Last year, Twitter announced the Innovator's Patent Agreement. In a blog post, the company explained that the IPA is a "commitment from Twitter to our employees that patents can only be used for defensive purposes," and that "[Twitter] will not use the patents from employees' inventions in offensive litigation without their permission." The IPA was introduced in an atmosphere of intense patent trolling; as a public relations move, it implied that Twitter wouldn't use any of its broad patents, such as the one it holds on pull-to-refresh, in a troll-y way.

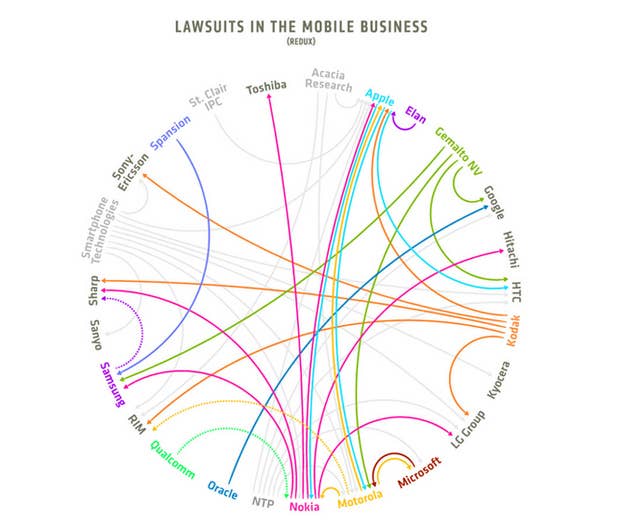

But in a longer-term sense it positioned Twitter as an innocent party — perhaps a victim — in a much larger patent war. The tech giants, including Apple, Microsoft and Google, have been hoarding patents for years. It's defensive, certainly, and can also result in real revenue; Microsoft notoriously makes money from Android handset sales. But patent-hoarding of any kind is unmistakably offensive. It's as if there's a looming, grand-scale patent war, and tech companies are terrified of it.

Today, Google announced a much narrower pledge: to allow open source software developers to use a limited set of patents without fear of litigation. But the language of the agreement, much more so than Twitter's, is treaty-like:

Today, we're taking another step towards that goal by announcing the Open Patent Non-Assertion (OPN) Pledge: we pledge not to sue any user, distributor or developer of open-source software on specified patents, unless first attacked.

"Unless attacked first" is not language we're used to hearing from our tech companies; rather than patents and open source software licenses, it evokes declarations, war, and international accords. Specifically, it recalls what are known as "no first use" agreements, which were put forth by the Soviet Union (which eventually rescinded) during the Cold War, and more recently by China and India — reminders of mutually assured destruction presented as assurances. And, unlike this new breed of patent agreements, they've been debated for years.

Perhaps Google, Twitter, Microsoft and Apple could find strategic value in some of the writing on the first wave of UAF agreements. This article, written by Bernard Feld, one of the collaborators on the first atomic bomb, and published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in 1967, is surprisingly relevant: