On February 4, 1983, Karen Carpenter died while she was reaching for a fuzzy bathrobe in the bedroom closet at her parents’ midcentury suburban home in Downey, California. By all accounts — Ray Coleman’s 1994 biography chief among them — Karen spent the day before she died cruising between suburban chain stores, looking for sturdy household items, like a washer-dryer at the Downey Gemco, a big-box shop absorbed by Target in the mid-1980s, which she affectionately referred to as “the Gucci of Downey.” She ate a shrimp salad for dinner with her parents at Bob’s Big Boy and picked up a couple of tacos to go from a local joint next door, so she could snack on them while indulging in the made-for-TV spectacle of a manscaped, micro-kimono-clad Richard Chamberlain in Shogun. Everyone thought she was on the mend, the very picture of SoCal suburbanity in repose, eating tacos and watching the tube all night, before what was supposed to be another sunshiny day in an endless season — nay, a lifetime — of sunniness.

On the other side of the Pacific, a mere stone’s throw from the land of Shogun and newfangled devices like sing-along karaoke machines, I learned about Karen Carpenter’s death in the waiting room of a dubious travel agency in Little Ongpin, Manila’s old Chinatown district. I was 9 years old and stuck there with my musician parents. They were making arrangements for our departure from the Philippines, where I was born, to the dry heat of Southern California, where my white stepfather grew up, just 50 miles east of Downey, in a region called the Inland Empire: a place with its own aerospace and defense plants nestled between the citrus groves and stucco, like the one Agnes Carpenter, Karen’s mom, worked in for many years.

Karen Carpenter Dies at 32 screamed the newsprint just above the fold of a Filipino newspaper discarded on the cracked, moist Naugahyde bench next to me. Even though my body had slackened while I was sweating it out in the tropical density of that miserable waiting room, cooled only intermittently by a half-cocked electric fan, my spine went stiff as soon as my eyes grazed that headline. SusMaryosep! I cursed in my head. My namesake is dead. And she died young — at 32, a year younger than Jesus himself.

At 9 going on 10, I was just growing into my fear of mortality, which was aggravated by the fact that we were about to take another epic, transpacific journey on a jet packed with people chain-smoking duty-free Dunhills. At least this was how I remembered my first flight to the States, when I was 5. I also recall the oxygen masks dropping somewhere past Guam, and my mother setting her half-drawn cigarette in the tiny armrest ashtray before strapping a mask over my face.

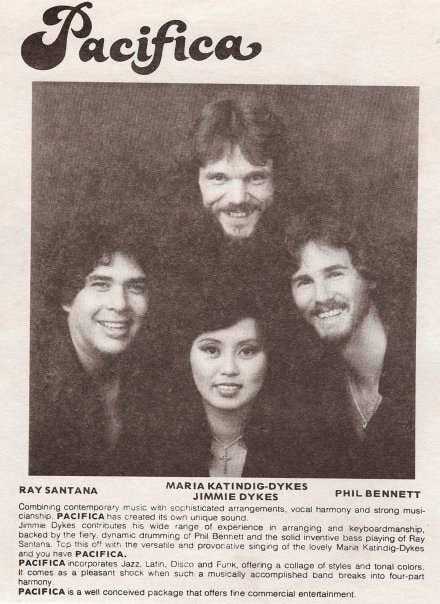

My family, comprising mostly professional musicians, made a lot out of the fact that I was named after Karen Carpenter instead of a relative, saint, or some other Catholic luminary. My grandfather and his brothers — Romy Katindig and the Hi-Chords — were credited with innovating Latin jazz in the Philippines in the 1950s and '60s. My mom, whose stage name is Maria, carried on the family business, briefly singing in OPM — Original Pilipino Music acts — in the 1970s with supergroups like Counterpoint and the Circus Band, before falling in love, and forming a touring jazz combo with my stepfather: a California-born, Hawaii-based musician named Jimmie Dykes. His Pacific Rim roots landed him gigs with the top Filipino performers of the 1970s, including one of my mom’s godfathers, crooner Roberto “Bert” Nievera from the Society of Seven.

