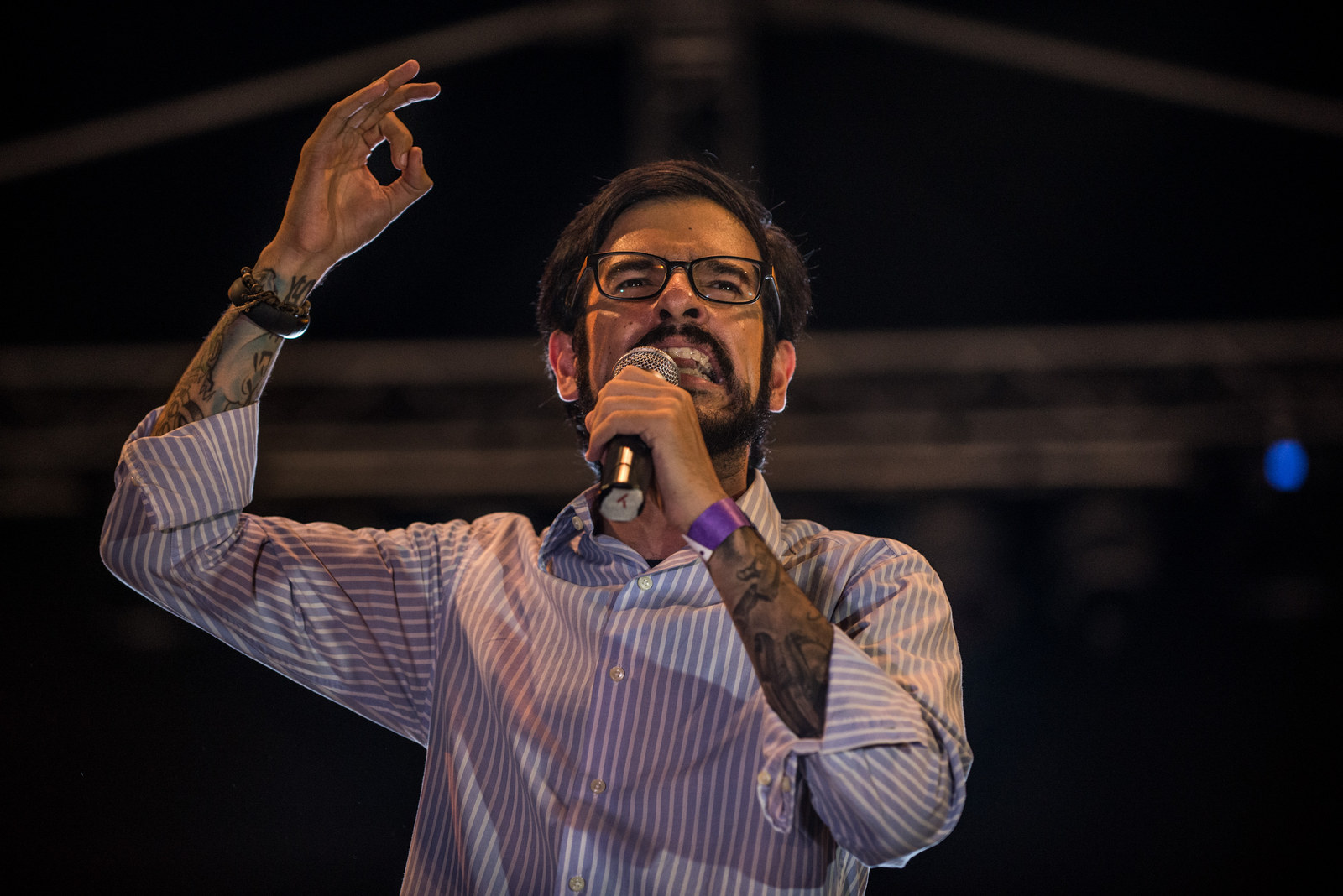

On the opposition stage, the focus was set on the future and the changes to come. “Here, we will all be winners. You are the winners of the fight between David and Goliath. The Goliath of money, of corruption,” said Jesús Chúo Torrealba, head of the opposition coalition.

Venezuelan politics are so polarized they seem simple and absolute on the surface, yet there are infinite shades of gray. Some at the pro-government rally said they oppose Chávez’s hand-picked successor, Maduro. Manuel Urbaez, a 35-year-old telecommunications engineer student, is one of them. Sipping from a juice carton amid the throng of people in red t-shirts, the color of the ruling party, he said he would not reveal who he plans on voting for Sunday but admitted that, “If Chávez were alive, I’d vote for him.”

Urbaez and several others joked that it was their job to be at the rally, quickly clarifying that they were there out of conviction. It is a common practice for the government to bus supporters to their rallies.

José, a 22-year-old who was attending the opposition rally, works at a Caracas tribunal. The government employee stood alone as he waved a large yellow flag from one of the opposition parties. “Many government officials are against the government,” said José, who did not want to reveal his last name because he feared retaliation from his employers.

Still, an opposition majority in parliament does not mean an imminent change in government, or even a more stable political outcome in the long term. First of all, Maduro may seek permission to rule by decree before the new Assembly is inaugurated in January. But even if he doesn’t, there is a possibility that the opposition coalition does not hold together.

Opposition leaders agree on the immediate priorities — freeing political prisoners, resolving the economic and social crisis and changing the government — but are divided by how they want to accomplish them. A hardline faction within the group known as “The Exit” believes change must be precipitated by any means — including through organizing widespread street protests that have frequently turned violent — while others think it must happen gradually and by constitutional means.

“My fear is that when they get to power they will start to fight,” said Alithea Salazar, a 51-year-old travel agent who stood as close to the stage at the opposition rally as possible.

Whoever wins Sunday, protests will likely paralyze parts of Caracas in coming days.

If the opposition takes over the National Assembly, “Our country will fight in the streets, whatever the circumstances may be,” said Maduro in June. “I would be the first one to throw myself out to the streets.”

Freddy Guevara, coordinator of opposition party Voluntad Popular, said they will only lose if the elections are fraudulent, a concern shared by many at the rally. If that is the case, “the people will have to go out to the street to reclaim our rights.”

If people do take to the streets after the election, Salazar says she won’t be one of them. She is tired of fighting, and a loss now would be hard to recover from. “I bought myself a sailboat,” she said with a wink, her head bopping to the beat of the rock band onstage. “If we don’t win, I’ll leave.”