SAN MIGUEL DEL PUERTO, Mexico — Many Mexican children went back to school last week after a bloody summer that saw at least eight people killed and nearly a hundred injured as a four-year-long fight over a sweeping education overhaul turned violent.

Thousands remained without classes to attend, their teachers still away on strike.

A radical offshoot of the teachers union, the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE), has been tussling with the government since 2012 in an effort to quash the reform, which seeks to get rid of ill-prepared educators, all the while tearing apart towns and even families.

The latest upheaval comes as the country begins implementing President Enrique Peña Nieto’s education overhaul program, which introduced a merit-based evaluation for hiring, promoting, and firing teachers. The evaluation system, which does away with the decades-old practice of selling and inheriting teaching positions, is an outrage in the eyes of the CNTE.

Lizbeth Santiago woke up just ahead of the school term three years ago, shortly before the reform was approved, to find herself caught up in the strife currently roiling the region, her life totally changed.

When a group of frustrated parents in San Miguel del Puerto warned the union-affiliated teachers not to go on a strike, they refused. So, the parents locked up the school and then hired new, but ill-prepared, teacher trainees to replace the CNTE teachers. As a result, the CNTE teachers no longer had a school to teach in; when they returned from their protests, they instead set up a makeshift school in the home of one of the teachers.

Since then, Santiago’s hometown has been divided over which school they should be loyal to — the new makeshift school with union teachers who kept abandoning classes to organize strikes or the old school where parents took matters in their hands and hired less-qualified trainees who prioritize classrooms over protests.

Most chose to keep their children in the old school, but some, like Santiago, opted for the new one. Almost overnight, her parents stopped talking to her, her neighbors started dodging her gaze, and her 5-year-old daughter was no longer welcome at kids’ gatherings.

“This is like living in hell,” Santiago told BuzzFeed News.

The schism that pummeled generations-old relationships in this isolated, mountainside hamlet of 2,500 people repeated itself across Oaxaca State over the last three years, putting on display the growing resentment toward the strikes by the CNTE, which ordered many schools closed even as the new school year began.

And yet, the CNTE’s tactics have worked, to some extent. Last week, education authorities announced that evaluations will, through the remainder of 2016, only be required for the 24,000 teachers who performed poorly on last year’s tests. The government planned to evaluate about 150,000 of the country's 1.4 million teachers during its first round of testing last year, though only about 134,000 agreed to take the tests.

The aggressive push by the CNTE to water down the reform has put the government on the defensive, with analysts warning that their protests will further diminish the governing party’s popularity and harm its chances in the next elections.

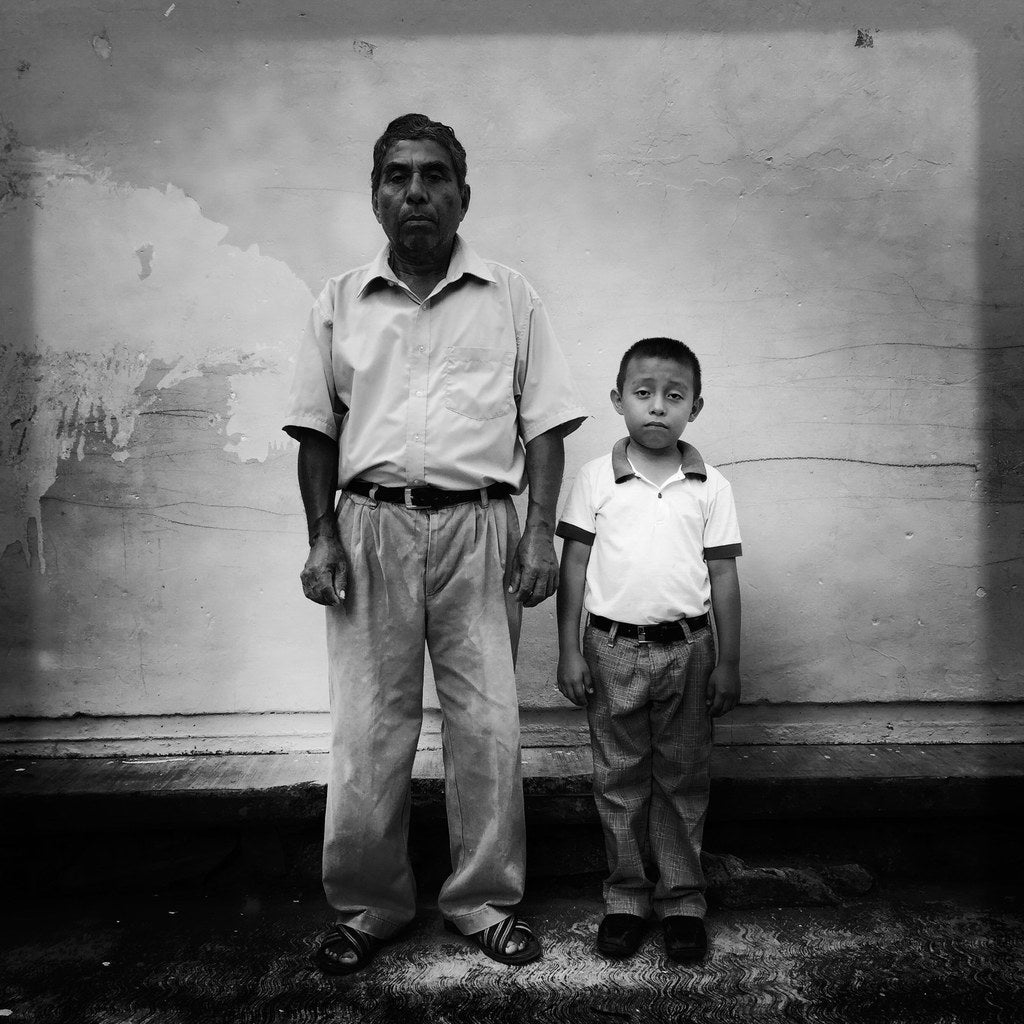

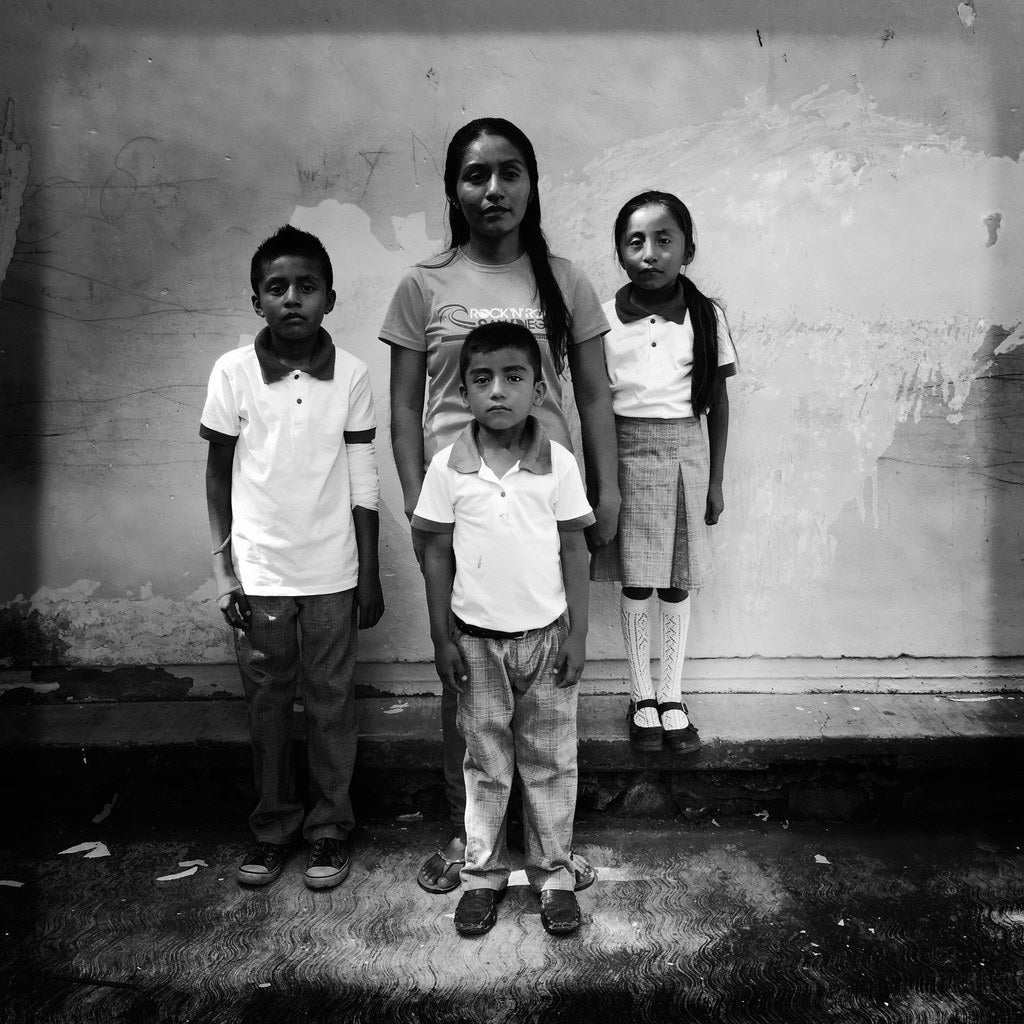

Portraits of families who decided to keep their children at the Año de Hidalgo primary school, where the unionized teachers were banned.

If you want to understand what’s wrong with the education system in Mexico, you only have to look at Elba Esther Gordillo, who for decades was the face of Mexico’s public education and the most powerful woman in the country — and now sits in jail.

Gordillo’s face is striking — her eyebrows shoot up in a deep V and her lips almost always appear frozen in an angry frown. Many in Mexico have compared her, in jest, to Chucky, the antagonist in the horror film Child’s Play.

Gordillo is also known for her voracious appetite for designer clothes and love of real estate: She is believed to have spent more than $2 million at Neiman Marcus, the upscale department store, and she owned several mansions in San Diego, California. According to an investigation by Nexos magazine, she traveled frequently in a private plane that flew nearly 430,000 miles between 2005 and 2013.