My own mother’s voice was often compared to Karen Carpenter’s, when both of them were in their prime, so Karen was like family — but more of a distant relative whose resemblance felt significant even if it was only circumstantial, and whose global accomplishments were touted as an aspiration for my musical clan: Karen Carpenter, superstar.

Even before she died, in 1983, she fulfilled something of a spiritual role in our home in Manila, like the friendly ghosts our neighborhood curandera claimed to have found living in our duhat tree, and with whom my grandmother, Linda Katindig, tried to negotiate one evening after several hours of mah-jongg and too many bottles of San Miguel beer. She asked the mother-daughter spirits not to manifest in front of us, lest they actually scare us to death, even as she acknowledged and respected their own claims to residency and tacitly accepted their ubiquity. Karen, too, was everywhere: in the late-night sing-alongs around the water-damaged upright piano on the veranda, in the cook’s whistled refrains of “Top of the World,” in my name. But most of the time, as the song goes, it was just the radio.

Though there aren’t any charts to prove that the Carpenters were more popular in the Philippines than in any other nation in the world, their enduring presence on Filipino radio and in Filipino-American karaoke repertoires attests to my people’s profound affinity with this most wholesome of American duos. After all, the Carpenters famously performed at Nixon’s White House during West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s state visit, around the same time our neighbors in Southeast Asia were ablaze in napalm and our own would-be dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, was declaring martial law. Their album Now & Then, from 1973, the same year my teen parents (who met performing in a Manila concert production of Jesus Christ Superstar) christened me “Karen,” has been clocked by music critic Tom Smucker as “one of the greatest pop music explorations of whiteness in the last half century.”

The Carpenters’ westward migration from Connecticut to Downey, California, a white, working-class suburb conveniently situated between Orange County and Los Angeles, would seem to affirm this narrow trajectory toward “whiteness and promises,” to invoke a Filipino karaoke machine that misinterpreted the line about “white lace and promises” in “We’ve Only Just Begun.” Both the original lyric and the error are essentially referring to the same thing: an American suburban fantasy of the good life, with a good wife, “sharing horizons that are new to us,” but not foreign or strange in the grander scheme of things. Familiar. Comfortable. Just as things should be — or, at least, as we always pretend we want them to be. As Smucker writes in “Boring and Horrifying Whiteness: Lawrence Welk and the Carpenters,” “Control and precision — often assigned as white musical values — and elaborate pop production that implies a kind of mass affluence, locate the Carpenters’ soft rock in the suburban world abstracted on the Now & Then album cover.”

It was in the master-planned splendor of Downey, and in the Carpenter family home, featured on the 1973 cover of Now & Then, that Karen spent most of her life. She learned how to keep time playing drums at Downey High, with what would become the Carpenters’ characteristic precision. She’d harbored a minor musical crush on a Latino kid in the marching band, Frankie Chavez, and asked him to teach her how to play, after several failed efforts at mastering more ladylike instruments like the flute, the glockenspiel, and the accordion. The notoriously exercise-averse Karen also wanted an excuse to get out of gym class, so drumming ensured she would be indispensable.

Sure, I was Karen, but I also wanted to be — I probably already was — Frankie.

When I first read Ray Coleman’s The Carpenters: The Untold Story, a number of years ago, I slash-fictionalized a more elaborate, amorous relationship between Karen and Frankie, based purely on the line “She admired the drumming of a young Frankie Chavez.” As a recovering SoCal suburban band geek myself, I knew all too well the hormonal frenzy in public-school music practice rooms, especially when drums and drummers were involved. And as a brown butch lesbian named Karen who worked through a whole hell of a lot of gender trouble in the quasi-militarized structure of marching band, with captains for every section (drums, color guard, and the horn line, of which I was the captain), I could identify with both sides of the slash. Sure, I was Karen, but I also wanted to be — I probably already was — Frankie.

In her own way, Karen Carpenter also wanted to be Frankie: She wanted to wield the sticks, to set the beat. In a 1976 radio interview with Charlie Tuna on the newly formed KIIS, Karen explained how it all happened: “In my junior year I got real friendly with a kid named Frankie Chavez, who was head of the drum line… I said, ‘Let me see if I can play. I know I can play.’ I went over, I picked up a pair of sticks. It was the most natural-feeling thing I’ve ever done, and that was it.” Explaining why their relationship never evolved beyond the innocuous status of “good buddies,” despite the fact that Karen may have been “smitten” (in biographer Randy Schmidt’s words), Frankie Chavez observed that Karen “had that little tomboy streak to her and used to talk like a beatnik. I loved that she would talk like a jazz player.” Karen’s musicianship, her adeptness at an instrument, and her ability to talk like a “player” gave her access to the ensembles of largely male musicians that Richard assembled to perform locally shortly after he started attending California State University at Long Beach, which was a mere 12 miles south of Downey, in 1964.

There’s a photograph of Karen on tour with the Carpenters in 1975 wearing a custom-made, iron-on tee with "LEAD SISTER" in block letters across the front. As Richard explained in an online chat with fans, a Japanese magazine mistakenly translated the word singer as “sister” in an interview with the band during their world tour in 1974. Karen thought it was hilarious, and had the T-shirt made the following year to wear for a special drum bit during the middle of their show in which she soloed, marching-band style, on a snare. The largest fan organization dedicated exclusively to Karen is called Lead Sister in honor of the iconic images of her wearing that shirt and rocking her snare. But the joke behind “lead sister” is a cruel one, insofar as it reveals a pointed and painful truth about Karen Carpenter: She was the lead, the star, yet she was defined, both in public and private, by her relationship to her brother.

In 1967, Karen followed her brother to Cal State Long Beach, where he was pursuing his dream of becoming a composer and professional musician. His dream was hers, and like their parents, who had relocated the family across the country to foster Richard’s musical aspirations closer to Hollywood, Karen, too, would continue to pursue the paths carved by Richard’s ambitions.

Long Beach was nicknamed “Iowa by the Sea” in the early 20th century because it offered a sunny sanctuary for throngs of transplanted Midwesterners. Though it was only 20 minutes away from Downey by car, Long Beach was a world away, at least when it came to the Carpenters’ musical and personal development. After playing regularly as the Richard or Dick Carpenter trio in such Hedwigian venues as the Jolly Knight steakhouse in Garden Grove, with Karen on drums and occasionally singing vocals, both Karen and Richard inevitably found themselves more immersed in the musical curriculum on campus, where they joined the university choir directed by Frank Pooler. Long Beach — specifically Cal State Long Beach — is where the “Spectrum sound,” later to be both celebrated and derided as the pristine, obsessively produced Carpenters sound, was cultivated. An important precursor to the Carpenters’ own overdubbed vocal sensorium, their experimental vocal ensemble, Spectrum, performed choral pop with tight harmonies akin to the Beach Boys’, only scored to more elaborate time signatures and jazz syncopations inspired by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which was all the rage in California.

I didn't realize my affinity for the Carpenters was what they used to call "corny" until I landed in the same Southern California suburbs a decade after the Carpenters' heyday.

The band failed to make a dent in the music scene, despite a vigorous show schedule that included hip Hollywood venues like the Troubadour and Whiskey a Go Go. Having downsized once again to a duo with Karen, Richard began to experiment with overdubbing, replicating the harmonically intricate Spectrum sound with their voices alone: think “I Won’t Last a Day Without You,” with its orgy of choral interludes and tight, five-part melismatic riffs and resolutions. This wall of harmony, once a product of the pair’s exogamous experiments with choral collaborators from school and church, winnowed itself to what we now recognize as the Carpenters’ sound: a seemingly insular one, with a sweet layering that owes its richness to what is, in essence, an infinite redoubling of sameness. It is a sameness born of the suburbs, and nurtured in Southern California’s emblematic structures: in its garages, churches, chain family restaurants, and public schools; in the region’s many defense plants; in its vacation mountain getaways; at Cal State Long Beach.

Beyond the surf and sand, it is this Southern California — an interconnected sprawl of suburbs packed with good public schools, venerable places of worship, and reasonably priced themed restaurants with live music from bands like the Dick Carpenter Trio — that seduced so many midcentury dreamers of the golden dream. This is the same fantasy peddled across the Pacific through the Carpenters’ cavalcade of hits, and through Karen’s welcoming voice, in which (like Ella Fitzgerald’s) you could always hear the subtle curve of a smile, even if she was singing about tears.