As the head of the teachers union, Gordillo ran the country’s public schools and essentially controlled hiring. The union, with its 1.2 million members, is the largest and most powerful in Latin America, and for years held de facto control over the Education Ministry. Gordillo at one point was so powerful that her support of one presidential candidate over another could

determine elections, as she could deliver hundreds of thousands of union

workers' votes.

Meanwhile, the quality of education in Mexico took a hit. In 2012, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development revealed that more than half the students in the public education system could not pass basic competency tests in mathematics.

Shortly after assuming office in 2013, Peña Nieto signed a sweeping education reform into law. It transferred power from the union to the federal government, established periodic evaluations for teachers, instituted workshops for educators, and allocated resources to improve infrastructure, especially in some of the poorest corners of the country.

The reform spurred huge protests, with members of the CNTE attacking local government offices, temporarily closing down the main boulevard in Mexico City, and at one point blocking access to the airport. The teachers “come and talk to us about education, but what education are they talking about when our children turn the TV on and see the disasters they are creating on the street?" said Marisol, a mother and member of the Head of Families Committee in San Miguel del Puerto.

One of the biggest sticking points for CNTE members, many of whom have not taken teaching courses in decades, is the periodic evaluation. They say it puts teachers from impoverished and isolated regions at a disadvantage. Some of the schools in these areas have limited access to electricity, take hours to reach on foot, and cater to indigenous communities who still communicate in their native language.

Supporters of the reform say it was long overdue.

The CNTE “is holding education hostage,” said Lizbeth Rodríguez, a teacher who accuses the group of placing its political interests before children’s education. "It's delinquency," she added.

Rodríguez, who teaches at the original school in San Miguel del Puerto, had just finished college about 15 years ago when her friend, a physical education teacher at a public school in Oaxaca, told her he knew someone who could get her a job. His offer, however, came at a price: She could pay $150,000 pesos or get a discount of $20,000 if she had sex with him, Rodríguez remembers him saying.

“I couldn’t believe how far things had gone,” she said.

What Rodríguez experienced was not uncommon, an employee at the Education Ministry, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he did not want to be identified admitting the embarrassing practice existed, confirmed to BuzzFeed News. Aspiring teachers could for years also rent or inherit their permanent positions at schools around the country. Teachers suspended classes on a whim, often because they wanted to attend protests.

Shortly after lawmakers passed the reform, Gordillo was investigated and jailed on suspicion of embezzlement and tax fraud.

When teachers returned to San Miguel del Puerto after a two-month protest in the winter of 2013, they found the school gates locked and a group of parents huddled at the entrance. The parents, who had warned them to reconsider their strike earlier in the year, started firing flares, a signal to call other parents for backup. Within minutes, dozens of parents came together to physically prevent the teachers from entering the school.

Many parents said they felt more disrespected and disillusioned when the teachers left despite their pleas and warnings. Their children spent more time at home than in classrooms and the parents feared their sons and daughters were falling irreparably behind.

“We’ve seen it with ourselves. I don’t want my daughter to suffer like I have. I want her to better herself,” said Marisol.

Weeks before the teachers returned, Marcial Vázquez, a father of two kids, convinced about 100 angry parents to hire new teacher trainees from nearby communities. They even decided to donate a few dollars a month to pay for the trainees’ food and commute.

Gabriela Canseco, one of the CNTE teachers, was shocked when she returned from the protest. They’d always had control over the town’s schools and students — but not anymore.

“I wanted to pack my bags and go,” Canseco said.

But she decided not to give up. So she set up a school in her living room, where the bright blue walls are now covered with unintelligible pencil marks.

Like evangelists, Vázquez and Canseco started going door to door, trying to convince undecided parents to send their children to their competing schools. Canseco reminded them that the CNTE school was the only officially recognized school in town and, therefore, the only one that offered students certification after they passed.

Vázquez sought out twentysomethings like Santiago to teach at the old school. In a region with few real job opportunities — many of the men here have left for the US and those who stayed behind are subsistence farmers — the offer was tempting.

Meanwhile, people slowly grew accustomed to passing neighbors on the quiet, undulating roads without exchanging a word. In the neighborhoods, they engaged in gossip about whose children had nicer-looking school supplies and which school threw the best end-of-the-year parties.

Soon, parents said children who attended rival schools began bullying each other. Kids who continued attending the original school warned each other not to speak with their friends at the new school.

Parents too felt like they were being pulled in different directions. Monica Mijangos, who sends her three children to the old school, said she felt like “a weird animal” when she went to her godson’s birthday party, where everyone ignored her because they were affiliated with the new school.

Santiago refused Vázquez's offer to teach at the old school. She said she was appalled that he and other parents were willing to replace experienced teachers with unprepared teacher trainees. Parents at the old school have asked the Oaxaca teachers union, which has been more open to the reform than the national CNTE group, to send the town salaried teachers who have passed the evaluation as proposed in the reform.

But none of the parents here, including Santiago, know what exactly the evaluation measures. And like most parents, she remains protective about her decision.

“Everyone,” she said, "is free to do as they please with their kids."