I didn’t realize my affinity for the Carpenters was what they used to call “corny” until I landed in the same Southern California suburbs a decade after the Carpenters’ heyday, and a month after Karen died, in search of the kind of American prosperity epitomized by a perfectly edged lawn. "Corny" is a word that retains its saliency in its everyday use in the Philippines, even though its usage has diminished in the American vernacular. The fact that I kept using it, if primarily to punish myself for my failed efforts at assimilation by touting my affection for decades-old soft rock, says something about how out of time I truly was when I first landed in the region’s neatly planned subdivisions, where newer meant better.

To be corny is to be “mawkishly old-fashioned: tiresomely simple and sentimental,” and this definition describes my attachment to the Carpenters with searing precision. Even though Karen was supposed to be my gateway to a whole new world (albeit a world obsessed with yesterdays), she actually ended up being the anchor to my old one: to the Philippines, where corny still means something. And even if the Carpenters were the whitest of musical acts, engineered in the most white-bread of contexts, nothing felt more Filipino to me in those first lonely months fresh off the boat than the sound of Karen’s voice.

In 2007, I had my first balikbayan, or “homecoming” journey, to Manila as a grown-up without parental chaperones. Balikbayan translates literally as “return to country,” but refers in a more spiritual and colloquial sense to homecoming, to the many Filipinos living permanently abroad who return to the country and who implicitly always have a country to return to. In preparation for this momentous trip, I leafed through the most current Lonely Planet guide at a Borders bookstore in the Riverside Plaza after having lunch with my dad. This is what I learned about my people, at least as they are viewed through the eyes of a plucky travel writer: “Despite years of injustice at the hands of colonial and homegrown rulers, and despite being for the most part dirt poor, Filipinos are the happiest people in Asia. This incongruous joie de vivre is perhaps best symbolized by that quirkiest of national icons, the jeepney. Splashed with colour, laden with religious icons and festooned with sanguine scriblings, the jeepney openly flaunts the fact that, at heart, it’s a dilapidated, smoke-belching pile of scrap metal. Like the jeepney, poor Filipinos face their often dim prospects in life with a laugh and a wink.”

It struck me then that even though this Lonely Planet writer observed the cultural incongruity of Filipinos’ poverty and joy in a somewhat flippant manner, they managed to stumble upon a truth, one that revealed to me how this alleged Filipino orientation toward joy amid despair could be seen as a negative for the picture perfection modeled by the Carpenters, for their profound despair underlying an intense sunniness.

While wallowing in my sentimental journey in Manila, I was awash in the music scored by the collective DJs of everyday life in the Philippines: the taxi and jeepney drivers blasting their radios; the Palawan Idol winner singing Extreme’s “More than Words” and Jobim classics between shifts tending a beach bar; the Manila municipal government’s swanky sound systems piping soothing soft rock into Rizal Park, the city’s monument to the slain national hero José Rizal. I heard the Carpenters everywhere. I heard “Sing” on the radio at Baclaran Market, “We’ve Only Just Begun” performed by a cover band in Malate, “Close to You” strummed on the guitar in the resort town of Boracay. In each instance, almost everyone present sang or hummed along, some under their breath, others with full-throated abandon. At the time, I thought perhaps it was all part of the buildup for Richard Carpenter’s scheduled visit to the Philippines a few months later. My subsequent visits have assured me, though, that this was — and still remains — an everyday occurrence. On Valentine’s Day in 2008, Richard Carpenter was enlisted to serenade the sitting Philippine president, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, at Malacañang Palace, the state residence. Though Arroyo and her cronies were mired in scandal and corruption, the national paper, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, reported that “Singing with Carpenter ‘saves the day’ for Arroyo,” and noted that Arroyo “broke into song with lyrics evocative of the tumult besetting her administration.” Arroyo sang a ballad, “I Have You,” from one the Carpenters’ lesser-known albums composed mostly of covers.

To this day, the Carpenters hold the distinction of being among the few American acts to boast Philippines-only radio hits.

Also performing with Richard during his visit to the capital was Claire de la Fuente, one of several artists since the 1970s who share the distinction of being dubbed by the press (and, in this case, de la Fuente's own publicists) “the Karen Carpenter of the Philippines.” De la Fuente earned this title, as her Wikipedia page explains, because “her voice has a striking resemblance to that of the late singer.”

During his visit to Manila in 2008, Richard invited de la Fuente to record a song he originally composed for Karen to sing before she passed away, “Something in Your Eyes,” which was first featured on his 1987 solo album, Time, with Dusty Springfield filling in the vocal track Karen never got to record. De la Fuente’s version, which is actually a cover of what is already an ersatz rendition of a song whose original voice disappeared, amalgamates both Karen’s and Dusty’s vocal styles. With a slight Tagalog accent, de la Fuente evokes Dusty’s late-’80s-era wear-and-tear with her unintentional rasp, while her phrasing shadows the way Karen scooped her notes down from the melodic sweet spots to sit hard on the lower tones of her register with that signature wide vibrato. Despite a lot of hullabaloo in the Filipino press about Richard Carpenter and Claire de la Fuente’s collaboration, her version of “Something in Your Eyes,” and her album, which bore the same title, failed to turn de la Fuente into an “international singing sensation,” as several news outlets had hyperbolically predicted.

To this day, the Carpenters hold the distinction of being among the few American acts to boast Philippines-only radio hits: album tracks largely unknown in other parts of the world but in heavy rotation on Filipino radio, thus elevating these lesser cuts to the prime status of the artists’ more recognizable global hits. As Glenn Tuazon explains in the Manila Review, “never released as a single and apparently deemed a throwaway album cut from A Kind of Hush, [the Carpenters’ ‘You’] reaped a different level of popularity in the Philippines, due to its heavy radio airplay… The song is often the lead track in locally-produced Carpenters compilations, which is strange, considering the Carpenters and their label never considered ‘You’ among the band’s best or most important songs.”

The Carpenters’ “You,” not to be confused with “I Have You,” the song Arroyo sang with Richard in 2008, also happens to be the deep cut that turned Anna Gusmo, an impoverished, blind Manila busker, into a viral-video sensation and an international celebrity during the summer of 2013. Like scores of other Filipinos who gained transnational fame on YouTube — from the Cebu Provincial Rehabilitation and Detention Center inmates who reenacted the Michael Jackson oeuvre to Arnel Pineda, the lead singer for Journey, whom Neal Schon found online after several failed efforts at finding another post-Perry singer for the band — Gusmo, too, was “discovered” on the platform, though her story makes apparent some of the true limits of this road to fame.

Gusmo, along with her husband, Nante, who is also blind, and several other relatives, performs daily at the Pasig Public Market in Manila to earn tips to live on, as well as to collect “donations for the blind.” In February of that year, a shopper named Angel Siawingco captured cell-phone video footage of Gusmo singing “You.” It was later posted on YouTube with the caption “Karen Carpenter You Sung by Blind Woman.”

Siawingco’s grainy video shows Gusmo singing “You” with an uncanny, Karen-esque timbre and tone, while sitting in a plastic chair, rocking a toddler with one hand and holding her mic in the other. Soon all the major Filipino news agencies picked up Gusmo’s remarkable story and propagated her fame, not only nationwide but throughout the Filipino diaspora on international cable networks like TFC (The Filipino Channel). Gusmo and her family continued to earn their living through busking, even as her fame and the number of YouTube views of her marketplace performances grew exponentially. When, amid all the attention, Gusmo was diagnosed with breast cancer, she began seeking donations for her treatment, while several clubs and other entertainment establishments booked her and her all-blind musical ensemble to perform Carpenters covers at fundraisers arranged partly for her benefit.

In 2014, Anna Gusmo usurped Claire de la Fuente as “the Karen Carpenter of the Philippines,” as a simple Google search attests, though her financial circumstances remained largely unchanged. Most of the buzz about Karen’s voice and who truly keeps it alive, not only in the Philippines but throughout the Filipino diaspora, is focused on Gusmo, her rendition of “You,” and the melodramatic narration of her blindness. Ironically, “You” is a song about one’s total absorption in another’s gaze as well as voice: “Sometimes if I look past you / There’s no one beyond your eyes.”

While the Carpenters mania that seems to exist in perpetuity in the Philippines might easily (and to a certain extent rightfully) be construed as yet another of the many vestiges of the nation’s colonial entanglements with the United States — what the scholar Vicente Rafael describes in White Love and Other Events in Filipino History (2000) — I want to make a case here for a power relation more difficult to parse: a different dynamic, another species of intimacy. You see, the Carpenters belong to us, not the other way around. Karen’s voice is not simply a fetish object of self-annihilating perfection, as the scholar Eric Lott has provocatively argued, nor is it the wet, maternal kiss oozing with eros and comfort, as musicologist Mitchell Morris describes it. Neither is Karen just another martyr in the sacred and secular cosmologies of Filipino Catholicism. Journalists who’ve tried to crack the case of why certain “ethnic” communities “worship” seemingly incongruous white singers — i.e., the throngs of Latinos in the United States who are bonkers for Morrissey — have pulled the Catholic card before, implying a one-to-one correspondence between these religious forms of idolatry, sentimentality, and fandom.

But with Karen Carpenter, we aren’t just fans, followers, or cheerful colonial acolytes, Taft’s infamous “little brown brothers” worshipping another white woman’s prudish perfection. Karen’s voice is our voice, and as de la Fuente, Gusmo, and countless others after them will confirm, we have the power to reanimate her, for better or worse, as our echo.

When I am back in Manila and my ears are filled with what I’ve come to understand as my immigrant love songs, written and performed by American pop stars like the Carpenters, this obfuscation of origins scrambles my relationship to space and source. And it is in that headspace of defamiliarization, where one arrives at a clearer sense of the stoniness of the stone — or in this instance, the placeness of a place — that I begin to understand what Karen has actually done for me. She is more than my namesake; she is my constant. She is the anchor to a now, a then, a never-was, and a never-will-be. Karen Carpenter’s dispassionately passionate vocals multiply not only across the harmonies in her own recordings but also through countless Filipino voices, making sense of both Manila and the Southern California suburbs that became my eventual home. Through Karen Carpenter, I came to understand that soft rock might not signal a weakness or vulnerability but rather a strength: the audacity to sound out of place and out of time, like someone who isn’t made for a certain world. Someone who is corny, not simply someone who’s old-fashioned or stubbornly clinging to the notion that “every sha-la-la-la, every whoa-oh-whoa-oh still shines.” Karen Carpenter, the contradiction, helped launch the most soothing of musical oxymorons, soft rock.

Soft rock became the musical genre that turned on our heartlights across the Pacific. Before there was a 710 freeway to slice across Long Beach, grazing El Sereno along the way, Karen created the spark that would inevitably ignite the world with innumerable butane flames.

After listening to Karen Carpenter again, and to the many women who have held the title “the Karen Carpenter of the Philippines,” I begin to hear my mother’s voice anew. It no longer sounds like Karen Carpenter’s, since she abandoned her pop ambitions to become a “real musician.” She chose to labor under the tyranny of jazz, a pursuit for the musically righteous, not for wage vocalists (as she was forced to become when we first landed in Southern California). Jazz was a dominion ruled by men like my grandfather and his brothers, who played like angels but disappeared like devils. Though she capitulated to the family business, my mother still managed to defy their legacy by naming me after the girl singer who also happened to be a girl drummer. A girl who left this world too soon, but who was destined to live forever. ●

Karen Tongson is associate professor of English and Gender Studies at University of Southern California, and the author of Relocations: Queer Suburban Imaginaries (NYU Press). She has a forthcoming book with ForEdge Press, Why Karen Carpenter Matters, and has two books in progress: Normal Television: Critical Essays on Queer Spectatorship after the "New Normalcy," and Empty Orchestra: Karaoke in Our Time. You can also hear Karen talk about pop culture, the arts, and entertainment on the weekly podcast Pop Rocket, hosted by Guy Branum.